We take our brick and mortar streetwear stores for granted today. In an age where hundreds of online retailers exist, customers seldomly visit an actual shop. Instead, they discover new brands on Instagram and purchase by hitting a checkout button on an e-commerce platform. Streetwear is mainstream, and its sense of community and culture is harder to find at a local shop.

But long before teenagers began buying Supreme off resale sites like StockX and Grailed, there were local establishments responsible for introducing streetwear to certain regions, before the term streetwear even existed. Places like Walter’s in Atlanta, which has been open since 1952 and serviced rappers and locals with fly sneakers and Adidas tracksuits, or Universal Madness in Washington, D.C., which was one of the first black-owned urbanwear brands and boutiques.

And then smaller brands like Fuct, Pervert, Triple 5 Soul, and X-Large emerged, but you couldn’t get them at Macy’s, so you’d have to shop stores like Union in New York City, Animal Farm in Miami, and Behind The Post Office in San Diego.

Post the ‘90s, the streetwear movement only became bigger with stores like Ubiq in Philadelphia, Brooklyn Projects in Los Angeles, and The Tipping Point in Houston. Some of these stores are still open, others have closed, but they all helped streetwear become what it is today.

Complex identified the pioneering streetwear stores in the U.S., and spoke to the founders about their influence on the market.

CNCPTS

Store: CNCPTS

City: Boston

Founder: Tarek Hassan

Year opened: 1996

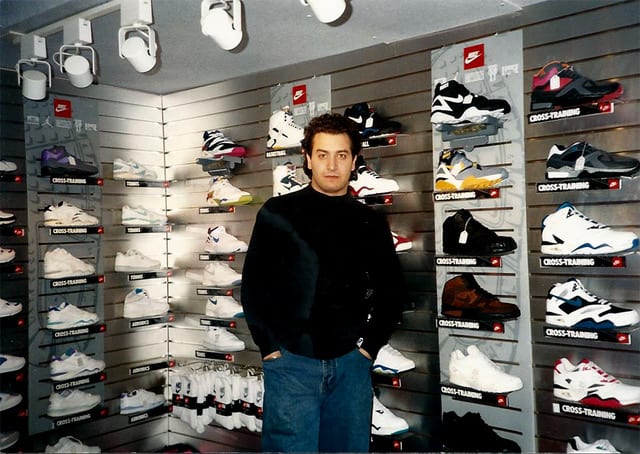

When Concepts was founded in 1996 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, it was no more than a passion project for Tarek Hassan. The boutique is now world-renowned, but it started out as a small section in the back of the Tannery, a now-defunct, family-owned retail chain that focused on more traditional footwear and menswear apparel. Concepts was a way for Hassan to show customers the snowboarding and skateboarding subcultures he was so interested in.

Deon Point, Concepts’ creative director, has been with the company full-time since 2006. But his relationship started as a customer years prior. While working in the construction industry in the Boston area, Concepts became Point’s go-to destination for limited edition sneakers.

“I remember walking through [the Tannery] and I was like, ‘What the fuck is this.’ Nobody knew what the hell I was talking about and then you got to the back and there was [the store manager Spungie] and these guys and it was just such a weird setup,” says Point. “They had snowboards and skateboards but then they had “Year of the Horse” Air Forces 1, the very first Viotech Dunks when they dropped...I was just in heaven.”

Aside from their Nike Tier Zero account, which gave the shop some of the most limited sneaker releases of the era, Concepts was also one of the first accounts in the country to stock Nike SB when it kicked off back in 2002. The limited footwear shared space with premium denim and brands like Burton and DC to cater to the skate and snowboarding communities Hassan was inspired by.

“The things [Tarek] thought he could do were bigger than what made sense for his business. And I think I have the utmost respect for him in that regard,” says Point. “I think he's a visionary.”

Eventually, Point became a buyer in 2006. Around this time he started “aggressively pursuing” streetwear brands like Crooks and Castles and The Hundreds, which he discovered during a visit to the Magic tradeshow in Las Vegas—before they were revered names in the space.

Despite this new focus and being open for a decade, Concepts was getting overshadowed by a brand new Boston outpost, Bodega. The concept was unique. It was hidden in plain sight and disguised as a corner store, but behind a secret door that looked like a Snapple machine was hard-to-get Japanese brands and limited sneakers. Point says it was a wake up call that Concepts needed its own standalone location, which opened in 2008.

“We were a bit complacent,” Point tells Complex. “We thought everything was cool and we were coasting along, and then you had Bodega come out of nowhere and they just got all this noise. They just literally caught us off guard and I think what that did for us was inspire our competitive nature and woke us up across the board.”

Along with the retail floor, the new shop featured a lounge in the basement for certain clientele and close friends. A lot of Boston athletes like Kevin Garnett and David Ortiz would frequent the shop. Ongoing collaborations with heritage companies Arc’Teryx, Canada Goose, and Birkenstock have always been fan favorites along with an in-house line of T-shirts, hoodies, and accessories. But most people know Concepts for its impressive run of immersive sneaker collaborations like the “Blue Lobster” Nike SB Dunk Low, “Kennedy” New Balance 999, and more recently a handful of Nike Basketball work with Kyrie Irving, many of which include special packaging and custom store build outs that add to the storytelling experience.

Concepts was also one of the first boutiques really embracing luxury brands at the time, years before the worlds of streetwear and luxury were so close knit. The success of Gucci sneakers and belts led way for brands like Lanvin, Balenciaga, and eventually YSL, Comme des Garcons, and Visvim.

“We knew we wanted to do something unique and different before we have another Bodega or someone else come in and try to shake things up,” says Point. “Let's put the flag down and kind of own home base. But more importantly, let's show the world that while we're a little boutique based in Boston, we can still do some pretty substantial things.”

Nowadays Concepts, which received investment from Zappos in 2018 has locations in New York City, China, and Dubai. It also continues to stock the best that streetwear has to offer. It was the first independent stockist for John Elliott back in 2012. Other big names included Bape, Billionaire Boys Club, Stussy, and Human Made. With a newly-renovated Boston space coming in 2020, it is clear Concepts is still striving to stay at the forefront of lifestyle retail over three decades later.

“We’d like to be viewed as a timeless brand,” says Point. “We may have missed some trends here and there, but we did it for the sake of being true to who we are. So I would like to be recognized for that above all.”—Michael DeStefano

