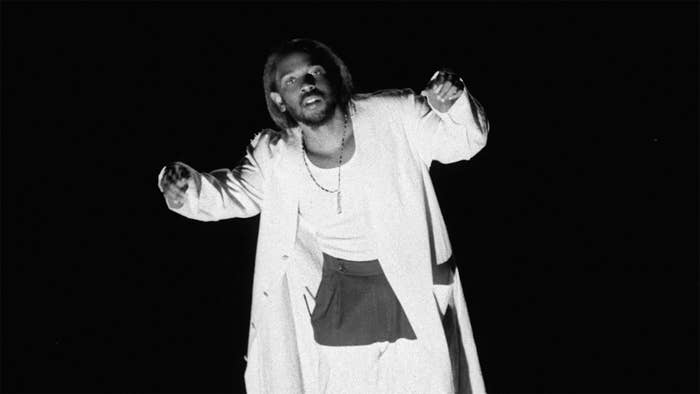

After five long years, Kendrick Lamar returned to deliver Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers, a double album that depicts himself and those in his world assuming facades as “big steppers” to mask the inner trauma that they’re tap-dancing around.

“We Cry Together” captures a lay-it-all-out argument between Kendrick Lamar and Taylour Paige that devolves into a gender war and abruptly pivots into sex. Their happy ending may feel good, but it shows them sidestepping the issues they just leveled at each other. The 2022 successor to RZA’s “Domestic Violence” veers from Alchemist’s moody piano loop into tap dancing, before Kendrick’s fiancée Whitney Alford tells him, “Stop tap dancing around the conversation.” The moral of the track is lobbed at our head like an errant tennis ball after Kendrick and Taylour’s incendiary back and forth.

On “Father Time,” which starts with Whitney urging Kendrick to get therapy, he raps about how his “daddy issues” imbued him with a “foolish pride” that he conflated with masculinity. On “Mother I Sober,” he asserts, “Every other rapper sexually abused/ I see ‘em daily buryin’ they pain in chains and tattoos.” And the crux of “Mother I Sober” explores how the shame of his mother thinking he was abused as a five-year-old eventually led to “seven years of tour, chasin’ manhood,” which turned into family-threatening infidelity that he divulges numerous times, including on “Worldwide Steppers.” Throughout the 18-track album, Kendrick analyzes his own life experiences, asking society if we champion toxic behaviors because deep down, we feel inadequate.

The album’s thesis statement has drawn praise from many, including Quality Control CEO Pee, who tweeted, “Kendrick album makes you really look in the mirror and question yourself.” But other junctures of Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers have critics questioning Kendrick about the presence of accused rapist Kodak Black, his crusade against so-called “cancel culture,” and misgendering on “Auntie Diaries,” a song about trans acceptance. Kendrick falters when he steps out of his world and offers larger social commentary on Mr. Morale, representing the faults of an otherwise phenomenal album. As he rhymes on “Crown,” however, he’s accepted that he “can’t please everybody,” and for better or worse, he’s not interested in trying. As he says to open “Savior,” “Kendrick made you think about it, but he is not your savior.”

As always, Kendrick is a masterful vocalist, unfurling myriad flows and phrases with a quirkiness that glues them to your psyche, like his unconventional enunciation of “yeah baby” on “Purple Hearts” and “brother” on “Rich Spirit.” On “Worldwide Steppers” he veers through reflections on infidelity and dalliance with white women through a monotone, rapid-fire delivery that sounds like he’s warping through a binary field, emphasizing the headrush he’s feeling as qualms and memories whirl through his mind. On songs like “Father Time,” he rhymes with trademark ferocity, while on “Mother I Sober,” he traverses from a gentle whisper into empowered theatrics, vocally symbolizing the song’s ascent from despair into awakening. Yet again, Kendrick’s verses are compelling from an audial standpoint.

View this video on YouTube

Thematically, the album depicts Kendrick’s rocky road through trauma, breakthrough, and spiritual consolation, presented in a scrapbook format. The double album is split in half: Side A is Mr. Morale, and the last nine songs are Side B, The Big Steppers. While the project is devoid of overt Billboard plays like “Humble,” “i,” or “Love,” Side A shows Kendrick relatively more intent on mass appeal than he is on Side B, with the uptempo production on “N95,” two-step ready drums on the breezy “Die Hard” with Blxst, and warm synths on the ’90s R&B-inspired “Purple Hearts” with Summer Walker and Ghostface Killah. He employs his “Swimming Pools” approach on the first half of the double-album, hooking listeners into his explorations of existential tumult through the metaphorical lens of vices. On “Father Time” he rhymes about how he and his father’s feelings are “bottled up no chaser,” on “Purple Hearts” he’s “mud-walking” through life as if he was on syrup, and he begins “Die Hard” by “[popping] the pain away.” Most of the tracks on Side B, meanwhile, are lush, layered soundscapes crafted with more experimental choices that allow Kendrick to sprawl out his deeply personal bars over shifting production. Side A will sound great on car speakers, and Side B’s theatrical production is ripe to be played live during his upcoming world tour.

