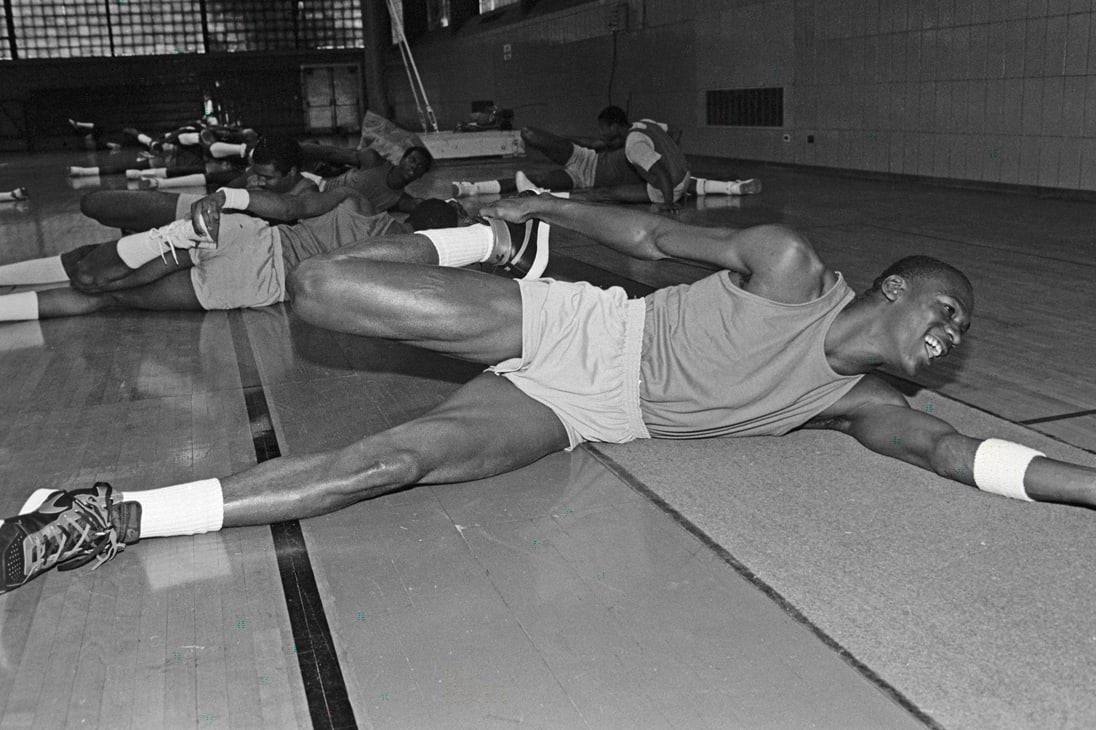

Where did Nike, a brand that was barely relevant in basketball in the mid-1980s, find the foresight to go all-in on signing a young Michael Jordan and make him the star of their lineup of basketball sneakers? How could the brand possibly have foreseen that Jordan, who was already accomplished but had yet to play a game in the NBA, was worth its entire marketing budget? And who convinced the reluctant Jordan, who at the time preferred Adidas, to sign with Nike? It depends on who you ask.