Union

Store: Union

City: New York

Founders: James Jebbia and Mary Ann Fusco

Year opened: 1989; Year closed: 2009

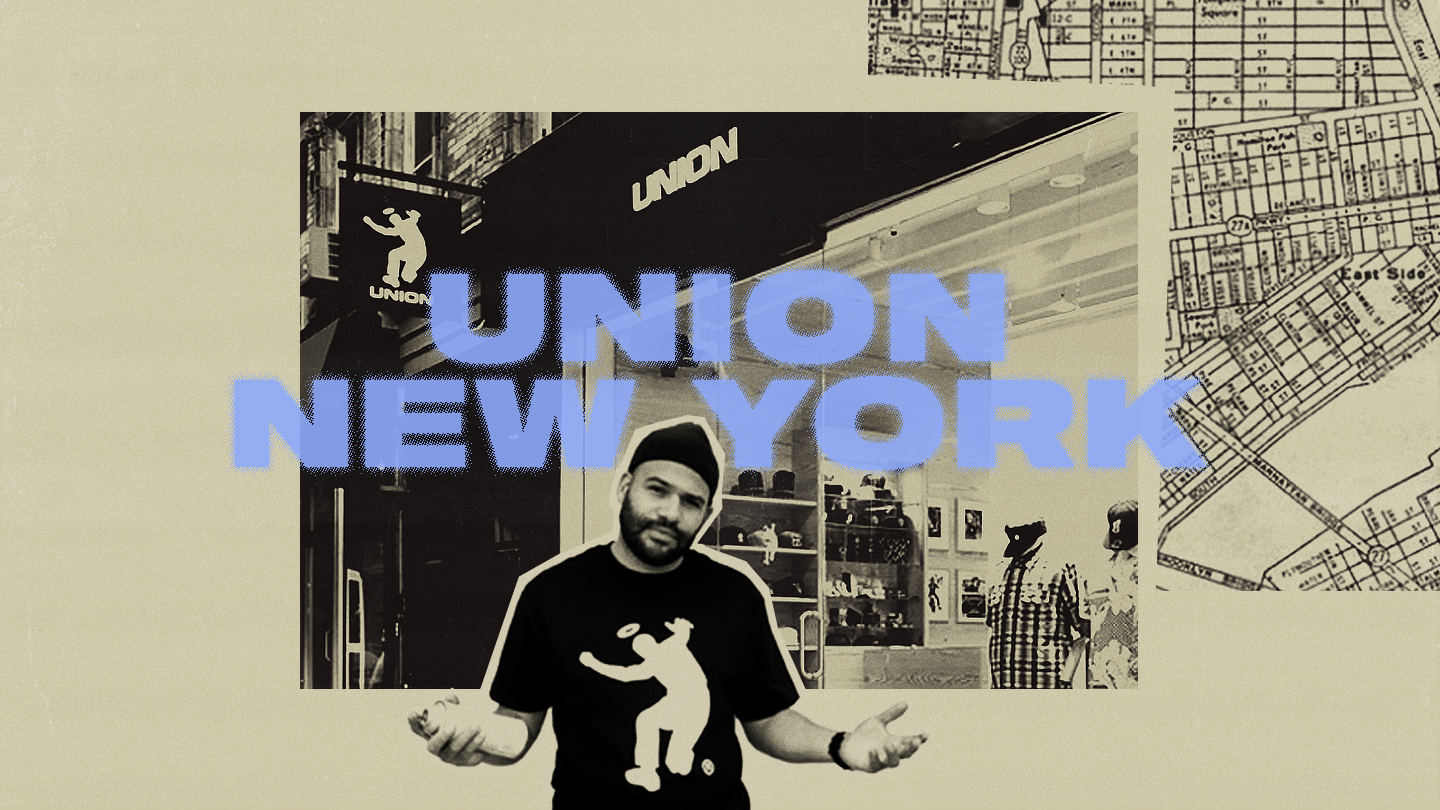

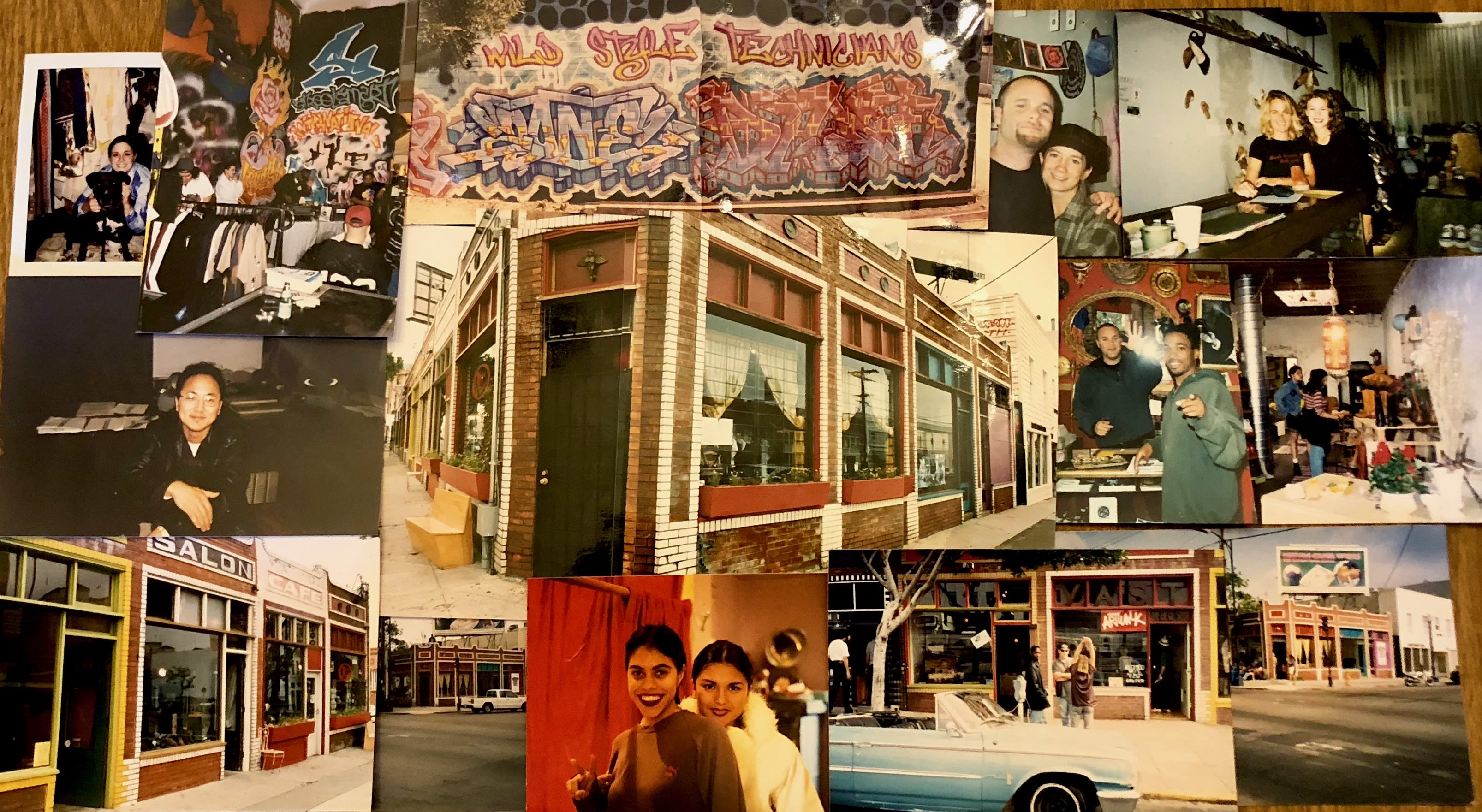

James Jebbia was a 29-year-old New York City transplant from England and working at Parachute, a high-end men’s clothing store in SoHo, when he started selling unique objects he curated with his girlfriend at the time, Mary Ann Fusco, at a flea market on Wooster Street. Eventually their table at the flea market got so busy that Jebbia quit his job at Parachute and pulled in another Parachute manager, Eddie Cruz, to work at the flea market full time. In 1989, Jebbia, Fusco, and Cruz took the concept of the flea market and brought it into a brick and mortar storefront on 172 Spring St. that they named Union.

“James always had a vision and he always talked about being successful. When he came to America he only had $1,000 in his pocket. But he always had schemes to make money,” says Jakuan Melendez, a former Parachute employee who became the manager of Union and is the founder of the pioneering art toy company, 360 Toy Group. “But if the trend went this way, James went the other way. Union was really the first streetwear, hip hop shop at the time. I don't know any brick and mortar shops that were like Union in 1989.”

Union was unlike the other neighboring mom and pop boutiques in SoHo at the time. They would blast Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet or display simple graphic T-shirts perfectly folded on a slanted wood board—Melendez says Fusco came up with this. Canvasses painted by Futura, Kostas Seremetis, Russell Karablin of SSUR, and KAWS served as art. And a local DJ named Ken Sport hustled hip hop sample mixtapes out of the shop. Although Union’s outpost on Spring Street wasn’t large enough to hold more than five people inside—employees had to make sure customers wouldn’t fall into the trap door on the ground that lead to Union’s stockroom—it carried a wide array of goods from all over. Boiled wool knit sweaters from Scotland were sold next to freshly printed Pervert T-shirts from Miami and Mackintosh raincoats from England. But Union treated everything, no matter its price point, with reverence.

“I remember touching the T-shirts, organically looking and being interested in seeing what they have, and then someone yelled ‘Yo! Don't touch the T-shirts! Let me know what you need,’" says Union Los Angeles owner Chris Gibbs, who first began working at Union’s New York store in 1996. “It kind of caught me off guard, so it was intimidating. Later on when I started working there, I took a lot of pride in being very gentle about trying to explain to people why they shouldn't touch the T-shirts.”

“James always had a vision and he always talked about being successful. When he came to America he only had $1,000 in his pocket. But he always had schemes to make money.”

