When Phil Knight calls, you pick up the phone. When a captain of industry has an idea but no executor, the first thing he needs is an audience. For Knight, who co-founded Nike in 1971 and turned it into the world’s most powerful sneaker brand in the ensuing decades, the idea was to find a way to get college-level athletes paid.

Radical changes to state law and NCAA rules that went into effect on July 1 meant that, for the first time ever, athletes at schools across the country would be allowed to profit off their name, image, and likeness without jeopardizing their playing careers. Knight, whose company helped establish the idea of a player’s image as currency through gargantuan deals with superstars like LeBron James and Michael Jordan, figured there was some way he could use the new rules to help student athletes at the University of Oregon, his beloved alma mater.

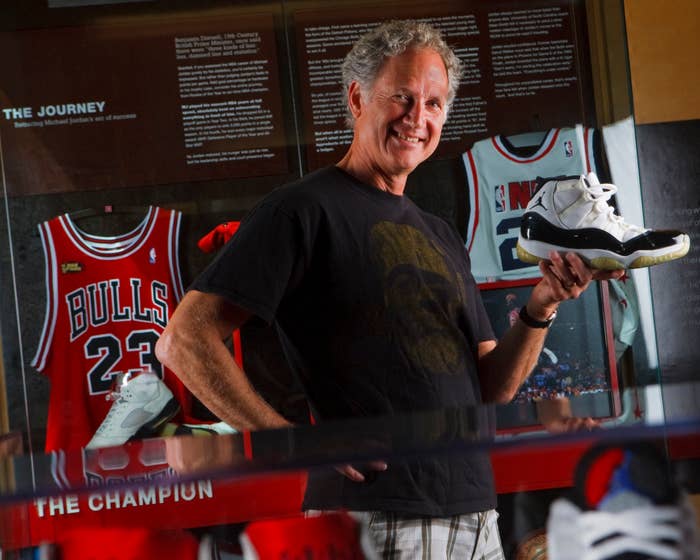

The audience on the other end of the phone was Tinker Hatfield. At 69, he is still Nike’s most celebrated designer and, beyond that, the most influential sneaker designer there is. He is responsible for a majority of the most important Air Jordan and Air Max shoes. His first name is among the most appropriate ever given to a human being. Hatfield is warm in conversation, a reservoir of the goodwill he’s accrued. Having worked at Nike since 1981, he is well acquainted with Knight’s challenges.

