Marc Ecko is finally comfortable with nostalgia.

He has a lot to look back on. His clothing brand Ecko Unltd. dominated the late ‘90s and early aughts. Its signature rhino logo even made it into cultural touchstones like the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade and the Madden video game franchise (Ecko himself played quarterback on Team Ecko). He’s also the reason Complex exists. He founded the media company in 2002.

“Some people unplug nostalgia. They think there’s almost like a weakness in that or something. I’ve said it myself. You have to go on to what's next,” says Ecko. “I'm OK with reflecting on that now. I think I feel more comfortable in my skin reflecting on that.”

In 2023, Ecko is far removed from the streetwear brand that he built from the ground up. He sold the interests in his namesake label in 2009 and left Complex in 2023. Now he focuses on philanthropy through the nonprofit XQ Institute. But Ecko has decided to get back into the lab one more time.

To celebrate the 30th anniversary of his namesake label, the brand tapped him to design a capsule collection titled “Dear1993.Art.” Comprised of items like OG rhino logo T-shirts and hoodies with colorful graffiti embroidery, it was Ecko’s love letter to the year where it all started for him. Each item from the 13-piece collection will be limited to 93 units, signed and individually numbered.

“Each item was very improvisational. I literally was sitting with some of my archive elements, my old black book. I was using that as a source of inspiration and thinking about those days at Rutgers starting the business and airbrushing T-shirts,” says Ecko. “It’s such a different part of my career. It was very nostalgic.”

