Terrence muthafuckin’ Howard.

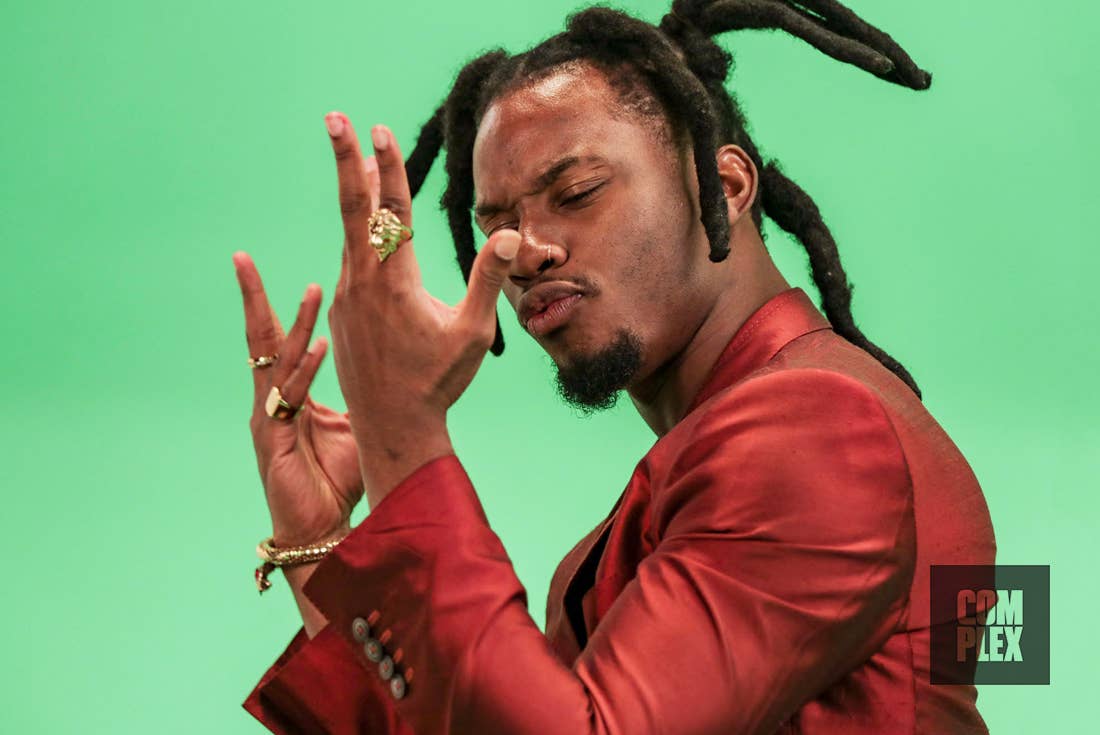

It’s 8:30 a.m. on a Friday in mid-November and I’m on my way to join Denzel Curry at a video shoot for his next single, “Black Balloons,” featuring Twelve’Len and GoldLink. I hurry to board the Mercedes-Benz Sprinter van Curry and his team occupy, eager to talk to him about the evolution of his career, but all he wants to talk about is Terrence Howard.

“I’m Terrence muthafuckin’ Howard—don’t you see my movies?” he asks half-jokingly as I get settled in the van. We’re on our way to Newburgh, about two hours north of New York City, for the shoot, and we have to kill time while waiting for GoldLink to come downstairs from his hotel room.

Curry takes the opportunity to break down scenes in which Terrence Howard has shed tears as an actor. And let me tell you—there are a lot.

“I cry in every single one,” Curry says, still pretending to be Howard. “Shit, The Best Man, I cried because I was about to get beat up by Morris Chestnut. Shit, Best Man 2, I cried because his wife died. Shit, Big Momma’s House, I cried when I got kicked out a window. Shit, Four Brothers, I cried when I got shot by my partner. Shit, Idlewild, I cried when I was being bullied by Faizon Love. Hustle & Flow, those were real-nigga tears. The church scene, and then, ‘I’m tryna squeeze a dollar out of a dime—and I ain’t got a cent, mayne!’ I was ’bout to cry. All my movies, I cry in. Shit, I cried in Iron Man when I found Tony Stark in the desert ’bout to die.”

Curry admits that he might be more sensitive than the characters Howard usually plays. “I’mma tell you, my daddy was the one who pointed that shit out,” he says. “He was like, ‘You cry too much. You cry more than Terrence Howard in the movies.’ I was like... ‘Terrence muthafuckin’ Howard.’”