-Jakuan Melendez, Former Manager of Union

Within five years of opening Union, Jebbia introduced Stussy’s first brick and mortar store on Prince Street in 1990 and Cruz, who co-founded Undefeated, went out to Los Angeles to open a combination Stussy/Union store in 1991. Jebbia opened Supreme on Lafayette Street in 1994. Artists like The Beastie Boys and Eric Clapton shopped at Union. Gibbs remembers Japanese tourists and local drug dealers frequenting the Spring Street shop. But despite going from a table at a flea market to having stores on both coasts, Union’s MO remained the same: To hustle and stock exclusive products that couldn’t be found anywhere else.

“A large criteria for us would be exclusiveness. Back then, to be carried in our shop was a big deal,” says Melendez. “Union, was like the equivalent of Supreme today. We were able to go to a brand and say ‘Hey, we want to carry you in our shop but you can't sell to anyone else in New York.’”

Union sold pieces from smaller designers like Project Dragon by Futura Stash and Bleu, SSUR, 10 Deep, and Hiroshi Fujiwara’s early brand Electric Cottage along with lines like Duffer of St. George or Maharishi. However, when the sneaker industry began growing in the early 2000’s, Union attempted to pivot towards that market. Gibbs moved to Los Angeles just a year after Cruz opened his sneaker store, Undefeated, in 2002. Although both Union stores became spots to cop limited edition sneakers, it was also the start of the store’s troubles.

“There's a million sneaker shops that you can go to to get all the limited edition sneakers and that really took the industry like crazy,” says Gibbs. “As the sneaker stores started growing, Union, as an apparel-based store, couldn't compete.”

By 2009, Union was struggling to stay afloat. The 2008 recession hit the streetwear industry hard and less shoppers were willing to spend money on streetwear. Cruz ended up selling the Los Angeles store to Gibbs in 2008. Gibbs says he was able to keep the Los Angeles store afloat by pivoting heavily towards Japanese brands like Visvim, WTAPS, and Neighborhood—brands Union had exclusives on in America. But, a year later Union New York shuttered its doors.

“I'm saying this more as kudos to the the founders, Mary Ann Fusco and James Jebbia, they [Union] was the first streetwear store in the world,” says Gibbs “There was no other store like it.”

—Lei Takanashi

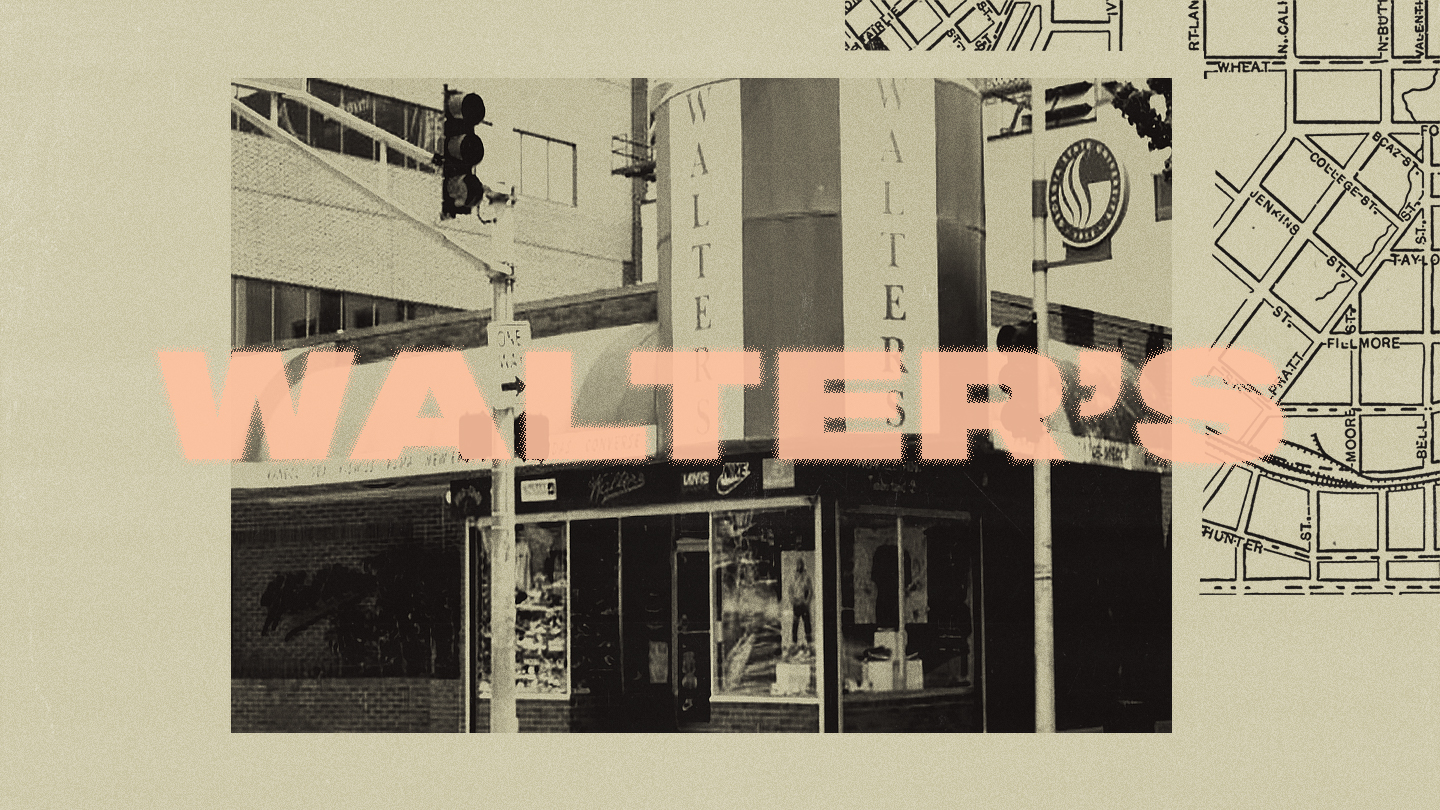

Walter's

Store: Walter’s

City: Atlanta

Founder: Walter Strauss

Year opened: 1952

Walter Strauss escaped from Nazi Germany in 1936 at the age of 13 when his parents sent him to live with another Jewish family in West Virginia. He eventually made his way down to Atlanta and worked in a shoe warehouse while saving up to purchase a space on Decatur Street, which used to be a bustling strip of saloons, theaters, and shops that were mostly owned by Jewish immigrants but serviced the African American middle class. But it underwent urban renewal around the 1940s and became a key area for Georgia State University, which has purchased most of the buildings on the strip over the years.

Shortly after buying and opening the spot in 1952, Strauss moved into a bigger space only a couple blocks away where Walter’s has been located for the past 60 plus years. He spent his first few decades selling workwear from brands like Dickies, athleticwear, and sneakers for men and boys, but by the 80s, thanks to an influx of money moving into black communities during the crack era, Walter’s, which was within walking distance from housing projects before they were destroyed, became the go-to for black locals wanting to dress fly.

“As the street money starts accumulating, the street guys want better street fashion,” says Leshaun Burke, who has worked at Walter’s for the past 25 years—he took a year long break but came back. Burke remembers Walter’s selling the $300 leather Adidas outfits, Eight-Ball leather jackets, Starter jackets, and Filas when they were aspirational at $150 a pair, which was expensive at the time.

Over the years Walter’s became known for its large sneaker selections that came in multiple colorways. Burke says for a while Walter’s was the only place in Atlanta where customers could buy Bo Jackson, Jordan and Andre Agassi sneakers and brands like Fubu, Maurice Malone, and Mecca.

Frank Cooke, who used to head up collaborations at Jordan Brand, went to college in Atlanta during the 2000s and remembers visiting the store as a student and watching people buy six or eight pairs of white Air Force 1s at a time. Patrick Morrison, who has handled the buying for Walter’s over the past 30 or so years, was from this culture, so he understood what the customer wanted.

“They kept it true,” says Cooke. “It was never, ‘Let’s try to get Off-White. It was just that cool, authentic street vibe.”

