After Nike unveiled the grand finale of its pre-Olympic exhibition at the Palais Brongniart in Paris last week, pulling up a screen to reveal 13 avant-garde sneaker prototypes designed using AI tools, Travis Scott was the first one onstage. A voice on the loudspeakers had invited the audience to see the prototypes—wild designs sat on pedestals and enveloped in the gentle storm of a fog machine for dramatic effect—up close. Following the rapper’s lead were Nike executives, a handful of its top collaborators, and a crush of eager media hoping to capture the first crisp images of what was being touted as the future of footwear.

It was an emotional evening for Nike Chief Innovation Officer John Hoke, who led the teams that designed the group of otherworldly models onstage.

“My heart was full last night, to be honest with you,” Hoke said the next day. “I know what it took to do this.”

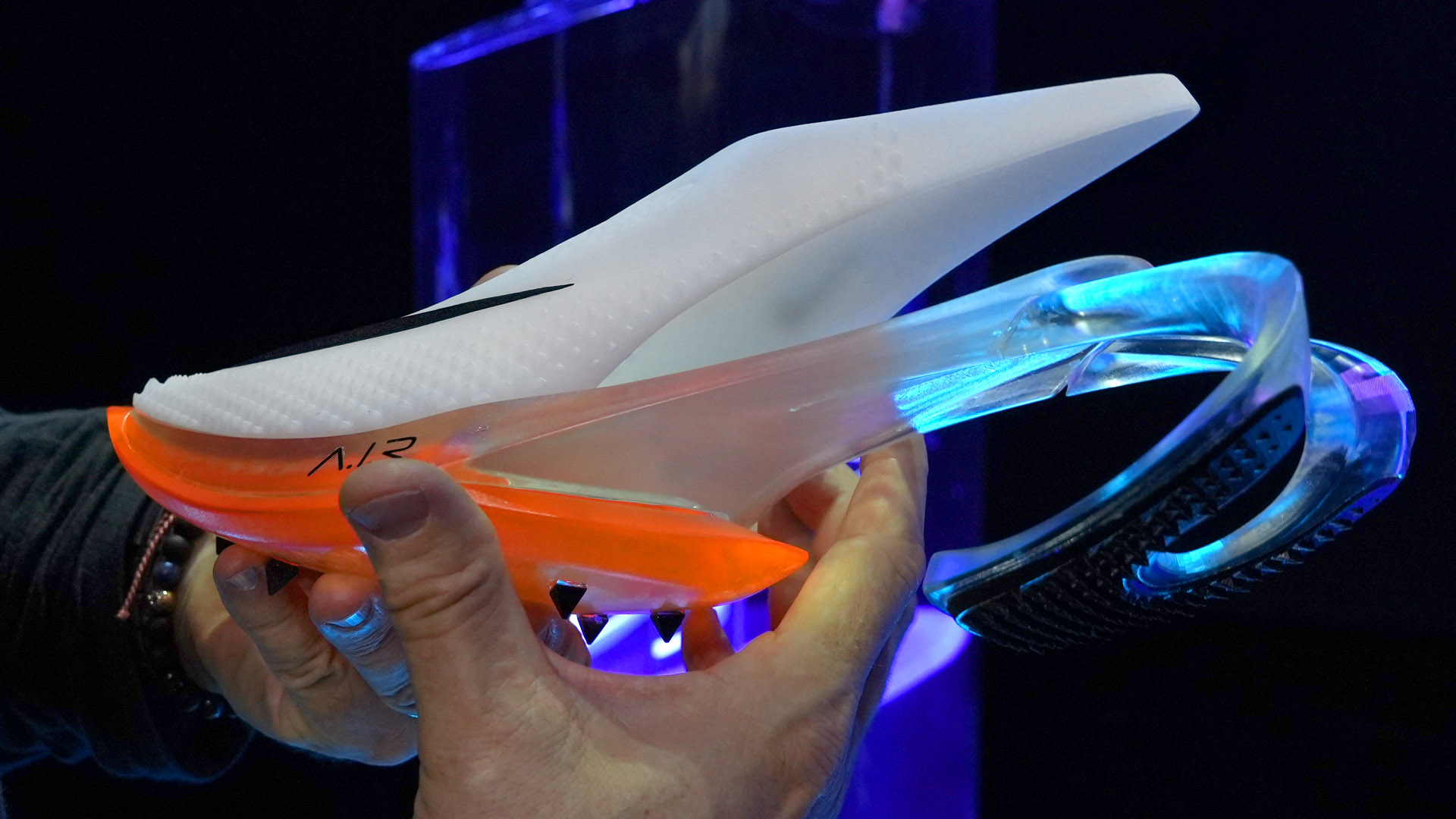

The designs shown in Paris comprise the first wave of output from what Nike calls A.I.R., for “Athlete Imagined Revolution.” They are best understood as concept cars, not shoes that can be worn in their current form.