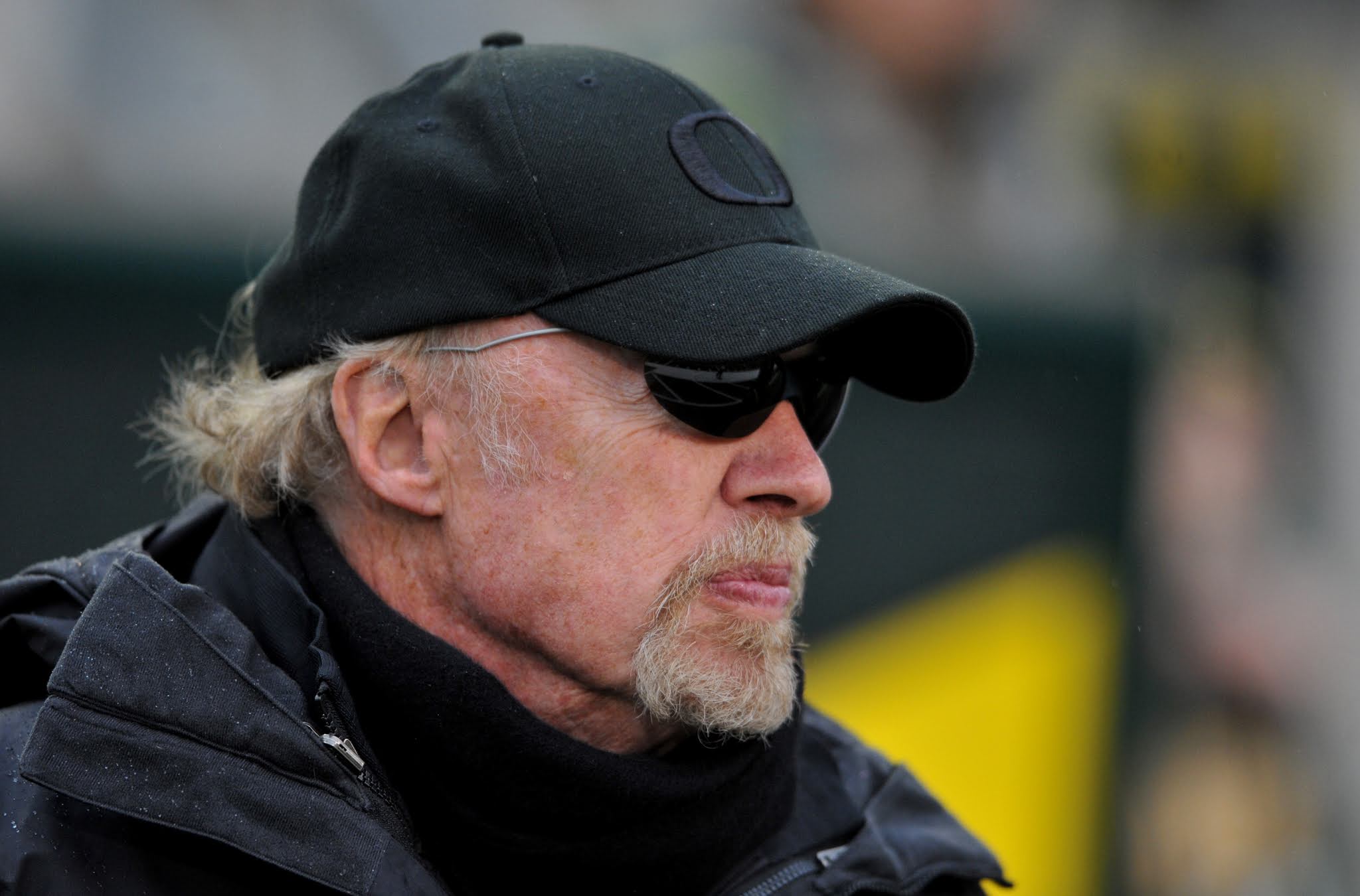

Both men were student athletes on the Oregon Ducks track team before transforming the sportswear industry. Hatfield was a school record-holding pole vaulter who competed at the 1976 Olympic Trials and Knight, at the end of the 1950s, a middle-distance runner under the mighty coach Bill Bowerman, with whom he co-founded Nike. They remain engaged fans and frequent attendees of Ducks sporting events. Knight, 83, is a wizened spectator on the sidelines, often hidden behind a black pair of wrap-around shades. Hatfield’s work permeates the athletic programs through sneaker designs, logos, and more.

Now, they’re testing new boundaries that question the fundamentals of traditional agreements between schools and the players who represent them.

“One of the big motivations here is to take advantage of the rule change,” Hatfield says, “and try and set some kind of example for how athletes can start to benefit more from all the work they put in and all the stress that they endure and the injury issues.”

At Knight’s prompting, Hatfield created a piece of art featuring star Ducks defensive end Kayvon Thibodeaux, and turned it into a non-fungible token, a digital art piece that Thibodeaux could sell. It shows him in three different poses, his name stretched big across the background and Hatfield’s signature scribbled into the corner. The Ducks player announced the NFT on July 6 and has listed it on marketplace Opensea, where editions are selling for 0.045 ETH (around $89.12) each.

Though Hatfield and Knight are inextricably linked with Nike, the collaboration between them and Thibodeaux on the NFT does not involve Nike in any way—the brand hasn’t offered a public stance on the NCAA rule changes.

For the sportswear execs, two men who have given considerable money and energy to the University of Oregon, it is a move toward creating a more reciprocal relationship for athletes who bring in money at top schools without reaping direct financial benefits. They are keen here to play just within the rules, even though neither made history by adhering closely to them. Knight is more cunning than his bored, set gaze suggests, and Hatfield can be brazen, operating with a level of independence afforded by his storied career.

Their work with Thibodeaux is a hopeful experiment, a suggestion that talent at universities like Oregon deserve more than room, board, and tuition.

