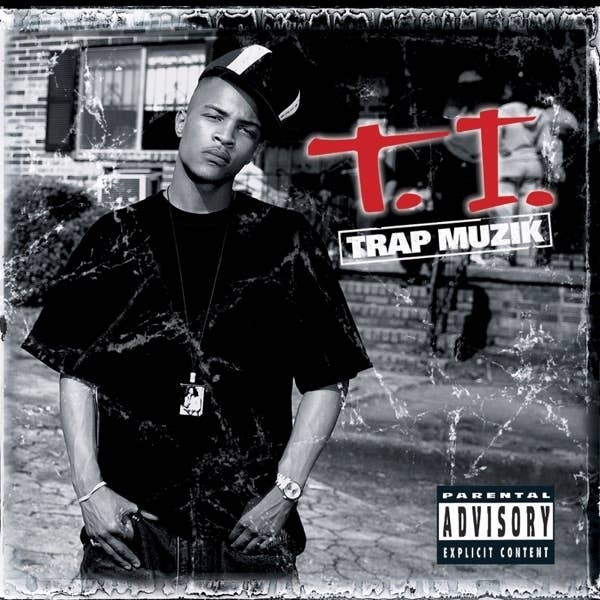

During the opening seconds of his sophomore album, Trap Muzik, T.I. offered a clarification, “This ain't no album/This ain't no game.” That’s because for him, it wasn’t. Until that time, Clifford Joseph Harris Jr. had spent most of his life serving fiends in the “trap.” He tried to change his ways and go straight by becoming a rapper, and ended up signing with Arista Records, changing his name from Tip to T.I., and dropping his first album, I'm Serious, in October 2001. But his major label debut would prove to be a major disappointment—one that failed to highlight T.I.’s charismatic appeal and his considerable skill as a wordsmith. With one foot still in the trap, Tip contemplated quitting rap for good.

In retrospect, the 2000s were the decade of Southern hip-hop. By 2003 New York had produced its last true rap superstar—50 Cent, who would absolutely destroy everything in sight that year. But by 2006 it was obvious that the power base had shifted, and Atlanta had become the epicenter of hip-hop—producing new stars for the genre and providing a new sonic template. The seeds of that Southern takeover were sowed in the ‘90s with legendary releases by artists like Goodie Mob and OutKast. The ATL takeover continued into the 2000s with artists like Lil Jon and Ludacris. But none of them really had the streets on lock. Good thing, then, that T.I. decided to keep rapping, hit the mixtape scene hard with his In Da Streets series, and released his classic sophomore album, Trap Muzik.

The album was a hit out the gate, selling over 100,000 copies its first week and debuting in the Top 5 when it was released 10 years ago today. It spawned four hit singles, “24s,” “Be Easy,” “Rubber Band Man,” and “Let’s Get Away.” The last two becoming Tip’s first of many entries into the Billboard Top 40. But Trap Muzik is better known for its slow burn, gradually growing into a platinum success by the end of the year. It wasn’t until 2004 that fans beyond Atlanta began recognizing Tip as the King of the South. By 2006's King, his bold claim became an undeniable reality.

Trap Muzik marked that auspicious moment when a King captured his throne and everybody else had to sit up and watch. In T.I.’s own words the album was “when a young man moved from the streets to come up in a major way. When he took the city on his shoulders and walked it. Welcome to the rest of your life.” So let's go back to a time when the word "trap" meant something more than ratchet EDM tracks. To celebrate the album we hooked up with Tip, his longtime manager Jason Geter, his executive producer DJ Toomp, and just about everyone else who worked on his sophmore album to bring you, The Making of T.I.’s Trap Muzik.

As Told To Insanul Ahmed (@Incilin)

Additional interviews by Edwin Ortiz (@iTunesEra)

RELATED: The Making of Kendrick Lamar's "good kid, m.A.A.d City"

RELATED: The Making of Nas' "It Was Written"

RELATED: The Making of Common's "Ressurection"

RELATED: The Making of Mobb Deep's "The Infamous"

RELATED: The Making of The Game's "The Documentary"

Before The Album

The Players:

Clifford Joseph Harris, Jr. a.k.a. T.I. a.k.a. Tip a.k.a. The Rubber Band Man a.k.a. The King of the South (Performer, executive producer, producer)

Jason Geter (CEO of Grand Hustle, T.I.'s manager, executive producer)

Aldrin Davis a.k.a. DJ Toomp (Executive producer, producer)

Sanchez Holmes (Producer)

Bernard Freeman a.k.a. Bun B (Featured performer, underground king, Trill OG)

Phalon Anton Alexander a.k.a. Jazze Pha (Featured performer, producer)

Nick "Fury" Loftin (Producer)

Lavell William Crump a.k.a. David Banner (Producer)

Tyree Cinque Simmons a.k.a. DJ Drama a.k.a. Mr. Thanksgiving (DJ)

T.I.: “Our main intention with this album was to make sure we represented the walks of life, the generation, the region, the circle, the society. After I’m Serious, we had to go our own way because we felt like we were signed to a label that did not understand our approach to music or our lifestyle.

“I was making decent money at the time, I might have gotten myself like $10K a show. But I was a hometown [hero], not a national level, I was an underground [rapper]. I guess I was more of an acquired taste. In Atlanta at that time, there wasn’t a T.I. or a Young Jeezy or a Rich Homie Quan or a 2 Chainz or a Future, none of that.

“So this is what we had to do in order to maintain creative control, as well as maintain a certain work ethic, and make sure we always put ourselves in the place to be upstanding men of integrity, no matter what. Using our experience to inform cats of our lifestyle, but not trying to glorify it so much. Glorify it just enough so people could feel like they relate to you.

“I felt like I had a responsibility to step out and show cats from the Northeast that there’s other people down here, other lifestyles, other stories besides Organized Noize and So So Def. They [looked down on Southern hip-hop] and they still do. But Atlanta had lyrics, man. We had OutKast, Goodie Mob, So So Def. They contributed, they worked wonders for the city. None of us would be able to step out here and do what we was doing if it weren’t for them.

"However, shit, man they had their chance. I felt like it was my time to carry the torch. Take this to a different level and represent the people in the streets who weren’t being represented. There are cats out here that, though they respect [those artists], they don’t relate as much to that as they do to this. I felt like we were being underserved.

“The sole purpose and intention of this album was to make sure that people coming from all walks of life would probably be motivated by being able to relate to someone. It was trying to come across so that you’d say, 'They made a change, they overcame it. So if they could do it, then you could do it.'

“I wanted to put the lifestyle out there and show kids in my neighborhood, in Compton, or in Southside of Chicago, down in Miami, or up in Brooklyn, or wherever you were staying, that if you live that lifestyle, then you could get what I’m saying, and it’s authentic to you. It was social representation. Cats living in the field were like, 'This is what I stand on, Trap Muzik.’”