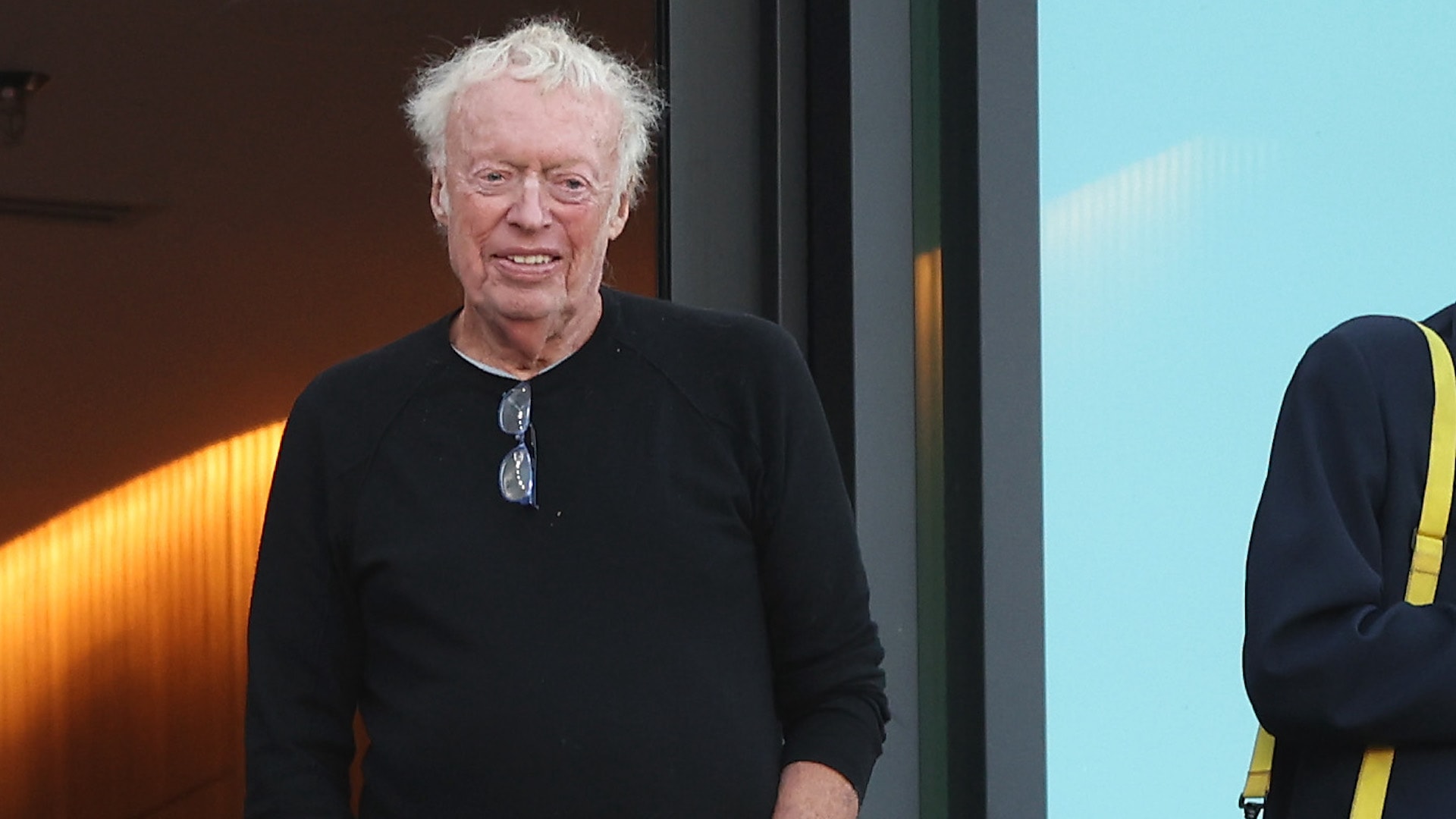

The question of who deserves the most credit has been contested by aging sportswear execs for years. For now, the most definitive answer comes via Air, the Ben Affleck and Matt Damon movie released this week that tells the story of Jordan’s signing to Nike in 1984 and the creation of the Air Jordan sneaker. It centers on the efforts of Nike exec Sonny Vaccaro (played by Damon) as he persuades CEO Phil Knight (played by Affleck) to bet big on Jordan.

In the movie, Vaccaro is the protagonist, the one who identifies Jordan’s potential and champions him within the walls of Nike. The real-life Vaccaro, who bounced to Adidas and later Reebok after being fired by Nike in 1991, has long held that he was instrumental in bringing Jordan to Nike.

“This does not happen—this isn’t self-glorification—if they don’t invite me to the meeting. The world changes,” Vaccaro said in a 2021 interview with Complex, recalling his role in signing Jordan. Vaccaro has, sometimes bitterly, held on to the narrative that he was key in turning Michael Jordan into Air Jordan.

