Hype Williams lives in his own world.

When you communicate with him—whether that be via text, phone, or in person—he speaks as if constraints don’t exist and opportunities to create greatness are infinite. One idea leads to another, which leads to another, and then another.

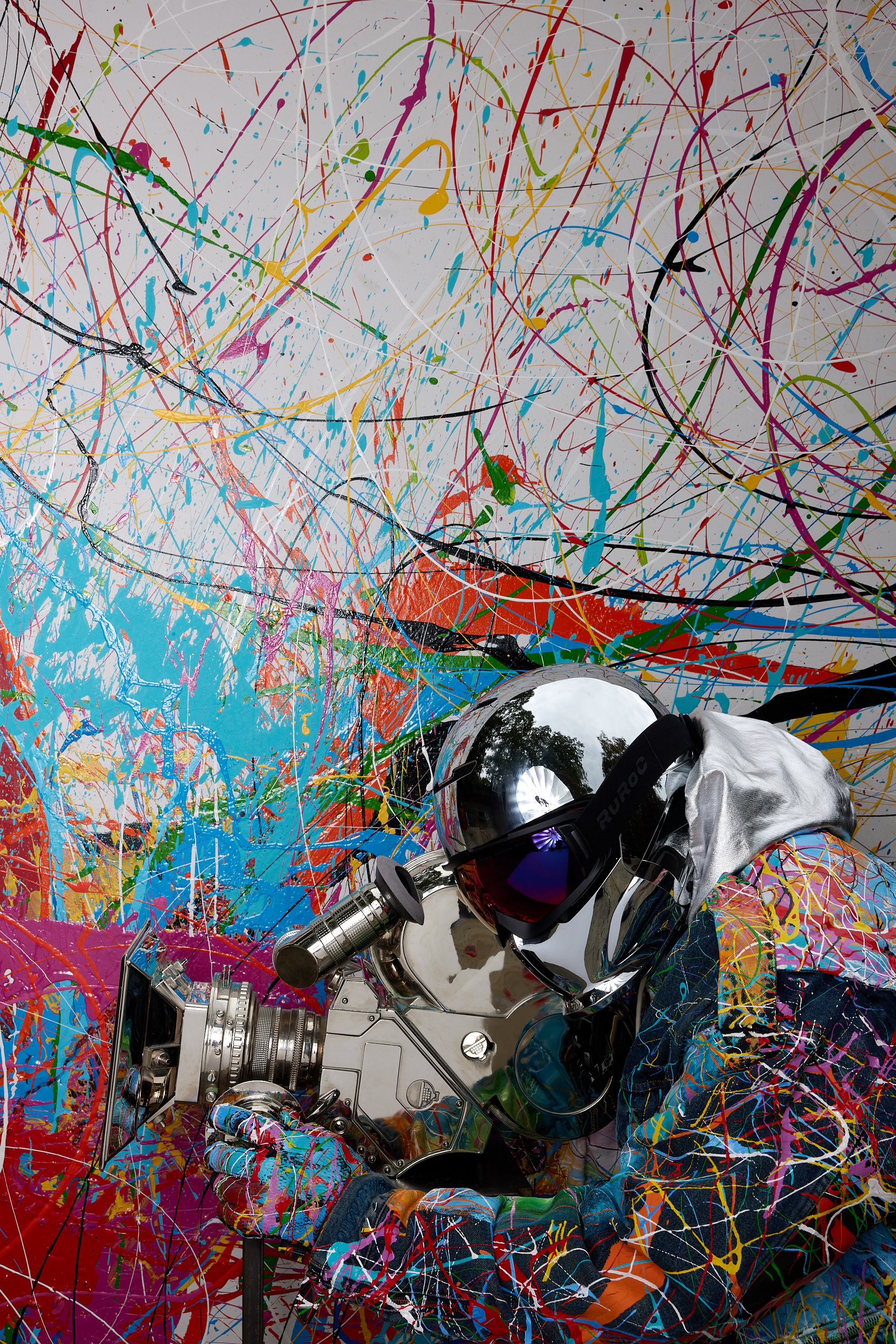

For the Ice Spice cover shoot, he was brimming with ideas. He first proposed shooting her on a yacht in the French Riviera (“I need to get her out of her environment”). Then he suggested photographing her shopping in the Graff jewelry store in Miami (his take on Breakfast at Tiffany’s). Another of his thoughts was to capture her in her element: a highly stylized, candy-colored bodega. He ended up shooting her at a slick, modern house on Miami’s exclusive Star Island on a lush bed of real flowers that were so vibrant in color that they almost looked fake. He also photographed her looking into the viewfinder of a chrome-plated Arriflex 435 camera, which he pulled from his archives—the same camera appeared in TLC’s “No Scrubs” video that he directed in 1999.