“Everybody else is making—everybody else meaning the advertisers, the NCAA, the coaches—they’re all making millions and millions of dollars,” Hatfield says. “So Phil Knight has really been driving this particular project. And he called me up and said, ‘We’ve got to do something.’”

The NFT world is new territory for Hatfield, but that seems to be the kind of territory he is most comfortable in. If there is a new frontier he will be there, likely wearing a fedora. As a designer he’s turned the invisible physical by exposing the cushioning on the first Air Max model in 1987, turned the theatrical practical when he made Marty McFly’s self-lacing shoes a reality, and been involved in an incredible number of classic Nike shoes.

In this interview, he discusses his intentions with the Thibodeaux collaboration, his views on paying college athletes, the perks and pitfalls of exclusive footwear, the sneaker resell game, and more. It veers well beyond his day job as Nike’s vice president of design and special projects, Hatfield narrating through different scenes and subcultures. The conversation has been edited and condensed, its wider tangents trimmed to better tame the wandering portfolio of Tinker Hatfield.

The project was made possible by the changes that allow players to profit off names, image, and likeness. How important is that to you that they’re able to get paid?

I think it’s extremely important. Now, I was a full-ride athlete myself, in the 1970s, in track and field. And I remember, even though I was being taken care of within the rules of a full-ride scholarship. I mean, there was so much work involved.

Did you ever feel like you should’ve been compensated when you were at Oregon?

I never thought about it, to be honest, because I was just happy to be on the University of Oregon track team. If I hadn’t been injured my sophomore year, they were going to throw me out on the football field, too. But the reality was I just remember not having any money. I remember not being able to call up somebody and ask them out on a date because I couldn’t afford to take them anywhere. And here I was with a full-ride scholarship. I was signing autographs, well-known around campus, and yet I wasn’t definitely in the same situation as maybe other people. A lot of kids go have jobs during their schooling.

Did you have a job when you were there at the University of Oregon?

No, no. I think that’s cool because you actually can maybe accumulate some kind of way to pay for other things as you go through school. But my job was I barely could squeak by trying to be an architecture student. And then I got injured, and I was doing rehab. And of course there were the practices before and after and during, and the travel. There was quite a lot of time involved. So I felt like I had two jobs.

But the reality is, in today’s world, the players, and let’s just sort of look at football as an example. Maybe 20 or 30 years ago, there was probably less training, less film time, less practice time, less sort of, studying the opponent, less everything. So these players now, the number of hours they have to put in is probably double what it was.

It’s a lot closer to a professional level.

Yeah, it really is. And I’m close to the program, and, of course, I know people from other programs. And I see it firsthand. And I’m like, man, it’s incredible what these young people have to go through. It’s the same in basketball and other sports. And it’s the same for the women. I think Phil Knight, again, has accurately identified something legal that we can do to help people do better financially while they’re in school. And we also know that for every athlete, male or female, that makes it beyond college, and maybe makes some money that way, there are a thousand that don’t.

The sad part about the way the NCAA works, in my opinion, is that they don’t have a post-college safety net for athletes who probably didn’t have as much time to study and didn’t make pros. Or if they did make the pros and they were out maybe a year or two, they’re kind of just floating around trying to figure out what they’re supposed to do next. I think that’s something that we can help change. So that’s why we’re doing this.

How did you land on the NFT thing?

Well, Phil Knight called me, and he said, “What do you know about NFTs?” And I said, “Not much.”

Really? I would’ve thought that Phil Knight would be the guy who wasn’t necessarily aware of the NFT world.

He wasn’t that much. Evidently, someone had mentioned to him that in the world of art there were some people making really enormous amounts of money selling these non-fungible tokens. I didn’t even ask him how he knew about it. But he asked me what I knew, and I said, “Not much.” And he said, in his typical fashion, “Well, figure it out because I need you to do something with Kayvon Thibodeaux.” And he had identified Kayvon as a charismatic and, of course, very visible athlete. He’s somebody that we thought that we could work with. And it turned out to be the case. He’s fantastic. He was just at my house the other day.

A couple days ago, he came over, or drove up after the morning practice and film session. Drove up. And I had already had some of the images printed out. We signed a few together. I’m not quite sure what his plan is. But the reality is, I did the art. I didn’t even talk to him. He didn’t even know I was doing it. I did the art. And then somebody contacted him, and I think he was game to do this whole thing. All these years, I’ve been very careful not to contact athletes myself.