But Cooke says the staff, which was made up of the community the store served, is another reason for its loyal customers, which included celeberties like Killer Mike, Gucci Mane, Jeezy, Future, and Jermaine Dupri, who immortalized Walter’s in the “Welcome to Atlanta” video with Ludacris. Strauss and his wife Estelle hired employees through high school work programs, and they were known for treating everyone equally—for a while Walter’s was one of the only stores in downtown Atlanta that let black customers try on product. This sensibility trickled down to his team, which put a high value on service and connecting with the customer.

“It's almost like a barber shop,” says Burke. “We tell people, ‘Man we shoe salesmen and we are psychiatrists.’ We’ve done everything in there. We’ve even talked people out of situations.”

Strauss passed at 94 in 2018. The business is currently owned by his ex son-in-law, Jeff Steinbook, who runs the store with his two sons and employees who have been on staff for over 30 years. Not much has changed inside the store, but Atlanta and its retail scene has evolved with competitors like Social Status and Wish entering the market. Walter’s lost its status as the top Nike account in Atlanta, but Burke says not having the hype, fairweather customer has helped the business better serve its repeat shoppers. Cooke believes the store still deserves those high energy drops.

“That's one of those places where it may not be the most designed out build out and they have boxes stacked to the ceiling, but they don't get the proper releases they should,” says Cooke. “Releases are in places where we aren’t. We have to have a chance to get releases at retail prices as well. We like Sacais and high end sneakers, too. It doesn't always have to be in a well designed store. It's the soul. It’s that immeasurable variable. You can’t pay for that type of sauce.”

—Aria Hughes

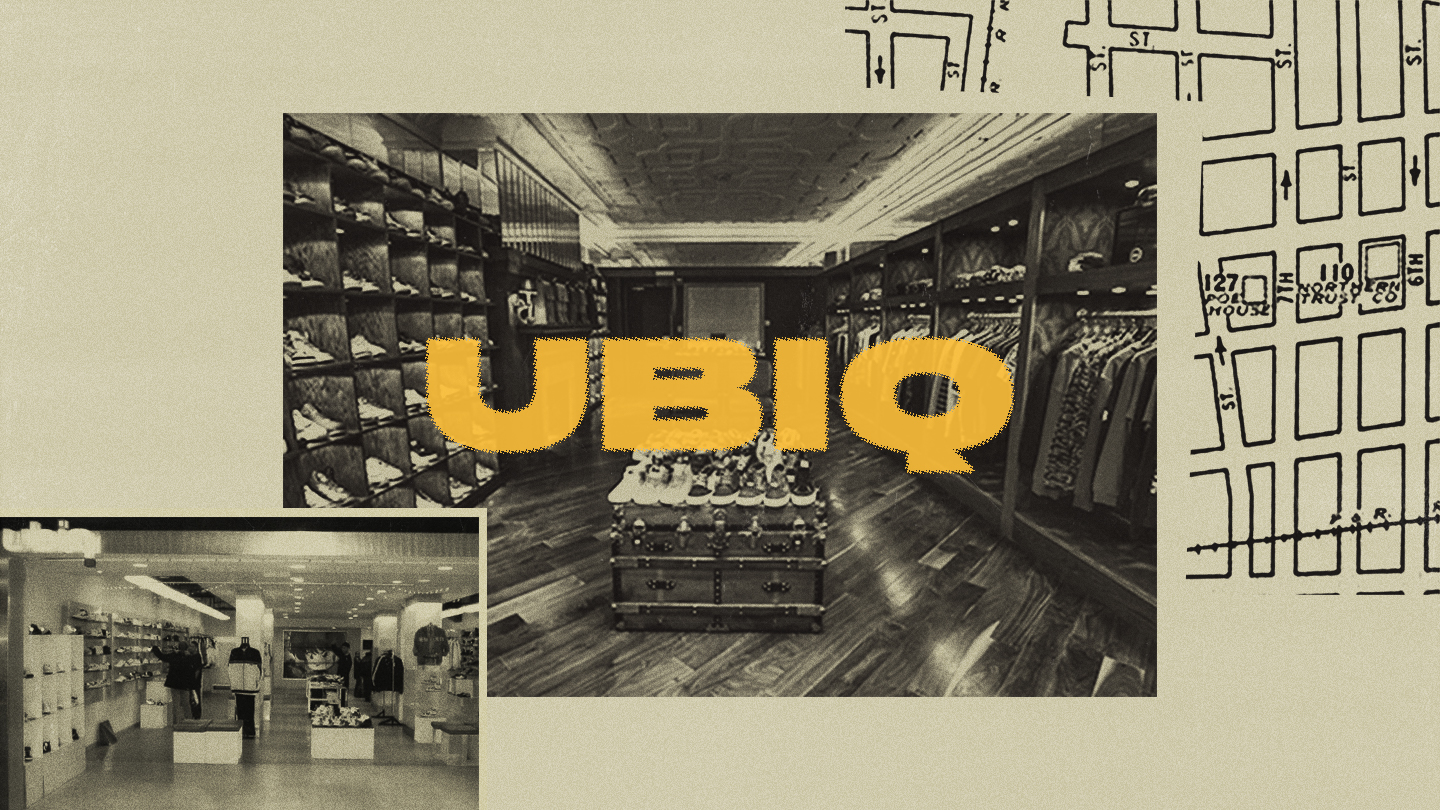

Ubiq

Store: Ubiq

City: Philadelphia

Founder: John Lee

Year opened: 2002

When you think of streetwear hubs, Philadelphia is probably not the city that comes to mind. That isn’t necessarily for a lack of a community either. The City of Brotherly Love currently boasts an impressive lineup of boutiques like Lapstone and Hammer and Pusha T’s Creme 321, and more niche menswear offerings like Ps and Qs. Unfortunately, a lot of the shops that helped grow the community during its boom in the late 2000s have not been fortunate enough to keep the lights on. But Ubiq has been able to survive.

John Lee founded the boutique back in 2002. It was housed in the popular Gallery mall on Market Street, an area that has since been closed and converted into a new shopping center, and served streetwear to the city long before it was the norm. With the help of Mason Warner, who would go on to open his own, now-defunct shop WTHN in 2006, Ubiq struck deals to carry brands like The Hundreds, Nike SB, and Levi’s Vintage before many other spots in the city.

Lee’s interest in the business actually began in 1993 at Samsun, a Philadelphia sneaker store owned by his father-in-law. Through this job, he would meet Atmos founder Hommyo Hidefumi. Lee’s travels to Japan inspired him to bring the retail concept stateside, more specifically to Philly.

“[The Gallery] was the busiest center of commerce at the time. I paid a lot of money to get the lease because I didn't have the credit that I needed to get into the mall,” says Lee. “There was not much marketing. The design was minimalistic, very futuristic. When we first opened, people were literally running to our store because they didn't know what to make of it. They'd never seen a sneaker store like that before.”

Its unique take on retail made Ubiq a hot spot in the city. Exclusive Nike sneakers and hard-to-find Japanese brands like WTAPS and Neighborhood populated the shelves. At one point, Ubiq even stocked Supreme, although the decision to wholesale the brand was a short-lived one for the streetwear giant. Pharrell and his ICECREAM skate team were know to stop by. One of its members and local skater, Jimmy Gorecki, even worked at the shop briefly in its infancy.

“It speaks volumes about Ubiq. We're one of the pioneering stores and because of our location, we didn't get a lot of recognition for what we did and what we brought to the market. But we're proud to be part of Philadelphia and we're going to continue to support the city.”

“We had a lot of cool kids come through, watched how they grew up, and became very relevant players in our industry. That kind of excites me. When we opened the Ubiq in the Gallery and Walnut, it changed the landscape of the retail in Philadelphia."

—Jason Lee, Founder of Ubiq

In 2006, Lee opened up a second Ubiq location near Rittenhouse Square on Walnut Street, an area known for its more premium shopping experience.

“We were looking for a Madison Avenue type of location in Philadelphia, and Walnut Street fit the description. That's the highest end retail street in Philadelphia. We loved the building, just old, retro looking, and we just wanted to build something beautiful.”

