Complex Original

There’s no debating the fact that Kendrick Lamar has put together an incredible discography. In fact, it’s so strong it makes ranking his projects even more difficult than it would be for an equally great artist whose career has more obvious peaks and valleys. Who can say, truly, how much better the contemporary coming-of-age movie Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City is against the less replayable but deliciously complex To Pimp a Butterfly? DAMN won a Pulitzer, but is it his best album? How high is too high for Untitled Unmastered, an EP of leftovers that is, in many ways, just as nourishing as some full-lengths? And where is it appropriate to rank an album like his latest, Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers, considering the project’s intentionally raw, imperfect nature. These are challenging questions. Kendrick Lamar makes challenging projects. We did our best to do right by his catalog. These are Kendrick Lamar’s albums, ranked from worst to best.

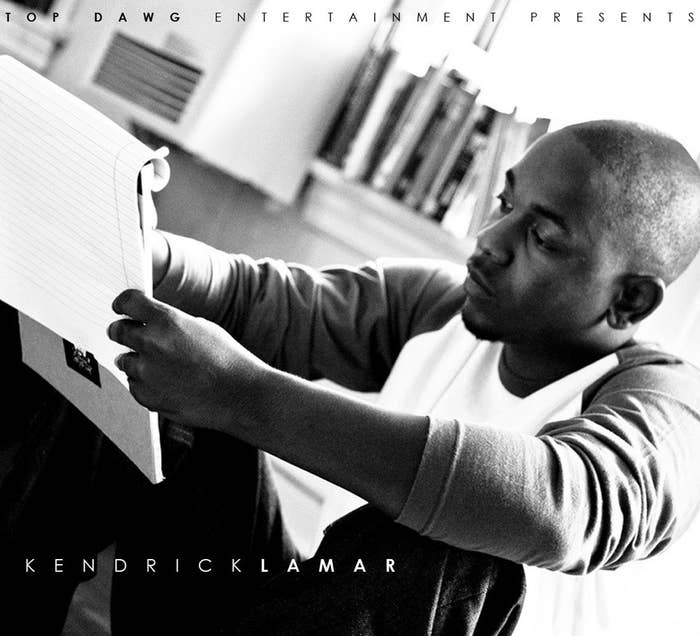

8. 'The Kendrick Lamar EP' (2009)

Label: TDE

Producers: Sounwave, Black Milk, the Foreign Exchange, Insomnia, Jake One, King Blue, Pete Rahk, Q-Tip, Wyldfyer

Features: Angela McCluskey, Ab-Soul, JaVonté, Jay Rock, BJ the Chicago Kid, Punch, Schoolboy Q, Big Pooh, Ash Riser

Kendrick's debut release (minus a handful of bootlegged, though easy to find collections of juvenalia) is a fascinating listen that will likely only grow more intriguing as the years go by. He's looking for stardom, acclaim, money, and bright lights—"Grammy" is one of the project's most frequently-mentioned words, and Donald Trump's name comes up more than once as aspirational shorthand.

But even more than success, Kendrick is determined even this early on to show us who he is. What makes the project resonate today as more than a promising debut is that who Kendrick is has in many ways remained consistent. The record introduces characters and themes that he would revisit, especially on Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City: his parents, the death of his Uncle Tony at the Louis Burger, the devastation the crack era wreaked on his neighborhood and his family, his struggle with religion, and even the phrase "good kid, mad city" itself, which shows up repeatedly on the record like a promise of things to come.

Artistically, Kendrick is a very good young rapper, sometimes bordering on great. He doesn't have the crazy voices yet, or the command of rhythm and song structure that would begin to appear on Section.80 (or even Overly Dedicated). His ambition just barely outstrips his ability, as you can hear most clearly on "Vanity Slaves," where his attempts at fast rapping are thisclose to working, but not quite there. Another marker of youth is the occasional cringe-worthy punchline, like "Draped in some fly shit, call me Jeff Goldblum."

But overall, the EP (an intentional misnomer, as it's 15 tracks) is worthwhile for the glimpse it gives into the mind of an artist who would quickly grow to into arguably the most important of his generation. The record's final track (save a bonus cut) concludes with voices asking Kendrick, "Who are you? What are you trying to say? What are you trying to accomplish?" Those questions are even more interesting—and even more important, for him and for us—now than they were in 2009. The Kendrick Lamar EP is historic for being the rapper's first real attempt at providing answers. —Shawn Setaro

