Part of the thrill of a new Beyoncé project—be it album, film, visual album, commercial, photoshoot, whatever—is seeing who she enlisted to help bring her vision to life. For the better part of a decade, at least, anything Beyoncé presents to the world has an air of par excellence. And to maintain that level of quality, she enlists an always exciting group of driven individuals to contribute. Sometimes she culls peak output from unexpected sources, other times she taps creators who may be unexpected choices for an A-lister like her to reach out to given her rolodex, but nonetheless are the right people for the job.

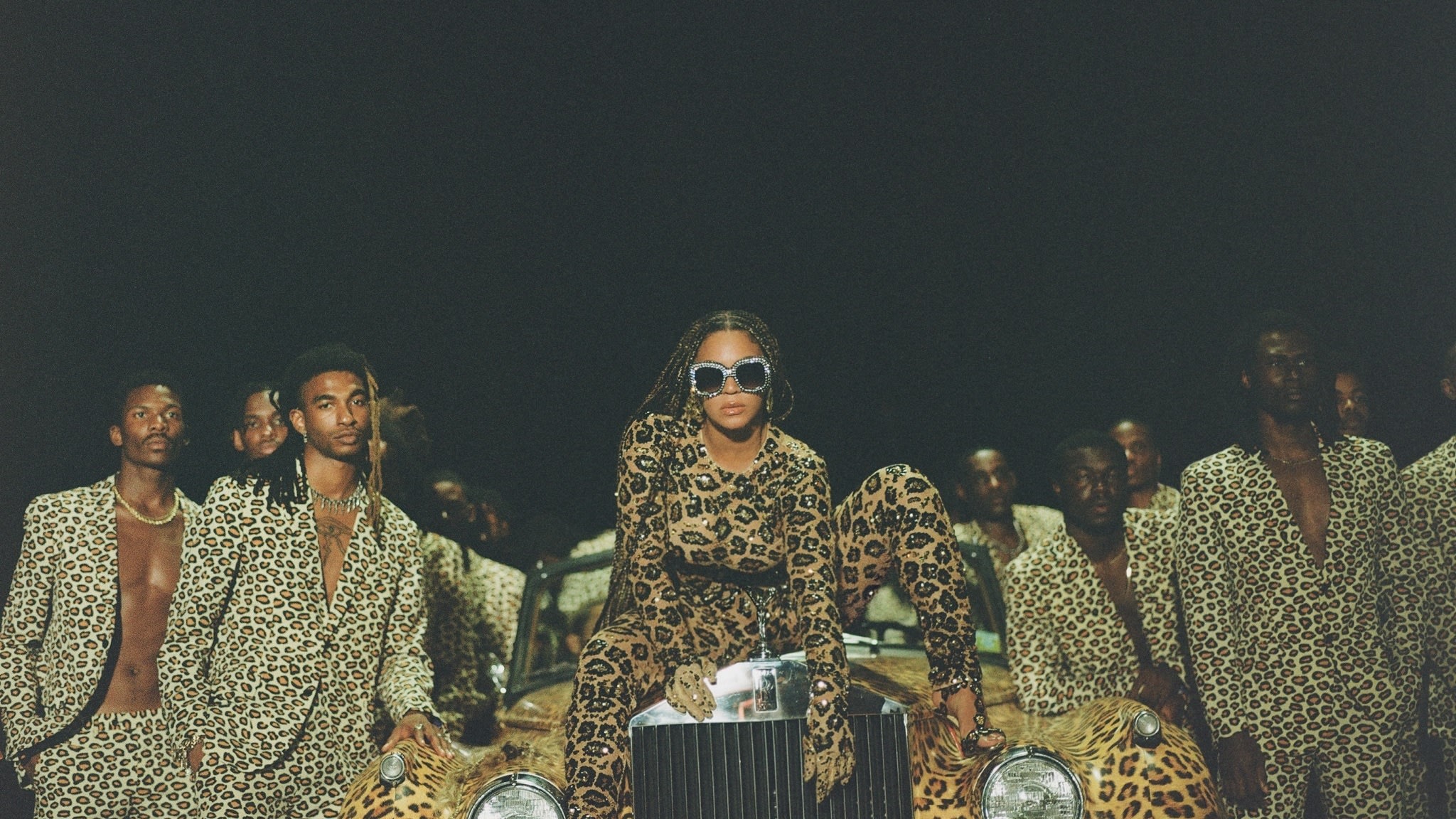

For a project like Black Is King, which seeks to refashion the Lion King narrative into a tale that makes its African roots and influences plain, contributors of African descent were obviously paramount—that goes for artists featured on the accompanying album The Gift as well as the crew behind the camera. Someone like Ibra Ake seems like a no-brainer, even if the production didn't find itself in Lagos for several key sequences. Ake, a Nigerian American, has been in the mix on some of your favorite pop culture moments of the past few years—as Donald Glover's Creative Director, he has a big hand in Atlanta as well as Glover's other standalone endeavors like Guava Island and "This Is America," which netted Ake a Grammy award.