Still stationed there to this day, the Walnut Street location is where Ubiq would really make its mark on Philly’s streetwear scene. A space dedicated to throwback sports purveyor Mitchell and Ness occupied the second floor for a number of years. Stussy even operated a Chapter store there although it did not last very long. If the first floor was where customers could find the latest limited shoes and streetwear, the second floor was Ubiq’s experimental space. Lee says the goal was to create the “Fred Segal of Philadelphia.”

Its projects over the years have included work with Undefeated, Stussy, Nike, and New Era. Guests have included everyone from local legends like Questlove and Meek Mill and the Clipse and Travis Scott. Nowadays, Ubiq operates two locations in Philly and Georgetown in Washington, D.C.

“We had a lot of cool kids come through, watched how they grew up, and became very relevant players in our industry. That kind of excites me. When we opened the Ubiq in the Gallery and Walnut, it changed the landscape of the retail in Philadelphia. So that's exciting as a business person,” says Lee. “For the longest it was just a Ubiq. Now there's Lapstone and Hammer, Ps and Qs, I just want to generate more excitement for Philadelphia. We have so much talent in Philadelphia.”—Michael DeStefano

Tipping Point

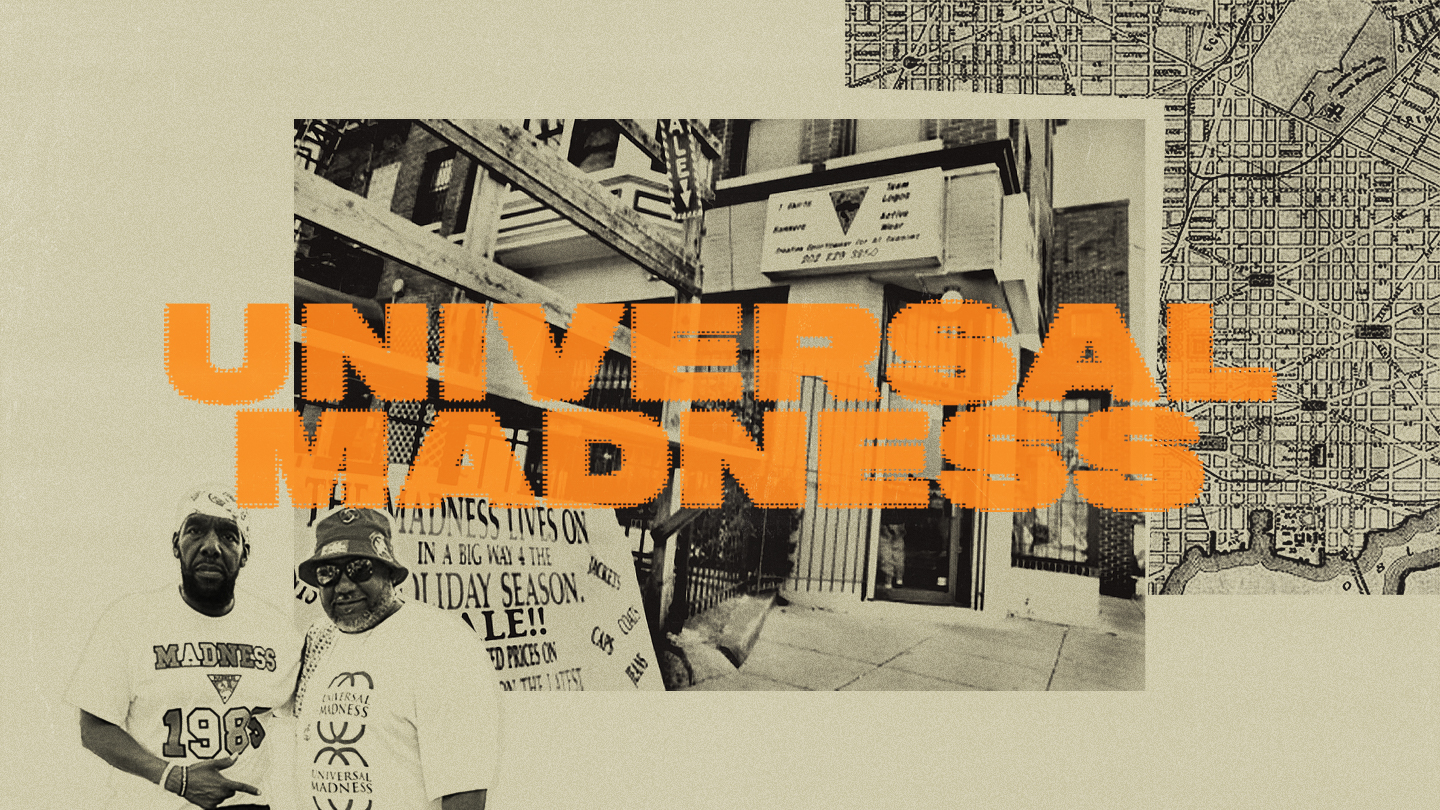

Universal Madness

Store: Universal Madness

City: Washington, D.C.

Founders: Eddie Van; Tyrone Johnson

Year opened: 1983; Year closed: 2010

In 1983 Eddie Van and Tyrone Johnson opened a beauty and barber supply store at 3119 Georgia Avenue in Northwest Washington, D.C, close to Howard University’s campus, that also used to sell T-shirts. The T-shirts started selling more than the beauty supplies, and in 1985 they decided to focus on apparel, calling the first iteration of the clothing business Madness Connection.

“My main interest was current events,” says Van. “If it was hot, we had it. We created our own characters that were geared toward the hot record or current event at the time.”

Van put out a Madness T-shirt emblazoned with “Fuck tha Police,” which was inspired by the NWA song, but its connection to D.C.’s go-go culture made Madness Connection a staple for Washingtonians. In 1989, popular go-go band Experience Unlimited, best known as EU, wore Madness hats and T-shirts in the “Da Butt” video, which became one of go-gos first crossover hits—they performed the song in Spike Lee’s School Daze movie released in 1988. Madness Connection also sold a lot of T-shirts covered with SMUG, which was an acronym for Summer Madness Urban Gear, which Backyard Band, a popular D.C. go-go group, would reference during performances.

“We had Backyard Band, Chuck Brown, and EU and everyone being the face of the line. They were marketing it,” says Chloe Chada Van, Van’s daughter who calls Madness one of the first black-owned urbanwear or streetwear lines. “So there was a trickle down effect and people from the metropolitan area started to wear it.”

Madness was known for its multi-colored, woven letters and triangle logo. Van says most of the graphics were created by local youth. Another big part of the business was its customization service that was inspired by Dapper Dan and Danny Hogg, the late D.C.-based grafitti artist better known as Cool Disco Dan. Customers could walk in, buy a Madness Connection T-shirt, and select whatever letters and numbers they wanted and it would be complete in 30 minutes. Customizing the shirts turned the pieces into status symbols, they started at $40 and could go up to $300.

“It wasn't cheap. So if you were able to put together a whole entire outfit to wear to a go-go or special event and customize it, that meant you had some money,” says Kevin “Scooty” Hallums, co-founder of streetwear brand Diet Starts Monday.

The store itself was a gathering spot for the well-to-do locals and professional athletes, and it became a stop for celebrities visiting the Nation’s Capital. Van says artists including Puffy, Biggy, Juvenline, and Jermaine Dupri would come in the store to buy Madness pieces—in 1995 they moved across the street at 3120 Georgia Avenue to a bigger space. Chada says Madness’ operations inspired Russell Simmons and Puffy to introduce their own clothing brands—Chada would go on to work for Bad Boy for nine years. But locals were also influenced by Madness. Other D.C.-based brands like Shooters, All Daz, Hobo, and We R One emerged and opened stores. Many of them adopted Madness’ multicolored aesthetic and they became a way to represent where you were from in D.C. Hallums says most people that wore Hobo were from the south side of the city, while Madness and We Are One were for people from the north.

At its height, Madness operated its flagship, another shop in Southeast, D.C., and a warehouse where people could by Madness for discounted prices. But things started to change in 1996 when Van plead guilty to selling crack to a Drug Encorcement Administration informer out of his store between 1989 and 1994. He was sentenced to nine years in prison.