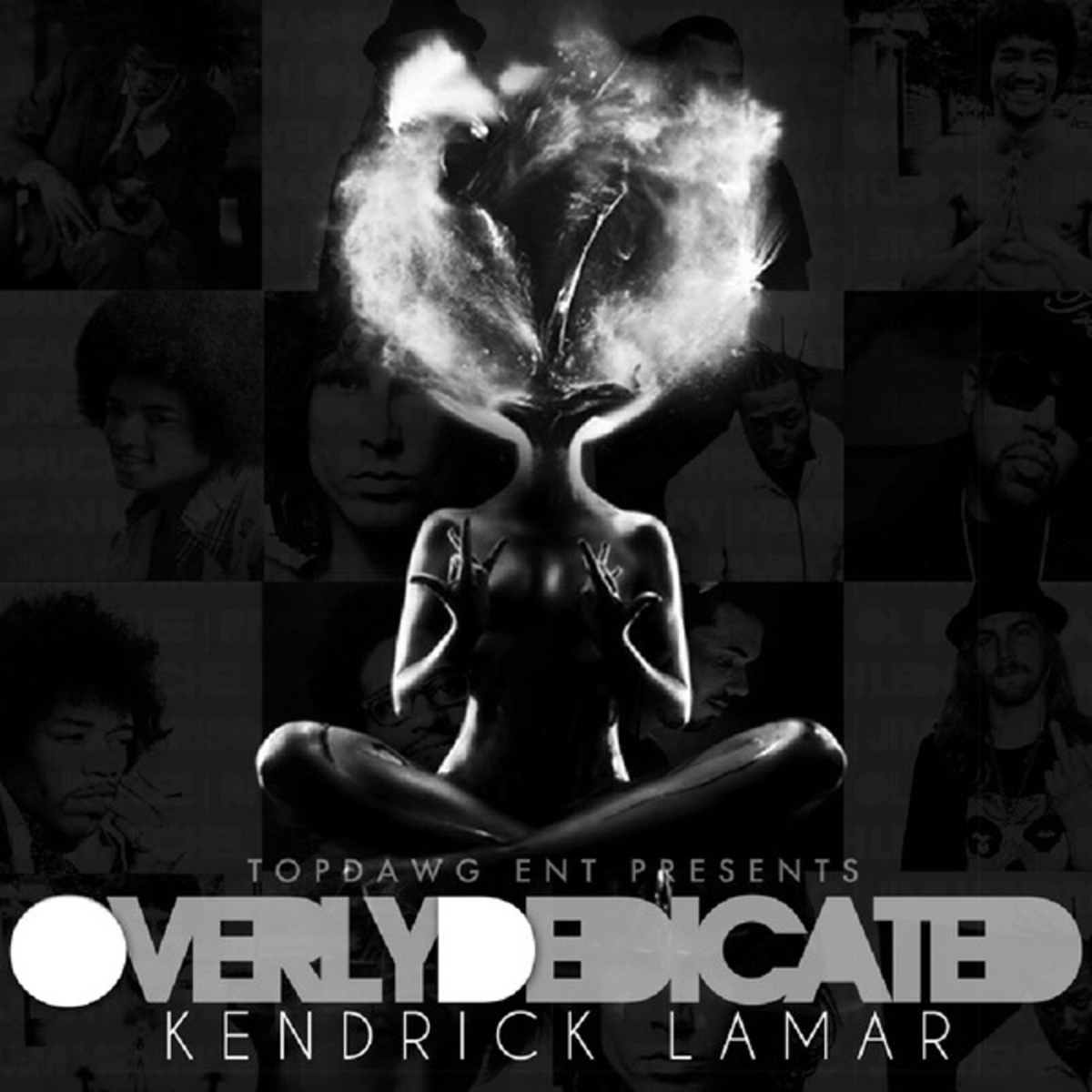

7. 'Overly Dedicated' (2010)

Label: TDE

Producers: Jairus "J-Mo" Mozee, King Blue, Drop Beatz, Sounwave, Tae Beast, Tommy Black, Willie B, Wyldfyer

Features: Jhené Aiko, Ab-Soul, JaVonté, Schoolboy Q, BJ the Chicago Kid, Ash Riser, Alori Joh

Jim Morrison, peeking out in his pale-faced, statuesque glory, is on the cover of Kendrick Lamar’s first retail release, Overly Dedicated. It’s ridiculous. But perhaps appropriate for a 23 year old still figuring out what he does well, how clever is too clever, why subtlety oftentimes sounds smarter, and which influences are best left on the bedroom wall. That fallen icon of downtown cool, Dash Snow, opens the tape, speaking about his dependency on big bottles of water, Marlboro Reds, and music—music most importantly. (Of course, another of Snow’s dependencies—heroin—killed him in a luxe East Village hotel at the age of 27.)

Even though the opening is poignant, and Snow’s voice sounds great against a sample of the Roots’ “A Peace of Light,” the New York artist makes about as much sense as Morrison in terms of framing Kendrick Lamar’s overall artistic project as we understand it today. Growing up is much about winnowing away as it is accumulation, and from the vantage of 2017 it’s best that Kendrick left behind his fondness for gimmicky acronyms (even though “R.O.T.C.” is a very good song) and extraterrestrial romance metaphors (even though “Alien Girl” has one of the catchiest hooks here).