But Nike execs, and Jordan himself, have said otherwise.

In 2015, when ESPN ran a 30 for 30 documentary on Vaccaro called “Sole Man,” some of the men involved in the Air Jordan deal begged to differ with Vaccaro’s telling. In a USA Today piece that year, Knight, Jordan, Nike exec George Raveling, and original Air Jordan designer Peter Moore offered their sides of the story. The Nike affiliated among them downplayed Vaccaro’s role.

Nike became a powerful brand, one that resonates deeply with consumers across generations, partly because of how early on its leadership understood the value of storytelling. The way Nike retains tight control of its stories (who is allowed to tell them, what is the company’s official version) helps the brand manage how it’s perceived. Usually Nike is successful in this—much of what we know about Nike was told to us by Nike.

With the release of Air, which favors Vaccaro as a hero despite years-old protest by the most powerful men at Nike, the brand has lost some grip of its legend.

It is the first major movie about Nike’s history, and its telling of the events, rather than one carefully crafted and maintained by the sneaker company, will be accepted as fact for a general public that doesn’t care to sift through the different versions floated through the years. It is a rare moment in pop culture when Nike’s story isn’t being told by Nike—the company is not associated with the movie in any official capacity.

Screenwriter Alex Convery was motivated to write the movie amid the hype around The Last Dance, the ESPN series about Michael Jordan that captivated audiences at the onset of coronavirus lockdown in 2020. The episode touching on Jordan’s sneakers struck him, and he went deeper into the story.

From there, Convery landed on Vaccaro. He had a connection—after college, Convery worked as an assistant for a producer who worked on “Sole Man.” The screenwriter met with Vaccaro to hear his story in more detail and get feedback on the script.

Vaccaro was actually interviewed (for hours, he said) for The Last Dance, but not featured at all. The omission, he said, broke his heart. The presumption was that he was cut because the Nike-aligned Jordan, whose recollection of the events is different from Vaccaro’s, was involved in the production.

“It’s done because of animus, it’s done because of ego,” Vaccaro said in 2021. “It’s done because what I did was go against them.”

If The Last Dance cut him out where “Sole Man” celebrated him, then Air (the three projects share personnel) gives the editorial perspective back to Vaccaro, who is listed as a consultant.

Affleck, who directed Air, says the movie is not concerned with pinning down the exact history of who did what for the Jordan deal; it is not a documentary nor a biopic. And though the movie hews to Vaccaro’s telling of the events, the director did take input from Michael Jordan on who was important to the story.

He hasn’t divulged all that Jordan told him. “A number of things, and I’m not sure that I’m at liberty to share every single one,” is how he responded to one question about what Jordan wanted in the movie. In press runs for Air, Affleck most often cites the inclusion of Jordan’s mother Deloris, and her portrayal by Viola Davis, as chief among the Chicago Bulls legend’s demands.

Affleck says that Jordan also asked for the movie to feature Howard White, a Nike employee who eventually became an exec at Jordan Brand, and George Raveling, who was an assistant coach on the US men’s Olympic basketball team that Jordan played for in 1984. Jordan’s old comments on Vaccaro—who he said didn’t influence him to go to Nike—gave praise instead to Raveling.

“He used to always try to talk to me,” Jordan told USA Today in 2015, “‘You gotta go Nike, you gotta go Nike. You’ve got to try.’”

While Jordan’s mother and White are integrated into the story well, the appearance of Raveling in Air is brief and feels tacked on, more a concession for Jordan than a piece of the story that anyone who worked on the movie identified as crucial.

That Air was made with the blessing of Jordan, who still makes hundreds of millions of dollars annually from the sale of Air Jordans, allows for some version of Nike’s telling of the Air Jordan deal to seep into the story. Still, while Affleck was compelled to get Jordan’s approval to make the movie, he did not seek Nike’s.

“I did not have a conversation with Nike,” Affleck told the Hollywood Reporter, “because I didn’t feel the same sense of personal responsibility [as I did to Michael Jordan], because it’s not a history of Nike.”