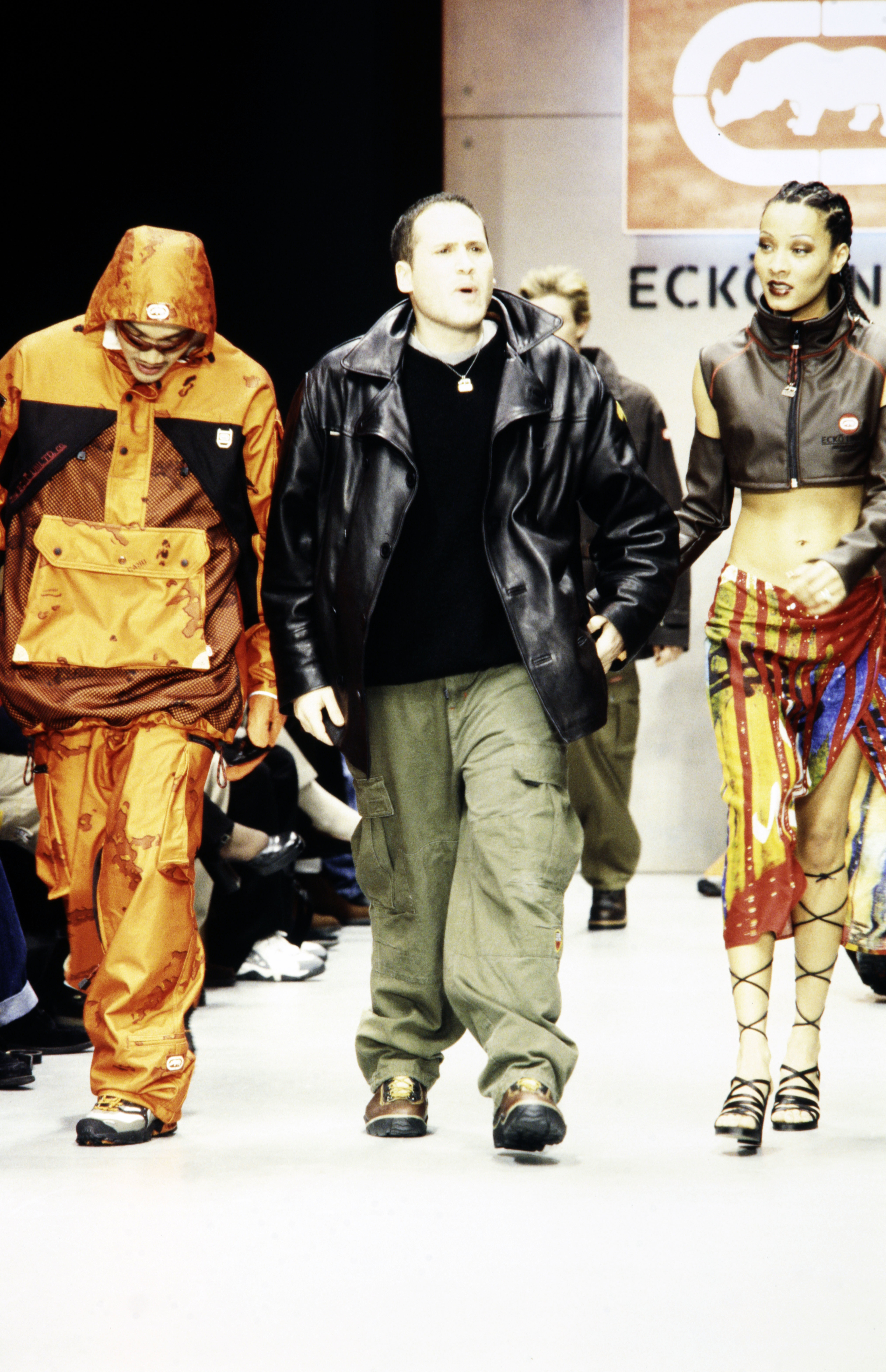

To mark the launch, Ecko is also hosting a VIP pop-up in Los Angeles on Nov. 16 that highlights various elements of the brand’s archive from long-lost sample designs to prototypes from the brand’s runway shows in the 2000s.

Ahead of the release, we got a chance to sit down with Ecko over Zoom to discuss it all, from his cult-classic Getting Up video game to his thoughts on the current state of streetwear.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This capsule celebrates the 30th anniversary of your brand. I know you're not involved in the day to day anymore, but to see something you built from the ground up be able to celebrate a milestone like that, how does that feel?

It’s very rewarding. I was a little reluctant. The folks who own the brand have been kind of soliciting me since the 25th anniversary. I've always had a little bit of apprehension or tentativeness because those kinds of milestones can be really self-important, or not necessarily as important to the customer as they are to the brand internally.

Folks that operate some of the marketing and licensing were people that have been with me for pretty much the whole ride. They're still around. So the strength of a personal bond with some of those folks and the fact that they gave me the space to do it in a way where I could frame it as a love letter to the year 1993, the inception year, [were why I did the project].

I wanted to do it very, very limited, 93 pieces of each item. I didn't want to overthink it. I didn't have time. I have a full-time job. So this had to be like a vocation, and the fact that they gave me the space to do it in that manner made sense.

I know a lot of people say they only look forward to what’s next. You were finally ready to look back.

Yeah. I think that I've operated in that mode my whole career. Anyone that knows me, knows my work, knows that I'm always moving ahead and working on what's next. So this was a little bit different. I didn't realize the intensity and fandom among some of these really hardcore vintage collectors. They're the ones that really turned me. They gave me a different view with such interesting stories from all over the country. Many of them were really authentic, early supporters of the brand. Without them, it would have never happened.

The capsule is you looking back on 1993. Can you talk about putting the collection together and some of the details we see?

Each item was very improvisational. I literally was sitting with some of my archive elements, my old black book. I was using that as a source of inspiration and thinking about those days at Rutgers starting the business and airbrushing T-shirts.

I thought about those initial materials, and then I thought about the satisfaction I get with embroidery and appliqué. I'm an illustrator. I'm an artist. I wanted to approach it through that medium. So I did a piece called Prayer Warrior. I did a piece called Still Loud, which was based on some early freelance work I did for Epic Records of this boombox. They asked me to do a logo. This is before I even designed the rhino. I was a freelance graphic designer doing that kind of work. There’s the first Ecko tag logo, which was a nod to the Phillie Blunt logo and the Krylon spray cans. The brand was spelled with an H from ‘93 to ‘95. It was reliving some of that. It’s such a different part of my career. It was very nostalgic.

You haven’t worn the design hat for a number of years. Is it like riding a bike? Once you got back into it, did it just feel natural to you?

I don't want to say it's unfinished business. I don't feel unresolved. But I definitely like the feedback loop of designing and making really complicated productions like I used to. Every day was like Christmas. Every day you’d get that FedEx package or DHL package and the prototype would come in. It would be all wrong and you’d have to fix it. You asked for one thing, but you meant another. You were either happy or you were pissed. It was like an engineering feat as much as a design feat.

Some people unplug nostalgia. They think there’s almost like a weakness in that or something. I’ve said it myself. You have to go on to what's next. I actually think it's important to realize that you're only as tall as the people's shoulders that have held you up. I think it's important to reflect on a composite of all that work. It's not really a singular creative expression. It’s about all of that, that body of work that was contouring and shaping our perception of beauty of what fashion was. I'm OK with reflecting on that now. I think I feel more comfortable in my skin reflecting on that.

Is that the first time you've really looked back on the brand in this way?

Yeah. There's a purpose. It's about doing these art objects and really doing them for my friends. The majority of this stuff is going to my friend network, colleagues, collaborators, and artists I admire that I've worked with. Being able to have that moment and have the folks at the Ecko brand give me that space to do it that way—each piece is hand signed—I wanted to treat them like an art object. It's not about fashion anymore for me. I didn't approach this like it was a fashion exercise.