What he’s saved: a seriousness of purpose that, thankfully, he’s grown into, a love of language that scatters chestnuts in every song, if not verse, and a total lack of self-consciousness for how weird his voice can be. On “The Heart Pt. 2” he sounds exasperated and upset, like a frantic Eminem (he hasn’t let go of that influence, either—listen to “Feel,” from Damn). He loves Wayne, too, and borrows from his “Swag Surf” on “Michael Jordan.” He’s a young fan on the verge of understanding his powers, but unlike the sorcerer's apprentice he’s in control. That out-of-breath delivery sounds purposeful, a formal decision. The title explains that he’s dedicated, suggesting practice. Dedicated, suggesting effort. Dedicated, suggesting craftsmanship. At 23, his art is not instinctual. Even now, when he boasts about the cosmic coincidence that permitted his skills to flourish, there’s no mistaking that he’s the best because he decided to be that way, and then worked at it. —Ross Scarano

6. 'Untitled Unmastered' (2016)

Label: TDE, Aftermath, Interscope

Producers: Astronote, Cardo, Egypt, Frank Dukes, Kendrick Lamar, Terrace Martin, Mono/Poly, Ali Shaheed Muhammad, Ritz Reynolds, Sounwave, Thundercat, Adrian Younge, Yung Exclusive

Features: Jay Rock, Bilal, SZA, Anna Wise, Cee-Lo, Egypt, Thundercat, and Punch

Untitled Unmastered is a collection of ephemera from the To Pimp a Butterfly sessions. He performed some of these verses on late-night television and at the Grammys, and allegedly LeBron James' Twitter urging convinced TDE's Top Dawg to share these songs with the world. Even as sketches, these untitled songs contain more power and demonstrate greater technical ability than any of his peers could easily muster.

In a year where K-Dot showed out with guest verses on blockbuster albums—Lemonade, The Life of Pablo, Starboy, Blonde—he left his most impactful performances for Untitled Unmastered, a project that furthered the rich sound of To Pimp a Butterfly while leaving behind the conceptual storytelling like a discarded chrysalis. The project is, in some ways, better for the lower stakes.

By removing the larger framework, Kendrick can take detours. For instance, the opening verse of "Untitled 05" is one of his most intense bouts of storytelling to date, describing a would-be killer pushed to the edge by an unjust world. "See I'm livin with anxiety, duckin the sobriety/Fuckin up the system I ain't fuckin with society/Justice ain't free, therefore justice ain't me/So I justify his name on obituary." His flow on that song is hard-nosed and each line lands with the dry smack of a hand slapping a domino down on a card table on an airless day. It's just one of many insanely good pockets on a project that doesn't really need to exist. —Edwin Ortiz

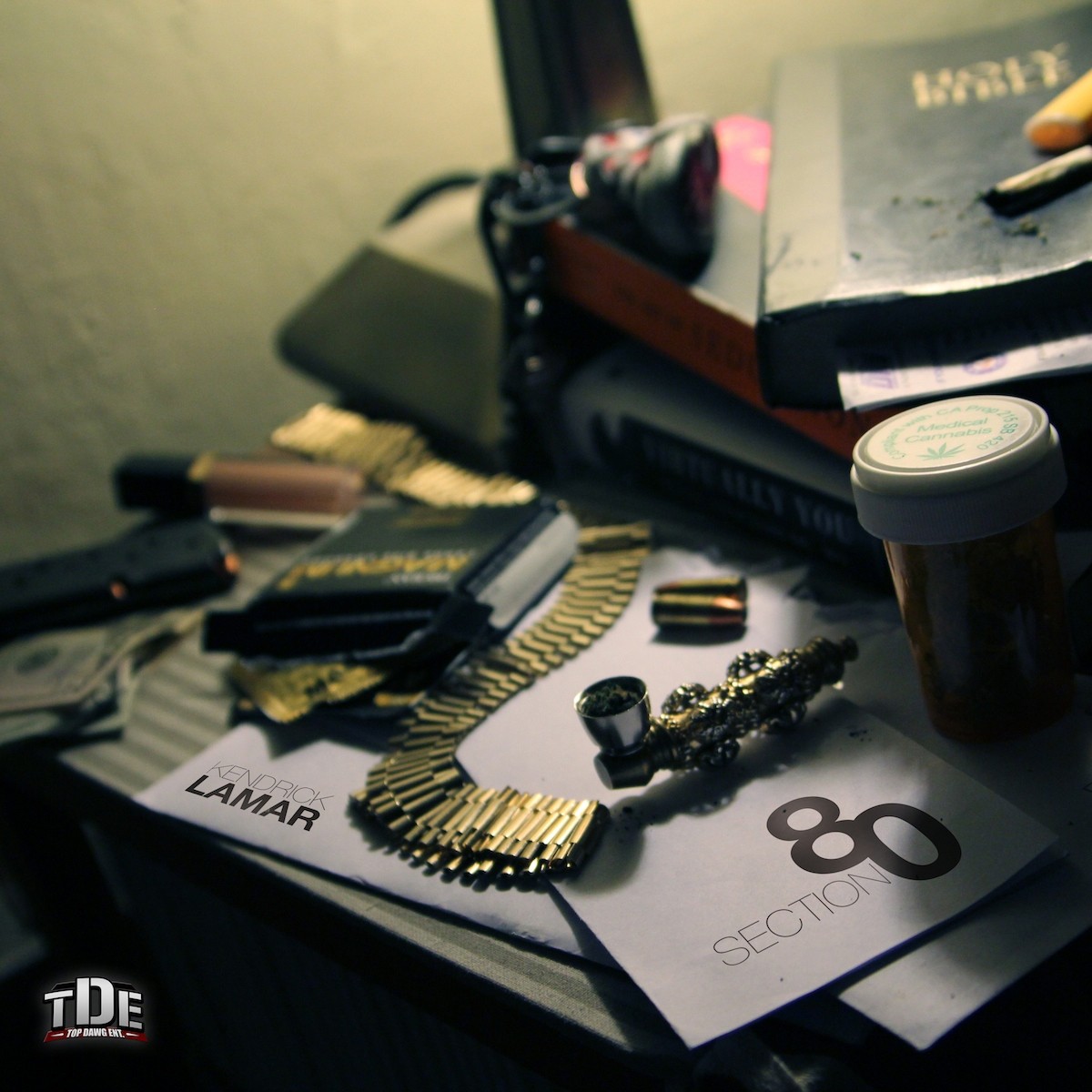

5. 'Section.80' (2011)