DJ Toomp: “I met T.I. through his cousin Toot. Toot always used to tell me, ‘Man, I got this little cousin that you need to listen to. Only thing is that I’ve been keeping him out of trouble. He gets in trouble a lot. But he’s so talented man.’ When I heard the music, I was blown away. We hit the studio immediately. Everything just fell in place.

“What really got me with him was that his rap style wasn’t the basic A-B-C, 1-2-3 rap. He had an East Coast flow with a Southern country boy accent, that’s what made him unique. He stood out from any artist that I’ve worked with from Atlanta. I knew he was the one. I started putting my time into him.

“This is when the club scene was really strong in Bankhead, so I said, ‘I know he’s really talented, let me see how he interacts with women.’ We hit the club, Tip was pulling more females than us. He really wasn’t even old enough to get in! So I was like, ‘We got a little player on our team.’ With the music he was making and the way he interacted with the people, I was like, ‘We got a star.’

“Jason Geter wanted to get into management. Me and him were good friends before I met Tip. I was like, ‘Yo, if you want to get into management, I got your first client right here.’”

Jason Geter: “I’ve been managing Tip since day one of his career. I met with Tip in a barbershop around 1999. We were talking for probably an hour or two before I finally said, ‘OK, where’s the rapper at?’

“You gotta think, this is in Atlanta in the late ’90s. At the time, every rapper in Atlanta had the same look: Gold teeth, tattoos, dreadlocks, all kind of stuff. Everyone followed the OutKast and Goodie Mob blueprint. Whereas he didn’t have any of that, so I didn’t even think he was the rapper that I was coming to meet.

“He had a clean look, still does. No tattoos, none of that extra stuff. Just a Polo shirt, jean shorts, Air Max sneakers—that was his look. To me there was definitely an appeal. I said, 'He’s a fly young kid, but he was smart and could actually hold a conversation. But he still has the ability to rhyme and girls like him.' For me, it was a no-brainer.”

DJ Toomp: “After putting the demo together, next thing you know it got into the hands of Kawan 'KP' Prather at Arista/LaFace/Ghetto Vision, that’s how you get I’m Serious.”

Jason Geter: “I’m Serious was very interesting. He initially signed to Arista in ‘99, that was when L.A. Reid started running it. L.A. had TLC, OutKast, and Pink on Arista. All of these major artists were priorities to him, so when we put I’m Serious out, it just wasn’t on their radar.

“We started working it all ourselves. We were doing shows every week in the Southeast and Midwest regions, selling T-shirts and CDs on the road. It was like going to the label and saying, 'Hey, you guys are saying that it’s not a success, but this is what we have going. You should just support us.’

“We asked L.A. to shoot another video. He didn’t wanna shoot another video. His whole thing was, 'This album is over with, it wasn’t successful first week of sales, you guys should go back and make another album.’ We’re like, 'What are you talking about?' People love the album in the South. Go back and make another album? How do we know that the same thing won’t happen again?

“We went on strike and started doing our own thing. We ended up shooting a video for ‘Dope Boyz’ ourselves without communicating with the label. Meanwhile KP, who signed Tip, he had started working at Columbia Records. So we were on our own for real. Eventually it came to that time of, 'Can we get a release from the label? You guys aren’t supporting us, we’re not on the same page.’”

DJ Toomp: “I’m Serious was a great album, but at the same time we were still trying to figure out what the people really want. ‘Dope Boyz’ ended up being that song that was feeding everybody. We started getting more shows, shows went from $5,000 to $7,000 to $10,000, just off of that song.

“That’s when we realized, people like the street shit. So we started doing more street music. He started rapping about the trap more. When I first met him, that’s what he was talking about. But we weren’t sure if the world was ready for that. We saw how people were crazy about ‘Dope Boyz’—and LaFace wasn’t even promoting that song—that’s why we put out the In Da Streetsmixtape.”

Sanchez Holmes: “Tip’s wife Tameka “Tiny” Harris is like my sister. So I’ve been working since like back in her Xscape days. I’d stay there at the house with her. We built a studio in the basement of her house and I was always there working. [This is when Tip and Tiny first started dating so] he would come over to the house. He came downstairs one day and was like, ‘What you doing down here?’ I start playing shit and he started rapping on them. He rapped on like four or five joints that same night. That stuff ended up on In Da Streets.”

Jason Geter: “We were selling physical [copies of In Da Streets] to mom and pop stores when you could still made money on mixtapes. Every week we’d be doing deliveries and shipping them off. It was very successful for independent retailers during that time.

“We used to be running up on bootleggers, taking our CDs back—that’s how people knew us in Atlanta. We would run up on bootleggers and bootleggers started pulling guns out. We’re like, ‘Oh shit, now it’s getting kind of far.’ But they started knowing like, 'Them dudes gone come up on you and grab their shit.’ At first, it was like, 'Hey, you’re taking money from us'. Then when your success starts to grow you say, 'I can’t fight this anymore. This is a full-time job trying to fight.'

“We started getting our funds together doing all of the work on our own. Now you gotta remember this is when Master P and all those dudes was on fire. So it was like, 'Let’s start our own company called Grand Hustle, do our own album, do our own label, and put out our own music.'”

"Trap Muzik" f/ Mac Boney

Producer: T.I., San "Chez" Holmes, DJ Toomp

Jason Geter: “We actually started renting out a room in the back of Mac Boney’s mom’s hair salon. We had a Roland 2480 machine. Truth be told, Trap Muzik was 90% made in that back room of KBJ’s Beauty Salon on this Roland 2480. We would come when it was closed and leave before it opened up. Sometimes we’d be creeping out of the back door with old ladies coming in the front door to get their hair done.

“It was interesting because the neighborhood that we were in, like Bone Crusher was around the corner working. He had a studio and David Banner would always be there. Lil Jon used to work not too far away. Everyone from Atlanta that rose during that time had been working around each other, hitting the same Chitlin Circuit tours, going to the same towns. It wasn’t a ton of people around at the time.”

T.I.: “My big cousin Toot introduced me to Toomp because they grew up together on the Southwest side. My cousin, he was deep into the other side of the lifestyle, not so much music, but very deep into the other side of it. Not in the common, expected way either. He had a way of putting himself into positions that would keep him financially stable.

“He pulled up on me and he said, 'Hey, man, what you doing out here all alone and shit?' I was like, ‘This what I’m doing, help me.’ I was talking about him helping me on another note, you know what I’m saying? On the things that I knew that he knew how to do. He was like, 'Man, can’t you rap?' I was like, 'Nah, the shit ain’t working.' He was like, 'Man, I can help you with the raps, but I can’t help you with the other shit.'

“So basically, he took me over to Toomp. Toomp gave me a—it wasn’t even a CD—it was a damn cassette tape with some beats on it. I called him later on that night and said, 'I’m ready to go.' We get in there, did about three of four records.”