I have a job. I'm doing philanthropy. I'm working in complicated systems on education reform, on climate -elated issues, on cultural and justice-related issues. So this was like a vocation. This had to be extracurricular, and it had to be something that was built with a lot of love. So hopefully when people see it, they feel it. They just feel this love letter. I just wanted to make a love letter to 1993.

The brand was so big for so long. There's so much to look back on. Do you have a particular moment tied to the brand that sticks out to you when you look back on everything?

I think one of the most important moments of my career was not a singular moment. My career is made up of a lot of really catalytic events. I think what was interesting about Ecko compared to other brands is that we were kind of unrelenting. We were like that underdog punching above our weight class. I credit a lot of that confidence and affirmation and validation to Michael “MC Serch” Berrin. Serch was a very, very important part of the equation. I was a kid going to Rutgers University, still enrolled in the pharmacy school, airbrushing live at the Lyricist Lounge—shoutout to Danny Castro and Anthony Marshall. But MC Serch was like this superhero from my childhood that presented himself as a peer. He said, “I wanna help you. I believe in what you're doing.” Suddenly, I was in his orbit. Serch was very connected in the music industry. He was like an MC’s MC. He deserves a lot of flowers. Serch helped me reframe how I look at marketing. He was an advocate for me. So I give him a lot of props.

I’m 28. A lot of my memories tied to Ecko are you being the quarterback of Team Ecko on Madden or the Getting Up video game. I'm watching the X Games on ESPN and Mike Metzger is wearing an Ecko jersey. You were penetrating so many areas of culture in the 2000s. Do you look back on those moments as big wins for the brand, or do you feel like you were spreading the brand a bit too thin by that point?

I think I spread myself too thin. I think brands are fairly durable. The humans behind the brand, what's under the hood, is what matters. Brands are only as good as the actions of the stewards. I think those things helped the brand with differentiation. I also started Complex around that time, so it was a wild period in my life. I was in my 30s. They say do what you're good at in your 30s. I took that really literally and I went for it. But from a management point of view, could I have done things differently? Sure. Did it affect my ability to shepherd the brand in a more effective way to operate as effective as I could? Sure. But so did the financial crash. These things happen. I don't regret any of it. It’s my story. If it didn't happen that way, then Complex might not happen the way that it did. If Complex doesn’t happen in the way it happened, I might not be working in the field I'm in now. No regrets.

If you go back to 2007, the market was incredibly frothy. The markets crash. Anyone who is operating on deep credit, like most of the big retail brands were at the time, mine included, suddenly their inventory became a real risk. You're making money, but you're burning money because the cost of the business is getting increasingly harder and the banks are putting more constraints on you. It was hard, man. It was like an Ivy League education, better than Ivy League education. I know a lot of Ivy League people. They don't come close to having learned what I learned.

When you were dipping your toe into video games at that time, was your vision to really go all into that piece of the company? Did you envision sequels and growing that more?

Oh, absolutely. I’m very proud of that period because it’s incredibly difficult to launch original intellectual property in gaming. It's one of the hardest mediums to break through. And Getting Up was sort of a testament to slow and steady, working my way through the ranks of EA all the way up to [EA Chief Creative Officer] Bing [Gordon]. I kept myself in front of all those executives at Ubisoft and then eventually Atari. I had to get a dozen no’s to get one yes. And that's all I needed. I put my money where my mouth was. I prototyped the game. I paid for all the pre-visualization of the game. I was writing the script for Getting Up from 1998 to 2003.

A lot of people hit me all the time on social media about the game. I'm working on a film adaptation right now. Things that are good take time. They're hard to do. I'm not approaching things in this phase of my life with commercial pressure. It's got to be what's in my head.

But long story short, I definitely had a vision for Mark Ecko Entertainment. Now I'm much more content working on a very focused format and going narrow and deep. That's what I've learned over my creative career. I didn't have that in my 30s. It was wide and shallow. I could show you I could do all these things. I'm a multi-hyphenate. And if you look at what was happening within hip-hop culture at the time, there was this mogul thing that was a part of the extreme sport of being at the top of your game. You can't be boxed in. You have to be unlimited. Eventually, you realize that constraints are actually good. Constraints drive better creative execution. But I don't regret trying all those different things. I learned a lot.

Taking it back to the clothing, the trend cycle is sort of hitting that time where Ecko was in its heyday. Do you personally see an opportunity for Ecko to have any sort of resurgence in the market?

I'm not operating with that in mind. That's honestly on my radar. This was the right time, and place, and set of circumstances for me to do this. I'm very proud of the brand. But I'm not in any way operational. I don't own the brand anymore. But like all of my babies, Complex included, you want them to succeed. You want to build something to last. So I hope for that. I pray for that. If it's a resurgence, I would just like to see it. It'd be fun. I like designing. But I don't think I have any interest in getting back into the day to day.

