The outbreak of COVID-19 and systemic racism have placed us squarely in front of two pandemics. Unrest has swarmed the country as people protest police brutality, racism, and oppression while simultaneously facing the uncertainty of the pandemic, including unemployment and trying to maintain optimal health and wellbeing. Black people have been disproportionately affected by both ongoing issues, with Black Americans being three times more likely to become infected with COVID-19 and twice as likely to die as their white counterparts. Additionally, Black Americans account for less than 13% of the U.S. population, but are twice as likely to be shot and killed by the police as white people, according to the Washington Post.

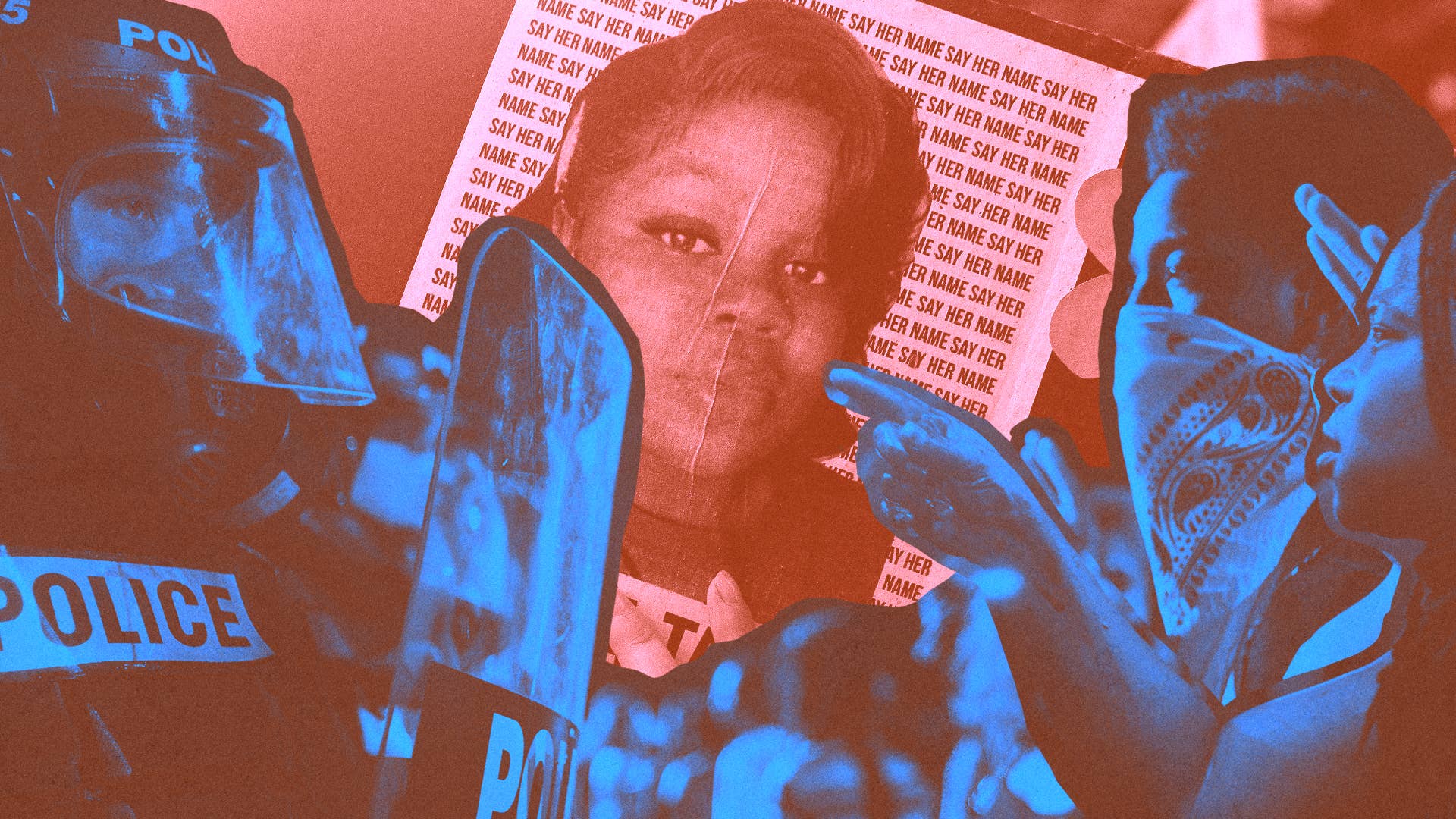

Breonna Taylor’s is among the growing list of Black men and women who have lost their lives to state-sanctioned violence carried out by police officers. A 26-year-old Black woman, Taylor always had a twinkle in her eye, a desire to help others as an essential worker, and had so much more life to live.