The album’s connective tissue is formed by symbolic tap-dancing from young dancers Freddie and Teddie, references to spiritual teacher Eckhart Tolle and his The Power of Now book, and words from Kendrick’s fiancée Whitney. Collectively, the songs form a portrait of Kendrick Lamar taking stock of his shit through enlightening therapy sessions. On album intro “United In Grief,” he rhymes, “I went and got me a therapist/ I can debate on my theories and sharing it,” framing the project as his sounding board.

Kendrick’s fiancéee Whitney urges him to seek therapy at the beginning of “Father Time,” before he delves into a story of “falling backwards, tryna keep balance” as a young man, deluded by his father’s tough love and repressed emotions. The song carries worthwhile takeaways for all young men who have been conditioned to view vulnerability as feminine instead of simply human. “What’s the difference when your heart is made of stone/ And your mind is made of gold, and your tongue is made of sword, but it may weaken your soul?” Kendrick asks, offering a piercing quandary for millions of people who feel inherently flawed as a result of a complicated upbringing.

“Worldwide Steppers,” laced with a brooding bass that harkens to scummy 36 Chambers production, opens with Kodak Black shouting out Eckhart Tolle, before Kendrick spits one of his best verses ever, spilling on his desire to protect his children, explaining how his “lust addiction” altered his relationship with his wife, and asking God to speak through him lyrically. And then, to underscore the chaos in his head, he pockmarks an image of mind-body-soul purity (“Sciatica nerve pinch, I don’t know how to feel/ Like the first time I fucked a white bitch”) by going on a diatribe about having sex with white women as a means of resistance against “the man’s” oppression.” On the surface, the second verse is a jarring trip to trope-ville, but that’s the point. In the context of the album, “Worldwide Steppers” is him looking back at his never-ending search for phallic relief (also notably shown on “We Cry Together”), which is a major theme of the project.

View this video on YouTube

Kendrick reflects society’s collective confliction throughout the album. Even if he’s in the woods fostering a divine connection, he’s still a work-in-progress. On “Count Me Out,” the opener of Side B, he admits, “I care too much, wanna share too much, in my head too much/ I shut down too, I ain’t there too much.” “Father Time” contains the hilarious admission that “when Kanye got back with Drake, I was slightly confuse / Guess I’m not mature as I think, got some healin’ to do.” And on “Die Hard” he tells his girl, “I hope I’m not too late to set my demons straight/ I know I made you wait, but how much can you take?”

At the start of “Mother I Sober,” he rhymes, “Where’s my faith? Told you I was Christian, but just not today.” The six-minute thriller is demarcated by two interconnected moments of truth: Kendrick is being honest to his mother that he wasn’t sexually abused, but lying to his fiancée about his sex addiction. He coalesces the answers by rhyming about how his mother’s doubts about him not being abused made him insecure and projected into a “lustful nature.” The third verse of “Mother I Sober” represents the climax of the entire project, as Kendrick rhymes about the devastation of familial abuse that spawned his misogyny and exhausting performance of masculinity. This is Kendrick at his best, delving internally, making connections, and delivering the kind of breakthrough that has made him one of hip-hop’s most indelible MCs—all while rapping with a captivating fervor. At the end of the song, Whitney congratulates him for breaking through generational trauma, and his baby makes an appearance. It would have been a perfect outro.

Right after he “frees” abusers and those with “hearts filled with hatred” on “Mother I Sober,” accused rapist Kodak Black opens “Mirror” by asserting “I choose me.” It’s impressive to hear Kendrick work through the ways trauma has informed his vices and flawed perceptions of masculinity, but Kodak’s multiple appearances add a confusing wrinkle to the album’s overall messaging.

As Kendrick boasts, “I choose me, I’m sorry,” it’s difficult not to think about Kodak pleading guilty to first-degree assault and battery in his sexual assault case with an 18-year-old woman, then tweet out a sunglasses emoji to flout his evasion of sex offender status. Kendrick, like J. Cole, Drake, and hoards of fans, love Kodak because he’s a talented 24-year-old from Florida who symbolizes young Black people the system preys on. But he’s also become a posterboy of hip-hop as a boy’s club that champions fellow men in spite of what they’ve been accused of doing to women. An album about men choosing violence and misogyny to mask their pain would have been a perfect moment for Kodak to dig deep, but his “Silent Hill” verse shows him mostly opting for braggadocio and tough talk. In the album’s “big steppers = scared tiptoer” equation, Kendrick let Kodak sidestep real reflection.