Based on his zeal, it’s easy to forget that the 53-year-old is no longer the young, hungry teenager who surveyed the music video landscape with an ambition to plant his flag in untouched territory. During the late ’80s and early ’90s, rap music videos were mostly rudimentary (shot on stoops or inside junkyards); Williams saw an opportunity to honor artists and their groundbreaking music with matching cinematic and otherworldly visuals.

Williams grew up in St. Albans, Queens, where he was enmeshed in hip-hop—he went to Catholic school with Run-DMC. He describes his parents as traditional, but because of his time spent reading comic books and hanging out with unruly friends, he approached art with a sense of fearlessness.

“I had friends who weren't afraid of stuff so they helped me understand that there's no limitations early,” says Williams. “When I was a kid, there were guns and all that stuff early. So it never dawned on me to have fears. It just rubbed off on the art part.”

Williams’ fearlessness—and impatience—is the reason why he dropped out of Adelphi University in New York, where he studied film, to join Classic Concepts, a Black production company started by Ralph McDaniels and Lionel Martin. Williams was around 19 when he started out as the gopher at Classic Concepts, then moved on to PA, and eventually became an art director, working on videos like Bell Biv DeVoe’s “Poison.”

He eventually broke out and started his own production company, Big Dog Films, in 1993, and he spent the next three decades working with the likes of Missy Elliott, Busta Rhymes, Nas, and Jay-Z on the visuals that helped cement them as superstars. In 1998, his first (and only) feature film Belly was released in theaters, which was critically panned by mainstream critics at the time but endures as a cult classic 25 years later.

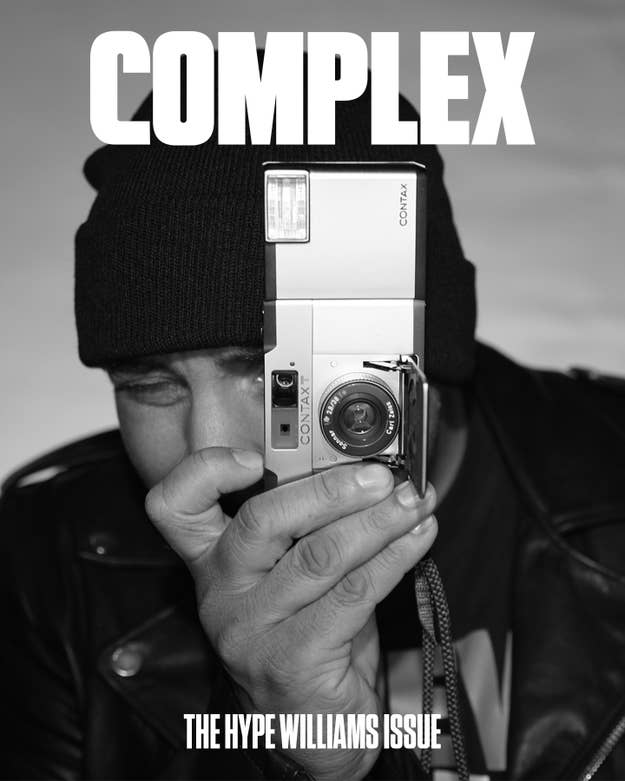

On the year that hip-hop turns 50, we spoke to one of culture’s most important image-makers about his journey, how he got the best out of talent, the challenges associated with making Belly, and what happened to that Yeezus tour film.

I want to start with your childhood. After speaking with people who worked with you, a lot of them said you are fearless with your ideas and creativity. What allowed you to be that way?