His connection to Beyoncé and Black Is King didn't come through Glover though, rather it was his longtime friendship with her own Creative Director, Kwasi Fordjour (CDs connect), that led to the latter consulting Ake for some brainstorming before bringing him aboard for an official capacity. Ake's contributions to the film include the videos for "Water" (featuring Pharrell and Salatiel) and "Keys to the Kingdom" with Tiwa Savage and Mr. Eazi. Complex caught up with Ake to talk abut bringing Beyoncé's vision to life, how he as a Nigerian American approached the material and what he sought to infuse it with, the subsequent criticism following the film's release, and any updates on the long-awaited third season of Atlanta.

Congrats on Black Is King, It's truly a beautiful film even just visually speaking

Thank you very much, man. Yeah, it's definitely maybe the most beautiful thing I've had the privilege to work on. There's a lot of pretty imagery in there. I didn't really get to see the final cut fully until it aired.

Oh, wow, so you're watching it with the rest of us.

I was surprised. I've seen some of it, but there was still a lot of nice surprises for me that was just amazing.

How'd you get involved with the project overall?

I've been friends with Kwasi [Fordjour, Beyoncé's Creative Director] for a while and we've worked together on smaller things in the past, but not really a deep project before and he gave me a call. I think I was in the Atlanta writer's room at the time and he wanted me to kind of help write some treatments and run some ideas by him and just look at some of the [story]boards they were doing and it just grew from there.

I was really excited to do this as a Nigerian American. A lot of what I needed to do was go to Lagos and support the piece, especially for the "Water"-"Brown Skin Girl"-"Keys to the Kingdom" section. It was a lot of just hitting me up last minute and we started chatting and looking at boards and next thing you know, I was off to Nigeria to shoot some stuff.

Was it a situation where you listened to the music and chose what songs spoke to you the most and that's how you ended up directing certain clips or did your contributions just kind of happen to fall where they did?

He approached me with certain songs and I wrote a couple of treatments and it was all like nothing was too rigid. It's hard to describe. A lot of it was just us trying to work around artists' schedules—who was available as a director at that given moment based on who was available in front of the camera. So, there were all [of] these moving parts where there were some treatments that were approved that ended up not happening, but I don't know; it was a weird experience, but it was a lot of fluidity. What was impressive was—I think I worked on a lot of connected pieces—but it was impressive just how well people were able to do their own thing and still have this be a cohesive project. At least it was cohesive to me when I watched it and seeing everything connect.

Beyoncé is obviously the common denominator connecting all those different strands. How was it collaborating with her in terms of her imparting her vision, but then giving you the space to go and pursue yours?

It was a really great experience just to have the support from her in terms of resources and the attention it was going to be given because there's so much great work that is made out there that doesn't really get distribution. And another thing was just how respectful she was. I wish all directors and producers of culturally-sensitive material treated it with a level of seriousness that she did. There were so many conversations about what things meant. If it appeared in the shot, she wanted the meaning of what it meant, the history of it, even if it's like a mural, she wanted to know who painted it. I've never produced something and had to also be an archeologist at the same time.

There were a lot of days where I was like, "Oh yeah, I've never really thought about, even though that's part of my culture, I've never really thought about the actual history of what that means." And so, that lent itself to a lot of cool conversations and a lot of really cool moments. We were discussing cultural appropriation and I sent her clips of a Nollywood movie that is named after her. There were just like a lot of just weird conversations that were bouncing around during the project that led to certain choices being made. I really enjoyed all the questions she would ask me, because a lot of them I didn't really have an answer to. It's just some of those things where it's part of your culture, part of your life, but you're like why am I drawn to this? Why am I attracted to this? Like, what does this mean to me? Or what does this mean to other people in my life or other people with my identity, things like that. So, that was probably the most interesting part about collaborating with her, how much she wanted to know and understand. I've never really had a director or producer just be such a scholar. And even still, she was telling me that she had learned about other people and places and things making this project.

Wow. You mentioned earlier about how important working on and even just seeing this project was to you as a Nigerian American. How important was it that she presented this kind of re-framing of such a popular story that has African roots? Like, casting people like Donald in the [Jon Favreau re-imagining] was one thing, but it feels like this is more crucial, culturally.

Yeah, no, definitely. I really appreciate it and I think getting our stories funded on a certain scale and distributed is just so difficult and Lion King is probably one of the first properties that as a kid who grew up in Nigeria felt like—I mean, we have African cinema, don't get me wrong, but it was kind of the first big deal that felt like it was telling an African story or, one of the better kind of Western African stories. We still have this thing where we weren't really seeing what they were talking about. We're seeing just a drawing of what they were trying to talk about and I don't know, [Black Is King] felt like the real version to me, in a way, of the story that maybe people weren't ready for [before.] I guess this felt like the real Lion King.