You’re not allowed to.

I’m not allowed to contact them. But if they call me or come over and say something to me, then I can engage in a conversation. But it has to be initiated by the athlete. So in this particular case, someone contacted him, and then he contacted me to find out more about what I had done.

And so then I sent him an image, and he liked it. I told him that we were already in the process of turning it into a non-fungible token. And I had to basically rely on a code-writing digital expert here that I know. He helped set up my account. And then you have to go through several steps. And then you have to mint the image. And then the idea was to then sell it. I sold it to Kayvon because I couldn’t gift it to him. So even though the rules have changed, there’s still something…

You still can’t give something to someone.

I can’t gift him anything. But the way it works through this cryptocurrency process is that we entered into an agreement. And he also had to enter into an agreement with the University of Oregon. And both entities, me as the artist, and the University of Oregon, because their logo is in this art, we took the minimum amount of the potential proceeds. So my take on it would be 12.5 percent. And the University of Oregon, at first, was going to do the same. But then they were able to do a special sort of one-time exclusion and got their take down to 10 percent.

But the reality is that Kayvon, when it’s all said and done, he owns this file. And let’s just say he makes $100,000. He gets to keep roughly 78 percent of that. That’s the hope, is that it goes into a level that’s actually meaningful.

Tinker, how much influence do you think Nike can have in these conversations about athletes being compensated at a college level?

I did this just with Phil. Nike didn’t even know about it. And there was a reason why that was the case. Nike has not really portrayed a position. And I think they’re working on it right now. So we’re careful, I’m careful anyway, to distance ourselves from Nike.

And even though some of the media mentions Nike, Nike has really no involvement right now. And it’s partly because Nike has to craft some kind of position on the whole thing. So I think this thing happened pretty fast. And the rule change occurred, I think, on July 1. And I believe Nike’s, again, trying to weigh the pros and cons of making a statement. So, what do you say?

We have so many—we meaning Nike—has these relationships with the NCAA and the actual universities. And they may or may not be very keen on all of this. But I want to be really crystal clear that this is Phil Knight and myself as individuals trying to help college athletes.

Do you think there’s a future in which sneaker brands could give endorsement deals to college players? Is that something we might see in 10 years or less?

That’s a great question. I thought about that but maybe for a minute. But it seems to me, to take out some of the ambiguity of the whole thing, that it would be fantastic if there was a policy that would allow company endorsements for the athletes. I think that would be an interesting solution. Now, I don’t understand the legal issues, and of course the complexities of working with state and private institutions, and then of course those folks back in Indianapolis. But the reality is, it seems to me like there might be.

Well, I’ll just say this. Phil Knight, he’s a provocateur. He provokes change. He’s an innovator. He’s not a designer, but he’s an innovative thinker. And I think that sometimes he gets a little bit frustrated with, I believe, institutions that don’t think a little bit more outside the box. So I think this is maybe his way of poking the ant hill a little bit, and then maybe there will be a bigger and better solution. I don’t want to speak for him, but that’s just an impression that I have

I think one of the ways that college players have been quietly getting paid before all these changes is by selling exclusive sneakers they’ll get from a big school like Oregon. Do you think athletes should be allowed to profit off that, or is that something separate to you?

Well, the way it works at Oregon anyway, I cannot speak for any other school because I do these limited edition designs, Jordans in particular, for men’s football and women and men’s track and men and women’s basketball. So those particular sports, I do these limited edition sneakers. And Nike pays for some of it. I pay for some of it. It’s kind of a little bit loosey goosey about who’s covering that cost.

Wait, Tinker, you pay for those sneakers out of your pocket?

I do. Well, some of them. I mean, a certain amount, yes. I want to, personally, just contribute. And what it does is it shows a commitment on my part to do something good for the athletes.

But to read the rules for the whole sneaker thing is that they get to wear them, and they don’t get to keep them until they are finished with their eligibility. So they wear them, and they check them back in to the equipment organization. So the equipment managers receive them back. They’re all numbered. They have this elaborate sort of system of locks where they keep each athletes’ shoes in there.

