Lil Baby fiddles with dice the way others fold up their napkin or twirl their hair. Within a minute of entering the bunker-like studios belonging to Atlanta label Quality Control, where fellow signees like Migos and Lil Yachty also record, Baby spots a red die and instinctively shoots it across the countertop. He throws it without looking while carrying on a full conversation about staying motivated.

Quality Control’s studios is, first and foremost, a place of business. But according to signs posted around the building, the “house”—Quality Control co-founders Kevin “Coach K” Lee and Pierre “Pee” Thomas—gets 30 percent of all gambling winnings. Management may as well have called it the Lil Baby rule. “I’ve had so many dice in here from over time,” the rapper says. “I’ve had some crazy games in here—this room, that room, any room in here—with 12, 15, 20 people.”

Before last summer turned to fall, and his breakout hit “My Dawg” consistently filtered out of car windows in his native Atlanta neighborhood of West End, Baby wasn’t even rapping. He was too busy shooting craps as a full-time hobby to give any serious thought to anything outside of that. So six years ago when Coach K, who was introduced to Baby through Pee, told the teen that he should start rapping because he “got the swag for it,” he completely brushed off the idea.

Baby couldn’t see what they saw back then. He never could have imagined landing at the same label as Coach’s then-new clients Migos, or opening for PnB Rock this past spring. He couldn’t have predicted that, when Kevin Gates became a freed man in January, that the Baton Rouge rap stalwart would recite Baby’s own lyrics back to him over the phone (“This n***a knew the words to my songs,” Baby wrote on Instagram). He didn’t know how to bet on himself; not as he does now at 23.

“Growing up you ain’t even learn about the odds,” Baby says. “You just know it’s a hustle: Sometimes you win, sometimes you lose, you just try. But since I’ve been rapping, I’ve been so busy that I haven’t even been gambling that much. I used to always be in Atlanta, chilling. I didn’t really have as much to do. So I would gamble as a hobby. Now I’d rather go into the studio and try to make me a hit.”

