Lakeith Stanfield once deemed classic Batman villain The Joker a heroic figure, saying, “He makes you have to look in the mirror and flip everything on its head and make you have to laugh at everything that you thought was sacred.”

Indeed, America loves its antiheroes—figures who demonstrate that the good-and-evil binary is simplistic, and humanity isn’t as pure as most moralists would like to believe. They reflect societal conditioning in a violent, individualist country that subsists on racial and class division, obliterating flag-saluting ideals like “all men are created equal.”

The Sopranos creator David Chase and Breaking Bad’s Vince Gilligan bypassed cookie-cutter good-and-bad binaries to create three-dimensional protagonists who subverted the traditional TV experience and had many people rooting for the bad guy, despite how deplorable their actions were. Tony Soprano and Walter White were characters who expressed moral qualms about their actions, but had become too bound to their institutions to correct themselves. They concluded that the ends justified the means, so they hurt innumerable people, put their families through undue stress, and may have misspent their lives. But nevertheless, these men have become regarded as tragic heroes.

This moral ambivalence extends into support for real-life figures who have us looking in the mirror, wondering what our admiration for them means about our moral compass. From Woody Allen to Floyd Mayweather, there are a slew of pop culture icons who’ve done things that negate their accomplishments in the eyes of many. The people who revere these men so often ignore their alleged victims, washing them away in a deluge of pathos and over-contextualization—if they even choose to believe them.

That circumstance is rife in the music world, where artists like Chris Brown, Dr. Dre, and others are still revered despite their documented abuses. There are artists whose music must be compartmentalized from their mistreatment of women to even stomach, but then there are those whose abuses and legal troubles are baked into their music and personas.

Many people can relate to feeling as “lost” as YoungBoy Never Broke Again recently admitted to being on live stream, or like they’re Dying to Live, as Kodak Black expressed on his critically acclaimed 2018 album. They’re two men seemingly bound to the institution of anti-Blackness, whose music grapples with the challenges of becoming more than what racism projected for them. They express the confusion of what it looks like to be a productive member of a society that resents you. In that manner alone, they are relatable figures to many. In a vacuum, their resilience, like that of any artist who defied the odds of systemic oppression, is admirable. But they didn’t get away from poverty without trauma that’s still hurting people. Both men have been accused of committing abuses against women, including Kodak’s open rape case.