My parents were very traditional people. So they weren't the type to instill those kinds of things. It was more like I had friends who weren't afraid of stuff so they helped me understand that there's no limitations early. Like when I was a kid, there were guns and all that stuff early. So it never dawned on me to have fears. I’m shocked people told you I was fearless. It wasn't like an instance where it was like, “Oh my God, I can do anything.” It was these people in my environment who were lawless and fearless. So it just rubbed off on the art part.

OK, that makes sense. You started in graffiti, right? Isn’t that how you got your name Hype?When I grew up in New York during the ‘70s and ‘80s, graffiti and breakdancing were the two big things that dominated your youth. I didn't have a lot of talent as a breakdancer, so I immediately gravitated towards where my talent lied. And all my teachers from kindergarten on would talk about my artistic ability. So it just made sense that I would get into graffiti.

"Jack Kirby single-handedly designed my brain." -Hype Williams

I didn’t realize how much comic books were a big reference point for you. Can you talk about that?

My entire childhood I was engulfed with comic books. With comic books I was bombarded with adults who spoke to young people in an imaginative way. And my specialty was Marvel comic books. I was submersed in the idea of escapism through art in comics. There were two key people in Marvel comics: Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Stan Lee was like an editor-in-chief-slash-writer who in the beginning days came up with all the great ideas. The other 50 percent was Jack Kirby. And he’s like the [Jean-Michel] Basquiat or the [Pablo] Picasso of comics because he had a singular approach to how he drew and painted pictures. Jack Kirby used angles and expression in a way that brought him into the history of fine artists. Jack Kirby visualized the stories using colors that go past graffiti. He used colors that go past Basquiat and Rembrandt.

I think my dad got me my first comic book at 5 years old, so I’m just soaking this shit in. And Kirby single-handedly designed my brain. So it was easy for me to think visually because this guy taught me and he didn't even know. I remember when I was like 10, I forced my dad to take me to this magical place called Marvel. I didn't even know what the fuck it was. So on a Sunday my father drove me to Manhattan to the address where those guys worked, and it was just some building in New York City. I was thinking that everybody's just gonna be in there working and I’d get to meet them.

I didn’t know him, but Jack Kirby was my first art instructor, and he just happens to be the greatest artist in the history of all comic books. It's unbelievable actually. So I don't know how I stumbled onto that, but I applied it to everything. So once I got the chance to do shit, it was already there. I found out about all of our great artists like Keith Haring and [Andy] Warhol later.

But clearly you were drawn to video and went to film school, but you dropped out. Why?

Out of stupidity because everything I wanted to know I would have learned a lot quicker had I stayed in school. Film school is designed to give you an opportunity. It's designed to give you information. So I felt for some strange reason that I could get it by pushing a broom on actual stuff. But in hindsight, I wish I would have stayed because I would have gotten a lot further, a lot faster because I could have just taken the things that I needed to learn from my school experiences and then got rid of the rest. But I just wasn't a patient kid, I guess.

You got your start at Ralph McDaniels and Lionel Martin’s production company Classic Concepts. Can you talk about that?

Lionel Martin and Ralph McDaniels were the first Black music video production company in New York City. Other than what Spike Lee was doing, it was these two guys. And these two guys were the architects of ‘80s rap music video culture. They were on Video Music Box together. Lionel used to tell me all the time that he thought I was like an Alfred Hitchcock. He gave me my first book on Hitchcock. I was probably like 18. But Ralph was the one to give me an opportunity. Ralph was the producer-slash-businessman of Classic Concept, so he wanted to get more business going. So there were tons of little shitty projects that Lionel wouldn't do that he could get younger filmmakers to do. And I was like number five on the list of younger people who they thought to do stuff. I started as a gopher. I went from PA to the parking PA, to the second key PA to the Art PA, to the second to the art director to the scenic artist. I did every job that they had over there.

I want to talk about your work pre-’97. We can start with “Can It Be All So Simple.” It’s very warm and very cinematic but still street. What were you trying to achieve with your early videos?