“Eddie was a street legend,” says Kenny Burns, music industry executive and personality. “And for him to be out there, visible like that and to have that presence, it was a phenomenon. It added to the appeal of the brand. There was a time he was away and it was still popping, but when he went away, that feeling also went away.”

Things were also changing in D.C. Gentrification was happening and natives were being priced out and moving to Maryland or Virginia, and with the rise of celebrity driven streetwear lines, and the internet, people no longer looked to the local go-go artist as the star they wanted to emulate. Chada says Madness was also late to e-commerce—they just launched a couple years ago—which made it hard for people outside of D.C. to purchase the clothes. In 2010 they shut down the store, but with help from Chada, they have relaunched, are holding pop-ups throughout the city, and opened a store in Waldorf, Maryland, which is 45 minutes outside of Washington, D.C.

The revival of Madness coencides with a push to preserve D.C. culture. Last year residents started a “Don’t Mute D.C.” movement after non-natives complained about go-go being played outside of a Metro PCS store. This has led to newer D.C.-based streetwear brands like The Museum and E.A.T. who Hallums hopes will carry the torch.

“Madness is one of the brands that's been able to stand the test of time, but that wasn't the case for everybody,” says Hallums. “It’s extremely hard to run local D.C. brands with the influence of the Internet and gentrification. So it’s up to these brands to preserve the culture. Madness is so important. It was our Gucci. It was our Prada. It was our Hermes.” —Aria Hughes