DJ Toomp: “We named the album Trap Muzik. We built the album off that concept. That’s why we had the skits in there, he went into details about the trap at the beginning of the song. Took you through the journey through the trap basically.

“Tip actually created that track and then I came in and finished it up. Tip produced too, if you give him a drum machine and a keyboard, he can get it down. That’s what also makes him an overall good artist. He gets it. He understands the artist side and the production side of the game. The same aspects that made Kanye what he is.

“I was there for really the whole album. Even the stuff that I didn’t produce, I was there just to make sure everything went well as far as the delivery, the lyrics, the direction. There were a lot of songs we recorded where we were like, ‘Ehhh, that song doesn’t need to go on the album.”

Sanchez Holmes: “It was crazy because it’s three different songs in one but we loved every part of it. All three songs were dope so we said why don’t we make them all one because they was talking about the same thing. It was T.I.’s idea. Creatively the boy, the dude is a genius, man.”

T.I.: “The intro track, that was probably one of the easiest records to make. It was an exercise in expanding and taking matters in my own hands [by producing part of it]. Since I wrote it, since I know what it sounds like in my head, let me put the beat together. The song came to life.”

"I Can't Quit"

Producer: Benny Tilman & Carlos Thornton

Jason Geter: “Tip is the kind of artist that expresses what he’s going through with his music for real. The title alone shows you what the guy was going through. You got to hear his frustration, his determination. Back then the whole thing was, 'Oh, he got dropped from the label.’ But we asked for a release, we asked to get off the label. People were doubting.”

T.I.: “I thought about seriously quitting rap three times for sure. After I’m Seriousdidn’t get the reception that I had hoped, I felt like maybe it ain’t meant to be. Maybe I ain’t gonna cut it. Maybe it’s not worth the trouble that it’s starting. Maybe this ain’t a game that I can commit myself to and still live a healthy lifestyle. Maybe I do need to bow out.

“I felt like if I would still be going to jail and shit, I might as well back in the game. When you’re let down by your ambitions not being met with reality, it takes the best of us to pick ourselves up and say, 'Fuck this feeling sorry for yourself shit, man. You gonna finish it, or you gonna say fuck it.' I said I was gonna finish it. So many people depended on me, That was exactly why I felt like I can’t quit.

“I was just like all the other motherfuckers out there, trying. I felt like ain’t nothing keeping me from being what I wanted to be, keeping me from the opportunity. I think the history has shown, that’s exactly what it was. All I needed was a plug, a connect. Once I had a connect, I’ve been going ever since.”

"Be Easy"

Producer: DJ Toomp

T.I.: “'Be Easy' was a term that me and my partner just started saying back in the day. A lot of the shit on that record was just things that me and my partner would say. It just made its way into my music.

“I wanted to make people feel about me and that record the same way that people felt about Black Sheep when they came out. The laid-back, cool... Cause I ain’t one of those other cats out here. That was my sole purpose with that particular record, to separate myself from the rest. Like, this ain’t that.”

DJ Toomp:“I took a little piano sample from Al Wilson’s ‘Somebody To Love,’ and chopped it up and put beats behind it. 'Be Easy' was the beginning of a lot of things. Shawty Redd, that’s his favorite song. When you listen to a lot of Jeezy’s stuff on his first mixtape, a lot of what Shawty Redd was doing, he got the pattern from the 'Be Easy' drum pattern. It’s good to know that it had such an influence on a project like that.”

Jason Geter: “'Be Easy' was the record company’s pick at the time. They were like, 'Hey, let’s go with ‘Be Easy’ after ‘24s.’’ We were getting the new relationship with a major label. But 'Rubberband Man' came after 'Be Easy,' which totally started taking a life of its own and then we got forced into doing 'Rubberband Man' immediately. 'Be Easy' wasn’t even around that long, honestly.

“The reason why we decided to go with Atlantic Records was because they didn’t have anybody that was dominating. We looked and we saw they had Nappy Roots. I said, 'Man you guys gave Nappy Roots four videos?' I said, 'If we go over there, you could really run this building.’

“But they’re not like Def Jam. They never had that practice of throwing a lot of money out there. It’s really like a conservative approach. That’s why the album had that slow burn is because it was organic, grassroots. It wasn’t this huge marketing campaign, which is what we saw from some of our peers.

“We saw Bone Crusher have the hit record at radio and the huge campaign. But that just wasn’t Atlantic’s style of doing business. It was more, 'Instead of dumping a whole load of money on one record, we’re gonna stretch this money out and we’re gonna do four records.’ That’s why the album was real gradual.”

"No More Talk"

Producer: Sanchez Holmes

T.I.: "'No More Talk' was one of my more political records. I wanted to take the opportunity to get in the booth and share my political views. That’s probably my version of a Nas-type record—one of those 'Hate Me Now' type records. A little Public Enemy, a little 2Pac.

“I felt people responded to that because it was an opportunity to peek inside a lifestyle you wouldn’t be privy to if it wasn’t from that particular source.

"There’s cats from that same walk of life as mine that wouldn’t even talk the shit that I was talking about on that record. You wouldn’t be up on this shit that I’m talking about on a lot of these records had it not been for me telling them about it. They wouldn’t know it. And I ain’t talking about no rappers.”

Sanchez Holmes: "He had something on his chest he wanted to get off, he was done with talking about it and wanted to let it be known. Like, 'I ain’t speaking about it no more, it’s done. They can take it how they want to.' He was that hotheaded street dude, you couldn’t tell him nothing, man. He didn’t just say that [on the song], he meant that and you know it was all for real. Shit like that was happening on the daily. Like every record came out, that same day something was being dealt with."

"Doin' My Job"

Producer: Kanye West

T.I.: “That’s my favorite record I’ve ever made. Those kinda records have a special place in an artist’s heart because they’re pulled from our lives. Rapping about some of that shit on records, that’s a way of us re-living those circumstances. There is no way I can say some of that without thinking about what happened and my relationship with my thoughts— good, bad, or indifferent.

“It’s real-life shit that went in that song. We was 14, 15 years old, and we used to cut school, hustle in front of the apartment, all day, all night. We kept a low profile. But there were a lot of old ladies, moms, and people who were there. They would see us dealing, breaking the law. While we was back there, there were break-ins, there were stolen cars, we out there doing what we doing, but [we weren’t doing that]. We wanted shit to run smooth too because we need this to operate.

“That song was me being able to clear up a lot of the ways I felt. Even though I was removed from that environment by then, I got an opportunity to speak on it. On a song, there is no interruption. It’s gonna force you to listen and think. That’s one of the most special records because I knew there was so many people who were willing to say the same shit, they just didn’t know how to articulate it. It gave me great pride to be able to convey that message. That opportunity doesn’t come often in music, especially the kind of music that I do.