Label: TDE

Producers: Iman Omari, Dave Free, J. Cole, Sounwave, Tommy Black, Tae Beast, Terrace Martin, THC, Wyldfyer, Willie B

Features: Colin Munroe, GLC, Schoolboy Q, Ashtrobot, BJ the Chicago Kid, Ab-Soul

Was there ever a doubt that Kendrick was going to become one of the greats—and quickly—after hearing this album? At 24, Kendrick Lamar dropped an album that wasn't a straightforward classic, but for those that hadn't heard Overly Dedicated, Section.80 was likely the most assured introduction to an artist this side of The College Dropout.

The sound of Section.80 is, overwhelmingly, the sound of a young man in love with the possibilities of his voice and language. Despite the diffuse ambition to make Section.80 a definitive megaphone for the crack generation, it's a remarkably light, thrilling listen. It can be a weirdly soothing experience, watching someone do what they're meant to; listening to Kendrick rap on "Rigamortus" is like watching a bird fly.

Of course, he still had room to improve. In his quest to make an album of importance, though, Kendrick weighed Section.80 down with one-sided morality plays, like “Keisha’s Song.” But each is told deftly enough to escape the trap of heavy-handedness that dooms most rappers this focused on enacting social good through their music. That, coupled with the empathy Kendrick has always worn on his sleeve, more than makes up for the weaker moments on Section.80.

Stylistically restless, relentlessly knotty yet still inviting, Section.80 is an album filled with good rapping, idiosyncratic detail, and the feeling that you're privy to one man's entire mind. It's also the album on which Kendrick learned how to make an album. Its threads are the blueprints for what he would eventually go on to achieve—three classics, and counting. —Brendan Klinkenberg

4. 'Mr Morale & The Big Steppers' (2022)

Label: TDE, Aftermath, Interscope, pgLang

Producers: The Alchemist, Baby Keem, Beach Noise, Bekon, Boi-1da, Cardo, Craig Balmoris, DJ Dahi, DJ Khalil, The Donuts, Duval Timothy, Frano, Grandmaster Vic, Jahaan Sweet, J. Lbs, Oklama, Pharrell Williams, Sounwave, Tae Beast

Features: Baby Keem, Kodak Black, Blxst, Sampha, Taylour Page, Ghostface Killah, Summer Walker, Amanda Reifer, Sam Dew, Tanna Leone, Ben Gibbons

Kendrick Lamar says that one of his favorite lines on Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers is “real nigga need no therapy” on “Father Time,” explaining that he likes it so much “because that’s how niggas really feel.” This sentiment encapsulates the stigmas that he spends the rest of the album combatting, sheathing his ego in order to address childhood trauma, unhealthy vices, and demons that have plagued the Duckworth lineage for generations. Mr. Morale not only tackles the inner turmoil Kendrick has been wrestling with for his entire life, but also the stigmas surrounding mental health treatment that many in the Black community face to this day.

The statement is a reflection of the Black male experience and an ideology that has allowed generational traumas to persist. Healing is not linear, though, and Mr. Morale reflects the cluttered, kaleidoscopic nature of unearthing deeply buried memories. Throughout the double-sided album, Kendrick puts his therapy notes to wax as he illustrates how pivotal experiences in his life have made him the man he is today. Throughout the album, we hear the clicking and clacking of oxford shoes in the background, representing Dot “tap dancing” around subjects that are still difficult to address. The first side of Mr. Morale finds Kendrick grappling with his newfound realizations using high-energy sounds apparent in songs like “N95” and “Rich Spirit.” In contrast, the second half has a slower tempo that mirrors the sobering stupor of accepting how trauma has affected him.

Mr. Morale illuminates the difficult sides of mental health recovery, as well. On songs like “We Cry Together” featuring Taylour Paige, we hear an aggressive and toxic conversation between two partners. And a song like “Auntie Diaries” demonstrates the pitfalls of growing out of negative learned behaviors, with Kendrick unfortunately using homophobic slurs when discussing the hardships that his transgender aunt faced in their family when he was growing up. Kendrick is still learning on Mr. Morale, which is a pillar to embracing therapy in general. He finally reaches his breakthrough on the album’s penultimate track, “Mother I Sober,” a cathartic journey that analyzes how his mother’s past abuse made her distrust their family and explores the ways that trauma was passed down to him as well.