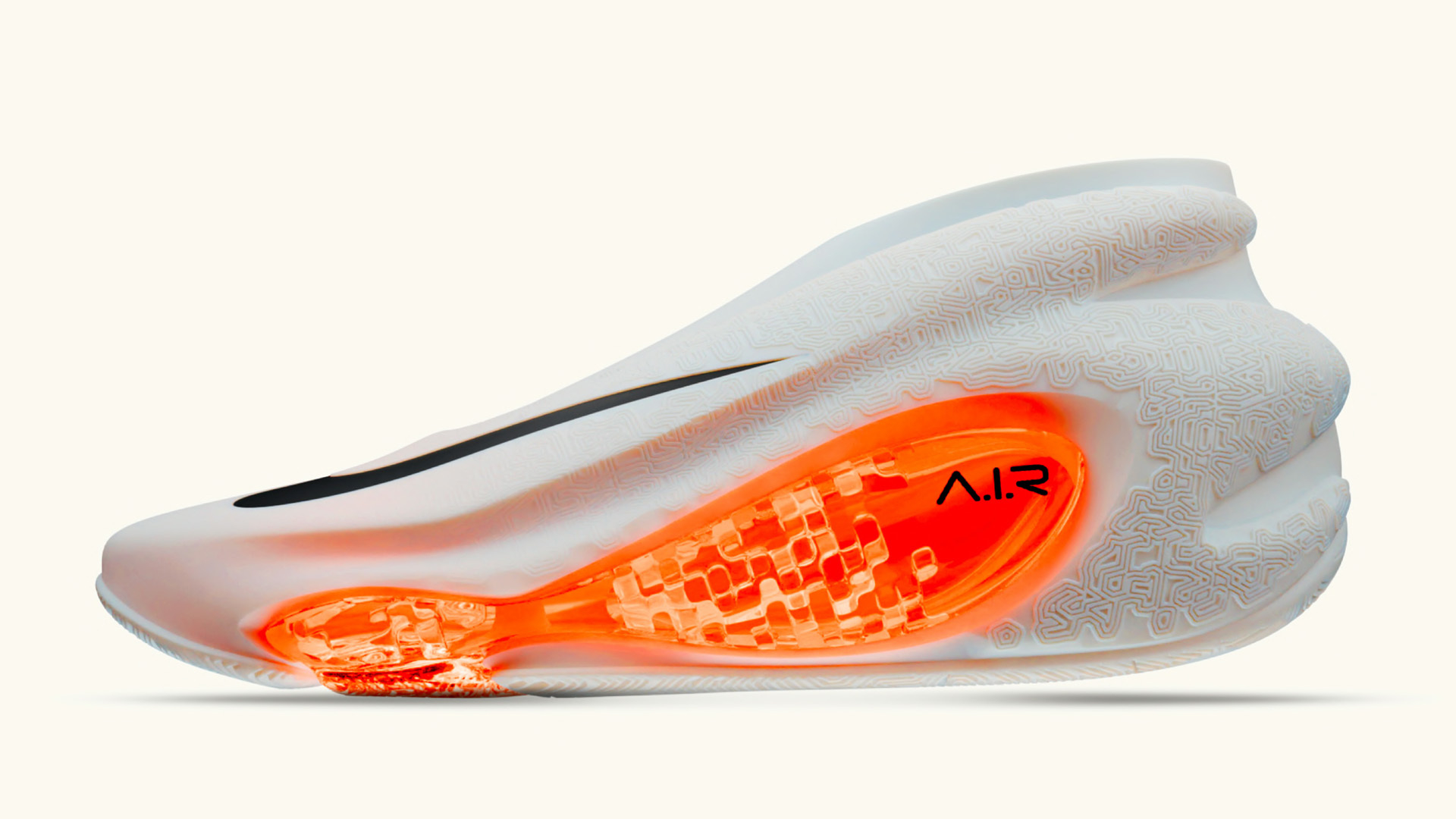

Nike describes A.I.R. as a co-creation process through which athletes like Victor Wembanyama and Sha’Carri Richardson work with Nike, using tools like AI and VR modeling, to make products tuned to their every desire. This pitch puts A.I.R. next in the lineage of Air, the famous Nike cushioning innovation that’s been a fundamental tech for the sportswear giant since the end of the 1970s.