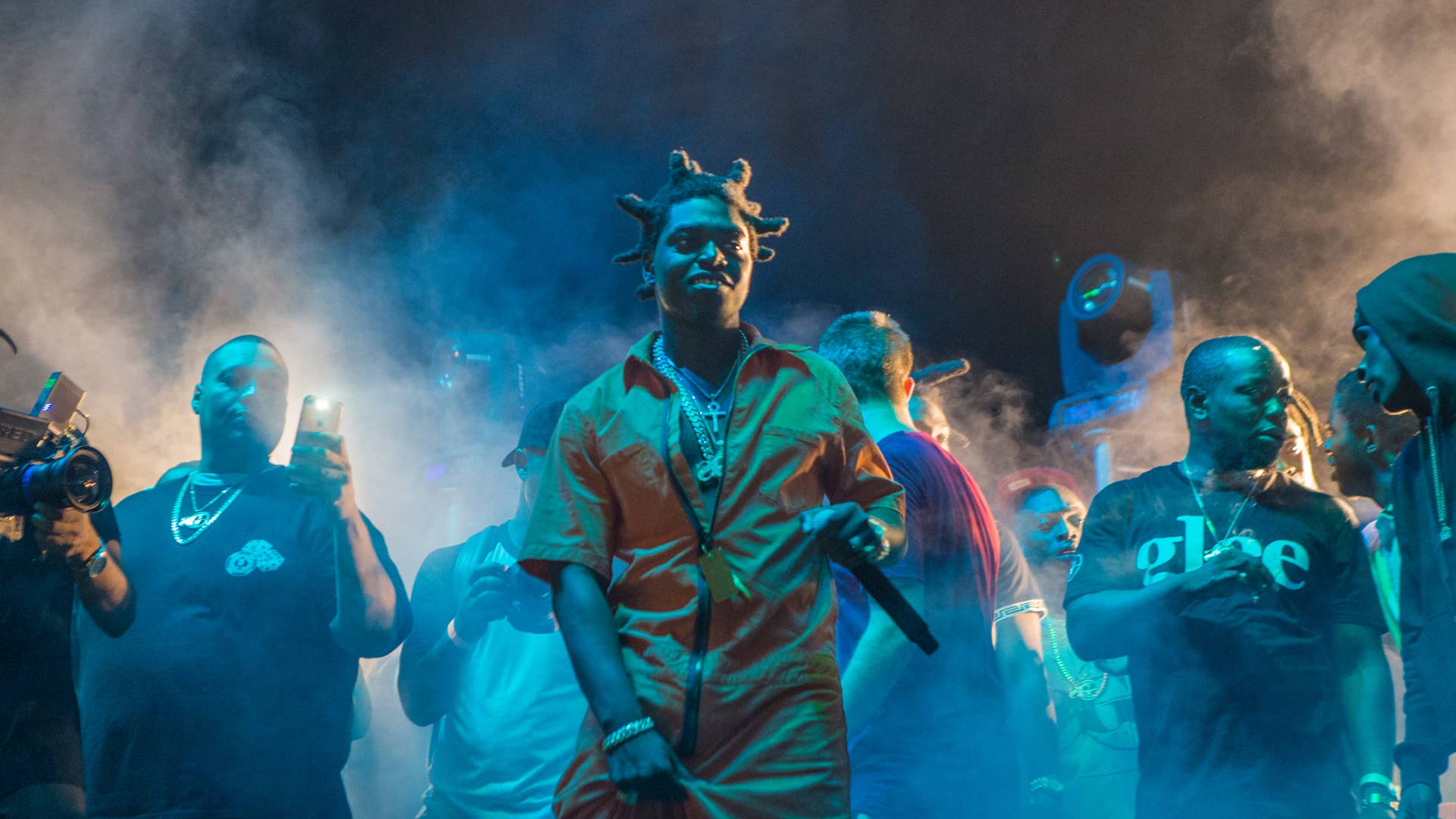

The Florida star was recently pardoned by former President Trump and came home to a hero’s welcome. His come-home track was called “Last Day In,” but that might not be the case, given that a South Carolina woman accused him of assaulting her when she was in high school, and the rape kit reportedly corrorobates her account that he bit her while committing sexual battery. Despite that repugnant accusation looming over him, his fans have ignored his legal trouble, at most lumping that legal woe into a pot of others and merely branding him as a talented, troubled kid trying to find his way. That’s a more sympathetic take than “accused rapist.”

Similarly, YoungBoy was caught on camera assaulting his ex-girlfriend Jania Meshell in 2018, but few of his fans acknowledge that he’s never expressed any accountability for that. He and his crew have been accused of so much violence over the past several years that those actions seemingly meld into an ongoing pattern of misconduct. But that mindset serves neither man, as evidenced by YoungBoy’s recent arrest.

The people who revere these antiheroes so often ignore their alleged victims, washing them away in a deluge of pathos and over-contextualization.

We love antiheroes and complicated figures, and can acknowledge the ways in which the system preys on young Black men, but as long as we pretend that their upbringing completely stifles their agency, we allow them to avoid accountability for their actions. To be “complicated” is a patriarchal privilege. When Cardi B or Azealia Banks admit their past misdeeds or act out on social media, they aren’t contextualized; they’re policed.

Men receive more space for nuance and to be sympathetic figures in public, which means the plight of women is so often explained away when discussing their actions. Similar to the way that moralizing characters in TV dramas are seen as thorns in the antihero’s journey, those who look to hold these men accountable are seen as haters or even agents of conspiracy. But these young men need the cold truth more than to be romanticized. The justice system doesn’t see tragic figures; it sees statistics. How will they be made to realize this when so few of their peers or fans even acknowledge the problem?