Kendrick Lamar has spent most of his career making sense of the world in relation to himself, and his most acclaimed work is guided by tales of the streets that raised him, the systems that have exploited our people, and how to break free from them, but the power in Mr. Morale lies in how inward-gazing it is, working as a guidebook to help other people reevaluate the stigmas they have around mental health and begin their own journeys of self-reflection. The songs flow like streams of consciousness, backed by impressive production that help tell Kendrick’s story in a way that’s captivating both lyrically and sonically. Revisiting it in full is somewhat challenging because it’s often difficult to listen to someone be so honest with themself about relatable issues, but that’s what makes an album like this so important. Above all else, Kendrick demonstrates on Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers that trauma takes time to overcome, and that there is no age limit to healing. —Jordan Rose

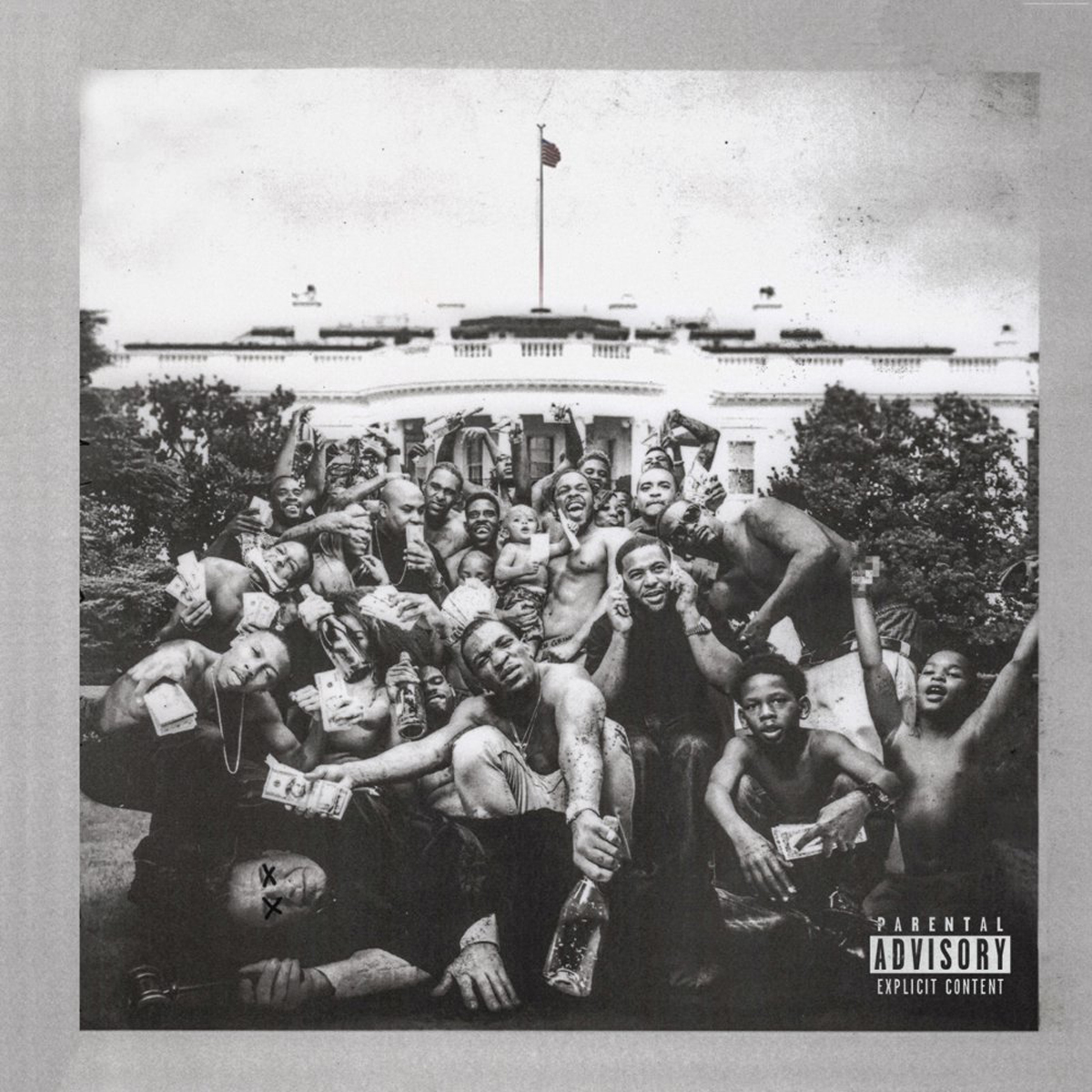

3. 'To Pimp a Butterfly' (2015)

Label: TDE, Aftermath, Interscope

Producers: The Antydote, Boi-1da, Flying Lotus, Flippa, KOZ, Knxwledge, Larrance Dopson, LoveDragon, Pharrell Williams, Rahki, Sounwave, Tommy Black, Terrace Martin, Tae Beast, Taz Arnold, Thundercat, Whoarei

Features: George Clinton, Thundercat, Bilal, Anna Wise, Snoop Dogg, James Fauntleroy, Ronald Isley, Rapsody

If Section.80 and Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City established Kendrick as a technician and storyteller, To Pimp a Butterfly reinvented him as a conduit. Much of the fanfare for the album centered around how unabashedly black it was, but the true thrust of the record is how nimbly it articulates that blackness. Diaspora is traditionally defined in terms of shared geographic origins, but Kendrick portrays blackness as a shared experience—of pain, of joy, of rage, of will. Forcefully he springs back and forth through time and space, connecting Wesley Snipes to Kunta Kinte to Tupac to Nelson Mandela to Kendrick himself. The rhythms of funk, the audacity of rap, the pain of soul, the ecstasy of gospel, and even the theatrics of spoken word propel this journey, and it’s a marvel how effortlessly these traditions fit together. Hip-hop has been an omni-archive of blackness since Bronx DJs first pilfered their parents’ record collections, but few artists have brought that archive to life as vividly as Kendrick. To Pimp a Butterfly doesn't just invoke blackness, it feels it, giving it texture, temperature, and depth.