Curry, 23, has been visible online since at least 2013, when he dropped his debut project, Nostalgic 64, and I can’t say I remember ever seeing him cry. Instead, I’ve seen the opposite: rage, aggression, and chaotic energy—all of which have become important elements of Curry’s music.

For years, he’s been perfecting his messaging and delivery, and he connected on a mass scale this year with “Clout Cobain,” the standout track from his latest album, TA1300, released in July. The song’s video (which currently has almost 45 million views) brilliantly features a circus of drugged-up, face-tatted clout chasers who laugh when Curry’s clown-like character performs the latest dance crazes and hops on a faux Instagram Live toting a gun. Later, when Clown-zel commits suicide, they don’t miss a beat and keep the party going.

It’s pointed commentary on the new wave of “SoundCloud rappers” who will do just about anything for a dollar and a chain. But well before the present scene popped off, Miami rapper and producer SpaceGhostPurrp helped pave the way for independent, underground MCs and producers to succeed, pre-SoundCloud. He heavily influenced his home state of Florida almost single-handedly with his Raider Klan crew, which Curry went out of his way to join early in his career. “My main thing was, I was like, ‘Bro, I ain’t gonna let you down,’” he says, harking back to when Purrp made Curry’s Raider Klan membership official.

Curry counts himself as a SoundCloud rap pioneer, but the sub-genre has slowly folded in on itself, overcome by a gaggle of aspiring rap stars who fall into the exact category Curry is critiquing in “Clout Cobain.”

“I see a lot of people do some dumbass sh*t for clout—the stupidest sh*t for clout.”

In a nutshell, the video for “Black Balloons” is a prequel to “Clout Cobain.” It shows how Curry’s character transitions from an average rapper to the tortured clown who eventually ends his own life. The song itself is about elevating beyond the bullshit and letting go of a painful past. Curry’s vocals tend to skew toward the gravelly, so hearing Twelve’Len and GoldLink’s gauzy voices alongside him creates an aural counterbalance of shadows and radiance, a key theme of TA13OO, which was presented in three acts: Light, Gray, and Dark.

As we wait for GoldLink, Curry keeps the van entertained by pulling up a clip of an iconic scene from Sugar Hill, the 1994 Wesley Snipes film about a family torn apart by drugs. Then, within the span of a few minutes, he brings up Betty White (“How is Betty White still alive? What does she do? She a witch or something”), Napoleon Dynamite and Hot Rod (two of his favorite movies), and Jimmy Neutron and The Fairly OddParents (two of his favorite cartoons). The pop culture references are endless.

I’m joined in the Sprinter by Curry’s label rep, Chissy; his longtime manager, Mark Maturah; Twelve’Len; a very quiet driver who Twelve’Len elects to sit next to so he can sleep, away from the conversation about Terrence Howard; and 23-year-old painter and model Mónica Hernández, whose curly hair I find myself talking to Curry through as she sits beside him. “He randomly DM’d me,” she explains of their initial connection. “I went to his show, and we’ve just been hanging out since. We hang out whenever he’s around.”

After waiting for nearly an hour, it becomes clear that GoldLink isn’t coming downstairs. “And niggas were looking at me like I’m always late,” Curry says to his manager. “Mark, you gotta face facts, bruh. Every time something go down, you always looking at me like I’m gonna drop the ball. We left early.” He adds, “I didn’t drop the ball. Mark, you gotta understand, I don’t drop the ball all the time.”

Recalling a situation at a recent Miami Heat game, during which Maturah cautioned Curry not to curse in front of a crowd of families with kids, Curry imitates Maturah’s warning: “He’s like, ‘I know you—you curse a lot, Denzel. So I don’t need you to start cursing now.’”

“That’s not how I said it,” Maturah responds, measured and patient. “Everything I say, you take it and amplify.”

It’s an offhand response, but it perfectly represents the role Curry has grown into since Nostalgic 64. With the release of every album and EP that followed it, Curry has become more efficient at projecting the concerns of the world. He amplifies.

But the concern on this day is, he has a damn video to shoot. We leave after deciding that GoldLink will get his own Uber to the production studio in Newburgh, and the chatter stops completely for the duration of the two-hour journey. As everyone closes their eyes to nap, I listen through Curry’s discography in preparation for our sit-down interview, which is set to take place when we arrive at the shoot. As always, I get stuck on the Outkast-inspired Planet Shrooms half of his 2015 double EP32 Zel / Planet Shrooms—my favorite project of that year, without question.

“I’m just saying real sh*t. I’m not tryna save no one.”