“'Doin’ My Job,' that was my very first time working with Kanye. He came down to Atlanta to the studio. I remember hearing 'Jesus Walks' and I was like 'Oooooooh, I don’t know—that shit sound risky.’ That shit popped though. When I was telling Kanye, 'I don’t know, bruh' my homeboy was like, ‘That shit go.’ Kanye and my homeboy were absolutely right.”

DJ Toomp: “We figured like, ‘OK, we’ve got the Toomp feel. We’ve got the down South stuff, let’s get some different producers.’ We decided to reach over to Kanye. It blended perfectly. Kanye definitely brought balance to the project.

“We kicked it hard [with Kanye]. We went to the strip clubs with him. They had female wrestling and everything. We introduced Kanye to Atlanta for real. It was great to show somebody around Atlanta at that time. There was so much to do.

“That’s when Kanye was still trying to develop as an artist. He had already established himself as a producer, but he was playing demos like, ‘What do y’all think about this?’ It was the beginning of his career as an artist, and that’s the interesting part about him being infatuated with us for about a good week or so.”

"Let's Get Away" f/ Jazze Pha

Producer: Jazze Pha

T.I.: “[A song for the ladies] was just a natural progression. That’s just who I am as a person. It’s a part of my duality. It allows me to have a diversified fan base, whether it’s mothers and daughters or sons and fathers. I’ve been fortunate enough to be on the positive end of that transition.

“The video was awesome. We went to Miami and we really just turned up. The only bad thing about it was that I shot that video and then I had to go turn myself in for a probation violation right after. It was a pretty good going-away party.”

Jazze Pha: “I met T.I. through DJ Toomp and Kawan Prather. T.I. only had a couple songs recorded at that time, but he had a record that I loved called ‘Lap Dance.’ T.I. had a lot of style about him. It wasn’t about expensive clothes because he didn’t have any expensive clothes. It was just his style. He had an arrogance, but it was cool. I was in Miami and T.I. called me from Los Angeles and was like, ‘We need to come up with a record that’s vibing for the girls.’ I just came up with it.

“[I tried to sample] Aretha Franklin’s ‘Day Dreaming.’ I had originally done the record singing that same melody. They were like, ‘We couldn’t use it because we couldn’t get it cleared in time.’ So I changed the melody and I made my own melody out of it, and people really gravitated toward the melody I changed it to. Then when the video came out, they changed it back. That was an executive decision which I thought we didn’t really need. I didn’t think we needed the sampled version because our fans didn’t really know that record anyway, so it’s not like there’s no real nostalgia for them with the record.

“I don’t think [‘Let’s Get Away’] was contrived with T.I., it just happened naturally. I don’t think it was like, ‘I’m going to make pop records’ or ‘This would be a great pop record.’ He just tried the ideas that were presented to him. A lot of times he had his own ideas because he was a producer too.”

"24's"

Producer: DJ Toomp

T.I.: “After I’m Serious my people were telling me I had to dumb it down. After my songs got a lot of local acclaim but no commercial success, everybody felt like most of the records were too wordy for the sound of the time. You have to have a balance between songwriting and lyricism. There has to be a duality in order for it to work properly. So, I told them, ‘Aight, cool. Money, hoes, cars, clothes/That’s how all my niggas roll.’ After that, I just gave it a little melody, shot a video, and put a bunch of rims on the car and the truck. When I perform, that’s still one of the records that everybody goes nuts to.”

DJ Toomp: “Once he started saying the hook, I started playing the track over and over again. I knew what it was. Before you know it, we had a hit record. That song is what really got us the deal at Atlantic.

“That album was like somebody advertising a new product. Like somebody stamping my work. I had my sound, but it just took that right artist to get on it and for the right records to be written to it. I come from the Miami Bass movement, all the booty shake music, but I still included the 808 drums and a slower style of music. I was trying to get on OutKast and Goodie Mob but they already had their signature sound with Organized Noize. The stuff that I was bringing didn’t fit with where they were going.

“I knew I had to find that right model, that right person. I knew once Tip got on there, people were going to acknowledge what I was doing as a producer. Then, boom, I started getting more work from there. My catalog built and I started making relationships with different publishers.”

Jason Geter: “I remember going to Savannah, GA and doing a show. The radio program director came to the show and said, 'This is a good-sized club that this promoter booked and there are people outside that can’t even fit into this club right now.’ He said, 'Whatever record you guys have, send it to me, I’m playing it.'

“We had just made '24s' so I sent that record to this guy as well as a ton of other program directors. It started getting spins in our markets. The record started being successful at radio and then the bidding war started. Which led to us doing our deal with Atlantic.

“When we did the deal with Atlantic, '24s' was already in the market. We signed the paperwork, the following week we shot the video for '24s.' For Atlantic, it was like you guys need to catch up to the demand. We didn’t have no A&R process. It was none of that from Atlantic.”

"Rubber Band Man"

Producer: David Banner

T.I.: “Back before I was fortunate enough to do what I loved for a living, I used to make my money when the sun went down. Back in those days, the rubber bands that you had on your wrists were in hope of the funds that you would incur that evening. If someone is walking around with four or five rubber bands, they probably have about $4,000-$5,000 worth of work to sell. So by the end of the night, these rubber bands are going to be on these bank roles and not on our wrists. That was our lifestyle.”

“After I garnered some success from '24’s,' 'Rubber Band Man' was the follow up. Basically, I was naming people who had been fucking with me first, since like I’m Serious. I just wanted to show my respect and say thank you to places like Cackalacky, which is a slang term for Carolina. The idea was, they support me; I support them. Even exchange, no robbery.

“We toured the Southeast and Midwest regions so we appreciated all of the towns and neighborhoods that embraced us like Duval, Columbus, Gainesville, Tallahassee, Memphis, Chattanooga, the Carolinas, Mississippi, St. Louis, Detroit—all those places. We were doing a show in those places like three or four times each year.

DJ Toomp: “Tip wanted to do a rubber band song a while back, but he wanted to do something with The Spinners’ 'Rubberband Man.' We kept listening to the record but there wasn’t a way to make that record bounce the way we wanted it to. Once he heard that David Banner beat, he kept that concept; he just didn’t use The Spinners’ melody. The title 'Rubber Band Man' was always embedded in Tip’s head, he always wanted to do a song based around that. That idea was in his head for about a year and a half before he finally heard the right track to bring it out of him.”

David Banner: “Originally, I was in a group called Crooked Lettaz. I was signed to Penalty. Penalty folded and I ended up going to Tommy Boy. Bone Crusher was in a group called Lyrical Giants. When all the Tommy Boy stuff dissolved, me and Bone Crusher became really good friends and we were both really really really broke. So, we came up with this team.

“I was like, 'Bruh, if I’m producing for somebody and we need hooks, I’m going to come to you for the hooks. If anybody need a beat and you doing hooks, you come to me for the beat.' Bone Crusher ended introducing me to everybody in Atlanta that was hot. From Toomp to Lil Jon to T.I., everybody. I played some beats for T.I., T.I. really liked them.