It has been 160 days since Breonna Taylor was murdered. An illegal no-knock warrant allowed her door to be kicked in by plainclothes police officers, her body to be riddled with bullets and left unattended, and her boyfriend, Kenneth Walker, to be arrested for shooting an officer as he tried to protect himself and Taylor. Despite continued public pressure to file criminal charges, nearly five months after Taylor's death, progress with her case has been slow and prosecutors are facing significant obstacles to bringing homicide-related charges against her killers. While they and the Kentucky Attorney General continued to live their lives, Louisville Metro Police Chief Rob Schroeder and Chief of Public Safety Amy Hess walked out of a city hearing on Monday, August 3, without testifying amid an investigation into the mishandling of Taylor’s death, according to Fox News.

Whenever it’s Black women who are the victims of police violence or any kind of state-sanctioned violence, I think there is outrage there, but it usually comes mostly from other Black women." - Danielle Scruggs

Further examination of what happened on that night points to a redevelopment plan, better defined as gentrification, that marks homes in the area as hotspots for drugs and violent crime. According to documents filed by the Taylor family’s lawyer, the detectives who murdered Taylor were deliberately misled as a part of the redevelopment initiative. “Redevelopment plans” in minority neighborhoods typically involve pushing out the current community, moving in an influx of white people, and “improving” the area while marking up the cost of living—another reality Black people face. This is an effort that some white people have taken into their own hands. In Valley Stream, New York, Jennifer McLeggan, a Black woman, mother, and nurse, has faced continuous harassment and intimidation tactics from her white neighbors in an effort to get her to move—thus resulting in Anthony Heron, a Black man, vowing to protect McLeggan and her daughter from sundown to sunrise.

Breonna Taylor, however, isn’t the first Black woman to be executed while sleeping and relaxing in her home, nor is she the first Black woman essential worker to be assaulted by police. In 2019, Neomi Bennett, a Black woman and nurse, was stopped and detained for a search for tinted windows , in which the officer accused her of having stolen property in her car and threatened to smash her windows. She was charged with obstruction, which she later successfully appealed.

During the pandemic, health care workers have been praised for putting their lives on the line to help us and our loved ones. They’ve been deemed heroes, and they are. People have made noise about their protection and receiving proper PPEs to do their jobs. Ironically, Breonna Taylor was an EMT and ER technician, yet because she is a Black woman who lost her life to state-sanctioned violence, she isn’t deemed worthy of the same protection and outrage. April Reign, an activist and the creator of #OscarsSoWhite, says your occupation and status shouldn’t determine your quality of life. “The person on the wrong side of the law or the golden angel, it doesn’t matter. These are people with real lives, families, and friends, and when we connect those intimate moments to our own families, it makes the pain that much worse,” she says.

In 2010, 7-year-old Aiyana Stanley-Jones was set on fire by a flash-bang grenade and suffered a gunshot wound as she slept on a couch with her grandmother, an incident in which charges against officer Joseph Weekley were dismissed. In 2019, Atatiana Jefferson was shot through the window of her home by ex-officer Aaron Dean after an evening of playing video games with her nephew. Both instances sparked protests seeking accountability and justice, but over time the noise seemed to settle.