The brand has been surprisingly steady over 30 years. But the market has completely changed. It's gotten to that phase where it's like, “Oh wow, we're at that.” It's kind of like the way I looked at Vans or Stüssy when I was coming up. I thought they were old, fuddy-duddy brands.

It's funny to hear you think Stüssy was “fuddy-duddy” when you were coming up. They’ve had multiple reinventions, but they’re still so popular.

The year I was getting into the business was the year Shawn [Stüssy] was leaving. It was like an industry legend thing. I remember being in the halls of Action Sports Retailer [trade show] at the San Diego Convention Center and walking by to set up my first booth. I walked by his booth area that's got like these 3D foam cutouts of signatures, that beautiful handwriting. And I remember being bitter because I was like, “He's not a graffiti artist.” Neither was I really. But that was my thinking. He was 10 years in, six years in, whatever it was. It was a pretty good head start.

My freshman class was Triple Five Soul. Supreme was starting. We were a different thing. Stüssy was like a surf brand. I remember having a chip on my shoulder, being like, “What the fuck is this surf brand trying to be all New York street?” When you're in that emerging role of trying to make your way and define your differentiation, you look at your peers and find out what you are by finding out what you're not. And I knew I was distinctly different from Stüssy. I wanted to be more like Polo or [Tommy] Hilfiger. I wanted to do much more technically complicated product. Stüssy has long evolved since then. But back then it was like seven color screen prints, board shorts, and tank tops. It was a different vibe. They did do some streetwear shit because they were big in Japan. It's just interesting how these things evolve. So who knows if Ecko will have a resurgence? It's honestly not up to me.

You mentioned brands like Tommy and Polo. At one point, Ecko had its own section of the Macy’s sales floor in the same way that those brands do. Was the decision to scale the brand in that way rooted in you trying to get to that Tommy or Polo level?

Oh, for sure. If me and you were to go start a brand tomorrow, what would we do? We would do an analysis of what we are and the brands that we admire. We would study their distribution. Today, that’s probably a lot more direct-to-consumer. But at that time, it was department stores.

You study the best practices and you ask yourself, “What does it take to get here?” People are trying to put you in a box like, “You should just be in Patricia Field or just in Dr Jays.” Not that those aren't good places. They were very good places. But I wanted that lifestyle expansion, and [Macy’s] was the path. You asked me earlier about memorable moments. I had a float in the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade in 2003. Kaws and Takashi Murakami later went on to do art balloons, but I had my rhino float years before those guys.

But part of that period was also that it wasn't enough to just be good aesthetically. You had to be good at business. And there was a period for better or worse, maybe for worse, where big was good. On a personal level, I’m proud of it. But I do think owning infrastructure is an important function as a creator. Andy Warhol said, “Good business is the best art.” The behind-the-scenes choreography of infrastructure had a lot of value. With my peers, there was a love-hate relationship with that. They loved being small. They thought that [Macy’s] was like the sellout move. But a lot of my peers, they're not getting to do a 30-year anniversary.

As someone who's been in the streetwear industry as long as you were through Ecko and Complex, how do you feel about where streetwear is currently? And what do you think is the next chapter of it?

I think streetwear is a constantly evolving space. I think it's in somewhat of a weird space. I think fashion generally is in a weird space. I have a lot of pride and enthusiasm and love for the fact that the likes of Pharrell could be the head of Louis Vuitton and that Virgil [Abloh] kept the story and the aspiration of this craft going despite the gatekeepers and the hurdles that my peers and I faced.

I'm proud of that. I’m also nervous about it. There's been this unintentional gentrification of the industry. When I was coming up, the distance between the designer and the customer was a lot closer. Even if you were like a super insider, there was still a touch to the street. Seeing all these big design houses foster that playbook is a little bit weird. At these big houses, fashion collections become almost like a cost of marketing. They don't have to perform on the basis of price point, ease of production, repeatability. They’re not operating at that level. You're selling the idea. I suppose that's the ultimate leveling of the playing field. So maybe I'm just bitter and have a little bit of envy, like, “If I had that access, what would I do with that?” But it also has a weird effect, this snake eating its tail kind of a thing, where at the highest level there's this “fashion” veneer that's all about rules. What I loved about streetwear was the counterculture, no rules. It's very hard to foster that. So I feel like it's much harder today for young operators.

Is it easier to manufacture? Perhaps. Go to Alibaba, do a Google search, you're going to find how to make some shit way easier than it was for me. You're not going to have to get on a plane as much even though you should get close to your production and know what the fuck is going on. Do you need the same sort of sales infrastructure? No. You need direct-to-consumer. So you have to really cultivate a culture between you and your audience. That's an innovation I learned more at Complex than Ecko. But it's hard. It’s an evolution. Fashion is very hard to pin down.