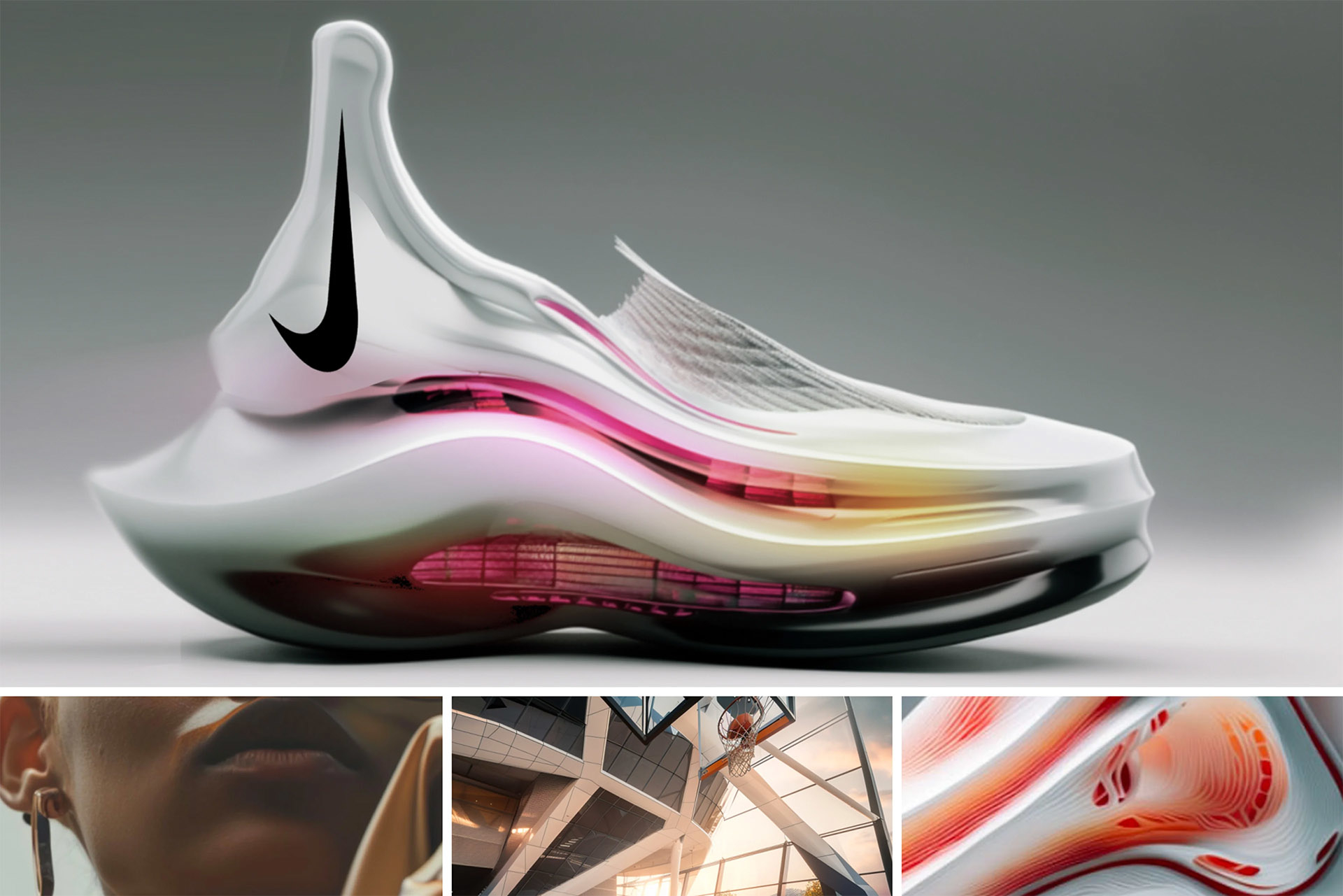

The A.I.R. footwear prototypes look like they were beamed in from a different galaxy. Wembanyama’s is a hulking, rolling, vaguely foot-shaped slab etched with a maze of fractals. The silhouette for A'ja Wilson is interrupted in the middle with a series of slits that are meant to dilate when she goes left. The A.I.R. prototypes are rendered in a soft lunar white, with orange accents that seem to glow. Some look like intergalactic weaponry, others like the fossils of Pokemon.

Most of them look like nothing else in sneakers right now. Nike needs that.

The brand has been criticized in the past few years for relying too much on retro styles rather than the kind of innovation it’s so keen on boasting about. Consumers and analysts alike feel Nike design is becoming stale.

With calls for genuinely new product mounting, Nike execs have recently promised an “innovation supercycle.” A.I.R. (and Nike’s Olympic presentation in Paris as a whole) is part of that. Nike needs to show the world it has a real vision for what’s next. Hoke knows that.

“It's such a source of energy for us to demonstrate and to believe that we are the leaders,” said Hoke. “We set the pace for this industry, and to get back on the front foot and show what's possible, to show our incredible teammates and our incredible athletes.”

If shoes as fantastical as the A.I.R. concepts are indeed possible, they are not ready just yet. The hypothetical signature models Nike displayed in Paris are more sculptures than sneakers. And it’s hard to tell where they land on the spectrum of fiction to reality, as far as representing something that’s actually wearable. The A.I.R. models in Paris were made of hard, 3D-printed material and couldn’t reasonably house a human foot.

The exception was a tamer (but still bold) design worn by the track star Richardson, who appeared onstage in a new Nike sneaker that features (from the ground up) a giant double-stacked 270 Air bag, a Flyprint upper, and a sheath extending well beyond her knee.

That pair for Richardson, inspired by the A.I.R. group but not technically part of it, offered a more measured preview of where Nike could go next. It is significantly more terrestrial, but still daring. And still what Hoke views as an example of his company leading from the front.

“This is the result of that, and one of my first tests of my new job,” said Hoke, who became chief innovation officer at Nike last November, “and you'll see much more of this coming from our teams.”