Today’s artists aren’t the first young, polarizing musicians bound by the consequences of institutional racism. Few were more aware of their own plight than Tupac Shakur, the mercurial superstar who once noted that he “diagnosed” thug life. But more than calling out the symptoms, he fell prey to them himself, with numerous assault and shooting-related arrests over the course of his career. His most notable brush with the law was when he was sentenced to 18 months in prison for a 1994 forcible touching conviction after a woman accused him and two friends of assaulting her in a New York hotel room.

It’s worth noting that if this incident occured during today’s social media moment, with more people demanding accountability for sexual assault, he’d be an even more polarizing artist than he was back then. But many people dismiss that case in part because of all the other things Pac represented. Along with all that trouble was an artist with a radical Black Panthers upbringing who sought to unite Black people against white supremacy and affirmed women’s importance with powerful records like “Dear Mama” and “Brenda’s Got a Baby.”

The perception was that these poignant records displayed the multitudes of a goodhearted person who wasn’t yet mature enough to rise above his circumstances. In an oft-shared clip of Tupac speaking outside of his 1994 trial, he essentially explained himself to his detractors:

”My whole life has been turned around. I lost every job, I lost everything, every opportunity I can get. Can’t buy cars, can’t get rent, can’t get none of that. But I’m still a survivor, you know? I’m still coming to court. Still smiling, still signing autographs, but soon I’mma go crazy! You know what I’m saying? And it’s up to the world, you know? America eats its babies. No matter what y’all think about me, I’m still your child, you know what I’m saying? You can’t just turn me off like that.”

He spoke for millions of Black people cannibalized by the system, which is why so many deified him in return. He is, for better or worse, hip-hop’s biggest antihero. Flawed, but always fighting—often for the people.

Neither Kodak Black nor NBA YoungBoy have been as socially engaged as Pac, but they both speak for young Black men in a similar manner. Both heavily explore grief, despondency, and a feeling of servitude to the streets in their music. Both artists are commercial tentpoles in a too-large field of young acts seemingly doomed to believing in the determinism of institutional racism, where death or jail are the only conclusions so many oppressed youth can see. Contrary to some people’s confusion surrounding their misdeeds, there’s little surprise that they can’t seem to get right. When you feel like your life is already fated, what’s the point of working on yourself?

These artists are even more frequently covered than Tupac because of the speed and scrutiny of today’s news cycle. While people heard about Tupac on a headline-to-headline basis, we follow today’s acts on a day-to-day basis via social media and gossip blogs. We see their daily posts and live streams. Even their friends and romantic interests have a modicum of notoriety just for their proximity to them. These dynamics lead their fans to stoke a deep parasocial relationship “with” them, where onlookers feel like they engage them on an almost personal level, want the best for them, and hence are more prone to rationalize their misdeeds.

Kodak Black is one of today’s primary beneficiaries of that dynamic. His Florida twang and charismatic mic presence are at the core of party-starting tracks like “No Flockin” and “ZEZE,” but his introspective music is what sets him apart from most artists in his lane. His 2018 Dying to Live album, the last project he released while free, was critically acclaimed. Drake called it one of his “favorite albums of the past five years,” commending him for bars where he “raps about his friends and purpose” and writes from a “God’s-eye-level view of his own life” on confessional tracks like “Close to the Grave,” “Malcom X.X.X.,” and “Testimony,” where he rhymed, “Everything I went through made me who I am ‘cause he be testin’ me.”

NBA Youngboy similarly relates to those trials. At the start of his “Lonely Child” track, the embattled Baton Rouge rapper strikes back at those who “talk about me like I ain’t human, but we all is,” before crooning, “I’m just a lonely child / Who wants someone to help him out.” It’s a harrowing song that speaks for youth who feel misunderstood and thrown away by society.

He recently doubled down on that sentiment, lamenting on livestream that “I’m lost...I ain’t lyin’ to you. Need some help, for real...I can’t find shit that’s genuine.” He smiled, downplaying the seriousness of his dismay, but anyone familiar with his music (or his legal woes) knows he wasn’t joking.

