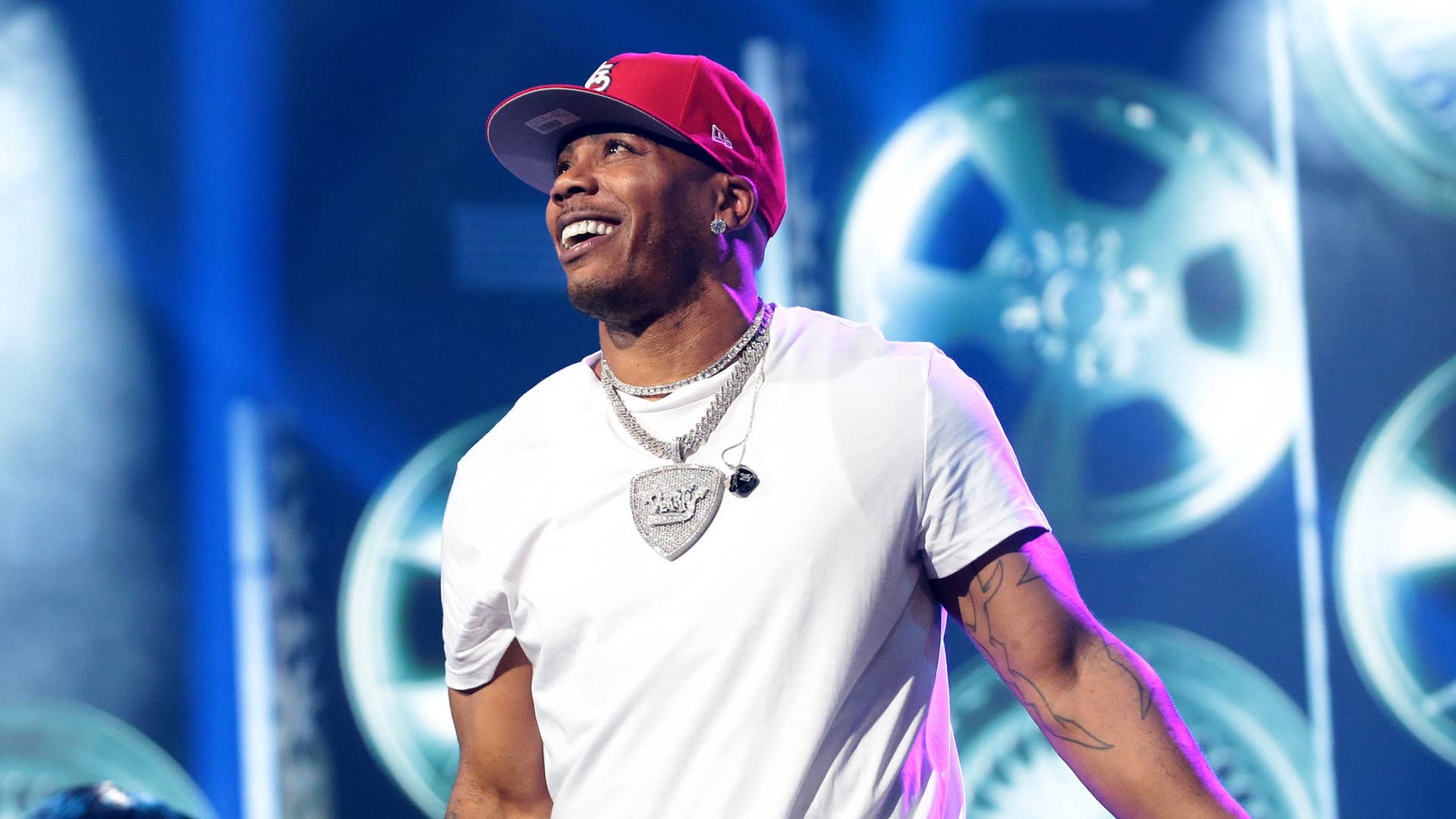

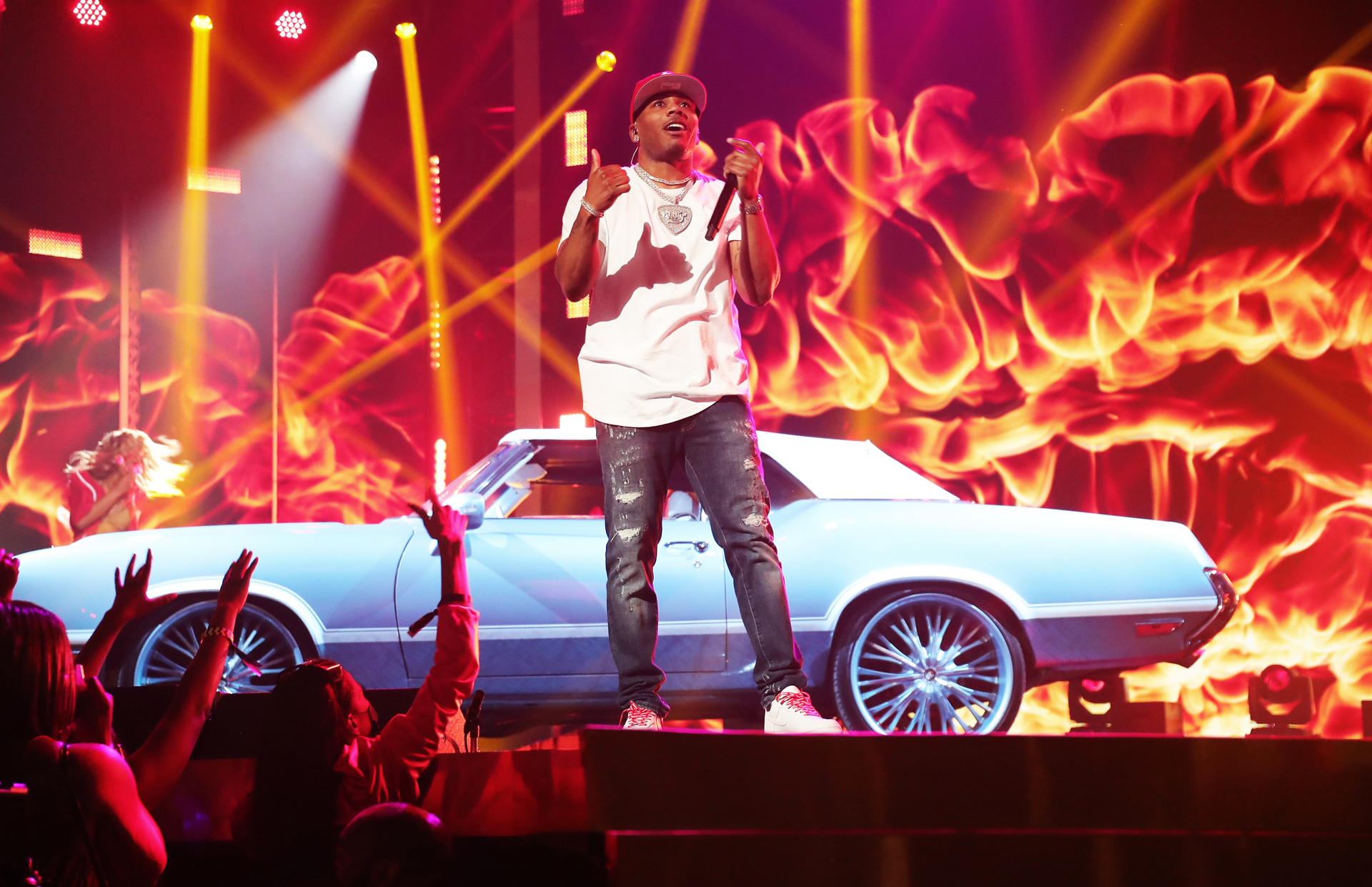

Image via Getty/Leon Bennett/2021 BET Hip Hop Awards

Nelly is a bonafide hip-hop legend, and BET has recognized that reality. On Sunday, the St. Louis rapper was honored with BET’S I Am Hip Hop award at their annual Hip Hop Awards ceremony, which will be aired on the network tonight at 9:00 p.m. ET.

