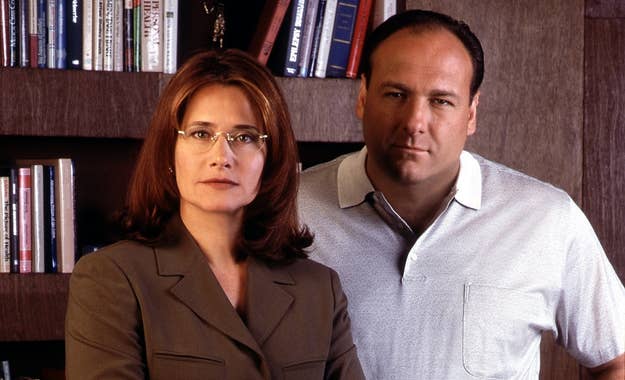

HBO’s The Sopranos celebrated its 25th anniversary last week, so it’s a good time as ever to get off a take I’ve had for years. The Sopranos was a groundbreaking show and a cultural phenomenon when it aired from 1999 to 2007. Recently, it got a pandemic-era streaming bump introducing it to a whole new audience, as well as re-watchers who just can’t get enough gabagool. As someone who has rewatched the series multiple times over the years, something occurred to me between my 11th and 38th rewatch: Dr. Melfi (played by Lorraine Bracco) is an avatar for the audience.

There’s a running joke amongst some Sopranos fans that they just skip the Dr. Melfi scenes. Those people have it all wrong. It reminds me of fans of The Wire who say they skip Season 2 because The Docks plotline is “boring,” as if it didn’t give us Frank Sobotka and The Greek, or Breaking Bad fans who hate Skyler White more than a Nazi who shoots a child. The therapy scenes in The Sopranos are vital, and I’m not the only one who thinks so.

“I think those scenes made the show,” said the late James Gandolfini, who played Tony Soprano, in a 2004 interview, when asked about the Melfi scenes. “They were kind of like the ancient Greek chorus, which allowed the audience to experience what the character was experiencing. I think these scenes let you into Tony’s head, bringing him a little closer to the audience.”

This is why I suspect there’s a different reason people don’t love Dr. Melfi: She is us and we are her. The relationship she has with Tony mirrors our own relationship with him. Dr. Melfi meets Tony for the first time in the show’s opening scene, it’s also the first time we meet him. She doesn’t need a cutscene to know he’s lying when he assures, “We had coffee”; she knows he’s a mobster, just like most of us who knew it was a show about a mob boss before tuning in. At the end of Season 1, as Tony’s war with Uncle Junior heats up, Melfi is forced into hiding. As the show goes into an off-season hiatus, so do her sessions with Tony. We both stop seeing him every week.

As the seasons progress, the therapy scenes are the ones where we really get to know Tony. As he bitterly notes about psychiatry, “Apparently what you're feelin' is not what you're feelin', and what you're not feelin' is your real agenda.” I suspect that creator David Chase’s real agenda with the therapy scenes (aside from the fact he also went through years of therapy to deal with issues with his mother) is to funnel commentary about the show’s relationship to its audience. A well-off professional, Melfi is the exact type of person who’d pay for an HBO subscription in the 2000s.

In another meta moment, Tony calls out Melfi’s fascination with him, noting most professionals would walk across the street to avoid someone like him, but not Melfi. Like her, we enjoy the voyeurism Tony offers us. During a session with her therapist and colleague Dr. Elliot Kupferberg, she confesses as much, saying she’s both thrilled and disgusted by what she might hear from Tony. Again, she is describing us. The Sopranos is enthralling, but it can also be downright nasty to watch a stripper beaten to death or heartbreaking seeing your favorite character get the Miller’s Crossing treatment in the woods. Kupferberg and his oversized water bottle is no one’s favorite, though his initial dismissal and later prodding interest in Tony reminds me of my own father, who never watched the show (he hates on screen violence) but was keenly aware of the hype around it and would always ask me about it.

Mefli’s family life enables another layer of commentary and criticism. Her ex-husband, Richard, pontificates about the Italian-American stereotypes that wise guys like Tony Soprano proliferate. While it’s largely forgotten now, Richard’s condemnation is identical to real-life disapproval from some Italian-American groups in the early 2000s. Meanwhile, Dr. Melfi’s son, Jason—whose smart aleck responses are reminiscent of Meadow—embodies the show’s defenders.

In another scene with Jason, Dr. Melfi has an outburst at a restaurant with a smoker. She’s clearly emulating Tony, who we’ve seen expertly manhandle restaurant patrons. Gandolfini’s charismatic performance has this same influence on many viewers. As any Sopranos fan will tell you, once you get into the show, you’ll never eat cold cuts out of the fridge, walk around in your bathrobe, or flip out when the delivery guy forgets your motherfuckin’ goddamn orange peel beef without thinking of Tony ever again.

The most harrowing Mefli plotline occurs in the Season 3 episode “Employee of the Month,” when she is brutally raped. In sessions with Kupferberg, after the police let her rapist go on a technicality, Dr. Melfi flirts with the idea of sticking Tony on her attacker. This is the ultimate Melfi moment: The audience is tempted to root for her to follow through. This is the fantasy of having a Tony in your life.

I speak only for myself when I say this, but if someone got away with raping my wife/daughter/mother/sister and I happened to be friends with Tony Soprano, I, too, would make a humble request to him on the day of his daughter’s wedding. Let’s be honest though: Most of us are more like Melfi’s sheltered ex-husband, who never killed anyone and doesn’t have the balls to live the life Tony does. There are, of course, many moments where Tony physically intimidates Dr. Melfi, terrifying her. This is the reality of having someone like Tony in your life.

The theory of Dr. Melfi acting as the audience stays true until the very end. After being chastised by her colleagues for continuing to treat a criminal sociopath she suddenly cuts Tony off in the penultimate episode. Fans on Reddit even questioned why she ended things “so abruptly.” Perhaps Chase was telegraphing a hint to the audience, because the same exact thing has repeatedly been said about the show’s iconic, controversial finale—the show ends abruptly.

In their last session, Melfi grumbles at Tony as he covers subjects they’ve covered many times. She sounds like a fan who’s grown weary of the repeating plotlines, a new season with a new mistress that’s just like the old mistress, a new enemy for Tony to kill, a new wrinkle in family dynamics that echo the old wrinkles. It was time to end the sessions because it was time to end the show.

The show lives on, but the golden age of complex television narratives it ushered in might be dead. As David Chase recently lamented: "Audiences can’t keep their minds on things, so we can’t make anything that makes too much sense, takes our attention and requires an audience to focus.” The avatar for today’s audience isn’t an intently focused therapist, it’s someone half-listening while glued to their phone.

As beloved as The Sopranos is, I understand many fans don’t appreciate the meta-commentary the Dr. Melfi character provides. Most people are more entertained watching the crew busting balls or plotting hits. They probably think of the therapy scenes the same way as Tony, like taking a shit. Though, like Dr. Melfi, I prefer to think of it like childbirth.