There's a staggering amount of voices on this record and Kendrick singularly channels them all, slurring, tweaking, bending, and twisting his own voice to find the precise timbre for every speaker. The record falters when Kendrick’s one-man show feels like exactly that (black women are mostly just vessels for his enemy Lucy, for instance), and the butterfly metaphor is nonsensical and convoluted. (Caterpillars pimp butterflies out of jealousy, thus depriving themselves and butterflies of freedom? Wut?) But these blemishes feel like limits more than failures. At its best this record is a nuanced rebuke of the post-racial fantasy inaugurated alongside the nation’s first black president. Kendrick uses blackness as a sword and shield, dismantling the false promises of the American dream and building a cautious hope from the black lives that somehow endure the dream’s deception. The record is an unwieldy blob, but isn't that the story of blackness? —Stephen Kearse

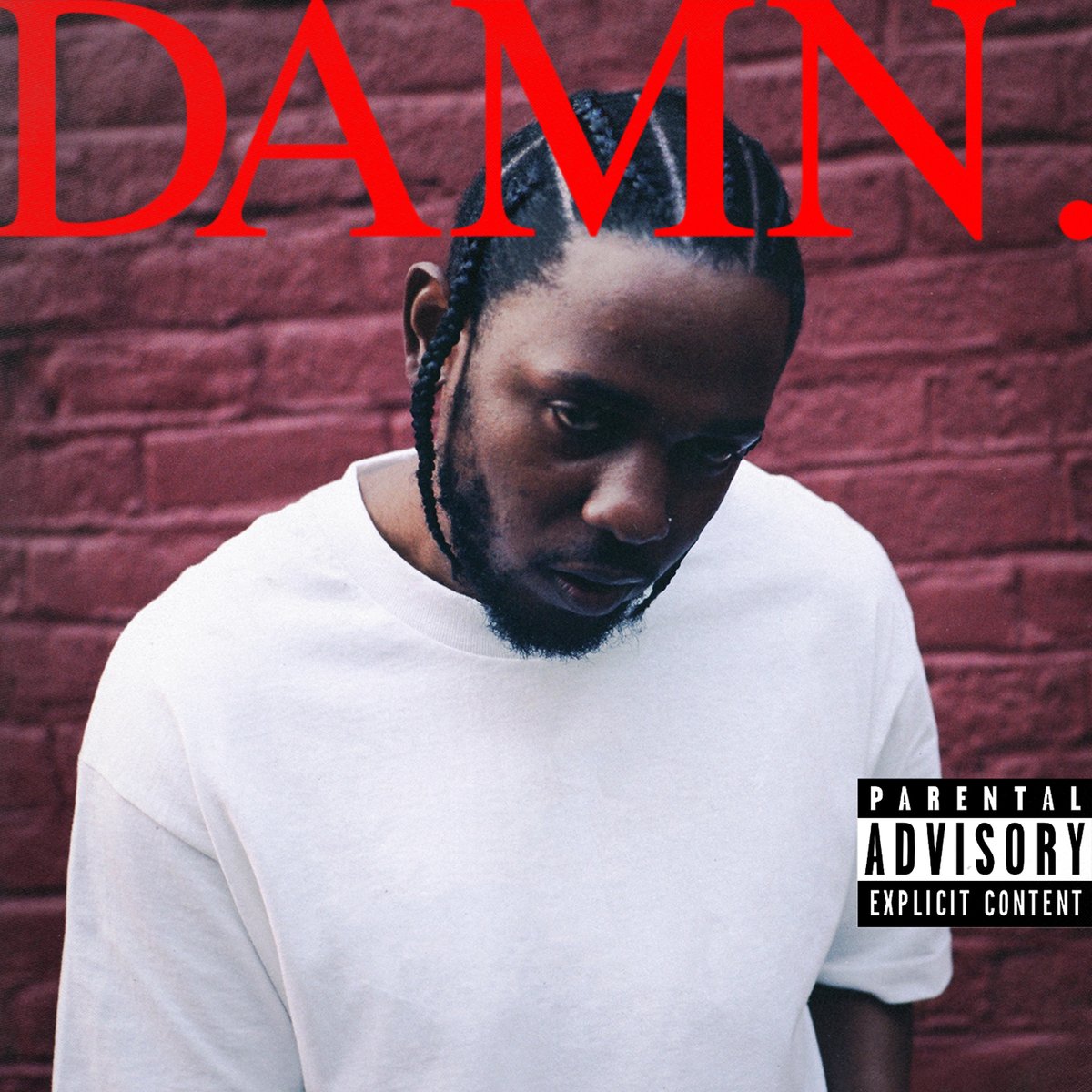

2. 'DAMN' (2017)