I was just trying to get a hold of a camera to make movies. Videos gave me the opportunity that I thought film school didn't. “Can It Be” was like ’93. That was the first one I can remember where I got it right. Meaning like, here's what I wanted to accomplish and it looked like what I wanted it to look like. The prior stuff was always like, “Oh, this shit sucks. You suck. You’re no good.” “Can It Be” was the first time I didn’t suck. Somehow the photography was flawless. Like every moment that we caught was perfect. Perfect light. The biggest problem we had was those guys. They were young superstars. They were uncontrollable, and they all hated the video. When I finished it I thought it was a masterpiece. So once they said they hated it, we had these horror edit sessions. Malik [Hassan Sayeed] was one of the first guys to hustle his way to being a cinematographer. And he hustled his way into getting editing equipment. So we edited everything at Malik's actual house, which is a loft he had in Brooklyn Navy Yard. It was like a wasteland. A complete ghost town. So we would edit it at his loft. And those guys, they tortured me on that video. Like, all of the members of Wu-Tang Clan hated that video.

Did they say why they hated it?

We were kids. Who knows? It’s irrelevant. It was just whatever they thought it was supposed to be, what I did wasn't it. So we had huge fights and arguments and violent outbursts, RZA especially, because they thought I had cheated them and didn't do a good video. But with “Can It Be” it was the first time I knew for a fact they were wrong.

I was with Puff at the studio when it aired. And the whole Bad Boy crew was street guys, and they all stopped. They were like, “Yo, you don’t even know what you did.” And it also showed my name on the screen on MTV. That was like the first week or month that they started to do that. And the Wu-Tang video was the first one that people understood and saw as a visual interpretation of the music. And it changed everything. It changed everything for those guys too. They ascended to rock star status. All of us knew and loved 36 Chambers, but the “Can It Be” video was proof. Then everything after that became clear. I could just do things cinematically and it didn't matter what anyone else thought. Like, it didn't matter if people liked it or didn't like it because I knew what I was doing. So fuck everybody. Even fuck the artist. Because you motherfuckers are gonna thank me later. And guess what? They all thanked me later.

I want to talk about another one of your early videos. The “Flava in Ya Ear” remix video. People still copy that. Can you talk about what you wanted to achieve?

That was, to me, the first one that took the concept of Matthew Rolston and Albert Watson and what all these great photographers were doing and applied it to a hip-hop video in a crisp way. Puff gave me a very small budget, and he just didn't give a fuck what it was. So I had complete freedom to paint my picture. And imagine those guys are all on set in some small studio in Brooklyn right underneath the Brooklyn Bridge. The one who was the real big star other than LL was Busta. Busta was already a superstar from Leaders of the New School back then. It was like having a real-life hip-hop rock star. LL was older and he's from Queens, so we knew LL from Fresh Fest. But Busta was like a kingpin. When he came on the scene, he was bigger than Biggie. And he hated me. He was like, “Yo, who the fuck is this kid?” He really made it a point to be disrespectful because he's kingpin of Brooklyn, and Biggie and Puff and all them were on their way to being titans. And LL was already a titan. And I’m just the fucking film school kid who Puff let do the video. So me and Busta had a terrible time on that shoot until I showed him the playback. We did his shot and he acted up, and as soon as he saw what he looked like it changed everything. And then he listened. And we become the closest of friends. And we were collaborators. But it took “Flava in Ya Ear.” Busta’s moment took the video to a whole new place, and he allowed me to express myself through him after that point.

That’s so interesting that the relationship started that way. So coming into ’97 we get this big shift in visuals that seems to be initiated by Puff in a lot of ways. You were directing these very gritty but beautiful hip-hop videos, and then you have Puff who is moving hip-hop into a new space that was bright and shiny. How did you feel about that?

What's important to understand is that none of it was predetermined. The world was a whole different place. So the things that were happening for those videos were just my way of expressing myself. I wasn't a rapper. I wasn't an artist. So I just wanted to express how I felt about the music every time. All the stuff that people got conceptually or through the wardrobe or lighting or whatever was just me struggling to express myself artistically. And luckily I had a group of people who are incredibly talented and pivotal in the world that allowed me to express myself through them.