“T.I. told me, he said, 'Listen Banner, I have to basically take care of everybody that’s around me. If you work with me on the price for these beats, I’ll make it worth your while. I promise you that.' I drove from Mississippi to Atlanta to work with him.

“Just about everybody in Atlanta that was hot during that time heard that beat and T.I. was the only one [who picked it]. Everybody liked my beats. I remember Mr. DJ, who was the DJ for OutKast, said to me, 'Banner you two years ahead of everybody, you just have to be patient.' T.I. was one of the people who had the vision to see it before those two years were up.

“I had been doing the ‘David, David, David, David Banner' drop a long time before 'Rubber Band Man' but radio stations used to chop my tag off. T.I. was the first artist to tell radio stations not to take my tag off of his song. That really opened it up for other producers to put their tag at the beginning of the songs.

“'Rubber Band Man' was similar to when Busta Rhymes came out with 'Woo Hah!! Got You All in Check’ for New York. It brightened the scene up. Music was so dark, especially urban music from the South. It had gotten so aggressive, so mean. Although he’s talking about, you know, 'wild as the Taliban,' the beat was na-na-na-na, like it was happy. That one song changed the tone of music. You heard them 'Rubber Band Man' chords in about 12 songs after that record came out. It sort of changed music into that bright music with hard subjects.

“That song was what allowed me to charge people what I get now for beats. People won’t admit it, but there’s this Mason-Dixon mentality that people have. I can have the same résumé as a producer from another part of the country and labels don’t want to pay you the same thing because you’re from the South, unless you’re connected to a Jay Z or somebody like that. After 'Rubber Band Man' I didn’t have that problem no more. That made me officially that platinum producer. That beat ushered in a new style of music and it also ushered me in as a producer. That record meant a whole lot, not just for me, but for several people.”

DJ Drama: “It was pandemonium [when ‘Rubberband Man’ came on in the club]. That was a huge record.”

Jason Geter: “‘Rubberband Man' was the turning point. That showed the world what was going on in the South. You had artists like Puffy that would come to the market and be like, 'Who the fuck is this kid?' Puff befriended us and wanted to sign Tip to Bad Boy. He came to parties and showed us a lot of support. For 'Rubber Band Man,' Puffy cosigned us [by being] in the video. That cosign definitely [had people asking], ‘Who’s this kid that’s not on Bad Boy that Puff is in this video with?’ That was maybe one of Puff’s first times doing that for a Southern artist.”

"Look What I Got"

Producer: DJ Toomp

T.I.: “I remember, I think it was The Source or XXLor one of those magazines, they rated my first album not like I hoped. I'm saying to myself, ‘These people don’t know what they are listening to and they don’t know what they are listening for. Let me set the record straight. Let me separate myself from the rest of these cats. You can’t tell me what’s right about this.’

“That was one of those records that demanded the attention of people immediately. That’s one of my favorites, definitely one of the most memorable from the album. The subject matter, the tempo, the beat, lyrics; it’s ghetto hood. It made people say, ‘Wait a minute. This man thinks he's got it, but you could tell it was authentic because everything he is saying sounds true. I believe it. I don’t know this guy, but the way he is talking I feel like I should know him. Why don’t I know who this guy is?’”

DJ Toomp: “That’s a lot of people’s favorite record. 'Look What I Got' is one of the records that’s a celebration. He was really speaking for all of us on that record. New deal, new cars, new cribs, just being able to do more. He just felt good.”

"I Still Luv You"

Producer: Nick "Fury" Loftin

T.I.: “It was emotional making that song because my father had just died or was about to die. He had Alzheimer’s, diabetes, and high blood pressure, so he was really hurting. Even though he had Alzheimer’s, he knew me when I came around. I remember he kept telling me the same things he would tell me when I was a kid, like I was still a kid. But sometimes he recognized I was grown, like when I brought my around my two sons, Messiah and Domani.

“The first verse was to the first young lady who I had two sons with. It wasn’t my fault. I grew up, the same things I wanted then aren’t the same things I want now. It doesn’t make me a bad person, it just makes me a different person than I was when I was 16 years old. I didn’t have this mind to think with or this experience to go off of. You can’t hold my feet to the fire for that. Even if you do, don’t worry about it I still love you.

“[The second verse is about how] I had resented my father for a long time before he got sick because I felt like he was able to prevent me from having to go through what I went through as a kid. I felt like he was very well off. He lived in a nice Manhattan apartment and I would go to see him every summer. He didn’t worry about no bills, he didn’t worry about no food, he didn’t worry about none of that. But, when I went back home and I was supposed to focus on school, I had worry about like, ‘How am I going to get bills paid for my mother?’ When I got older I resented that.

“When he got sick, I started making it on my own and had kids on my own. It worked out a little better for me than him, I’ve been more fortunate. But I understood the struggle. I knew it wasn’t just him saying, ‘Fuck me,’ and leaving me out there. I understood the challenges at that point. Even more than that, that’s my father and he gave me life so the resentment, it was time to let that shit go. We spent his last days together. I made that song to let him know that all is forgiven. I’m not tripping.

“I was in a relationship with a childhood sweetheart before I got my record deal. Once I got the deal, she had my first son. She’s was pregnant with my second son, but we weren’t working so we broke up. Meanwhile, I met a friend, we started kicking it, and she got pregnant with my daughter, Deyjah. I wasn’t ready to accept that I got three kids in two years so I ran away from the responsibility with the friend of mine. I didn’t embrace my daughter in the first three to six months of her life as I should have, and [the third verse in the] song was my apology to her. Saying, ‘This is what it was and this is what happened. It’s not your fault; it’s my fault. I just didn’t know how to handle it but now I get it.’”

Nick "Fury" Loftin: “I met T.I. in the late ’90s. I came up with T.I. and Cee Lo Green. We were all on the grind. Nobody was famous, nobody had money like that, nobody was established. I was working with Kandi Burruss from Xscape up in Tree Sound Studios and she told me, ‘There’s this artist in the next room with my guy Kawan Prather.’ I was like, ‘Oh yeah, I heard of Kawan.’ She’s like, ‘I want you to meet his artist.’

“So Kawan came over, met him, then we went over to Tip’s room. I walked in and I was like, ‘Wait—hold up man, I know you!’ I played him beats, he picked a few of them. I left a CD and didn’t think anything about it.

“It wasn’t until a year later when I came back to Atlanta and I saw Jason Geter and Mac Boney. They’re like, ‘Man, we got this track that we’re going to put on Tip’s album, but we don’t know who did it.’ So I went to the studio, they played it, and it was ‘I Still Luv You.’ It just so happened to be mine. It almost didn’t happen.

“T.I. had already recorded a demo version of the song, so he had some ideas of what he wanted to do. I was tracking the beat, he heard it, and it was an emotional song for him. He wasn’t really saying too much, he was just listening to the track. Then he was like, ‘OK, I’m ready.’ I had never seen an artist really just go in there and go from the top of the head. He went in there and laid those emotional lyrics down, and at the end of the song he’s like, ‘I’m done with it.’”