And then depending on whatever the team or the athlete’s doing, they check them out. And then they get to wear them, and then they bring them back. Then once they are finished with their eligibility, then they get to keep them. And you’re right. A lot of those athletes sell them to sneaker collectors. I’m going to just throw a number out. There’s probably no more than about 300 pairs that might go to, say, the men’s football program, and maybe a couple hundred to some of the other programs. Just fewer people. But we hold some back, by the way, for all the influencers and rappers and movie stars and whatever and pro athletes who call. As soon as one drops.

Do they call you directly?

Oh, yeah. I’ll be talking to somebody, and I won’t mention any names, but I’ll just tell you a story. I’ll get a call from somebody famous, and I know they played at Texas or something. And I’m like, “So you want a University of Oregon limited edition Jordan?”

Like, are you an Oregon fan now?

And I said, “But you went to Texas. How could you do that?” And they’re like, “Oh, no, no, no. This is not about that. This is about like these are, like, so cool.” [Laughs.] And so I’m like giving them a hard time. But then we definitely try to cover those people as best we can, because it definitely is, I guess you’d say, an interesting storyline. But it’s also the publicity ratchets up depending on who wears them.

But for people who end up selling them, does that offend you on a personal level, or do you feel like that’s still OK in this whole idea of athletes being able to profit in some way?

No. I think it’s fine. Although sometimes I wonder if they’re not maybe short-sighted. Because if they held onto them, they not only maybe might appreciate them and keep them, or if they held onto them, they would actually appreciate in value. But they tend to not be very sophisticated so they just sell them to a collector. And there are all these people that track all this stuff and are calling them and whatever. And I think they undersell. The collectors know a whole lot more about it than the athletes.

But I will tell you a quick story. Several years ago, we were doing shoes for the football team. And then basketball season was coming around, and we did some shoes for the basketball team. And again, we’re talking about just a very limited number of shoes. And then I’m like, there’s the Pit Crew at Oregon.

I was on campus when the Pit Crew Jordan 3s first came out. That was a big moment for me personally. I remember later on, when the football players got the white pair, and there was a guy who lived in the apartment below me, and I saw he had them. Like, oh my God.

Sometimes I still am amazed at how valuable people think these things are. So I was in contact with the president of the Pit Crew, and I said, “Look, I have done up a Pit Crew version of these shoes,” and he about fell. I could tell on the phone he about fell out of his chair. And I said, “But here’s the deal,” I said, “I want to encourage the Pit Crew to go to more than just men’s basketball games. So here’s how I want to do it. I want to send you 80 pairs, and you hand them out—being the president—you hand them out to the people who have gone to more than just men’s basketball.”

In other words, kind of, he developed a point system. And the point system got you on the list to get a pair of Pit Crew Oregons. And by the way, those are some of the most sought-after because there weren’t as many.

Anyway, I sent the 80 pairs down. We sent them down, and they got handed out. And the idea was that when other people kind of got with the program and started going to support, say, women’s volleyball or whatever, then we’d send more. Because I had about, I’m going to say, about 280 pairs, I think.

And I thought, well, the Pit Crew basically won these or earned them by going and supporting not just men’s basketball but other sports, that they’d hold them in high regard and be very cool on campus if they wore them. Well, the very first weekend, six of those pairs went onto the secondary market. So I called up the president. I don’t really follow this stuff, but I had people tell me, and so we looked it up. And sure enough, six out of the 80 pairs.

And I immediately called up the president, and I said, “I am hereby suspending this entire program.” And he was bummed. And I kept the other roughly 200 and, say, 20 pairs. So there were only 80 that actually went to the Pit Crew. But I said I considered it a failed experiment. Because they’re not playing sports, so they could sell them immediately, and some did. And they were going for a couple grand or whatever. But then they quickly escalated to like six or seven grand after the collectors got them.

So I just stopped. I said, “Look, I can’t do it.” I am not a cash machine. I’m not an ATM for the Pit Crew. I’m just not going to do it that way. As much as I really appreciate the fact that they’re supporting the basketball team, I just told him, I can’t do it.