Since breaking out in 1999 with the hit “Country Grammar,” Nelly has sold 21 million albums and been a part of 14 Billboard Hot 100 top 10s. But understanding his legacy isn’t just about recognizing the accolades, it’s acknowledging how he accrued them: by helping shift the sound of mainstream hip-hop.

As he points out, many of his singles are centered around feel-good, earworm melodies, but they each have their own distinct energies. ”I tried to set myself up for not being put in a box,” he tells Complex. “Well, how do you do that? First of all, nothing can sound alike in what you’re doing.” From the Chuck Brown-funk of “Hot In Herre” to the country vibes of “Ride Wit Me” and the ambitious “Over and Over” with Tim McGraw, many of his most notable singles have their own particular flair.

We caught up with Nelly about his 20+ year music career, including how his early festival experience inspired his ambition, his sonic influences, and his new album. The interview, lightly edited for clarity, is below.

You’re being honored with the I Am Hip-Hop award. How does it feel to be recognized by BET for your contribution to the game?

It’s definitely a blessing anytime you’re being honored for anything that has to do with art. That means that’s your creativity, that’s your vision. When somebody steps out there and says they feel like what you’ve done has made an impact in whatever it is that you’re doing, you’re thankful for that. It’s great.

How do you feel about your impact on the game, as far as infusing more harmony as a vocalist?

When you look at where music is now, it’s almost at a place where, if you don’t have some type of melody, it’s almost like it’s not going to work. Even if we look at some of the people who we call today’s lyricists, they have very strong melodies. Kendrick Lamar has great melodies. J. Cole has great melody when he’s rapping.

Back when I was doing it, I was singing my own hooks and rapping my own verses and there weren’t a lot of people doing that. My influences, CeeLo Green, Bone Thugs, Arrested Development, were huge, too. Even if you look at somebody who a lot of people wouldn’t even think about putting in this category—but when you go back and you listen to it, you’re like, “Damn, right”—is DMX. He had crazy melody. Crazy.

It’s almost like you can’t be in music today without that. And I feel like for one minute, the whole radio sounded like Nelly. But what happens is, when you are a great influence, people are inspired by you. It’s the same way as I was inspired by those before me. I was just able to take it to another level and show that you can do it in the same vein as what everybody else is doing, and you can [do] your own thing right next to them.

You haven’t been afraid to bend genres and explore new styles. Can you talk about rappers embracing the freedom to explore whatever musical influences they desire, without feeling any stigma about it?

I think that was my goal when I came into the game, but it was to set myself up for today, because that’s just how I saw life in general. I moved around a lot. I went to like eight different schools. I was asked to leave a couple of them, but a lot of that was just because of my upbringing, because I’m staying with my father, and my father couldn’t afford to keep me. I went with my mother, and my mother had to make sure she got her stuff together. So I was living with family members and friends of family. And when you move around a lot, you’re always the new kid. I was always reinventing myself.

That’s why I think I was built for this business. I can pick up and keep moving. I’m built to travel. I’ve been traveling my whole life. You can’t spend the first 12, 15, 16 years of your life bouncing around, and then all of a sudden you adapt and that’s how you see the world. And then you think what helps you deal with that is just going to go away. No, that’s the way you deal with things. That’s the way you’re used to moving. So I think that this business was meant for me to be in. I just hope people find that versatility is the key. That’s what I’ve always found.

You look at anybody who’s got 20-plus years in music, and it’s because they understood evolution. They understand versatility. I’m not saying that they’re changing who they are. They’re just figuring out how they fit in the now with what’s going on, as they should. That’s like anything. It’s like playing basketball. Like, you’re going to have to figure out how the game has changed. You have to figure out how your game fits into that game, or you could sit there and complain and watch it pass you by.