Puff was a great leader of that era. I knew Puff from the Classic Concepts days. He was already a celebrity from Howard University parties. So he knew Ralph and Lionel, and they introduced us. I was just the kid on these sets of videos that Puff was already in charge of. He was the executive at Uptown that produced and brought Jodeci to the table. He was the youngest executive outside of Michael Bivins. If there was anyone who saw greatness from my age group, it was him. Like Kanye—they are very similar types of people—he knew how to take talent and make it something. So he used me in that capacity, like an artist would use colors to make a painting. He had me in his back pocket. But I wasn't the first. He had Marcus Raboy before me. Then he had Craig Henry, who was the editor for Marcus Raboy. He directed the original “Flava in Ya Ear.” Craig was the first breakout young video guy. I was just the PA who had ideas. And Puff, who allowed me to use my ideas—we would sit in the Uptown offices and watch everything. We would watch Pharcyde videos. He would express what moved him and would ask, “Can we do anything great together like this?” Then I would go home and try to figure out how to do things great.

Tuffy Questell brought up a moment on the “Hate Me Now” video when Lou Rawls randomly showed up and Puffy didn’t want him to be in the video, but you whispered something in his ear and he obliged. Do you remember what you said?

No, but “Hate Me Now” was a Nas video. Puff didn't have control or authority over the video. So if I had to speculate, it was probably just me reminding him of that. “Yo, it’s Nas’ shit and Nas wants Lou Rawls in the video.” It’s on Sony Records and not Bad Boy. Puff was like Kanye at the moment. So he had no rules. He could have went to Wall Street that same year and said, “I’m going to start an amusement park called Puffy Land, and I need $500 million to do it.” And they would have raised the money for him to do it.

Can you talk more about your relationship with Busta and how you worked together creatively?

It’s two words: Sylvia Rhone. See, Busta was signed to Elektra Records and Sylvia was the kingpin of Elektra. So Sylvia saw whatever it was you can consider greatness in somebody like me. So she allowed things with me and Busta that she would never allow in any other capacity as a record executive because it just didn't make any sense. She showed me so much love and support and allowed for Busta and I to do whatever the fuck we wanted. No questions asked. And every time we had success, she allowed him to go further. And that's where Missy popped up because it was like Elektra was this place where Sylvia ruled with an iron gauntlet and we were all her soldiers, and I'm hugely thankful and I’m hugely lucky that I was in the right place at the right time to have someone like her give me freedom.

What people don't understand about Busta was he wasn’t improvising shit. Busta would rehearse those videos and come to set like a choreographed perfectionist. So he knew what he was gonna do with every lyric. So then when I would stop and be like, “Oh, that didn't work out,” we would do the same takes over and over again exactly the same. But he would just do it better because he had rehearsed it. He's a master, and you would just think that he was improvising. No, no, no. He would be in the mirror perfecting that stuff. He would visualize his own lyrics. So he knew how to do him better than anybody except me. Because then I knew what his process was, and all I had to do was be there at the right place at the right time per shot, per lyric, and then string all of that stuff together.

Missy was also on Elektra, right?

Yes. And no one would have allowed what we did with Missy. Sylvia and her lieutenant Merlin Bobb gave us that freedom as kids.That's huge in a corporate situation. We didn't realize the music business was corporate at the time. But Sylvia was a part of Warner Music. So she had bosses to answer to also. But she would block us from all of that and let us make magic.

And then that was really what happened with me and Busta. We had free reign to be creative, and I don't think it'll ever happen like that again. I don't think it will ever be where the artist can dictate like that. Kanye was probably the last of that where he took his power.

When you say she gave you creative freedom, what do you mean exactly?

She gave us complete control over our projects, and budgets would get fucked up. But the product was so good that it didn’t matter. I think that’s executive 101—there's a halo effect that happens with great products. All these great minds in business understand the halo effect of things. Sylvia was one of those. She knew we were changing things and we changed it. We took MTV from the rock era. And I say “we” because I didn't do it by myself. If I didn't have these artists who completely trusted me, none of that would have happened.

June Ambrose, the iconic costume designer who worked on many of your projects, called you the “artist whisperer.” And many people said you have a gift for speaking with talent. Do you think that’s true?