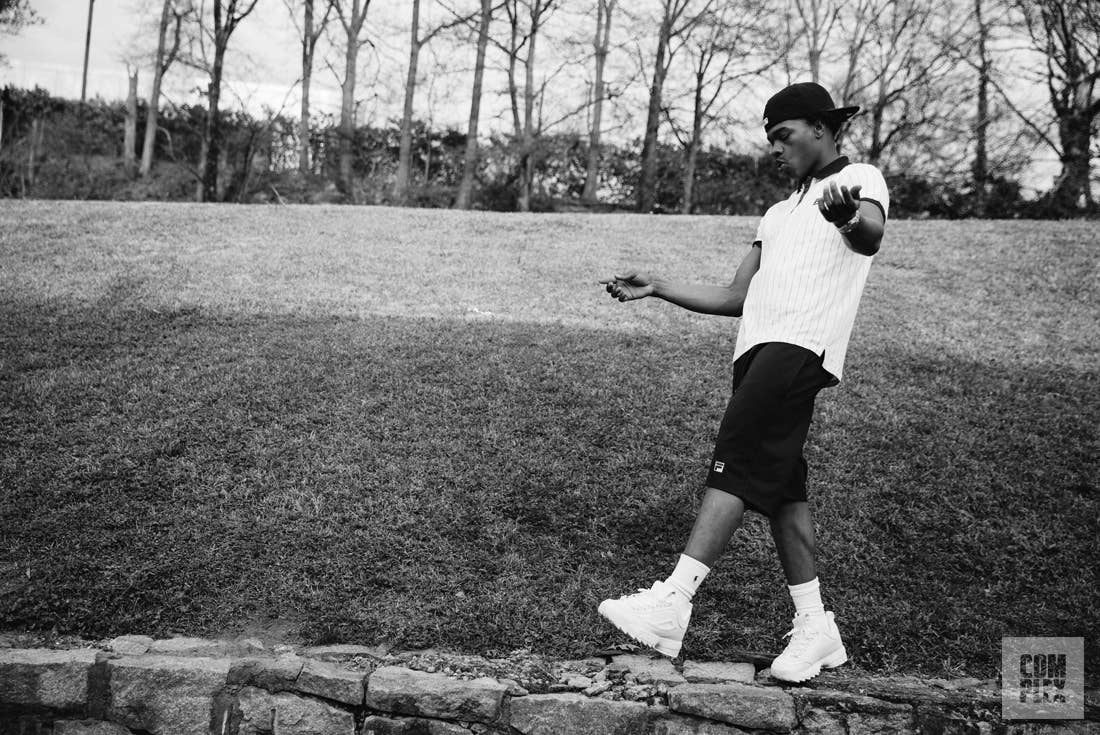

Baby’s the kind of guy who stands out in a crowd. Today he’s wearing all FILA, complete with a cap and chunky Rays—the “dad” sneaker that has made actual dads wonder how they’ve become hip again. The sneaker collection he started at 16 now fills up six closets in Atlanta: two at one house, two at his other residence, and two at his mom’s place. Shoes are a relatively harmless vice, but when he was younger, Baby admittedly got caught up in “teenage boy type of stuff,” like gambling, fighting, and skipping class until he dropped out altogether despite his good grades. He also sold drugs until he got busted and was sentenced to five years. It wasn’t until Baby was released in 2016, after only serving two years, that he finally acted on Coach’s advice about pursuing a career in music. Never mind that his only prior experience at the studio was watching friends like Young Thug enter the booth.

Even before Baby shifted his focus, he already had the attention of Ferrari Simmons, a popular evening radio personality on Atlanta’s Streetz 94.5. Migos might have agreed to be featured on Katy Perry’s “Bon Appetit” and Lil Yachty appeared opposite Carly Rae Jepsen in a Target commercial, but, at its core, Quality Control is still all about everlasting street appeal. That’s exactly what Simmons saw in Baby before he even dropped his first mixtape, Perfect Timing, a year ago. Fortunately for the rap rookie, that appeal translated to his music. While Migos and Yachty riff off trap rap conventions to an ostentatious pop art effect, Baby’s songs like “Survive Da Motion” are practically folk music of the most delicate kind. The slight Autotune isn’t nearly as perceptible as the weariness that forces his voice to creak.

“I would gamble as a hobby. Now I’d rather go into the studio and try to make me a hit.”

“Baby’s from [Southwest Atlanta], and those around there know his situation,” Simmons says. “He’s a real tough guy, and he makes quality music. These days people aren’t who they say they are. But if they check out, especially in Atlanta… Atlanta supports its own more than any other city, to be honest.”

Simmons saw that happen firsthand, when “My Dawg,” off Baby’s DJ Drama-hosted second mixtape Harder Than Hard, took off in his hometown before officially being released in July.

“I’m at seven nightclubs, sometimes 12, in a seven-day span,” the radio jock says. “[Baby’s] song was basically at every club that I was at. Even if I wasn’t working, you would see it get played. It was prom season when I first met him. People were coming up to the DJ booth when I was crashing high school proms and requesting Baby’s music. That’s how I knew he was getting really, really popular.”

Once prom season ended, the “My Dawg” video was viewed 41 million times on WorldStarHipHop's YouTube page. The single also marked Baby’s chart debut, making him one of four “Lil” rappers to make a splash in recent months, along with Pump, Skies, and Xans.

“Everything is crazy, coming from never being in the limelight to being [snaps] well-known,” Baby says. “Especially in Atlanta, where some of the craziest stuff has happened. Like people coming up to me like, ‘Nobody ever told you that you look like Lil Baby?’ But I’ll be like, nah. Or like, somebody told me that. I’ll never just say, it’s me. But I actually see people walk up on me with their phone on Google, like, ‘Look!’ Whether I’m at the gas station or I be at the store, I be there by myself. I be regular.”

From the moment Baby stepped inside Quality Control Studios for this interview, he has refused to sit down. He’s too excited to share his story and continues to pace around the room. The longer he talks about how fans wait for him at the airport, spot him when he pumps gas, or call his cell after somehow tracking down his number, the more animated he gets. At this point, he might as well be on stage given how much energy he’s exerting.

Baby launched his rap career with the lofty goal of releasing four mixtapes in 2017: Perfect Timing, Harder Than Hard, Too Hard, and a collaborative project with fellow ATL rapper Marlo, 2 the Hard Way. He wants to release four more in 2018, starting with the recently released Harder Than Ever. Eight full-lengths in two years is a lot to ask from any given artist. But that pace has also helped Baby build career momentum almost as quickly as he learned to rap. Harder Than Ever’s stacked guest list, from Young Thug and Offset to Lil Uzi Vert and Nashville rapper Starlito (“one of my favorite rappers”), is a testament to his expanding inner circle as a result.

