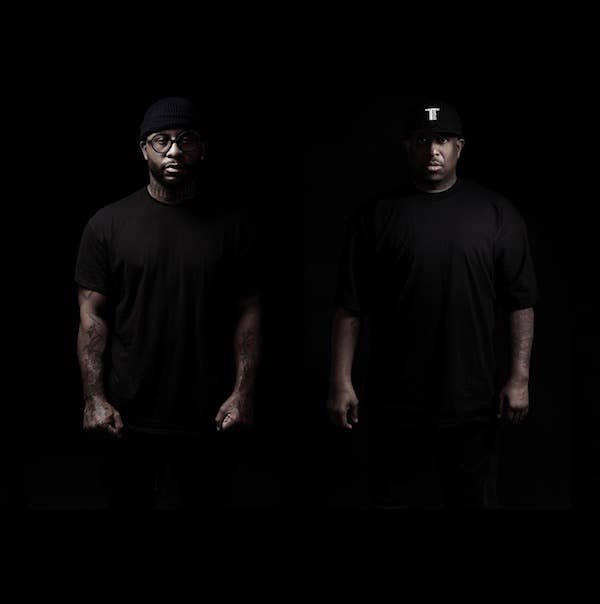

When legendary producer DJ Premier first teamed up with Detroit rapper Royce da 5'9" for the 2014 album PRhyme, hip-hop heads were beyond excited. The idea of Preem forming a duo with another MC for the first time since Gang Starr would have been thrilling no matter what. But when it was the pairing who previously brought us the 1999 classic "Boom"? Well, that was all most people needed to hear.

But PRhyme works differently than any other project the duo is involved in. They take a bunch of music from just one producer (Adrian Younge for PRhyme, and Antman Wonder for the brand-new PRhyme 2, out this Friday). Premier then samples and flips it in his own inimitable way, and Royce raps on top of the end result.

Complex sat down with Royce and Premier in mid-February, after hearing the new album (which you can check out for yourself below). The guys talked about everything from Royce’s sobriety to Preem’s meetings with movie stars, and mentioned how one of their new songs was inspired by a Complex series. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Premier, in the intro to the album you say that PRhyme is about taking an artist’s sound and putting it in your universe. So does that mean PRhyme can exist outside of Royce?

DJ Premier: No. Never. It has to be me and Royce. That’s why I said the ‘P’ [in the group name] is for Premier and the R is for Royce 5’9”—that’s why they’re capital. Royce came up with the idea to name us as a group.

Royce, the new song “Black History” really grabbed me. The tune overall is about your hip-hop predecessors, but then you talk about three generations of your family mistreated by the health system. Why did you address that on a song that otherwise pays tribute to past rappers?

Royce da 5’9”: I started doing a lot of thinking back on things that happened to me when I was young that I didn’t necessarily pay attention to, or things that I wasn’t able to pay attention to because I was too young. Talking to my mom and hearing these stories, I just thought it was kind of symbolic the way that we were treated when I was in the hospital when I was born. It seemed like the decisions were contingent upon my dad’s health insurance status and to me, that was my first experience with big business, even though I wasn’t fully aware of what was going on.

Essentially, the same thing happened to me when I got in the music business: I almost got chewed up and spit out. It was just like, we pull you in, we treat you like you’re important, we court you, we give you a bunch of money. But when you can’t deliver what we want you to deliver, we release you. So I felt like that was interesting. I tried to figure out a way to connect all of these little nuances with Preem’s journey in the way he met Guru and the way that they formed Gang Starr and became a classic group in hip-hop.

He was not even in a space where he was even willing to consider getting into another group after the passing of Guru. When I finally approached him about it, he considered it on the strength of me. It’s like all of our paths just keep crossing.

One of my first experiences in hip hop was at [Premier’s] D&D Studios when I did the freestyle for Tony Touch. Billy Danze was there, a lot of DITC [the Bronx-based Diggin’ in the Crates crew] was there. Jayo Felony was there. Preem wasn’t even there. I was there with Marshall.

I actually [once] wrote a letter to D&D Studios, asking if I could record at the studio.

Did you ever get an answer?

R: Nah, I never got one. [To Premier] Why you ain’t answer me, man?

P: I ain’t read the letters. [Laughs]

R: I just felt like all of that shit is kind of connected in a way, like the way our paths crossed, and what can happen when those paths join together.