When we finally arrive at the set, at Umbra of Newburgh Sound Stages, we’re given the grand tour, and Curry is whisked away to begin hair and makeup. Waiting for the shoot to get underway, I sit at a table in the kitchen area with Hernández, the model and painter. There, she tells me she was born and raised in the Dominican Republic before moving to the Bronx at age 6. I ask for her Instagram, where I find her work: six-foot-tall paintings of nude women, entangled together, two in one frame, or alone, or in the act of receiving head.

Her work has been seen and shared enough that Cultured Mag has identified her as one of 30 artists under 35 to watch in 2019. For kicks, I ask her to guess how old I am; she says I have “one of those faces” and could be 20 or 26, so she splits the difference at 23. When I reveal my big age of 29, she’s genuinely shocked. (Note: I have a baby face, ya dig?) I tell her her own fast-approaching maturity is right around the corner, to which she gives a quick but well-thought-out answer: “I’m not opposed to getting older—I just want to make sure certain things are in order first.”

At this exact moment, Curry moseys over to us and begins his second job as a standup comedian.

“White man get money—stay rich, kids get rich,” he begins. “Black man get money—it’s the countdown till, ‘When is this brother gonna go broke?’ I’m not going broke. But you know what they say: White man die, leave a will. Brother die, leave a bill.”

Those of us within earshot start cracking up, because his delivery, almost like a dramatized public service announcement, is fucking hilarious. But beneath the surface, it’s Curry presenting the shitty facts of life as pure comedy. In the next breath, he jokes about an extra looking like Samuel L. Jackson. “I’m tired of these muthafuckin’… You know that movie Die Hard?” He trails off, distracted.

At any given moment, Curry’s mind seems to vacillate between “How do I entertain?” and “How do I maintain?” His balancing act has proven successful thus far. His latest effort, TA1300, is both sobering and hype AF, a combination that made it one of the best projects of the year.

Curry’s exterior screams wild child, but he carries a thoughtful balance in everything he says, as both a person and a lyricist. He went “straight edge” (drug- and alcohol-free) in 2017, but his peers, especially those in the SoundCloud rap generation, did not. This very real juxtaposition eventually led to the concept of the “Clout Cobain” video.

In that video, Curry is calling other rappers out on their bullshit while commenting on the people who encourage their absurd behavior. When we speak on set, he elaborates on what inspired those visuals. “I see a lot of people do some dumbass shit for clout—the stupidest shit for clout,” he says. “I see it every day. I see it on social media the most. That’s where I really see it. All you gotta do is go on your Explore page, and you’ll see the stupidest shit. Everybody do some stupid-ass, coon-ass shit and it gets a million likes—maybe because people wanna see people do stupid shit. Because if you say some real shit, nobody wanna hear the truth. People wanna escape the truth sometimes.”

Curry couldn’t be more right. The truth is: We’re living in a fucked-up country that’s considered one of the best, and safest, on this planet. And yet, every day, black people are being stopped in the store, stopped on the street, kicked out of classes, kicked out of pools, considered threats at the age of 9 and younger, and outright murdered because of sick, ingrained, and dangerous stereotyping. That reason alone is why my stomach falls through the floor during two separate moments on the video shoot.

On set, Curry’s character is being enticed by a pasty white label executive who, at one point, tries to convince him to snort a comically large pile of cocaine. The prop on set is a heap of powdered sugar. Curry jokes, “What if I just snorted all of this?” One of the set leads, a young white woman, immediately responds, “Oh, no, you wouldn’t wanna do that. It’s just sugar.”

At this point, everyone working with Curry should know he’s straight edge. But even if you don’t, doing a bit of homework and, I don’t know, maybe taking four minutes to watch the “Clout Cobain” video would have been helpful? In response to the woman’s “advice,” Curry says, “Yeah… I know it’s sugar,” and reiterates his sobriety by saying, “This is how you know I don’t do drugs!” The simple fact that a member of his (albeit rented) video crew doesn’t respect him enough as an artist to even be aware of the theme of both videos—the toxicity of celebrity—speaks volumes.

“I wanna win Grammys off my album.”

Shortly after this happens, there’s a scene in which a $100 bill is needed. This time, a white man on the video crew speaks up, asking if anyone has one. He looks directly at Curry’s manager, Maturah, who’s dark-skinned with locs, and says, “You have one, right?” Maturah doesn’t, but an older white woman does. She retrieves it and they move on, but Maturah asks, “You saw that, right?” When I check in with Maturah after the shoot, he tells me neither he nor Curry were offended. “It was all a joke,” he texts. He and Curry have been navigating the industry for the better part of a decade now, so they’ve likely had worse experiences, but it says a lot that they’re willing to look past prejudices for the sake of maintaining good vibes and sticking to a schedule.