I don't think I'm an artist whisperer. I just think I had a track record. And once you have a track record, no matter how anybody was feeling at the time, they couldn't go against the track record. So whether it was Dr. Dre or Suge or Puff or whoever, they knew that I consistently delivered. And I wasn’t doing it for them. I was doing it for the people who are going to watch these things. They were never on my to-do list. I was never a politician or none of that dumb shit. It was more about knowing what the people were going to expect from me and this artist. So I would just dedicate myself to that. And that’s missing now. People are very quick to put themselves first and not realize that it's the people who are receiving all of this communication [that] are the ones who make or break you. This was always the way I lived my life. And it sucks because you go through hell. All these things that you were talking about are hellish memories.

Really?

Yeah. But that’s how it is. Mary [J. Blige] used to say that all the time: “If you don't walk through fire, Hype, you can't get to the other side. How the fuck are you supposed to get somewhere if you don't walk through fire?” So she lived her life like that. In those first three albums, you can hear the pain. So artistically, I wouldn’t say I was the artist whisperer. I just was gonna walk through that fire no matter what. It wasn't about nothing else. It definitely wasn't about the money, and it definitely wasn't about making people feel good. It was about going for something great every time, and then if it didn't work, I at least knew I was gonna do whatever I had to do to make it as great as it could be.

You don't think you're good with people in general?

I wouldn't say I have that skill set. But what I do have, in my opinion, is the ability to bring the best out of people. I don't think that's being good with people. I know how I knew how to challenge Puff to get him to give us more than he would give if he was working with someone he could control. So everyone is different. I learned very quickly how to get more. And I would say that's maybe the way you're trying to describe it as working well with people. But it's the opposite. It's pushing people. I know how to push Beyoncé past Beyoncé. And that's tough. Like, Beyoncé is the hardest-working human being in the history of the world. But I knew what to say to her to make her go someplace she would never go. And those little things were the things that you could see in the few things that we've done together. She's not in control.

I want to talk about Beyoncé. In a previous interview, you called her creatively submissive. And there’s that clip of her on the set of the “Video Phone” music video with Lady Gaga. She’s wearing the sew-in cornrows and she said, “I’m doing this for Hype.” So how do you influence someone who really cares about their image and push them past their comfort zone?

Well, I’ve known Beyoncé since she’s 19 years old. We never clashed. Maybe we would now since she’s a titan. But I also would never go anywhere that I knew she wasn't gonna go. I would just communicate. You have to be able to communicate. And luckily I'm a communicator. That's what this whole thing is. Art is communication. And with her, she knew we were always making a painting. She allowed my energy in there, and she didn't have to do that. She's like the Madonna for her era. She’s the biggest artist in the world. It’s not me. It’s her. Like, she decides what she’s going to have or not have, or what she wants to allow. I’m just lucky that she allowed me to be the director and submitted creatively. But that era may be gone. She may not even know how to allow that anymore. Like, for “Drunk in Love,” if you go to the BTS, she’ll tell you I never did anything like this. She completely put it in my hands. And guess what? We got a classic.

Got it. But I still want to get at how you coach talent to be their best.

So there's that layer, but it's always very simple. Puff controls everything. So you have to take his control away. The only way to do that is to challenge him and his ego. If we're shooting something and I think it’s no good, I stop him and tell him to do it again. But like, who am I to stop him and tell him what he’s doing doesn’t look right? That’s hugely disrespectful to someone like Puff. So he would immediately erupt into a violent tantrum, like, “Who the fuck do you think you are?” But none of that matters because then the next take he’s thinking, “I’m going to make sure that this fucking guy is not gonna stop what I'm doing,” and he does it better. So inadvertently you get the result. It's all that matters in these situations. Not the environment or the energy or I wanna make sure everyone feels great today. These people don't work like that. Whatever I gotta do to get them to give more is what has to happen. And this is the great truth in all things. That’s leadership, in my humble opinion. It’s about how to get better from the people you're working with. And then if they give you better, then you better deliver because you have to match their energy. I can’t say he’s not doing it right and then I don’t get the shot. I have to get it perfect. The light has to be perfect. And if it’s not perfect, we gotta start over and shoot again.

How did you work with Missy? You all have so many amazing music videos together.