So then what we started doing with the rest of the Pit Crew shoes was we started giving them out to other people. By the way, again, the influencers and rappers and pro players, and also certain people that are known sneaker collectors that we’re friends with, we just started judiciously sending them out. So they were leaked out or they were sent out in a very measured and slow fashion. And actually, I still have some. So those became very, very popular because of that extra level of exclusivity. So those six people who sold those sneakers blew it for the rest of the Pit Crew, in my opinion. And I think that the president felt a little bummed, obviously, about the whole thing. Because he probably should have encouraged them not to do that. But I don’t know.

It’s kind of something you expect at this point, where we’ve gotten to a place where any pair of remotely desirable sneakers is going to be resold. How do you feel about how big the whole sneaker resale market is at this point?

I think it’s OK. Definitely it’s a bittersweet thing where you know that some people just love them, and they want to get them, and they search for them, and you find a guy like PJ Tucker, who plays for Milwaukee now. He was wearing a pair of shoes that was for another player. He just loves sneakers. He would never sell. You know what I mean? He’s got a huge collection. And I think that’s really fun. And if he did sell them, it was kind of like, “Well, I’m trying to get this one versus that one.” And there are all kinds of rock stars and rappers, like I said, and people. And sometimes they trade.

I just think it’s kind of fun overall. But I also realize that there are some more business-minded people that have figured out how to make hundreds of thousands of dollars over the course of a year or so by using bots and getting exclusive sneakers before anybody else. And then, of course, it’s a business transaction. So that part maybe doesn’t thrill me as much at all. But I think that was probably predictable. Right?

Yeah, like did we go too far? Did we do too much to make these things so desirable?

Maybe so. I don’t know. I mean, a lot of people used to… well, not a lot. But I would get inquiries from people who would blame me for violence around sneakers. Like a kid gets their sneakers stolen, or gets beaten up, and maybe in some cases even severely injured. And they were trying to blame me or blame Nike for this phenomena. And my answer to the reporters that I did speak to about that was we’re just trying to do a great job with the design work, and we’re trying to create great performing shoes and also objects of desire. I think it’s more of a societal issue that people would commit violence to obtain something materialistic like that. So I tried to sort of move the conversation toward just lack of morals or just people with lack of opportunity, and this is one way they could get something valuable was to just beat somebody up and take their sneakers. So I mean, I just couldn’t figure out any other way to describe my position. We’re just trying to do great stuff. And we have no control once those sneakers go out.

Do you pay attention to the frustrations people have with it, like people getting frustrated over the Nike SNKRS app?

It’s a funny thing, I kind of keep my head down. And I’m working on stuff all the time, inside and outside of Nike. So I don’t really pay attention or understand the Nike app and sort of Nike’s desire to get people to join in and then get access. I don’t necessarily have an opinion about it because I try not to be, I guess you could say, distracted by that kind of thing.

But having said that, I don’t know if in the long term it’s going to be a good thing or not. I mean, I think, of course, time will tell. I don’t know numbers. I pretty much try to protect myself from knowing too much, because then, say, in an interview like this, I might say something that’s inaccurate or maybe not in keeping with corporate policy. So it’s best if I don’t even know half the time.

I just think it’s related to the NFT project you’re doing, in a way, in terms of the whole ecosystem of sports and sportswear being so digital. Do you see more NFT things happening at Nike in the future?

Yes. Again, I’m not going to speak for Nike, but I’ve already done two or three more art pieces for other players. They don’t know about it. We’ve actually created the NFT for them. But we’re sort of reluctant to start spitting them out too fast and too furious. But we want to learn from the Kayvon project before we get too much more aggressive about this whole thing. The plan, I think Phil and myself, I think we think that we can probably continue to do it. But I think it’s a sort of wait and see attitude a little bit until we try it again.

So we’ve been talking to Kayvon about the process of how he should handle this image, this file, the NFT, how he should handle it himself. He owns it, so it’s his property. And he can sell that entity or that, well, in this case, the artwork any way he wants. He can sell copies over and over and over again to literally hundreds of people who might want to have one of those posters. Or maybe he’ll find somebody that wants to own the file themselves and will pay a large amount of money. That remains to be seen.