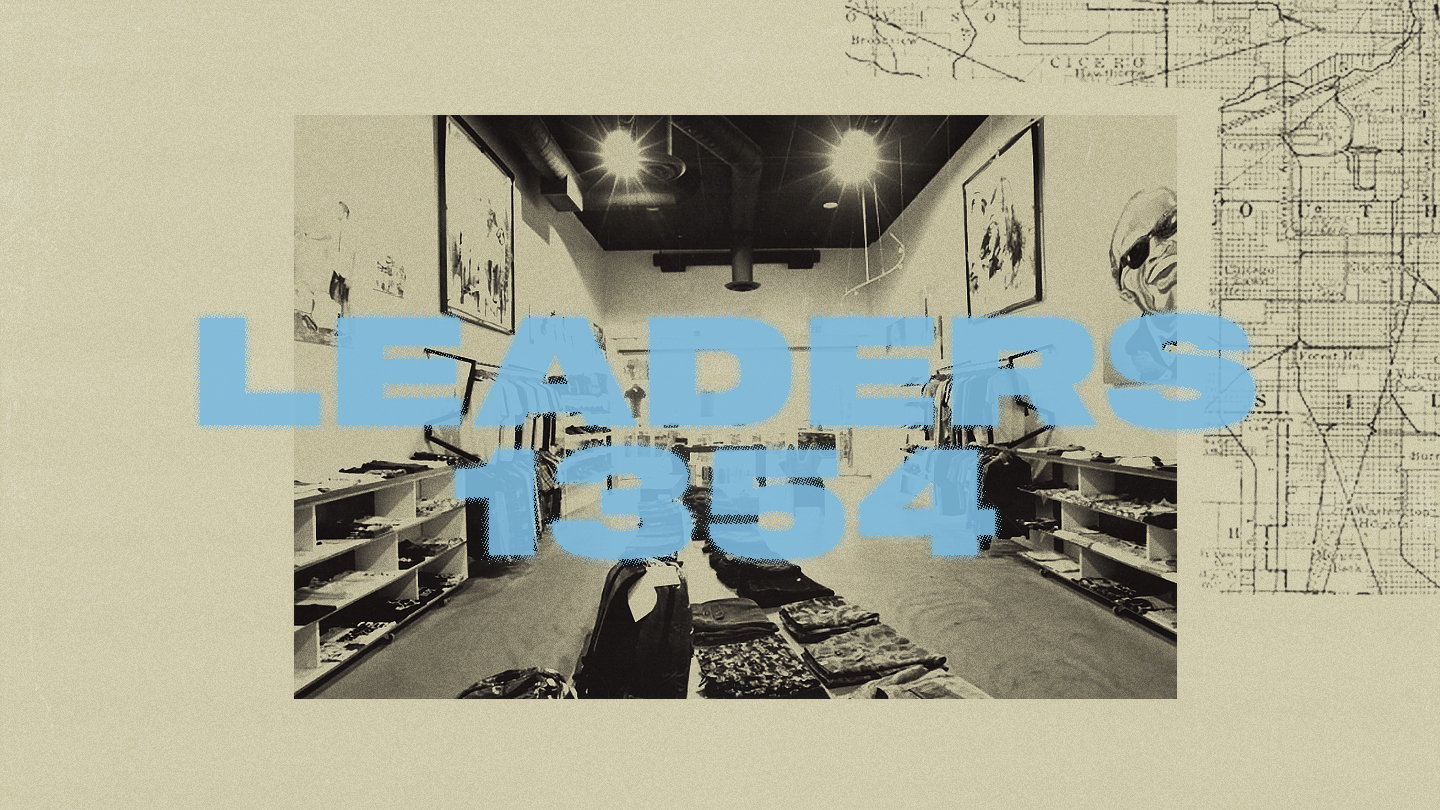

Leaders 1354

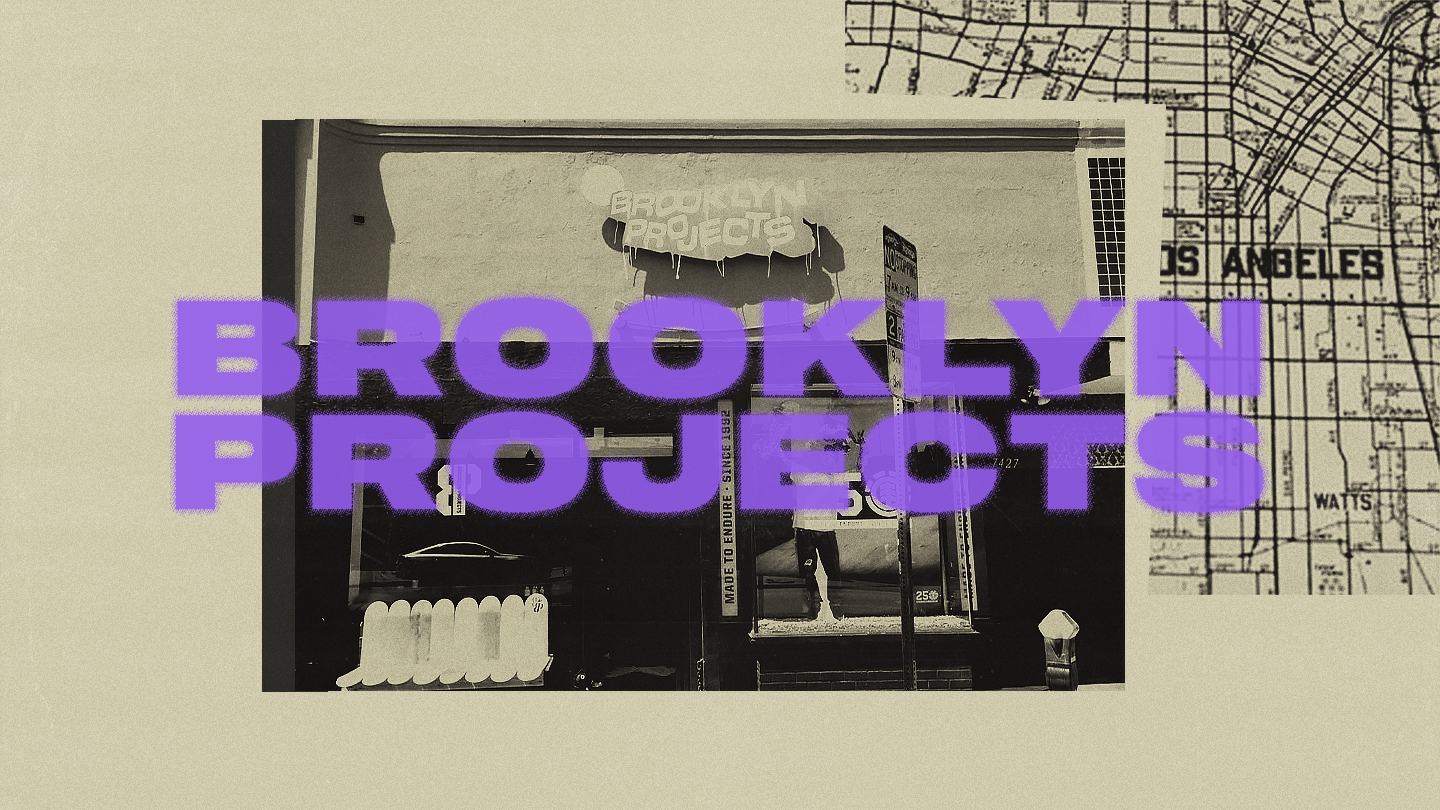

Brooklyn Projects

Store: Brooklyn Projects

City: Los Angeles

Founders: Dominick Deluca

Year opened: 2002

Before Dominick Deluca entered streetwear, he was in the music industry. As an Assistant Manager for Rush Artist Management from 1988 to 1992, he toured with metal band Anthrax and helped orchestrate Shawn Stussy’s first collab, a collection of friends and family merch for the Public Enemy and Anthrax Bring the Noise tour in 1991 and 1992. He moved on to become an A&R in 1992 for EMI Music before becoming a veejay on MTV's Headbangers Ball later the same year.

Streetwear was still a very niche community, but Deluca wearing brands like X-Large, Fuct, and Stussy on air during the show led to companies sending him free boxes of product. “I stood out and I loved it. Eventually, my dressing room was just like a storage room,” says Deluca.

In 1992, to get rid of his excess clothes, he would open a flea market space at the Caesar's Bay Bazaar in Brooklyn. Because of the heavy foot traffic at the flea market, in 1993 he moved to a larger space, the Brooklyn House skate shop, which was located near Marine Park. It sold brands like Haze, Pervert, and Ecko in its early days. By 1996, Deluca made his way to Los Angeles working for Island Def Jam as an A&R once again, but Brooklyn House was his passion project.

“I just loved it so much. I never made money from it. I paid my bills for the most part, but I just loved it, loved being a part of a new movement and just meeting like-minded people,” he says.

Deluca says there was no scene in LA at the time other than a shop called Atomic Garage on Melrose that used to backdoor stuff to Japan. The Brooklyn House in LA initially had a problem stocking certain brands due to its proximity to Atomic Garage, but was still able to carry names like Haze, Pervert, and Project Dragon. By 1999, Deluca made the choice to permanently stay in Los Angeles. He named the shop to Brooklyn Projects, which would officially open on Melrose Avenue across from the original Brooklyn House location in 2002. It remained there until the lease was up in 2009. It’s been at its current location on Melrose since 2010.

“Melrose has always been the epicenter of fashion, music, and culture. Before there was Fairfax, before there was La Brea, there was Melrose. It's almost like opening up on Broadway in the Lower East Side or opening up on Lafayette [in New York City]. It has a certain thing about it, so Melrose has always been a destination,” says Deluca. “I've had opportunities to open on Fairfax when it first started, before Supreme even opened up. But I was like, ‘Nah, I want to be where I am. I want to be my own island. I don't want to play in the same sandbox as other people.’”

"If there was no Brooklyn Projects, there would be no Fairfax, period. [James Jebbia] went five blocks away from me, opened up Supreme, and started a whole movement, but it was because of the seeds that I planted. I should get a royalty."

—Dominick Deluca, Founder of Brooklyn Projects

Deluca says the look of the original space in 2002 was inspired by shops he visited in Japan, more minimalistic with displays that treated the items like art rather than just product on racks. His store mixed street brands of the time like Freshjive and Recon with more high-end names like True Religion and Paper Denim, a precursor of sorts for the melding of both worlds that has become so commonplace in fashion today.

Brooklyn Projects was also a cultural hub for the West Coast skate community, holding events for Chad Muska’s Muskabeatz and photographer Atiba Jefferson. At the same time, the shop was giving a platform to younger brands in Los Angeles like The Hundreds and Diamond Supply. Deluca even held the first release party for Pharrell and NIGO’s Billionaire Boys Club line back in 2006. Over the years celebrities including Michael Jackson, Tom Cruise, and Vin Diesel all shopped there at one point. The shop is probably best known for its four Nike SB collaborations that included the “Reign in Blood” Dunk High inspired by Slayer, and “Walk of Fame” Dunk Low.

“You wanted to be in Brooklyn Projects because at the time, there was no Fairfax. If there was no Brooklyn Projects, there would be no Fairfax, period,” Deluca tells Complex. “[James Jebbia] went five blocks away from me, opened up Supreme, and started a whole movement, but it was because of the seeds that I planted. I should get a royalty. I'm kind of like the Ray J of the streetwear scene. How Ray J put Kim Kardashian on the map with his porno and really broke her? Well, I'm Ray J and Supreme is my Kim Kardashian. I helped them. Fairfax is my Kim Kardashian. If it wasn't for me, it wouldn't have happened. That's a fact.”

Despite the widespread impact that Deluca and his shop have had, he hasn’t been treated to the same level of mainstream success as some of his contemporaries.

“If I could take it all back, then I would go back in time 15 or 20 years, and a certain few that I helped out, I would not help out and I can pretty much guarantee that they would not be in a place they are now because I gave them the tools. I helped lift them up the mountain and now I'm down here going, ‘Hey, I'm still down here,’” Deluca says. “We were first along the way of a lot of things that we don't really get credit for because it's overshadowed by other things.”—Michael DeStefano