Jason Geter: “People who rap, you can tell they rap. Sometimes they always walk around saying little lines. He does none of that. He’s a rapper but he never raps until it’s time for him to go in the booth. He’s a real strong dude. He’ll go through stuff and he’ll hold it; he’ll try to wear it as a man. He won’t cry about it, but when he gets in the booth, it all comes out.”

Nick "Fury" Loftin: “The crazy part is I was going through some things with my daughter’s mother and just life issues, and I brought those feelings out on that track. So to have him come on that track [and feel the same way] I felt when I made the track was just amazing. It was like the perfect marriage. I could listen to that song today and hear my story in that song.

“Not too long ago, Tip told me some of the early records that I did for him helped him form his career. I was like, ‘Wow, that’s amazing.’ Before I tell people I did Lil’ Flip’s ‘Game Over,’ I tell them I did ‘I Still Luv You.’ They say, ‘Oh man, I used to listen to that going to school! I used to listen to that at night.’ I didn’t know it made that much of an impact, but I guess it did.”

"Let Me Tell You Something"

Producer: Kanye West

T.I.: “That record was for Tameka ‘Tiny’ Cottle. That’s a love song about me becoming infatuated with a young lady that I just encountered. That was the first time being around one another, so that record was a description of how I felt about our relationship at the time. All my shit is based on my life. I guess the song contributes to the meaning and the album’s relation to my life. How the things that I was going through then are still the things that I'm going through now."

"T.I. vs. T.I.P."

Producer: T.I.

T.I.: “L.A. Reid asked me to change my name to T.I. when I was on Arista. Some of my partners were like, ‘We told you you should have never changed your damn name.’ When I got off Arista, there was a thought that I should change my name back to T.I.P. Everyone was like, ‘Nah, people have already started calling you T.I.’

“So that was a conflict on whether or not to change my name back to what it was originally. Would that garner the success that I had been missing on the first one? Was T.I. something that I was trying to turn myself into that really wasn’t me? All of those questions arose in the making of this album. The thought of 'T.I. vs. T.I.P' was really just me dealing with the battle within myself.

“I characterized both of them. Both of them are me. It’s just one part of me that people feel would be more conducive to success and one part of me people feel would be more conducive to danger and destruction. I was taking the smart parts of me and the dangerous parts of me, individualizing them—with two names that people both know are related to me—and having a conversation between these two people.

“Everybody talks to themselves. Everyone says, ‘Why did you do that? What were you thinking?’ I just did it on the mic, went in-depth, and spoke about the things that I knew I should be speaking to myself about in front of everybody.

“I’m not just a one-dimensional, hot-headed, temperamental, irrational, violent, extremely hip-hop artist. I always wanted people to know, I’m capable of this but I can do that too. People always try to put me in a box and make me be a gangster, a drug dealer, a backpack rapper. Just let me be me. This is who I am right now, a pretty boy, a thug, a hoodlum, Casanova, ladies man. Let me be the things that certain times call for. I don’t want to be so locked into one thing that I can’t change.

“People are very critical of humans. ‘How can you be a family man, non-threatening? This guy must be fake.’ What you’re telling me is that I’m supposed to be banging at breakfast? I’m supposed to wake up, roll over out of my bed, with my children in the house and pull a brick out my bag and whip up some dope on my kitchen counter? That’s what you’re telling me? Man, get the fuck out of here.

“That dichotomy and duality, that contributes to the diversified commercial success I've had and the foundation of respect that I hope my career will have. I think I’ve gotten pretty close to it at times. Sometimes I’ve walked a little too far on one side or the other—but I think I’ve done aight. Given where I started from and what I had to work with.”

"Bezzle" f/ 8Ball & MJG & Bun B

Producer: DJ Toomp

T.I.: “That one, we were just really kicking slab with the cats that I respected in the game and felt were most important. We didn’t want to try and go get a big feature. I'm not saying they weren’t big because they were huge in my eyes, but I'm saying we weren’t going to run around saying, ‘OK get him, get him, get him, get him,’ I wasn’t with that. I went through that the last album.

“I was like, ‘Listen, I don’t need anything. The motherfuckers around me respect me enough.’ So 8Ball, MJG, Bun B, were major figures in the culture. They cultivated my career and they were some of the first Southern lyricists along with OutKast, Scarface, and Goodie Mob.

“Usually motherfuckers from the South were known for booty shaking and crunk music, but they were some of the first actual lyricists. I knew the booty-shaking shit wasn’t for me. I listen to it, watch girls dance to it, but I can’t do that. I would listen to a lot of New York music; Eric B. and Rakim, LL Cool J, Das EFX, Leaders of the New School, A Tribe Called Quest, Brand Nubian.”

Jason Geter: “Tip is from Atlanta, but a lot of people don’t know his father lived in New York. Growing up, Tip would go to New York for the summer time. Tip will tell you about Harlem like, 'Growing up, I would always go here and there.’ You’d be surprised, like this dude really knew Harlem. That’s how I think a lot [New York rap] influenced him.”

Bun B: “I’d known about T.I. for a while in the Atlanta rap circles. I’d watch him come up and grind, especially through all the mixtapes he had been doing. I was really impressed by his lyrical game. I was definitely down to support him doing that album.

“He said, ‘I want to make sure that I get a really raw song for you to get on.’ I said, ‘Cool. Let’s do it.’ That was the track he came back with, he told me, ‘It will be me, you, 8Ball & MJG on the song’ I said, ‘That’s a great lineup, it makes a great statement for you as an artist linking up with guys like us.’ When I heard the track and I heard how he was coming on it I thought, ‘Okay, I'm going to have to really deliver on this track.’

“T.I. has always been a really mature person. He’s always known exactly what he wanted to do. So my only advice was to keep doing what you’re doing. There was a direction that they were trying to send him in with his first album, and he realized that it wasn’t the way he needed to be going, so he put forth the effort to try to bring together something that was more representative of him. I told him, ‘When this music comes out it’s going to represent you. You should definitely make the music that you feel is a true reflection of you.’”

DJ Toomp: “Boy I wish we had made a video out of that one. We were basically done with the album and I was in the studio just playing around. The sample that’s in that record is from one of Tip’s records called 'I’m So Tired.' I produced 'I’m So Tired' for I’m Serious but it didn’t make it, so nobody had ever heard it. There's a part on that record where he says, 'You saw the drop top like the bezel in my watch.' I took that line, chopped and screwed it, put another beat around it.

“When I put that track together, I called him. I was like, ‘Hey man, I know we might be done but I got one more track that y’all need to hear before this album is done.’ When I came down there and played it, everyone was all thumbs up, like, ‘Yup, that’s a go.'”