I’m, again, trying not to be too intrusive. I mean, I’ve been talking to Phil, but I’m trying not to influence the athlete much, because he owns it. It’s his personal decision. And I think he’s probably talking to all kinds of people about how he should do it. He’s just such a big and powerful guy, but he’s also sharp as a tack, and he is putting a lot of thought into this. And he’s also willing, which that’s part of I think why Phil chose him is that I think Phil knew him enough to know that this guy could probably handle it and not let it mess with his mind. He’s very solid. Very solid young man.

Yeah, so NFTs, there might be some people that could get fully engrossed in this thing and spend all their waking hours trying to figure out what to do with it. But I think Kayvon’s way more sophisticated.

So you’re in the NFT game. You had that Michelob collaboration before that. Can you talk about any other non-Nike projects you’ve been working on?

Yeah. If you go on Zero Motorcycles’ website, the electric motorcycle company out of Santa Cruz, I collaborated [with them]. Zero Motorcycles is like the most successful of all the electric motorcycle companies. And they’ve been at it for maybe 10 or 12 years, and they’ve been doing quite well. They finally came out with this really monster super bike version of an electric, and I have one.

But anyway, I got contacted through a company here in Portland called Kamp Grizzly and an individual Peter Jasienski. He’s a friend of mine. He contacted me and said, “Look, Zero would like for you to collaborate with a guy named Thor Drake, who owns See See Motor Coffee Shop here in Portland. He’s a well-known motorcycle modifier and he races. He’s a good businessman. He’s got this real cool brand called See See.”

Anyway, we met. And then I did a bunch of drawings of what I thought how we could take this super bike that they had, which kind of looks like maybe like a real high-end Italian motorcycle, like something real snazzy. They wanted us to sort of modify it and make it into a show bike that was just super unique. And so we basically kind of steampunked it. He basically tore the whole bike apart, and based off my drawings and his own creativity, Zero now has this show bike that they’re about ready to start promoting around as kind of a brand image thing. So there’s a little bit of a kind of Portland hipster punk, like people with tattoos. It’s like a little bit of Portlandia somehow made it on this motorcycle. So I’m pretty proud of that.

Are you saying you’re a Portland hipster, Tinker?

I’m not. I’m not. Some people might think that, but I’m definitely too old, and live in a different circle of friends. However, I’m a good observer. So I thought, well, why not tap into that vibe, if you will. So I did. So the seat and part of the motorcycle looks like tattoo art like you’d see here in Portland. And Thor redid the tank, which is really basically a storage compartment. Because this is an electric bike, it doesn’t really have a gas tank. But it looks like it has one. And he redid that in polished aluminum with rivets like an Airstream trailer. And we sent out the wheels to get painted in a wacky color.

The taillight, I sketched this up after looking at an electrical transition lining. Anyway, there’s kind of a storyline around trying to think about electricity, Portland, and the fact that Santa Cruz is kind of cool and hipster-y as well, if you think about it. And I think it’s something they were really happy with. I think they’ve actually started promoting this bike as like an art piece that helps with their branding. So it’ll go to shows and get photographed. I think it’s already started. They call it a collaboration between Zero, Thor Drake, and Tinker Hatfield.

Any chance we can get an HTM reunion, get the band back together?

You know, I was just thinking about that. I went to a concert last night, first concert I’ve been to in a while. And I was wearing a pair of HTMs.

What was the concert?

Liv Warfield. She sent a tape in to Prince, and ended up becoming a backup singer for Prince’s all-girl backup band called 3rdeyegirl.

But anyway, so I went to that concert last night, and I ran into a bunch of musicians that were there that I know. And they all said, “Oh, I can’t believe you’re wearing those HTMs out here in this dirty, gravely parking lot.” Blah, blah, blah.

Which HTM sneaker was it?

It’s the one, it’s when Flyknit first became a technology for us.

HTM Lunar Trainer maybe.

We did this wacky version. And by the way, Nike wasn’t digging Flyknit, at first. So that’s where HTM comes in kind of handy. We were able to basically introduce Flyknit to the world through HTM, because nobody else gets to make that decision but Mark and I and Hiroshi. So it’s called LunarEpic. It was a running shoe, but it’s really got this sort of extra tall collar on it.

Anyway, it’s an HTM project. And a bunch of people recognized it, and they’re just like, “I can’t believe you’re wearing that out here and getting those things dirty.” And I said, “Oh, you know, I’ll probably get another pair somewhere.” Anyway, so that was fun. It was really a great experience last night, because none of us probably had seen very much live music until just now.