New single “Yes Indeed,” featuring Drake, was a last-minute addition: “When it was time for [Harder Than Ever] to get turned in, Coach K called and told me that that record was going on my album,” Baby reveals. “Up until maybe four or five days before the deadline, I didn’t know that was going on my album.” By now, Baby knows better than to question his label bosses’ judgment. How could he, when Drake actually shouts him out on the song? Baby’s verse is the young artist responding to this feat in real time (“Me and Drake ’bout to drop, man, this shit gon’ go crazy”). “I was amazed,” he says, still in awe.

This steady stream of releases is only one reason why Baby has drawn attention from Atlanta’s already-crowded rap landscape. As Coach K predicted when they first met six years ago, Baby can draw listeners in with memories of selling nicks and dimes at West End Mall. He alternates between confessing that Percocets have been his crutch to warbling about how he doesn’t do drugs anymore, without there being a clear timeline. (For the record, Baby says that he has indeed stopped: “I feel like if something ain’t too good for me, I’ll start to shake it.”)

“At first I didn’t even want to talk about my past at all... I’m not fully comfortable opening up, but I’ll do what I have to do, more than when I started.”

In other instances, Baby can be more reflective. Take the first verse of “Best of Me,” off Too Hard, where he’s so scared that a kid might have died in a shootout he was involved in, he doesn’t even think about how his own reputation might be affected. “I remember on the way back, everybody in the car quiet,” he raps. “I just knowing everybody thinkin’ we just pulled a homicide, homicide / See me on the news at the spot, tryna see who they say got shot.”

“Best of Me” contains the sort of “authenticity” that we crave—no, require—from rap of this subgenre. But it is also haunting, and can hurt to hear. Baby says that Harder Than Ever is equal parts weighty and triumphant, with songs like “Yes Indeed” and “Southside.” Yet truth be told, he would much rather move on from his troubled past altogether.

“At first I didn’t even want to talk about my past at all,” Baby says. “Even now, I don’t really do too much talking. But when I do, I know how to interact with people, you know what I'm saying? It’s like a lot of stuff, where I have to tie up my shoes and run with it. I’ve had a couple of people take me to the side and tell me how to go around certain questions. I’ll let them know that I’d rather not talk about that. All I’m doing is processing.”

“I’m not fully comfortable opening up, but I’ll do what I have to do, more than when I started,” adds Baby, as he wanders to the other side of the room.

Baby’s manager Rashad can vouch for that. He’d much rather do that than even detail his own résumé, which includes time with Gorilla Zoe and Future. Rashad audibly cringes when asked to disclose his last name, which he never does. (He values being “super low key,” to where he hasn’t been on social media in seven years.) But ask him about how Baby has embraced the value of hard work, and Rashad becomes an open book.

“Oh, it’s been great,” Rashad says over the phone. “Baby’s booked up two months in advance. Soon as the calendar opens, in four or five days the next month is booked out. Promoters love him because he's real personable, he always gives thanks, and he gives them a show.” (For the record, Baby is just as polite in interviews, ending almost every response with an earnest, “Yes, ma’am.”)

“He enjoys performing and seeing his fanbase grow and grow and grow,” Rashad adds. “I’m so happy about that because it allows him to expand his brand. Being an entrepreneur is good when you’re around somebody like Pee and Coach. You get to see the blueprint, and they’re not shy about giving game. ‘This studio is here for you to work. It’s an office space for you to handle business.’”

Baby has taken them up on that invitation countless times over. When he started rapping, his workday at Quality Control’s studios started at 1am, though he has since become a morning person, with sessions starting as early as 9am. Like on most days, his “Freestyle” video, with 69 million views and counting, ends at QC. Baby, wearing sunglasses inside, wanders into a room to recite the song’s last few bars as if pitching them at some board meeting. “Ain’t even in their business, they ain’t want to fuck with me / Now they see a ni**a dripping, now they want to fuck with me,” he taunts. “They can’t even get towards me, hardly in the city / They just know I’m getting bigger, they just know a ni**a busy / I’ve been running all them digits, yeah.” The whole time, Pee had been looking up from his plate of food at the countertop, smiling: “That how you feel?”

As “Freestyle” makes clear, Baby would much rather revel in his good fortune, how he is free now, than how he was imprisoned before. He has created a regimen out of creating music, where peers like Marlo sometimes act as his accountability (“Let’s go to the studio”). And now with the positive reinforcement he has seen over the past year, from Atlanta and the college kids who flood his shows, Baby has decided that he would rather not leave anything up to chance.

“I don’t know how this game goes on a further level,” he says. “I can’t even envision the future, versus going to college for four years: ‘If I pass my test…’ The rap game is kinda crazy, so I go with the flow but make sure that I cover my bases and do whatever to make sure I’m good no matter what. Yes, ma’am.”