Hoke spoke with Complex in Paris about how the prototypes were made, how the athletes were involved, and what it means for the future of Nike. The conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

When did A.I.R. start?

It started earlier this year, in January.

What were those first conversations?

I brought a team of 20 of our top innovators and creators and designers together, and I said, “We have an opportunity here to showcase a new alchemy.” And to converge the athletes' ambitions and dreams, combined with our imagination and our own interests of design, and these computational emerging technologies, to converge those and show a sense of urgency and a sense of opportunity.

As innovation is always about new and better, it's also at times about bringing artifacts from the future forward to present to the world and say, “This is what's possible now, and this is where this is going.” And you get a sense of the trajectory of the aesthetic and the function. So my brief was we were going to showcase functionally advanced product that was going to be fearlessly beautiful and fantastically creative. Those three things—functionally advanced, like, show how we want to take the world and advance functionality, but also advance beauty.

Is that a hard thing, to try and convince people that this is the type of footwear we'll be wearing in the future when we're stuck in our ways?

Yeah, I mean, it's part of my role, to show what's possible and then begin to change the conversation, the dialogue, position both this fearless beauty with this fantastical creativity and believe in it. And then get the teams to say, yeah, we can do this. So the result of the conversation was, we're all in. What this demonstrates is a multidisciplinary focus.

In the room we had our data scientists, our biomechanists, our engineers, our designers, our computational designers, our mind-and-data science designers all converging. And that was the thing that was so powerful about this is you strip away the boundaries of your role and you are possessed to go get a project like this done. I was just saying, the energy that was created from this is, “We can do this. This is a part of the future.” I'm not satisfied with just iterative thinking.

I'm going to be satisfied when I have revolutionary leaps in all the form factoring you see here and the projections of what we think these shoes can help athletes do: give meaningful advantages by fixating on the fractions of inches and spaces. Giving them a true sense of confidence inside of them that they're going to step to the line, the pitch, the floor, and say, “I got this.”