While the extras on set are mostly people of color, the video crew itself is largely white. In both of these situations, the crew members revealed their cultural blind spots. To hop up on my soapbox real quick: This is why diversity is important both behind the scenes and in front of the camera. It’s bound to hurt not only the morale of the artist, but also the quality of the project when the team pulling the strings doesn’t have any idea what the artist is about. Period.

Luckily for all of us, Curry thrives on the uncomfortable. He lives to make people sit in discomfort with him and help them work through it instead of dodging it. On set, he keeps the humor on 10, even during microaggressive moments like the aforementioned. During the several hours I watch him work, he grabs the extras and crew members and gives them shoutouts while also roasting them, going out of his way to maintain positive energy and make his collaborators laugh. To keep it a buck, part of a rapper’s job is to keep his or her listeners distracted as the world burns around us. Many of them, like Curry, grew up in less-than-ideal situations, and they’re committed to creating their way out of poverty, death, and destruction. Curry is incredibly aware of the inequalities that have shaped this country and his city of Carol City/Miami—which in turn shaped him.

“There are a lot of beautiful women everywhere, and there’s a lot of money, you feel me?” he explains. “[Money] that’s not in my pocket from my own city. It creates a thing where people gotta do fraud, scams, juugin’, home invasions, all that type of stuff. Because they wanna live this fast life and get it in quick, conning the next man to get something. That’s what it is in my city. And I’m not saying my city is all the way fucked up, because it’s beautiful at the same time.”

Curry breaks down South Florida’s demographics further, ripping off the Band-Aid to show how people who are living alongside each other don’t always mesh well. “Pretty much everyone is from the islands, or everybody is from the South, and it’s all blended together, which creates a crazy-ass melting pot and a lot of tension,” he says. “So that’s why we rap the way we rap, because the energy around us is so raw.”

In 2017, Florida was unstoppable when it came to hip-hop. The most dominant young rappers who sprung up that year were from the state, particularly South Florida. The late XXXTentacion led the pack, followed by Lil Pump, Ski Mask the Slump God, Smokepurpp, and a slew of others.

“I could listen to Lil Pump’s tape and it’s just full of bangers and shit,” Curry says when I ask for his thoughts on the new wave of Florida rappers. “When I listen to Ski Mask’s tape, it’s full of flows—like, ill-ass flows. When I listen to X, it’s, like, versatility. They all have their own niche. Not everybody’s gonna rap the same way. I don’t rap like them niggas. We all sound different as fuck, but we all come from the same place.”

Most of the rappers in this new wave followed the path of SpaceGhostPurrp’s Raider Klan. After being initiated, Curry claimed his set proudly on his 2013 breakout hit, “Threatz,” featuring Robb Bank$ and Yung Simmie. From there, Denzel and Purrp dove into musical experimentation alongside other Klan members and associates like Metro Zu; they worked together publicly, their collaboration yielding tracks like the Purrp-produced “Live This Shit.” But in 2013, the same year he joined, Curry announced he had left the Raider Klan of his own will. In early 2016, his private beef with Purrp went public, the two attacking one another for various reasons, and the feud spilled onto diss tracks. Later that year they squashed their issues, and now they’re back to bigging each other up on Twitter, with Curry regularly giving Purrp credit for birthing the sound and aesthetic that led to the 2017 Florida rap explosion.

When I ask Curry what it’s like to see his new peers blow up overnight, he’s quick to compliment them. “I’m glad to see people recognizing other talent that was brought in—especially if I brought them in,” he says. “It’s a good thing. It’s either I brought them in, Ronny [J] brought them in, or somebody from Klan or ASAP [Mob] ushered this new generation in.”

Curry is already a rap veteran. “It’s been six years,” he says, “and I’ve been in the game longer than that.” His relentless humor has undoubtedly contributed to his longevity and reinforced his willingness to work through life itself. He’s been working diligently, constantly, for the better part of a decade, and, somehow, he’s still flying his starship just under the radar.

That is to say, Curry isn’t concerned with being the most-followed rapper on social media. He’s made it clear that he doesn’t give a shit about clout. While he’s committed to calling out his contemporaries, that doesn’t mean he feels like they’re his responsibility. “I’m not tryna save nobody,” he says, laughing. “I’m just saying real shit. I’m not tryna save no one. I just hope my music helps, and I hope the message that’s behind it helps people, you feel me?”

So Curry is fully focused on evolving into an artist who will leave a lasting impact on rap, which means he’s always thinking about his next move. “I still gotta make another magnum opus,” he says. “Just gotta make that one album, and then have that one song that makes the album. I wanna win Grammys off my album. I just wanna be able to do what I gotta do.”