One of the sequences you directed is "Keys to the Kingdom," which she doesn't really appear in. It underlines how the scope of the project is way bigger than just being a Beyoncé thing.

Definitely. I think in a lot of ways to me, at least, she felt like the Greek Chorus, explaining what you're looking at in the whole piece. Obviously she's the center for a lot of it, but what was really nice about it was, as much magnetism as she has, she was able to step away and just let, especially for that part, let the piece breathe, especially coming off of "Brown Skin Girl."

And yea, for that portion, I didn't want it too fantastical. I wanted that feeling of seeing stuff that you could recognize and visit and grounding it in an African location where you could clock where you were and keep that slow energy a little bit. I love the National Theater, the architecture there. Even just seeing the statues—so much discussion about statues is happening right now and I remember being on set last year and looking at all these statutes. Like a statue of a black woman with a child wrapped on her back, just seeing that as a black man, coming from America, I'm like, yeah this is opposite of what I have to inspire me growing up. You just don't get to see representation like that or black people honored in that way. And even just the architecture of that space—it feels like people don't really recognize that about the continent and I just wanted something that was impressive but wasn't fantastical, being like, no, this is real, this isn't Wakanda. This isn't what you're used to seeing. This is just us existing. And it does look amazing and fantastical and this is Africa also.

Even with all of the cultural research that Beyoncé did herself and cultivated from the collaborators like yourself, it is still getting criticism in some places. Was that something that you guys anticipated and have you grappled with it since?

Yeah, I think that is something we anticipate. I feel like that's the point of making art and I think a lot of art and celebrity is just kind of like a stadium for discussion. I try to make stuff that ages well. I don't really think about how it's going to do in the present and when it comes out. I'm just like, is this strong enough to be referenced x amount of years from now or revisited? But the criticism is just a lack of vocabulary around understanding Africa, around understanding blackness. A lot of the criticism is really not about criticism, it's really about the fact that we haven't really had a hub to have discussions about black identity, pan African identity, Afrofuturism, black authorship.

There's just all these terms and vocabulary that we don't even know. A lot of music writers, even music writers that are black, don't even use the technical terms when covering black art, for example, or African art. You know what I mean? Afrobeat is different from Afrobeats, which is different from Afropop. And just really, a lot of this work is just setting the playground for us to vote on what our opinions are.

So, I think if there's not a discussion, if there's not criticism, if there aren't questions that are leading to more learning and answering a discussion, I think you've made an uninteresting piece of work. And so, that's how I take it because, really, I see the criticism, but really the criticism just seems like a conversation about how we want to move forward in terms of naming ourselves, identifying ourselves. It's just part of all the conversation about the terms of identity and how can we up what that discussion looks like? How can we update our vocabulary? I don't see it as criticism. I see it as a lot of people updating their vocabulary about us and the work in general.

Right. It's more just starting a discourse.

Yeah, definitely. If I asked many people about Africa or anything, there's just a lot of stuff people don't know or haven't had taken the time to kind of look up about us. So, this is not a piece of work I expect to be easily dissected or understood and this is just the first of many conversations. I can't wait to see what happens as a result of this. I'm still listening to podcasts about it. I'm really interested in what African-Americans think about, Africans outside of the continent think about it, and what Africans in the continent think about it, and it's just been great. And it's interesting what the emotional stakes have been to that discussion. Comparing that discussion about Black Is King that everyone's having now versus the discussion that they're having about the actual Lion King movie, I feel because you're seeing black bodies in there, it's actually a way more spirited discussion and a way more emotional piece in these ways, because it's not just the Lion King story, it's the discussion about our real culture on top of it.

With the pandemic going on, we've seen a lot of delays of beloved projects, but I think one of the delay that's hitting everybody hardest is Atlanta, just as we were finally about to see season three go into production. Any updates on the status of resuming all that?

Updates are: we are just waiting to get that to work. There's no real update [laughs], we're just at the mercy of nature. And also, even if we're ready, we still need other people to be ready. We need other actors to be ready. We're going to have actors outside of our production, so we really are relying on so many people to be ready just outside of us being ready to go back to work. So, it's probably going to be awhile. But on the plus side, a lot of the scripts are in order and I think a lot of the ideas we're working on really aren't interrupted or affected by everything that's happened. And I think a lot of the ideas we're working on were pretty radical and I don't think we're going to lose a step in terms of commenting on the world and white people in the world, especially in Season 3.

But yeah, we're just waiting, man. I don't know when we're going to get back, but a lot of the work has been done, a lot of the writing has been done. I think everyone is itching to get back to work, but again, we want to be responsible and these stories aren't going anywhere. Our actors and everyone on the crew are committed to making this happen. I can say for pretty much everyone on the crew, this is our favorite thing to work on. So, now that a lot of the writing has been done we're just waiting for the green light to get back to work so, yeah.