"Kingofdasouth"

Producer: Sanchez Holmes

T.I.: “I was riding with my partner, Kawan ‘KP’ Prather, fresh out the trap. We were working on the Shaft soundtrack because he was the A&R for that. We were listening to one of Mystikal’s albums, and he called himself the Prince of the South. So I said that, ‘If he’s the prince, who’s ever been the King of the South?’ KP said there had never been one.

“KP always said he could see when I had a thought, like I show something on my face. So as soon as he said, ‘There has never been one,’ I looked a certain way. KP said, ‘I bet you won’t do it.’ I said, ‘Who won’t do it? Take me to the studio.’ That night, we recorded '2 Glock 9’s' with me and Beanie Sigel and I did it right then.

“I didn’t have a huge campaign or marketing intentions behind it. It was really just some shit my partner said I can’t do. If a motherfucker tells me I can’t do something, watch me do it. They told me I couldn’t run a 5K race without any preparation because I had been smoking weed and drinking liquor. The night before I did a show in Detroit, that morning I went and did a verse for Kid Rock in his studio, got on a jet, landed in Atlanta at 9. Slept in the car, went straight to the race in some Jordans and some basketball shorts. I ran 3.3 miles in 18 minutes and 45 seconds. No bullshit. True real talk. This shit is documented. I ain’t just talking shit. I was sore as fuck for about four or five days.

“That’s how the King of the South started. It didn’t have as much value to me as it did when people started saying I couldn’t say it. People started saying, ‘Who does he think he is? He can’t say that! OutKast are the Kings of the South. Scarface is the King of the South.’ Aye, listen man, who the fuck are you to tell me what I can’t say? If you don’t like what I’m saying, come stop me from saying it.

“What I did, because of the amount of respect I had for these people and the role they played in my upbringing as an artist and a lyricist, I spoke to all four members of Goodie Mob, I spoke to OutKast, I spoke to Bun, I spoke to MJG. I spoke to all of the people that I respected and everyone told me, ‘Do your thing. You cold as a motherfucker. You one of the coldest niggas coming out right now.’

“So I always felt like, if the legends aren’t saying shit to me, then fuck what you have to say. Not one of y’all niggas are on my level. Y’all can’t see me in the street, y’all can’t see me in the booth, so what the fuck can you tell me? Come stop me, come put your finger in my face. It won’t be the ending you want.

“[When I said ‘there’s only five rappers busting in Atlanta’] that was one of those things where you and I know who I am talking about. Me and my nigga Killer Mike had a discussion in the Stankonia studio, right around the time we were doing this record called 'Ready, Set, Go.' It was like, ‘For real, me and you are the only ones who are really repping the town and kicking some lyrics.’

“So when I said it in a rap, he knew what I was talking about. But, everyone else was like, ‘Who are the other four rappers?’ Killer was like, it was slick how you did that. It was well played. But me and Killer have that relationship, he still calls me. He sees things in verses and lyrics, he sees double entendres and metaphors and similes and analogies that go over other motherfuckers’ heads. He would call me and say, ‘Hey, slick how you did that young nigga.’”

DJ Toomp: “Just from him calling himself the King of the South, a lot of the pioneers wanted to see what all of the riff raff was about. When they met him, it ended up being a great relationship. So the man’s Rolodex got a lot bigger off of him calling himself that. He was able to call Pimp C when he felt like it. If he hadn’t called himself that and just came out as a regular rapper, he would have never attracted so much attention from the pioneers. Just calling himself that made everybody come say, ‘Let’s see what this lil’ nigga is talking about.’”

Bun B: “I probably felt the same way some of these rappers are feeling now with Kendrick calling himself the King of New York [as I did with T.I. calling himself the King of the South]. We reached out to him and had a talk about it. He explained that he was trying to make a statement and carve out his niche, it wasn’t necessarily meant so much as a disrespect to the people that came before him but more a word to send out to those that were coming after.

“Initially people might’ve felt a certain way but again, it’s the same thing that Kendrick did. It made a lot of people from the South step their lyrics up to try to prove him wrong. Like, ‘I’m making this statement, this is how I feel, if you don’t believe what I believe about me then come and prove me wrong.’ It was never a title I aspired to have. I wasn’t necessarily worried about the South, I wanted to be the best at everything over everybody. I wanted to be the king of everything.”

Jason Geter: “If you look at the artists that were around in Atlanta prior to this, everyone followed a blueprint of what Dungeon Family and OutKast were doing. Then Lil Jon came along during that time with the whole Crunk movement—so people followed that. Tip was the young, arrogant kid in the city that wanted to start his own branch on the tree.

“When he came out and said, 'Hey, I’m the King of the South,' truth is a lot of people had a problem with that. So he didn’t get help from certain people. It was frustrating for him because the guys he looked up to didn’t embrace him just because he said, 'I’m the King of the South.'

“Whereas an artist like Ludacris that was doing his thing—but wasn’t doing it in a threatening way—was embraced by a lot of the older rappers. King of the South was something that he threw out there as a goal to reach and something to live up to. Tip was definitely going through the things and trials and tribulations within himself like, 'I gotta prove to the world that I’m worthy.'

“More than anything, you want the co-sign of the people that you grew up listening to. Tip was all about UGK and OutKast. Those are the first cosigns or nods of recognition that you looking for. During that time, Big Boi was the shit in Atlanta. Dre’s always been Dre, but Big Boi was like the guy that was in the streets.

“Those looks, those offerings or extensions of hands, he didn’t get that. There were some artists that he noticed like, 'Damn, they’re getting that?’ It was kind of like a blessing in disguise because that’s really how Grand Hustle all came about. That whole process was saying, 'Fuck everybody else. Let’s continue doing what we doing.’

“It’s so corny. I forget the name of the record, but we were in the studio and he recorded this track with Mystikal. He did a hook for the record first and Mystikal said, 'Alright, I’mma let you do a verse for the record, but if you outbust me, I ain’t gone keep you on the record.' Tip did his verse and Mystikal was like, 'I’m not gonna keep you on this record.’

“You want the nod from Pimp C. Tip loves Pimp C. Bun B was on the album. Pimp C, I don’t know if he was locked up during that time or what. It wasn’t a bad blood or a loss of love. We all got to know Pimp C and accept him for the guy he was. Put yourself where Pimp C was at. During that time, Pimp C didn’t wanna be on the 'Big Pimpin’' with Jay Z.

“I remember seeing Pimp C at Stankonia Studios right around the I’m Serious time. He was like, 'I ain’t got time for that.’ For Tip he was getting used to this. People get in and they think that everyone’s friendly with each other, like it’s one big fraternity. Once you get in, you start to see the realities. That was eye-opening for him as well.”

Sanchez Holmes: “Tiny sang the background on that. Nobody knows that she’s the one humming “ah’s” in the background. That’s me playing the guitar on that shit too, man. That’s when I was starting to feel good about my hard work. I had someone that actually gravitated to my sound and fucked with it. That made me excited about doing it so I was being more creative.”