Label: TDE, Aftermath, Interscope

Producers: 9th Wonder, The Alchemist, Bēkon, BadBadNotGood, Cardo, DJ Dahi, Greg Kurstin, James Blake, Kuk Harrell, Mike Will Made-It, Mike Hector, Ricci Riera, Sounwave, Steve Lacy, Terrace Martin, Tae Beast, Teddy Walton, Yung Exclusive

Features: Rihanna, Zacari, U2

While peers such as Eminem and Nicki Minaj maintain a cadre of alter egos, Kendrick has always preferred to dabble with the messier and more infinite range of voice itself. He often flirts with the absence of his vocal signature, obscuring then finding again that distinct pinching pitch audiences associate with K-Dot. Though not unnoticed (“rapducer” Crank Lucas’ made a popular video poking fun at this), it’s a feature of his work often muffled in discussions about Kendrick’s place in the rapper matrix and the “conscious” rapper label (that he, admittedly, invites). Perhaps it is harder to have faith in a spiritual leader known to inhabit multiple perspectives at once. Seems only right then that Damn, his most vocally multitudinous project yet, also completely destabilizes any former notions of Kendrick the Prophet. Amen.

With an artist like Kendrick, the gulf between best and “worst” looks razor thin. Though perhaps not a dramatic departure in style, tone, or method, Damn distinguishes itself as the apex of a career-long experiment with vocal elasticity. If an MC’s voice—singular—is his bread and butter, Damn undermines the expectation that rappers be coherent, whole, and recognizable at all times. Damn undermines the expectation that we ourselves be coherent, whole, and recognizable. In a moment where people must be brands, Damn places relentless pressure on the idea that anyone can really get a handle on all the personas that reside within a single person. The album’s questions—formal and implicit—plumb the vocal intertexts that guide our lives: Who am I today? How many me’s do I try on to find the right one? Which version of myself will you love? Which one can I live with? Why do I sound like my mama? Why'm I still telling that tired old story? Who the fuck prayin’ for me?

Songs like "DNA," "Feel," "Pride," and "Fear" bring such self-interrogation to life in lyric. Meanwhile, across the album, contradictory evocations of themes like humility (“I can’t fake humble just cause your ass is insecure” vs. “pride’s gonna be the death of you and me”) and religion (earthly delights vs. heavenly delights) similarly create a sense of uncertainty. Narrative plays a big role in Damn, but all the stories are interrupted. Habit dictates we treat Kendrick as the reliable narrator we want him to be—Damn’s slip and slide through otherwise voices (his cousin, his mom, Deuteronomy, Fox news, Rihanna, Kid Capri) and sporadic access to his own suggests we rethink that assumption. The song titles, uppercase and punctuated, tease a kind of closure that the songs themselves withhold. Even with chart favorites like “Humble” and “Loyalty” voices are layered (and competitive), diverse, and mediated.

To Pimp a Butterfly may be Kendrick’s unequivocal love letter to black folks stateside, but Damn best sounds the dizzying array of multi-level micro-adjustments that mar and animate black life, period. In a post-fact world of sorts, Kendrick enacts black life as the ultimate counterfactual, an irreconcilable knot of histories, doctrines, spirits, and sounds. “I can feel it, the scream the haunts our logic,” he grates on “Feel.” It’s a helluva heritage, but as Damn proves, these mixed grooves make music for the ages. —Lauren M. Jackson