You’ve said that part of your impetus to explore country music came when you were being invited to a lot of festivals with country acts as an up-and-coming artist. What were you thinking when you were first booked for those festivals?

We were just happy to be here, like, “Did the check clear?” We got our money, and we were hopping on stage. We come from the Lou,’ man. We’re from the Midwest. We’re from a place, when you talk about Missouri, that wasn’t Union or Confederate, but we still had slaves. We’re not even in what’s going on with the war, but we got slaves. I think we’re like the only Midwest state to have slaves, you know?

So I just look at it differently. I know I got something, I just don’t know what it is. When I’m doing a show, but I have a major country act as a headliner, he’s the headliner. I’m taking my same show, flying the next day, and I got one of the biggest rappers in the world [as] the headliner. It’s the same show, bro. I ain’t changed nothing. I got the same songs, and damn near the same outfit on. It’s just a new white T-shirt, some Air Force Ones, and some size 42 jeans with a belt pulled tight. I’m hopping on the same stage, I’m doing the same damn show, using the same songs. But after about a year or so, you’re kind of looking at it like, “Yo, everybody ain’t doing this.”

We just thought it was the norm because we ain’t never did this before. We don’t know everybody else ain’t getting it like this. But once we found that out, then it was like, “Well, holy damn,” I’m a hustler. Once I see an opportunity, I’m going to pay attention to it, to a certain degree. Now, I may not capitalize on it right away, but I’m damn sure understanding that I have something that somebody else don’t have. And I need to understand that it’s a blessing. It either can be a detriment or it could be a benefit. And I chose to use it as a benefit.

In 2004, you actually collaborated with Tim McGraw on “Over and Over,” which is a landmark cross-genre collaboration. What made you take that chance? Did you ever feel any reticence about it?

Did I feel reticent about it? From other people, yes. From my label. But once I understood what I had, it’s like, “Yo, how am I going to use it as a benefit?” Everything had led up to that point. It’s like, “OK, I’m aware of it, but now how am I going to use it?” I tried to set myself up to not be put in a box. Well, how do you do that? First of all, nothing can sound alike in what you’re doing. My first song was “Country Grammar.” It doesn’t sound like my second song, “E.I.” It don’t sound like my third song, “Ride Wit Me,” which don’t sound like my fourth song, “Batter Up.” That’s all four singles off of Country Grammar. Now, Country Grammar is what is packaged.

Let’s move to the next project. Nellyville. “Hot In Herre” don’t sound like shit off Country Grammar. “Dilemma” don’t sound like nothing I’ve ever did. So, as you can see, the goal is to keep doing what people would consider big records or great songs, but they don’t sound alike. Everything is a new sound. Everything is a new look.

Then you get to a place like “Over and Over Again.” You’ve got to understand, I’m coming off of Country Grammar. I’m coming off of Nellyville. These are great albums. These are big. Nelly’s at his peak. And now he says he wants to do something with a country star. The label is looking at you like, “What?” Like, “Oh, well God, he’s trying to kill his career. He’s trying to take himself out.” And it was like, no, I get it. I’m put here to do something. I’m here for this, for this reason right here. Because can’t nobody else is doing it. They can do it after I do it, but can’t nobody else do it. And that’s the point that I realized what was going on. And yeah, a lot of people didn’t see it the way that I saw it, but I understood that my fans had allowed me to get to this point. And I knew as long as I made the music good, they would accept it.

You just released your Heartland album in August. What was the production process like for the songs on that album? Did you have to reach outside of your general collaborator network to put it together?

I made like three different trips down to Nashville, and things just got better and better each time. When I was getting down there, I was working with all these great producers and songwriters.

I would go in and explain to them, “Listen, this is your opportunity. Whatever you’re thinking that’s been outside the box, that’s been trapped in your brain, this is the opportunity to do it. We’re going to let it out. Because whatever you feel you couldn’t get away with, working with the traditional country artist, we can do it. We can pull it off. I want you to think outside the box, don’t worry about it. I know how to bring us back in. I know how to make sure that we stay on brand and on what’s going on.”