Reign says we don’t go up for Black women as we do for Black men. “We didn’t protest for Sandra Bland and Atatiana Jefferson the way we should have,” she explains. In efforts to keep Breonna Taylor’s name trending and her story at the fore, people have organized on and off the ground, but the growing trend of memeifying her death on social media platforms, including TikTok and Twitter, has dehumanized her and used comedic gimmicks to grab people’s attention. “It’s been interesting to see how people want to be involved and how people have mobilized. But there’s a fine line that we walk all the time with being respectful and wanting to put her name out there. However, we have to keep her centered whenever we do. Society has an increasingly short attention span, to the point people can’t stick around for conversations,” says Reign. Over the years, the consistent slaughtering of Black women and men, combined with social media, has birthed numerous initiatives to amplify their stories and seek justice, but they have looked much different.

After the death of Sandra Bland, the hashtag #IfIDieInPoliceCustody trended on Twitter, with people calling out the perils Black people experience under threat of law enforcement. And after the death of Eric Garner, “I Can’t Breathe” shirts became popular, but still nothing like the TikTok dances and cheesy tweets that end with, “But arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor.” Additionally, these movements have continued to evolve as the novel coronavirus has ripped through the Black community, affecting people who work job deemed essential but pay them an unliveable wage. According to Vox, Deatric Edie, a mother and fast food worker, worked three jobs during the pandemic to try to make ends meet and take care of her family—only making $9 an hour as a shift leader at McDonald’s. Edie, who is high risk due to diabetes and high blood pressure, eventually tested positive for COVID-19 after not being provided with proper PPE by McDonald’s. She was left to quarantine without paid leave from her three jobs, including at Wendy’s and Papa John’s. Experiences like Edie’s align the fight of essential workers—especially Black ones—with the fight against racism and systemic oppression, as both serve as a death sentence the powers that be ignore.

Taylor’s death was followed by the deaths of Tony McDade, a Black trans man, and George Floyd, inciting protests and unrest nationally and globally. But the onset of outrage was mostly in light of Floyd, who was killed by police officer Derek Chauvin, who kneeled on Floyd’s neck for eight minutes and forty-five seconds. Ultimately, the four officers involved were charged—although Thomas Lane, J. Alexander Kueng, and Tou Thao have since posted bail and are free to live and casually buy essential Oreos until their tentative trial date of March 8, 2021. Unfortunately, Black women and the Black LGBTQ+ community have been an afterthought in the movement for justice, and it must stop. “Whenever it’s Black women who are the victims of police violence or any kind of state-sanctioned violence, I think there is outrage there, but it usually comes mostly from other Black women, not the community in general. I notice this especially happens with Black trans women as well, and it’s really an epidemic,” says writer and photographer Danielle Scruggs. The outrage surrounding the murder of Black trans women like Dominique “Rem’mie” Fells and Riah Milton looms in the shadows of Black Lives Matter, even though they experience racial injustice and oppression, as well as transphobia.

"We didn’t protest for Sandra Bland and Atatiana Jefferson the way we should have." - April Reign

Unlike George Floyd’s case, not much has changed since March 13—when Sergeant John Mattingly, Detective Myles Cosgrove, and Detective Brett Hankison entered Taylor’s home shortly after midnight as part of a drug raid, although the suspect and his accomplices were already in custody. Charges have yet to be brought against the officers responsible for her death, although other performative measures have been taken, such as the enacting of “Breonna’s Law,” an ordinance that bans no-knock warrants in Jefferson County and requires officers to wear body cameras while serving a warrant. Louisville’s police chief and chief of public services recently walked out of a government oversight committee meeting about Taylor's death, further adding to the discussion to defund the police. Additionally, all cameras must be turned on at least five minutes prior to executing the warrant. While the no-knock ban has the potential to stop this from happening again, that would only be possible if police officers followed orders and faced real consequences for their actions. While this seemingly actionable step is being taken to protect Black people against state-sanctioned violence, there also need to be mandates in place to further to protect them from a virus they are increasingly impacted by, which is something Donald Trump refuses to do.

Stories like those of Breonna Taylor, Atatiana Jefferson, Sandra Bland, Korryn Gaines, Aiyana Stanely-Jones, Dominique “Rem’mie” Fells, Riah Milton, and Jennifer McLeggan speak to what it means to truly protect Black women, to amplify their stories the same way we do those of Black men—every day, without gimmick, and with continuous noise even when the dust seemingly settles after they feed us performative justice that feels like enough to silence us.

Keep being loud for them.