The conversation with the brand didn’t happen until after the movie was made—Affleck said in an interview on Jimmy Kimmel that he screened it in Oregon for a Nike audience that included Knight. Affleck described Knight as gracious and moved by the film.

But the Nike co-founder would have to disagree some with Air’s presentation, which is largely a celebration of Vaccaro. He’s certainly entitled to—Nike’s history belongs to him as much as it does to anyone else. In 2015, Knight said that Vaccaro helped but was not the MVP in bringing Jordan to Nike, and that Moore and Rob Strasser, then Nike’s marketing director, were more important in the process.

“Of course, you got a lot wrong,” Knight told Affleck after seeing the movie.

The broad history of the movie is accurate enough, but there are things for sneaker obsessives to nitpick. This is a necessary procedure—the movie couldn’t exist without the support of hyped-up consumers who made Air Jordans legendary by buying them year after year, so it’s only fair it be judged by the same crowd.

These collectors have upheld some Nike fables over the years and cut down others. Nike told them for decades that when Jordan first wore the Air Jordan 1, the NBA fined him for its bold colors. The brand turned the dispute into an ad campaign that made the shoe even more desirable.

But the first infractions actually happened when Jordan wore a black and red Air Ship—not the Jordan 1. It wasn’t until after sneaker diehards like Marvin Barias petitioned Jordan Brand to acknowledge the real history that the company brought back the Air Ship and tacitly admitted its role in Jordan lore. Nike finally embraced the full nuance of the events, but only after an outside entity highlighted them.

How has Air fared so far with those keen on pointing out what is wrong and right about depictions of sneakers in the media?

The scattered complaints about the prop version of the Air Jordan 1 made for the film are excessive; securing a real 1985 pair that would look new in the movie would be near impossible and the shoe that shows up onscreen isn’t so egregious a deviation from the real thing. The lambasting of a vintage sneaker that shows up in the trailer with an Ebay tag from the 2020s still attached is totally warranted, although it’s almost completely edited out in the final cut.

Most of the lead men are too Hollywood handsome to convincingly read as the scruffy guys in Oregon who built Nike. Rob Strasser (played by Jason Bateman) is vulgar in the movie but never as volcanic as his real-life coworkers described him.

There’s a scene where Moore, who designed the first Air Jordan and much of Nike’s early visual identity, asks whether Jordan’s sneaker should be built on form or function. The moment falls just short of letting the character fire off the maxim of “form follows function” that guided the real Moore’s work.

Some Nike alum say that Moore and Strasser played a far bigger part than the movie shows.

In general, Air is perfectly entertaining and at times pretty funny, but it may be a slight letdown for sneaker people. There’s not much pandering to the demographic who lines up for sneakers or obsesses over their provenance. (Nike design icon Tinker Hatfield said he was in an earlier version of the script but later written out.) There are old Blazers and Night Tracks decorating the Nike office, but no real Easter eggs to suggest that the filmmakers are greatly concerned with sneaker culture.

Air will dictate the shape of some of sneaker history, as it’s the most accessible (if somewhat fictionalized) version of Nike’s early years that’s on record. It’s a version that comes mostly from Vaccaro, a man who years ago on the Complex Sneakers Podcast called his erasure at the hands of Nike people the “biggest fraud in America.” Now, he’s been lionized as the man who put the deal together. Air makes him, and Jordan’s mother, the original champions of Air Jordan.

The coup for Vaccaro comes at a cost for Nike, which isn’t in control of the story. Until Netflix’s option for Knight’s memoir, Shoe Dog, comes to fruition, this is how most people will understand the brand’s rise.

Air screenwriter Convery relates the different threads from different narrators on how the Air Jordan deal came together to Rashomon, the Akira Kurosawa film built on characters spinning contradictory yarns from their own subjective viewpoints.

Vaccaro has preferred for comparison John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, where legend turns to fact and prevails in history. He’s called past attempts by Nike brass to write him out of that history as ridiculous.

“It’s indefensible,” Vaccaro said in a 2021 interview with Complex. “They can’t do it.”

Air, which smudges fact, legend, myth, and memory, makes sure of that.