There's been a lot of chatter about Nike not having enough innovation lately. Is this your answer to that?

Certainly a step forward for me in my new job, I think I'll use this as a stepping stone, as a base case of what's possible. I think we have all the talent. We have the world's largest lab, we have the world's best talent, and now we have the world's most cutting-edge technologies. I think these become proof points of, “We believe we can make a difference, and we believe we are here to create the future.”

I think through the pandemic, with all the disruptions of the pandemic, we were serving consumers things that they know and love, which is fine, but part of our job is to take them someplace new, to show them things they don't know are possible. And that was my goal here, was to show the world what's coming. My personal commitment, with our teams, is that as the leader in the industry, born from the spirit of Steve Prefontaine, a front-runner, we set the pace. That's our job. And our job is to get back on the front foot and set the pace.

So we'll leave no stone unturned to demonstrate that exact fact. World's best athletes, world's best imaginative minds, world's best technologies, all being brought to bear. And the show last night was a prelude to the world stage of the Olympics.

How do you bring the athletes in? Where do they come into this process, and how do you convince them that this is what we're going to be wearing in the future?

So, great question. A fascinating part of this process was, when we work with athletes, obviously we listen to them, we study them, we know them, we see the unseen and the unknown through studying them. That results in amazing performance product. This process, this new procedure, balances their performance with their persona. So they're truly collaborative. We’re co-creating with them. So it's not, “Wear this equipment that we made for you.” We did this together; this represents you. So all the details you see in the products are the results of deep conversations with them and having them feel an even more heightened sense of confidence that they were a part of the process. They're the co-conspirator in themselves.

What was it like working with Victor Wembanyama on those shoes?

Getting to know Wemby and his interest in sci-fi and his interest in fantasy and the future.

He's like, the most fitting person you can imagine for this shoe because of all this conversation about him being an alien, and then you have the crop circle commercial. Who better to show the world?

But who knew? And so I think, again, taking the persona and meshing that with the performance is that new ground. It's a completely new territory. And in terms of the storytelling device, it lets all of us know him—not just him the player, but him the person. What makes him tick? What's he inspired by?

How many versions has a shoe like that gone through to get to what we're seeing today?

So in the lightning process that we ran, the way we ran that was there were two phases.

You said the lightning process. What is that?

Lightning fast. Like, weeks fast. There was the initial stage where we were just kind of beginning to think about, “OK, so how do we frame the project? What is the sense of inspiration and how do we engage?” And then moving from that engagement to manufacturing and building.

So what we did differently was bringing the athlete into, in this case a Zoom call, and then inviting them into our artificial intelligence engines and working with them on prompting. So before even showing them sketches, we're just talking to them about abstract ideas. Think sort of a painterly way of discussing an aesthetic, discussing a mood, a vibe, and then prompting right away and showing that. Do you mean this? Do you mean that?

And giving those prompts to an AI program?

To an AI program, yeah, and then of course, seven seconds later you get four images to pick from with the athlete. So right from the beginning they’re, at the outset, involved in the mood boards. It's not just us doing tear sheets—we're creating moods with them.

So the process that we ran was we would ask each athlete to come with 100 images that were inspiring. One hundred images, usually it's hard; it takes a long time. But with artificial intelligence, and the way we did it, it was quick, and then that set the parameters of the mood and the moving from the mood boards, if you will, and the base images of how they felt about Air as they described it.

In Wemby’s case, they talked about sci-fi and fantasy and Predator and the Alien, and then we begin to fuse those together. And then you move from 2D images to 3D mathematics, computational design. We have the world's best computational designers. So we work very quickly; that's why we brought all the little models. Within a few-week process, we moved from 2D to multiple—literally dozens of models. We could show them on the screen, give them the 3D thing to look at in an AR/VR environment so they can move around themselves.

So the athletes are looking at the AR modeling of it?

Our teams are, and then we can have [the athlete] not wear the headset, but watch our designer, and then they can see how we're holding it and moving it. Here's the bottom; here's the top; here's the side view. And so that's such a more intimate way of showing form factoring. Then moving from about 20 models per se, beginning to select the top three. We brought the top three.