"Be Better Than Me"

Producer: Sanchez Holmes

T.I.: “Me and my partners, we were really young and thugging. For me to become a rapper after the life that we lived, they would laugh at me at the time. In the hood where we were from, a lot of independent motherfuckers had a little money. We would beat them up in front of their girlfriends, cause that was just us.

“In the past, I have let other people dictate mine because I’ve gotten angry. I said, ‘What? I’m on my way!’ [Laughs.]. Those times, before I had the power to move mountains. When you have the power to move mountains, you don’t drop it on somebody. I’m getting older. I know I can move these mountains. Why would I exert the energy to do that shit?”

Sanchez Holmes: “Anyone that know the album Trap Muzik know that it’s a real diverse album. My energy with Tip was more of a positive energy. We had our grimey stuff too, but for some reason every record that we did, it was more on a positive side. When I got that opportunity [to work with him] I tried to step into his world more than bring it into mine. He’s adaptable.

"I had that sound that was more soulful. I tried to give him some diversity with my work. ‘Be Better Than Me’ was one of those feel good moments, where there was a light at the end of the tunnel. Like, you need something to reach for, if you ain’t got no goals, try this out. Don’t try my route, get your own and do it better than I did. It’s self explanatory.”

"Long Live da Game"

Producer: Sanchez Holmes

T.I.: “I was still living that lifestyle [before the album]. I was on probation then. My manager Jason Geter challenged me to step out on faith, to not live the life that I was living before. If something bad happened, I would have all the opportunity to take it away. So I was like alright, cool. Right then, I got a record deal and things started paying off. It’s been popping ever since.

“So many people depend on me for their livelihood. I was literally the determining factor between living free versus living a continuum of that lifestyle. I was the only one who could take a shot when the clock was running down, and win the game not just for myself, but for everybody, and more.”

Sanchez Holmes: “The whole story in that song, it’s so blatant. You can listen to that record and it’s almost like watching a movie. He appreciated the music that I was doing. I appreciated his creativity because he was turning my beats into flowers.”

After The Album

T.I.: “We all felt so fortunate. We were so blessed and so thankful that we were doing what we loved. People were accepting us, our sound, and our philosophies. We were representing the city the proper way and we were having fun. That year for me was the beginning of the rest of my career. That had to happen for all these other things to become a possibility. We were ecstatic.

“Nothing can ever replace [the disappointment I felt after I’m Serious]. All the success in the world won’t take away from that, from having your hopes up and knowing that this is supposed to happen, knowing it’s your time, and then being wrong. Having to pick things back up and continue to push. All the success of today will never take away that hurt. But that only contributed to all that we’ve been able to accomplish from then on.”

DJ Toomp: “I still play Trap Muzik in my Porsche. I listen to Jeezy’s Recession, Nas’ Untitled, Trap Muzik, and J. Cole’s Cole World when I'm riding in my sports car.

“That was one of the real concept albums out of the South. Like, Ice Cube’s AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted was a conceptual album. Dr. Dre’s The Chronic took you on a journey through the West Coast. After you heard those albums, you felt like you went on a tour through the West Coast. With Trap Muzik, we took people on a journey through the Southern traps. The lingo, the type of stuff we wear, the jewelry, all that. A lot of songs, everybody around the country could relate because it was like, ‘Wow, we’re doing the same thing in our city but we never called it trapping.’

“We cracked the doors open. That made other cats living their lifestyle feel more comfortable about getting on records. Nowadays, you hear references made about any type of street activity being edited, they’ve caught onto the lingo. We actually got away with a whole lot of stuff then. A whole lot.

“People are calling some of this new stuff I'm hearing—this EDM stuff—they’re calling it ‘trap.’ There’s no subject matter about trap, it’s just a beat.’ It’s really not trap beats, it’s just dance music using our 808s and our drum patters. I was like, ‘How can y’all call that trap? What’s trap about that? There’s no lyrics to it.’ When they reword and retitle things it can throw me off, just being from the old school.

“We used to base our stuff off of what the East Coast was doing, which is the mecca. Now, they’ve started to pay attention to what we’re doing. You can’t even tell where an artist is from on a record. It’s a trip now.”

David Banner: “The thing that I liked about Trap Muzik the most is T.I. was able to put a face to a lyrical aspect of Southern music without trying to be like anybody else. It put a voice to the emotional aspect of Southern music. Most people don’t give Southern music the credit for emotion. Everybody from every other place is so caught up in the lyrics.

“T.I. was able to get that emotion from Southern music, but articulate it clearly. A lot of times, people say that Southerners are not lyrical, but that’s not the case. A lot of times, people just don’t understand what the hell we saying. T.I. was able to articulate himself without losing that Southern edge.”

DJ Drama: “This was his Reasonable Doubt. Atlanta was a big part of the culture already, but by the time Tip took off, he opened that door for Jeezy in ’05. By 2006, Atlanta was a mecca of rap music. He really came into his space on King, but the T.I. fan that’s been a T.I. fan for quite some time is always going to resort to Trap Muzik. As artists, we don’t like to hear this, but I’m sure Tip gets people saying, ‘Yo, we want that Trap Muzik T.I.’”

Bun B: “The album let people know that he was a force to be reckoned with. He let people know that he wasn’t going anywhere. I’m proud of how far T.I has come in his career. He was adamant about what it was he wanted to achieve and who he wanted to be. As far as I can tell, he did everything he said he was going to do.”

Sanchez Holmes: “He was getting a lot of respect out there in the streets [when we were touring] because we wasn’t doing the arenas yet. It was big to see how the people gravitated to him and loved him. That album changed my life. I love my brother. [Laughs]. Shoutout to Hustle Gang. Grand Hustle for life, believe it.”

Jason Geter: “[We were touring for a while and] I remember coming back to Atlanta. We booked a show at a club called The Bounce. It was off Bankhead and it was a notorious club during that era. Going to the show the traffic was crazy. It was one of those defining moments like, 'Wow, this is all going to The Bounce? We finally got into the club and the club was packed wall to wall. That was one of those moments like, 'Wow. This shit is about to be on.'

“[Later on] during that Jay Z and R. Kelly tour, after R. Kelly fell off the tour, Tip did like a bunch of dates with Jay. Seeing Tip at Madison Square Garden on stage with Jay Z, that was like, ‘Wow, this is like a national thing.’ Like, this shit is all the way for real. After seeing the frustration to seeing him be embraced by some of these guys that were where you want to be... It was a long time coming.

“I’m proud of what we accomplished. It wasn’t given to us. Everything we got, we had to go out there, we had to fight, we had to shake trees. Grand Hustle was basically launched all from Trap Muzik, so even like the 10th anniversary of Grand Hustle, it started with Trap Muzik. That’s my favorite album, not necessarily so much because of the music that’s on the album, but because of the story.”

Sanchez Holmes: “That’s when he became the King of the South for real.”