Missy is a unicorn. Meaning Missy was a huge smoker, right? The weed took her places she needed to go. So she would go into this creative state through her mediums, which was the smoker shit, and she was the female equivalent of Busta in that way. I wouldn't say she rehearsed, but she was those lyrics. She’s not an artist—she is the music. So for me to recognize that it was crystal clear. I got introduced to Missy through DeVante Swing. DeVante expressed to me he had this group Sister, but really Missy was the heart of this group, and she was just hugely talented. So DeVante was like Puff. He was one of our great leaders. He helped me to understand this girl before I even met her. So once Sylvia signed her—I think she signed Sister first, and then after Sister she just focused on Missy. But we already knew who she was. So it was easy for me to work with her because I knew how great she was. What I didn't know was that she was gonna let me be the camera. She wasn’t like anybody I’d ever met before. With Busta we collaborated, but I would have to explain everything to him. With Missy, I wouldn’t have to explain shit. She was like, “Let’s go.” All I had to do was be the visual part to the music. And that was our relationship. Again, I'm lucky. No one realizes how lucky I was to be in the perfect place at the perfect time.

Yes, but you were also prepared. What was your ultimate goal with Belly?

Belly is the first script that I ever wrote about me and my friends growing up. So what I tried to express to you earlier about my environment, that’s what Belly was. It wasn't verbatim, but it's definitely where it comes from. I really got the opportunity to learn from people like this. This is who my friends were. So the film was just meant to be our Goodfellas or our Godfather. These are the movies I grew up on. I wrote Belly in like 1990 or ’91. The reason I shot music videos is because I wanted to make this movie. And then when Menace II Society came out I felt like it was all over because Menace is basically what I was going for. I was like, “Oh, man. These guys did it before I could do it.”

Malik [Hassan Sayeed] told me that you all went to Negril and visualized the whole movie. What did you want to achieve visually with Belly?

I'm lucky to have such a fantastic partner in making a movie because we both understood the culture and how important it was at the same time. So all we did was talk art and what's important to us and what the people look like or what their skin looks like in certain light, what film stocks would give us this or that. So we studied our whole little moment in the ’90s to get to Belly because all of the stuff that we watched and loved had this kind of intensity to it. The filmmakers breathed life into it by focusing on the details. So we wanted to focus on the details of Black people in that capacity in that story. It happened to be a gangster story, but it didn't matter. It was more art film than gangster movie.

Malik described the experience of making Belly as very challenging. And the reviews were bad. How did you handle the criticism?

I don't know. I'm an artist, so there's no such thing as criticism. Again, if you look at something like it's just a painting hanging on the wall, people can decide for themselves what it means or ignore it. It doesn't matter. This is what it is. But there is no art critic.

Yes, but he says you were affected by certain things that happened while making the film.

The parts that he's describing are the parts where someone has got their hand on my paintbrush. That's the disappointing part. If I know what I'm painting and I'm putting green on the fucking canvas, and if somebody says no, you should use yellow, that's the part that should never happen because I'm Picasso. You can't tell [Picasso] to use yellow when it's supposed to be green. So that’s what the great depression was about with the Belly movie. Not anything else. The fact that it could have been more if I had been able to do it the way it was intended. This movie may have been 2001. This movie may have been like A Clockwork Orange. It's still Belly. It still took it to where people still won't let it go. I'm just imagining if I got to paint a picture like a true masterpiece portrait. There's no telling what it would have been considered. It's already being considered a classic. It could have been past Kubrick. It's no regret—I just worked my whole life to do it, and I didn’t understand Hollywood. I just don't understand someone controlling Stanley Kubrick. We didn't have that information.

I wasn't making a House Party or some stupid movie. I was making something important in the way I was approaching it. We thought about every frame of that film. So for some dickhead at Live Entertainment, which turned into Artisan, to weigh in on our painting, it was an insult. So it came from a place of ignorance basically because I just didn't understand how it worked. And everyone has an agenda and a job. They don’t give a fuck if the movie was Kubrick level or not. We did. And I think what he’s expressing to you wasn’t any of that other stuff; it was just like I aspired for greatness and didn’t make it there. And then, lo and behold 25 years later, we’re still talking about the Belly movie, which for me is nothing like it was supposed to be, and for everyone else it's their pinnacle movie, their reference Bible, and all this other shit.

"Belly could have been more if I had been able to do it the way it was intended." -Hype Williams

But what did you want it to be? Because like you say, we look at it as a masterpiece. How did they control your paintbrush?