So we made up to 25 individual ones to look at, then we culled it down to three, and then getting the athlete back onscreen or in person, showing them and looking and then picking one. Then on top of that one, just obsessing how would we make Air look and feel different in the future.

And then the next big stage was encoding their perspective, their persona, their vibe on top of it. So I'm just looking at Faith [Kipyegon’s] shoe, and she has this fascination with bead culture from her community, her culture. And so if you look, there's a bead texturing along the top of the upper, which she was fascinated by like, “Oh, I talked about that and now I see that.” In the back of the shoe there's a tiny Swoosh sort of hugged by a larger Swoosh, and that represents your child. So those little Easter eggs, those little coded moments are found throughout all those products. And I think that's what really captivated these athletes where it wasn't just, wear this equipment that we made for you; it was like, be a part of this—co-create with us.

The designers, do they have to correct what the AI creates in order to make it a functional piece of footwear? Because I assume that the program doesn't know the limits of actual footwear when AI is designing what a shoe would look like.

Great question. So we used AI in this particular case as inspiration, mood boarding. Think of it as a very crude sketch. But the difference is today it's the velocity, and the fidelity of those sketches are so fast and so good that it gives the athletes like, “OK, no, more in this direction, less in that direction.”

So they're not having to interpret a sketch per se. And then our designers can take it and then they do the sketching process, the hand-sketching process. If I step back, representing on the stage this emergent thought of quantum creativity, where it's the human imagination exponentially faster, exponentially wider. The process that we used, we call phygital—physical, digital.

AI did not design these shoes. It was a big part of the early process that a human ingested, and AI is only responsive to what we tell it to do, and it gives us a glimpse. It's not at all perfect, but it starts the ball rolling, and then the designers come in, the human imagination comes in, and then we're sketching and we're making physically, and we're physically looking in AR/VR, and then we’re 3D printing. To see a sample, it used to take weeks and months, and now it's two hours.

That velocity as a creative, that's why I say it's like quantum creativity. And the last thing I'll say, too, with these tools, is as a designer, it gives you complete parametric control. Every pixel becomes a knot, becomes a placement of a material. As a designer, we love control. So being able to have that parametric control: zoom out, look at it, zoom all the way down and go, OK, there's a little detail there. And I think that was infectious with our teams. That process that will be one of the big takeaways from this show is, you can do this now at a breathtaking pace and with absolute control all the way through the process.

How real are these shoes? These are concepts. Have people worn these? Have the athletes worn them? How much is this a representation?

These are all based on the body scans of these athletes’ lower leg and foot, and then of course studying not just the static shape, but the dynamism of how their feet work. We capture all that in 4D at Nike, and so they can virtually try them on and wear them. None of them have tried these products on in real life, except for Sha'Carri.

We body-scanned her actual legs and feet. What that means is that this fits like a glove, right? So this is a way of taking those samples and being able to quickly make in our innovation center a wearable that she can put on and feel. Now this case, we're putting two large Air bags together. I have one, the other wearable, and there's nothing like it.

So again, this is parametric design. This is quantum creativity. This is actually something we call FlyPrint; it’s 3D-printed slabs.

Some of that was on the second-gen Breaking2 shoes, right?

Exclusively on Kipchoge’s, yeah, and that was designed specifically for his foot. So we're demonstrating that, hey, that is scalable down the road. So there's an intimacy and a uniqueness that we have with these technologies that eventually we’ll capitalize for everybody. The future's going to be hyper-personalization, hyper-customization.

Even for people who aren't world-class athletes?

Down the road, yes.

I think that's one of the biggest questions people have. You've described this as form and function meets fantasy. But people want to know, when can I wear this? When will my shoes look like this?

Stay tuned. Yeah. Form and function meets fantasy is the future, and I think that it leads to this notion of an intimate relationship with Nike that it's not necessarily always aggregated to the mean. Of course it will be, but there will be some step changes that come, technologically and manufacturing-wise in terms of generative 3D-printed capabilities, that are going to let us do things that are unique to you as your fingerprint. More synergistic with you, more symbiotic with your body so that you are not having to conform to it. It’s adaptive to you.

No shoe sizes.

It's an extension of your anatomy, extension of your movement signature, your biology, your anatomy. I think that's coming.