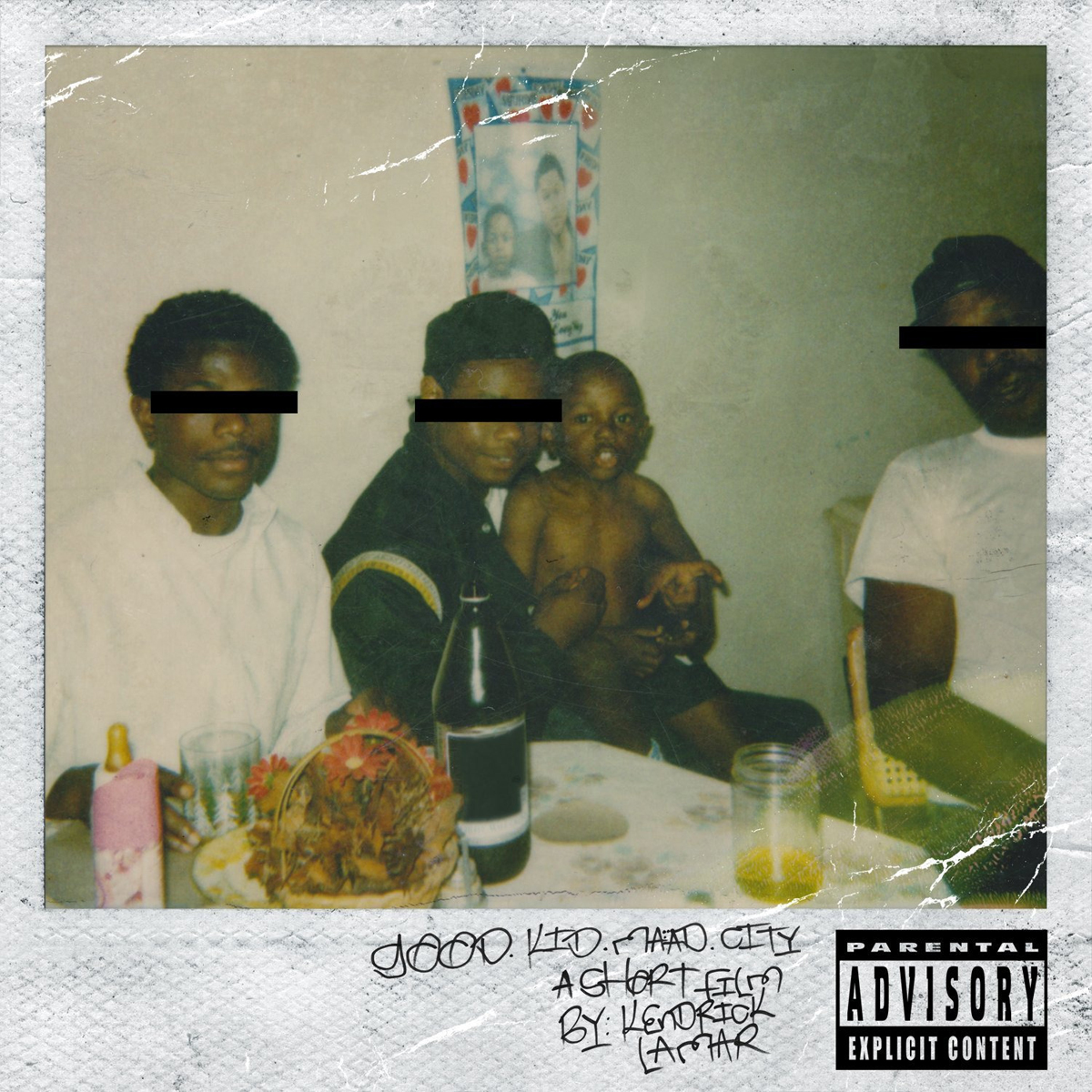

1. 'Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City' (2012)

Label: TDE, Aftermath, Interscope

Producers: Dawaun Parker, DJ Khalil, DJ Dahi, Hit-Boy, Jack Splash, Just Blaze, Like, Pharrell Williams, Rahki, Sounwave, Scoop DeVille, Skhye Hutch, T-Minus, Tabu, THC, Terrace Martin, Tha Bizness

Features: Jay Rock, Drake, MC Eiht, Anna Wise, Dr. Dre

On “The Art of Peer Pressure,” the fourth song from his masterpiece, Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City, Kendrick Lamar puts you beside him in the backseat of a white Toyota sedan, quarter-tank of gas, one pistol, some orange soda. It’s the sort of aimless driving you do when you’re 15: long, laconic loops through your own neighborhood, maybe crossing over into foreign territory to look for sex or trouble or cheaper tacos. And there’s something about the Jeezy line.

You must remember those afternoons. The handful of hours between school letting out and your parents getting home stretched and dilated into a sort of parallel existence—you were braver, wiser, more sure of yourself than you ever could be in real life. Everyone in the Toyota is ready to grab South Central Los Angeles by the throat and shake it until it’s dead; everyone in the Toyota is taking “Trap or Die” to heart.

Everyone, that is, except for Kendrick. “Bumping Jeezy first album, looking distracted.” The premise of Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City is that the outside world has the power to corrupt. That’s clear enough: the smog, the gangs, the fried food, the Riots. It all flows through adolescent Kendrick. Like so many American kids, his nerve endings are being sparked and pulled in too many directions to study Thug Motivation 101; he settles for it washing over him.

What makes Good Kid such a uniquely thorough reading of the human condition is that the good kid isn’t always good—or more specifically, isn’t good through and through. When his friends want to rob a house or stage a break-in at Kendrick’s job, or when a beautiful girl on Myspace lures him to unfriendly blocks, it unlocks something deep within Kendrick, something at odds with his better judgment. That’s why “Backseat Freestyle” is so important: that youthful bravado is sort of silly, but it’s also one of the basest feelings a teenager can have.

Good Kid spends a lot of time reconciling Kendrick’s better self with his gut-level desires: that’s what “Peer Pressure” is about, and it’s where the album ends up, with its third-act religious awakening. But at its best, the record gives itself fully to the dark side. “Money Trees” is about the literal and psychological preparation for a home invasion, from freestyling in the Toyota while he and his friends scope out a target to throwing gang signs during the getaway. Of course, that’s only the framework. Kendrick’s mind spirals beyond, to the memory of an uncle who, before he was murdered, predicted his nephew’s musical success. “That Louis Burger never be the same/A Louis belt will never ease that pain.”

Or take “M.A.A.D. City,” where he taunts you (“Fuck you shooting for if you ain’t walking up, you fucking punk?”) and lays out his moral code (“You killed my cousin back in ‘94, fuck your truce”). There’s the unabashed love from “Poetic Justice,” the windows-fogged lust of “Sherane,” the chest-out triumph of “Compton.” Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City might have been painted as a moral reckoning, but it’s really a detailed, even empathetic look at our most impulsive natures, because sometimes those are the selves we have to face. —Paul Thompson

SHARE THIS STORY