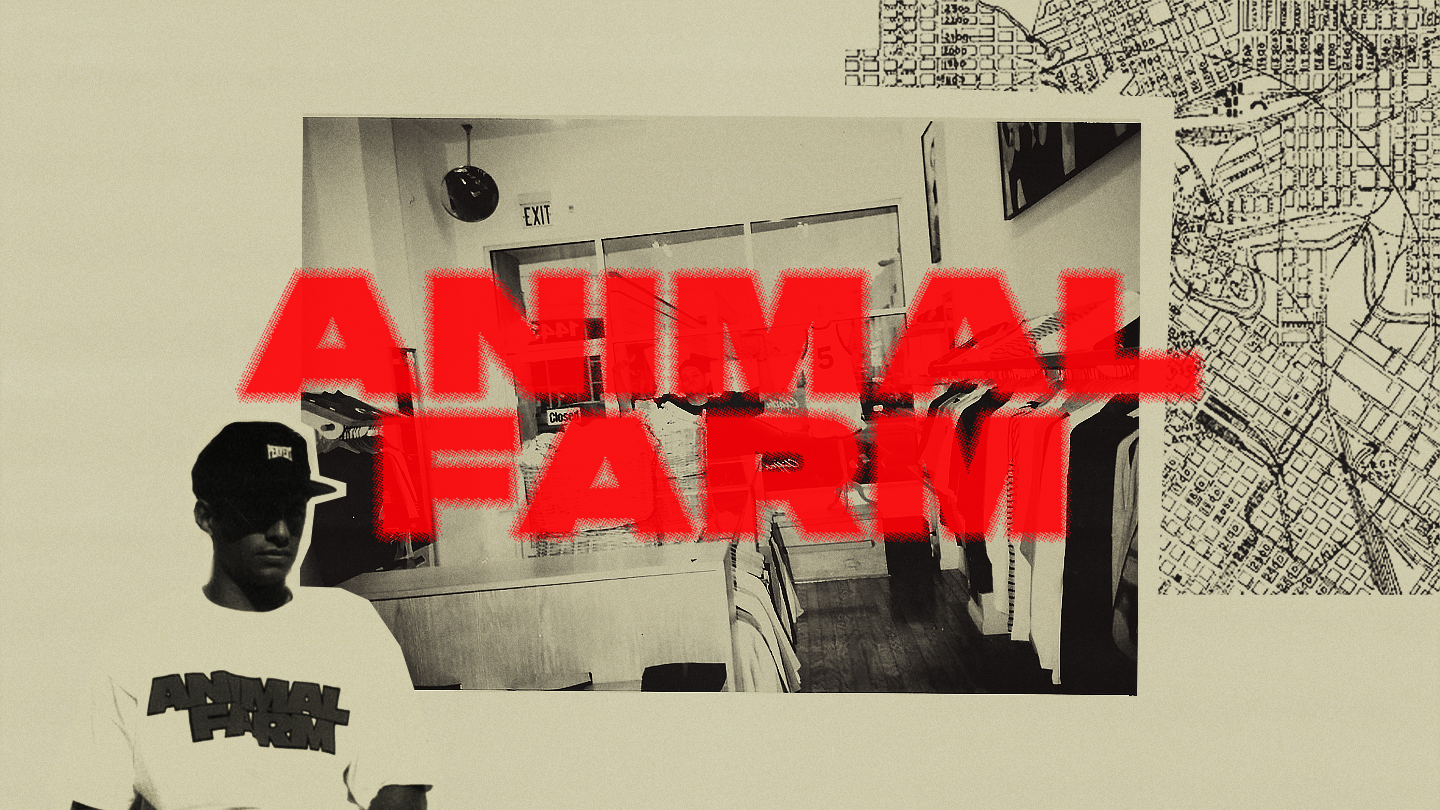

Animal Farm

Store: Animal Farm

City: Miami

Founder: Don Busweiler

Year opened: 1990; Year closed: 2000

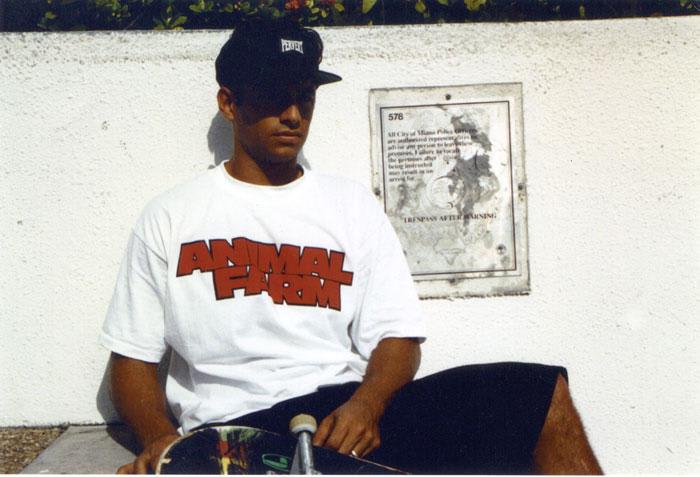

Don Busweiler moved to Miami Beach in 1989 to attend art school. As a high school student, he garnered a local following in New York on Long Island for screenprinting the word “Pervert” onto T-shirts—Busweiller wanted to see if he could take the word’s negative connotation away by turning it into a clothing brand. He wanted to continue his brand in Miami and open an eclectic store that was similar to Union in downtown Manhattan. So he convinced Todd Glaser, the store’s original financer, who is a prominent Miami real estate developer today, to put up $10,000 to open Animal Farm on 1443 Collins Avenue in 1990.

Animal Farm was open from noon to midnight, located just across the street from the popular Warsaw nightclub, and always had a DJ spinning two Technic 1200 turntables. Aside from stocking the freshest gear from brands like Fresh Jive, X-Large, Fuct, Two Black Guys, and Triple Five Soul, Animal Farm became a clubhouse for skateboarders, BMX bikers, ravers, and members of Miami Beach’s hip hop scene.

“There were a couple of surf and tourist shops, but there was no dedicated streetwear store. Animal Farm was the first one,” says Geoff Heath, a veteran streetwear graphic designer who worked for Supreme in the late ’90s and started his career at Pervert and Animal Farm. “Within Miami and Miami Beach, Pervert was the hometown streetwear brand that was popular.”

By 1995, Animal Farm and Pervert were booming. Pervert was sold globally and worn by celebs like the Beastie Boys and Janet Jackson—she wore a Pervert shirt to the 1995 MTV Video Music Awards, a look that was later copied by Givenchy. Jimmy George, one of the original founders of the skateboard brand Alien Workshop and the skateboard distribution company Cow Skates, invested in it. Busweiler even opened a standalone Pervert shop to sell extra stock a couple of blocks away. But then, suddenly, at the age of 25, Busweiler abandoned it all.

He met a religious cult passing through Miami known as the “Brethren,” a nomadic group of Christians who cut off their ties to mainstream civilization in exchange for salvation. Busweiler left his possessions, family, and friends behind to join the cult, despite his coworkers’ attempts to dissuade him.

Pervert and Animal Farm’s leftover employees attempted to keep the brand and the shop alive. However, due to disagreements with the business partners who owned the brand, the original Pervert team split. Former employees like Heath and Brendon Babenzian moved to New York City to work for Supreme. Animal Farm closed around 2000, and Pervert was laid to rest in the late ’90s. Busweiler, however, is still making clothes.

“Don stopped by Miami Beach last year and he designs all the clothes for his people,” says DJ Tom LaRoc, a childhood friend of Busweiler who helped get Pervert clothing on rappers in artists relations for Pervert. “We had a debate about herb and I was on a roll. They’re not with ganja and they couldn’t get a word in, edgewise. So the next day Don dropped off this art before he left and it reads, ‘Ain’t no high like the most high.’ He's still a modern-day typography artist.” —Lei Takanashi

Behind the Post Office

Store: Behind the Post Office

City: San Diego

Founder: Micheal Pringle

Year opened: 1991; Year closed: 1997

In 1991, Micheal Pringle, 22, discovered an abandoned ground-floor, all-brick building in downtown San Diego. At the time, the area surrounding that building on 801 F Street was so desolate that the 1,800-square-foot space Pringle found was actually being used by crack dealers. But what Pringle saw was a great business opportunity in a city that coincidentally became ground zero for the burgeoning underground streetwear scene.

In 1981, San Diego became home to the Action Sports Retailer (ASR) trade show, a twice-annual event where surf and skate brands like Vans and Quiksilver set up booths to sell products to store buyers. But by the early ’90s, young entrepreneurs like Pringle began penetrating the show with hip hop- and street-inspired clothing brands. At a 1991 ASR show, Pringle racked up $150,000 in orders for his clothing brand Stoopid. With that money, he signed a 10-year lease on that space he came across and named it after its location, “Behind the Post Office.”

Behind the Post Office became a popular destination for the city’s local hip hop community—Bay Area legend Del the Funky Homosapien even performed there. Because of its success, after a year, it expanded to San Francisco, with a location on Haight Street. Both stores were stocked with brands like Fuct, Pervert, Fresh Jive, Tribal Gear, Conart, and Triple 5 Soul that struggled to fit in at ASR, since it wasn't welcoming to younger lines with hip hop influences. So Pringle decided to launch his own trade show, 432F, which he ran in tandem with Behind the Post Office from 1993-1995.

Although 432F only lasted a short time, it gave spaces to pioneering streetwear brands such as Not From Concentrate by Futura and Stash, Kingpin NYC by Bleu Valdemir, OBEY by Shepard Fairey, and Ecko by Marc Ecko. Before shows like Agenda, 432F was the first trade show truly dedicated to streetwear during the movement’s most formative years.

“It wasn't like anyone had any idea of what they were going to do,” says Scott Nelson, the founder of the streetwear brand MANKIND who also helped design Pervert’s booth at 432F with the brand’s founder Don Busweiller. “You found out about these things globally through word of mouth. When you got there, everyone was scrambling because people weren't making or designing booths ahead of time. They were getting there and ad-libbing.”

But after 1995, Pringle didn’t hold another 432F show because he felt it had run its course and he also lost interest in the streetwear business. Japanese buyers were visiting Behind the Post Office and cleaning out the store’s stock with $10,000 cash in hand, but it no longer interested Pringle. In 1997, he closed the San Diego store and moved to farmland in West Marin, California, where he still lives today.

“If it wasn't for that store, a lot of that culture probably wouldn't have happened,” says Grant Lau a professional artist who was formerly a graphic designer for Behind The Post Office. “We all had clothing brands making streetwear and we were all friends, so we all gathered together to try and do something.”—Lei Takanashi