Kendrick comes across as unbothered by the fact that Kodak’s presence throughout the album will rankle listeners and former fans. On “Mirror,” he reflects, “Lately, I redirected my point of view/ You won’t grow waitin’ on me/ I can’t live in the matrix, rather fall short of your graces.” The solemn “Crown” is structured like a weary folk record, with short verses surrounding the refrain that he “can’t please everybody,” which he repeats a whopping 51 times.

“Cancel culture” is Kendrick’s second-biggest opp on Mr. Morale, after his own demons. On “N95,” he questions, “What the fuck is cancel culture, dawg? Say what I want about you niggas, I’m like Oprah, dawg.” Then he proclaims, “The industry has killed the creators, I’ll be the first to say” on “Worldwide Steppers,” also suggesting that “cancel culture” has affected the artistry of his peers, rhyming, “Bite they tongues in rap lyrics/ Scared to be crucified about a song, but they won’t admit it.” Tellingly, “Savior” is the first moment where he explicitly opposes himself from the tiptoers:

Two times center codefendant judging my life

Back pedaler, what they say? You do the cha-cha

I’ma stand on it, 6’5” from 5’5”

Fun fact, I ain’t taking shit back

Like it when they pro-Black, but I’m more Kodak Black

Kendrick tears through the experimental production on “Savior,” chastising listeners who look for entertainers as guides. “Cole made you feel empowered, but he is not your savior/ Future said, ‘Get a money counter,’ but he is not your savior,” he raps in the song’s intro. Could Mr. Morale be a snarky nickname that he gave himself to reference the weight that he feels people put on him to be their moral compass? At the end of the first verse, he questions, “meditating in silence made you wanna tell on me?” as a retort to consumers who criticized his 2020 silence during a worldwide anti-police uprising. The line could have been sharper than the imprecise “tell on me,” which doesn’t accurately represent the dynamic (who were we” telling on” him to?) but his sentiment still radiates. He’s asking why he was put on front street and expected to speak out while he was processing the tragedy just like us. The knee-jerk reaction is for fans to mention him being lauded as the voice of a generation, but he’s declining that responsibility throughout the album. On “Savior,” and the rest of the album, he’s proposing that perhaps he’s not the voice of a generation, and he simply made songs that a generation relates to. What about him poetically encapsulating our collective despair suggests that he has the answer to it?

Elsewhere on “Savior,” Kendrick incisively explores how putting too much faith in one man is tenuous, as he notes, “Seen a Christian say the vaccine mark of the beast/ Then he caught COVID and prayed to Pfizer for relief,” and rhymes, “I rubbed elbows with people that was for the people/ They all greedy, I don’t care for no public speaking.” While the “Tupac is dead, think for yourself” line is a clunker, “Savior” is nonetheless a worthwhile critique on our expectations of celebrities.

Curiously, Kendrick is reticent to lead the masses against the powers that be, but adamantly places himself against us when deriding “cancel culture” on the album. “The industry has killed the creators, I’ll be the first to say,” he volunteers on “Worldwide Steppers.” But his assertions ring hollow, as few men in entertainment have had their career “killed” by questionable statements or behavior. In 2015, Kendrick upset many by opining, “When we don’t have respect for ourselves, how do we expect them to respect us?” following Mike Brown’s police killing. But two years later, DAMN broke sales records. And months after that, he leveraged his power to get XXXTentacion placed back on Spotify playlists after they removed him for allegedly abusing his ex-girlfriend. Polarizing artists like Kodak, Chris Brown, DaBaby, Tory Lanez and more still have careers as long as men like him are around to overlook a peer’s misdeeds. And while he may think he’s protecting “free speech,” that perspective always overlooks the victims and accusers of these men.

No artist in America is banned from expressing what they want in their music. But more artists simply have to accept that if their content riles marginalized groups, they will speak up, because they have a bigger voice now. Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers’ anti-”cancel culture” moments hint that it may be time to retire the notion of “conscious rap” once and for all. The phrase made sense when being progressive and conscious of hip-hop listeners’ needs was as simple as highlighting the toll of gun violence, systemic oppression, and extolling the benefits of spirituality. But time has exposed “conscious” rap’s patriarchal roots, and too few rappers are truly conscious of how to reach a consumer base that’s more diverse, and vocal, than ever.