They hated X. They hated him. They tried to force me to cast an actor. And I knew that X was great and that he was the person for this movie. So as a filmmaker, I just went forward with what I knew, and I tried to express to everyone how important X was. This was before he had a record. He wasn't even an artist yet like that. And they tortured me for that decision. They tried to fire me off my own movie up until like the first day we shot the movie, based on the fact that I wouldn't let X go. And if it wasn't for Nas, Taral [Hicks], Meth[od Man], and all these people sticking by me and saying, “Well, we're not gonna show up if y'all get rid of Hype,” I wouldn’t have even got to direct the first day of shooting because they hated who they thought was a dirty convict being cast as the lead.

It's tough to be ahead of the curve. It's not a good place to be because no one else can see where the fuck you're at. This definitely relates to Kanye. He’s still ahead of the curve, and it's hard for people way back here to understand anything that this guy is trying to express and you. They don’t get it until after the fact. But this is the blessing and the curse of being an artist. Because you have to suffer for greatness. And Kanye, for every fucked-up thing that people think he's done, he broke ground in categories that artists would have never been able to embrace. I mean, every artist. So it's like the greatness of that is also the curse of it all because no one sees what the fuck you're talking about.

With Belly they were like, what is he thinking? Why wouldn’t he get an actor? And now 25 years later when you see how brilliant X is in the movie, it's like, well, no one else could have did that. When it’s that kind of thing, you gotta suffer for knowing something, no matter what it is you think you know. And every story is like that. They didn’t like Reasonable Doubt. They thought it was trash. They didn’t want to sign Kanye. It’s the way it is.

You said that Lyor Cohen forecasted that one day all of this money the industry was spending on videos would dry up. And it did. How did you adapt when the budgets started getting smaller?

The way we approached it was we fell into what we call guerilla filmmaking, which was like, OK, we'll just do the core people who need to get the stuff on camera that we want. And it makes it uncomfortable and it makes everybody feel weird, and there's no fucking support system and blah, blah, blah. But we got the best cameras in the world. We got the best lighting in the world. I got the best people in the world. So if I don't have a structure but I have the best people in the world, again, I know what I’m doing is enough to get what I need, and I didn’t have to succumb to all this stupid shit where people need 40 people around them to validate what they're doing. I had these eight. Sometimes we had six. Sometimes we had three. But it was like, no, we are gonna make magic, and if you dedicate yourself to making magic, the budget doesn't have anything to do with it.

You have a lot of work that’s never seen the light of day. What happened with the Yeezus tour doc that you worked on with Kanye that never came out?

So we decided we're gonna do a partnership. His job was to clear everything and then get it a distributor. My job was to shoot it. So we went and shot it. And it's based on the tour. We shot in two cities, Chicago and Toronto. And then a dress rehearsal where we were allowed to film the entirety of the concert, but with no people in the stadium. So I was literally able to shoot the details and close-ups of every costume and of every part of the show as if it was a video. I had free rein to do it, and we filmed all these things and it kind of got lost in what he was meant to do in terms of the agreement. I had to deliver the film, and he had to deliver some things that fell by the wayside. So by the time we got together, he already did [The Life of Pablo]. And he was like, “Yo, let’s just make this part of Life of Pablo.” So then we went and shot an additional bunch of stuff, which was the “Highlights” video. We shot a “Waves” video. We shot in Scotland. All over Iceland.

Scooter Braun and I spent six months with IMAX to release it, and when it came to the signing of it, that’s exactly when all that shit happened with Kim in Paris, and he got lost in himself and the whole thing fell to the wayside again. So no one, even Kanye, has seen Yeezus. We shot it in 2014 by the way. This is like us having like the Rolling Stones concert or some shit, or like The Beatles’ A Hard Day's Night. Like, that’s the level of movie Yeezus is, and no one has even seen it. So it may come back in a big way because that Kanye doesn’t exist anymore. So it’s historic. And by the way, it's flawless. Like, this Yeezus movie is mind-blowing like. It’s like some Pink Floyd shit. I'm lucky he allowed me to just do it. Me, him, and Drake was onstage together in Toronto for that show. It was 2014. So it'll come up in some capacity, but now it's really rock ‘n’ roll history.