He was recently arrested by the FBI on weapons charges related to a September incident in Baton Rouge. Given that he’s already on a suspended 10-year sentence that depended on good behavior, his situation looks bleak. It’s easy to see how society failed YoungBoy and have empathy for that aspect of his experience. But the reality is that “hurt people hurt people,” and few can purely sympathize with him based on the 2018 violence with his ex. He can only vanquish his pain with a process that starts with accountability for past pain caused. Hopefully it’s not too late for him to make the most of his life.

Kodak and YoungBoy’s personal songs present the kind of existential, relatable narrative that hooks fans—and fellow Black males—who feel the same way about their own lives. But unpacking the specifics of those “tests” they refer to demonstrates why romanticizing their struggles is unhealthy. We tend to ignore that the artists who chronicle their proximity to gun violence can also find their trauma manifest in violence against women.

Along with his sexual assault case, Kodak has a history of disrespecting women. He rhymed “I’m already Black, I don’t need no Black bitch” in 2017. A Florida bartender accused him of “mushing” her in April 2017. He had controversial lyrics about wanting to have sex with rapper Young M.A in 2019. And just recently, he jokingly suggested that Megan Thee Stallion should “throw it back on em” because she used his “drive the boat” phrase. Antonia Farzan asked of him in the Miami New Times, “Is he the product of larger societal problems, having been raised on a steady diet of misogynistic rap lyrics?”

The problem with considering real people through a lens of antihero “complication” is that it dismisses the fallout of their actions and gives them the leeway to continue hurting people.

Cole expressed a similar idea when he defended pro-Kodak lyrics by noting, “I get it, there’s some people out there that do things that a person can’t fathom loving anybody that can do that. But nobody becomes that way overnight.”

That’s true. Society is ugly and creates people who do ugly things. And no one is the worst of what they’ve done. The prison industrial complex, which warehouses over 2 million people, preys on society believing otherwise. Criticizing someone who is so open about fighting trials created by racism can sometimes feel like siding with the oppressor, but on the other side of the coin is a proper respect for the people they hurt. When victims become mere apparatus that are rolled into a sympathetic narrative, it serves nobody. The accused feel no accountability, and survivors feel unheard.

It’s healthy for people to recognize our ugliness; it’s unhealthy to stay mired in it, or to stand silent, watching someone do that. It’s true that our flawed society molds flawed people who elicit thought-provoking conversations about morality and societal conditioning, but those people aren’t to be championed because they’re talking points. The prevalence of abuse being mere context is par for the purview of a patriarchal world, where the majority of society is male-serving, and the mistreatment of women isn’t a tragedy, but a development arc.

Vince Gilligan once explained of Breaking Bad, “In every individual episode, Walter’s a little further along the continuum between good guy and bad guy. And because our audience is not monolithic, and every viewer has his or her own interpretation, I like to picture viewers losing sympathy for Walt.’”

With fictional antiheroes, victims become mere vessels of the plot that are used to express what the writers want to say about the protagonist and the society that made them. The Sopranos was never going to end after the first episode because Tony Soprano was arrested for killing someone. The “right thing” never happens because it’s a TV program meant to keep showing us the bad things to ultimately drive home a point.

The problem with considering real people through a lens of antihero “complication” is that it dismisses the fallout of their actions and gives them the leeway to continue hurting people. So few of these artists ever admit to their abuses or publicly apologize to their victims, which makes it impossible to “move on” from.

Cinema is better for morally ambiguous protagonists, but these shows were created in part to demonstrate that society suffers from moral ambivalence. Even the complicated people we love ultimately meet unfortunate fates if they don’t try to correct themselves. Many of us gloss over this reality while lionizing our favorite antiheroes.

The best thing for the rap community is to stop dismissing the abuse of so many young artists and challenge them to be their best selves, whatever that looks like. More artists should challenge Kodak in the same way they did when he made comments about Lauren London. Ultimately, what he’s accused of in South Carolina is more consequential than mere comments. But ultimately, that doesn’t seem likely. The rap world, like the society it reflects, is deeply patriarchal. These men are only seen as antiheroes because of a society that doesn’t give women the same consideration as men. That’s villainous.