So this woman, young lady, wasn’t even a real performer. But she somehow got connected with Prince. And he was so impressed that he heard her and she became a regular in his band. And I remember, we had Prince play for a Michael Jordan party at the last time the NBA All-Star game was in New York, a few years back.

Did they play basketball together? Because I know Prince played basketball.

[Laughs.] I don’t know. That’s a good question.

She’s become this incredibly powerful performer. And she spent some time here in Portland on the track team before she decided to become a singer, or became a singer. And she’s killer good.

So she killed it. She was a track athlete. She’s from, I don’t know, back east. But she came out to Portland State to be a pentathlete. And then I think she got married or had a baby here. And she started singing in a band with local musicians. And they said she was so nervous she wouldn’t even face the audience at first.

Anyway, somehow Prince saw a recording of her doing something and was smitten, and hired her. And now, of course, she has a few years under her belt, and she’s killing it. It was funk. It was a little bit of Prince-like music, but it was more funk and soul and blues. And she hired almost all of her—just for that performance—almost all of her old bandmates that were here, to perform with her. And it was just unbelievable. And I actually know almost all of those people, just because of the music scene.

I gotta go back. Is Michael Jordan a Prince fan then? Because I feel like you would’ve designed a purple pair of Jordans for him at some point.

[Laughs.] Well, yes, he is a Prince fan. And I’m sure he still is even though, of course, Prince is gone. But the story about Prince showing up and performing, he brought his whole band, 3rdeyegirl. As I understand it, he didn’t really want to do the gig because he had to bring everybody from Minneapolis or whatever. The last second, he finally agreed to do it.

His set, this big huge party, started at 1 in the morning. I got advance notice. It was in this big building where there were different things going on in different parts of the building, different floors. Like Ariana Grande was doing something somewhere. And there were all kinds of celebrities all over the place. But I got a tip that Prince was going to play. And then we found out what part of the building he is. And we’re talking about maybe 200 people. He’s playing to 200 people, which would be intimate for him.

So I was standing right underneath his microphone. Three-foot high stage, his microphone, and I’m looking right up at him. It was incredible. But Michael was, like, two people behind me, and he was grooving. He was having a good time. So yeah, he’s a Prince fan, for sure.

Did you give Prince a pair of sneakers?

I didn’t. But we have an entertainment marketing guy named Reggie Saunders. Maybe you know him.

A legend. Reggie is a legend. I’ve never met him personally, but his name is paraded around so much.

Oh, he knows everybody, and he takes care of everybody. So Reggie has sent a lot of stuff to Prince. And Reggie was the one who actually kept kind of working the beat to get Prince to show up, so he deserves a lot of credit for that. And it was a marvelous performance. And I think Prince passed away just two or three months after that. That’s my recollection, it could be off by a month or two.

So Michael was, I’d say, it’s safe to say he’s a pretty big Prince fan. And his wife Yvette was definitely a Prince fan. They were just boogying behind me. And I’m standing next to Queen Latifah. On the other side of me is Chris Rock. The scene was just ridiculous.

I want to take it back to Oregon real quick, because we actually ran a story about Oregon Air Jordans and things like that, and one of our writers had talked to Dennis Dixon about his experiences with those shoes. And he mentioned that there was some moment where Michael Jordan had some criticism around the Jumpduck logo that turned the Jumpman logo into a duck.

Oh, yeah. He did not like it at all. He said, “Don’t mess with my logo.”

So Michael Jordan’s a Prince fan but not an Oregon Ducks fan.

[Laughs.] I would say that he is definitely a North Carolina fan, and I’m not so sure he’s a Duck fan. Let’s put it that way. He really objected. I did it without asking him. I turned the Oregon Duck into the Jumpman. And you probably saw it on the back of one of those limited edition shoes. And he called me up and gave me hell for it, so I agreed not to do it again.

But I’m one of those people that just goes ahead and does whatever I want and asks for forgiveness after the fact because I don’t like being told no. You know what I mean? So I don’t mind being scolded for having done something, but I don’t like to be told no. So I tend to operate that way anyhow.