So yeah, I did work with a lot of different producers that I didn’t work with on the other [music], but that’s only because I needed that heartbeat of country music, and that’s in Nashville.

In what regards did it get “better and better each time” you went down there?

In [terms of] people understanding what the project was. Once I got down there and we started doing a couple of songs, the word started spreading about how these songs were sounding. It spread like wildfire, and people really wanted to work with [me]. The best way to be remembered in life is to be first, and to come with something that’s new and that’s fresh.

It’s easy to get on it after the path has been set. It’s easy to say, “Oh, OK, this is how we should do it, and this is what we should do.” That’s because somebody showed you. People always remember the teacher as opposed to the best student in class. You could be the best student in class, but people are always going to remember the teacher, because the teacher taught the best student in class.

So, I saw myself as kind of teaching great students who were already winning at country music about what we were trying to do in creating something new and possibly a new genre of music. You just never know where it ends with a new genre of music, with hip-hop being the base. And that’s a testament to hip-hop.

Have you had any conversations with those producers about their plans to continue that fusion going forward?

Well, I think they’re always going to rock. If you are a producer, I don’t think you ever slow down working. It’s the same way I got turned on to country music. People don’t know I got turned onto country music through Lionel Richie, because my uncle was a huge Lionel Richie fan and he made me pay attention to all things Lionel Richie—not just him as an artist or the production that he was doing on R&B and pop, but everything he did. And I found out that this talented brother was writing country music. And I’m like, “Yo, what the hell? How is this happening?”

Great lyrics transcend. When you’re telling a story, they transcend. The music can change here and there. You can listen to “Lady” on an R&B station, or you can listen to it on a country station, from the Kenny Rogers version to Lionel Richie’s version. “I Will Always Love You,” from Dolly Parton’s version to Whitney Houston’s version, that’s the same lyrics. It’s the same words, but their production is different. So, henceforth, you can listen to one on R&B and you can listen to the other on country.

There’s a new crop of St. Louis rappers. How often have you been in correspondence with them and given them advice?

I mean, some. I can’t communicate with all of them. Nobody can communicate with everybody in this city. But sometimes, when you’re from cities like St. Louis, you’re supposed to be Superman. Everything you do is supposed to be coordinated with everybody. You’re supposed to know everybody, and you’re supposed to be willing to help everybody. A lot of them pass through Derrty, pass through our studio. A lot of them come up working with us, using the studio. So I communicate with a lot of them. I mean, there’s a lot of young talent that I don’t have a relationship with, too.

I wish nothing but the best to the young brothers that’s doing it on their own. And I’m not saying that I won’t work with them in the future. I just haven’t worked with them yet. We haven’t been able to cross paths. So, the whole goal was to shine a light on this city, because we do have talent and you don’t have to come through Nelly to be successful, just like you don’t have to come through Jay-Z or Puff Daddy to be successful out of New York. Just like you don’t have to come through Dr. Dre to be successful in LA.

In a lot of these cities, people thought you had to come through so many people, like YG said, “The only one to do it out the west without Dr. Dre.” So I think St. Louis is about to explode with a lot of great music. I think our second wave—I would say second and third wave—is going to be massive.

You did Verzuz in the original Instagram live format. Have you talked to Swizz about re-exploring a battle with Luda in the new format? The live format?

Nah, we haven’t talked about it. But I mean, if it’s something that comes up, of course it’s a conversation when you talk about good brothers, Tim and Swizz. I’m really happy for them, because again, having that creative mind, these brothers created something that’s unmatched. I believe lemonade came out of lemons. We don’t get Verzuz like this, if not for the pandemic. We probably don’t get it and I don’t know. We’ll see.

Is there anything else you want our readers to know?

I just want to thank them. Thank them for all the love, all the support. All the ways that they done held it down for Nelly. And not just Nelly, held it down for St. Louis and for other people that came out of here. And again, keep your head up, be on the lookout for new things coming out of the Lou, new things coming out of Derrty ENT. We’re going to rock out. And again, thanks BET for the recognition.

SHARE THIS STORY