View this video on YouTube

“Auntie Diaries” is a noble record, bogged down by criticism derived from him misgendering and deadnaming his trans uncle and cousin while telling their stories. Deadnaming means referring to a transgender or non-binary person by a name they used prior to transitioning. And while some in the trans community have vied to overlook his miscues, figuratively meeting Kendrick where he’s at while he’s meeting listeners where they’re at, other people in the community feel like the misexecution makes it “a song made for straight people to congratulate themselves for having the ‘conversation.’” The song’s overall message of acceptance and rejection of hatefulness is needed and should be built on by other rappers, but when Kendrick centers himself in their narrative to reflect on using the F-word, twice chanting the word, the song becomes unlistenable for many of the very people he’s trying to advocate for.

Mr. Morale & The Big Steppers shows Kendrick at his most curious and sonically ambitious. The project affirms Tyler, the Creator’s rave review of “Family Ties” as an exhibition of “someone at that level still gunning.” He’s trying new shit. He’s trying new voices. He’s still learning. You can tell he was “off his phone for a few months.” As if he’s bored with merely tearing down the verse-hook-verse format, he harkens back to the experimentation of untitled, unmastered by presenting a range of song structures. He threw a lot against the canvas, and unfortunately it didn’t all stick, but that’s the nature of taking chances in your work, and openly scrutinizing junctures of life he claimed no mastery of. Even as a top-tier lyricist, and a wildly imaginative creator, he’s still not as sharp as he could be at examining the systemic elements that cause the traumatic pain he brilliantly dissects. But then, as he compellingly demonstrates, that’s the point of the whole album.

![Thematically, the album depicts Kendrick’s rocky road through trauma, breakthrough, and spiritual consolation, presented in a scrapbook format. The double album is split in half: Side A is Mr. Morale, and the last nine songs are Side B, The Big Steppers. While the project is devoid of overt Billboard plays like “Humble,” “i,” or “Love,” Side A shows Kendrick relatively more intent on mass appeal than he is on Side B, with the uptempo production on “N95,” two-step ready drums on the breezy “Die Hard” with Blxst, and warm synths on the ’90s R&B-inspired “Purple Hearts” with Summer Walker and Ghostface Killah. He employs his “Swimming Pools” approach on the first half of the double-album, hooking listeners into his explorations of existential tumult through the metaphorical lens of vices. On “Father Time” he rhymes about how he and his father’s feelings are “bottled up no chaser,” on “Purple Hearts” he’s “mud-walking” through life as if he was on syrup, and he begins “Die Hard” by “[popping] the pain away.” Most of the tracks on Side B, meanwhile, are lush, layered soundscapes crafted with more experimental choices that allow Kendrick to sprawl out his deeply personal bars over shifting production. Side A will sound great on car speakers, and Side B’s theatrical production is ripe to be played live during his upcoming world tour.

The album’s connective tissue is formed by symbolic tap-dancing from young dancers Freddie and Teddie, references to spiritual teacher Eckhart Tolle and his The Power of Now book, and words from Kendrick’s fiancée Whitney. Collectively, the songs form a portrait of Kendrick Lamar taking stock of his shit through enlightening therapy sessions. On album intro “United In Grief,” he rhymes, “I went and got me a therapist/ I can debate on my theories and sharing it,” framing the project as his sounding board.

Kendrick’s fiancéee Whitney urges him to seek therapy at the beginning of “Father Time,” before he delves into a story of “falling backwards, tryna keep balance” as a young man, deluded by his father’s tough love and repressed emotions. The song carries worthwhile takeaways for all young men who have been conditioned to view vulnerability as feminine instead of simply human. “What’s the difference when your heart is made of stone/ And your mind is made of gold, and your tongue is made of sword, but it may weaken your soul?” Kendrick asks, offering a piercing quandary for millions of people who feel inherently flawed as a result of a complicated upbringing.

“Worldwide Steppers,” laced with a brooding bass that harkens to scummy 36 Chambers production, opens with Kodak Black shouting out Eckhart Tolle, before Kendrick spits one of his best verses ever, spilling on his desire to protect his children, explaining how his “lust addiction” altered his relationship with his wife, and asking God to speak through him lyrically. And then, to underscore the chaos in his head, he pockmarks an image of mind-body-soul purity (“Sciatica nerve pinch, I don’t know how to feel/ Like the first time I fucked a white bitch”) by going on a diatribe about having sex with white women as a means of resistance against “the man’s” oppression.” On the surface, the second verse is a jarring trip to trope-ville, but that’s the point. In the context of the album, “Worldwide Steppers” is him looking back at his never-ending search for phallic relief (also notably shown on “We Cry Together”), which is a major theme of the project.](https://img.youtube.com/vi/zI383uEwA6Q/mqdefault.jpg)