It’s funny you mention DITC, because there’s that extended DITC tribute in that song, and you use Big L for an outro of one of the tunes. It seems like that crew figures heavily in the way you guys connect.

R: They almost raised me. I grew up looking up to Showbiz, AG, Diamond D, the whole crew. Fat Joe was one of my idols that’s living right now. He doesn’t get the credit he deserves because he’s the only person in music right now, in hip-hop, that’s doing something that’s never been done before, and people don’t even realize it. He was making records before me and he’s still able to make records that resonate with the youth without having to change his formula. He sounds the same to me. He has an impeccable ear for beats. He’s not supposed to exist in hip-hop right now.

Royce, do you approach a PRhyme project differently than an album with just your name?

R: Yes I do, but not always on purpose. It’s something about the formula of pulling everything from one source. When you’ve got a sound bed that’s consistent, and you’re working with one producer who’s not just a beat maker but a producer, it just makes it really easy.

When I approach Slaughterhouse stuff, I’m kind of like the producer in a way because I’m the guy in the group that oversees the records, so my workload is different. When I‘m doing Bad Meets Evil stuff with Marshall, he’s kind of overseeing the records, so my workload is different. When I’m doing my solo stuff, if I’m not working with Mr. Porter, my workload is all me, so my brain is automatically functioning in that capacity. With PRhyme, it’s more fun than work.

You rap about your alcoholism throughout the album—sometimes as a punch line, sometimes more seriously. What does talking about it so publicly accomplish for you?

R: It’s very therapeutic. It’s to another level now because due to social media, I’m able to interact with people who it’s affecting. They’re very vocal and descriptive as to how it affected them, and what good has come out of it. I’m to a point now where I’m in my DMs all the time talking to people like a therapist. It’s literally like, “Yo, I have a problem. How did you stop?” I always love answering that question because if you think you have a problem, nine times out of ten you probably have a problem.

Sometimes you gotta let people know, the same way Marshall let me know, that when you finally get to a point where you’re willing to admit that you have a problem, that’s when you’re at your strongest. A lot of people view it as a weakness because you’re admitting to yourself that you’re powerless over something. So it makes you feel like, “Damn, I’m weak. I can’t control this shit. My friends can control their drinking but I can’t control mine.”

In the world of sobriety, we view that as your strongest point because you’re no longer in denial. You’re willing to admit it. I equate it to a man admitting when he’s wrong about something and being willing to say “I’m sorry.” You know how hard it is for somebody to use those words? It’s no greater feeling for an artist or a creative person to write something and it resonates that well with somebody.

Have you found new inspiration within PRhyme’s musical limitations?

P: Yeah, because a lot of the stuff that Antman does, when you're dealing with one person's catalog or sound, there's almost gonna to a certain degree be...I don't wanna put it in that type of box, but almost sounding the same. I'm not digging from a Jack Bruce record, then going to get a David Axelrod record, then grabbing a Stanley Turrentine record and a Crusaders record and making an ill hip-hop beat. The challenge is, where can I snatch a part of what they've done that’s not even normal? That's the fun part.

I like to excite them. Even with Adrian Younge on the first PRhyme album, he was like "Man, I made my stuff so people would take the break part. You didn't touch any of that. You went to the edge without jumping over the cliff.” That's what I'm known for. I want unexpected. That's the challenge and that's the fun part of being a producer.

Since we’re at Complex, I have to ask about the song called “Everyday Struggle,” about the show that films two floors up from here. What did seeing the back-and-forth between Joe Budden and Yachty spark in you?

P: It's the whole narrative that's been created, these lines that are drawn between artists who don't make similar music. To me, it's all hip-hop. I feel like it's too many OGs criticizing and not teaching. The young’uns, a lot of them, they don't know any better. When you're in your young 20s, a teenager, you need to be taught certain things. And you're automatically gonna put your defense mechanisms up if you feel like you're being critiqued and you're not pulling anything from it. It also creates a lack of respect for those that came before you.

R: What's happening now is the kids are just coming in and the new narrative is, "We don't listen to the OGs at all. Fuck them. We doing shit different this time." But you know that's not true. They want the credit for taking and evolving the music. They're just using the wrong narrative.

We originally wanted to put Lil Uzi Vert on [the song]. I've always been one of those people that say, "Yo, instead of complaining about the state of things, why don't you just take the necessary steps and become the change that you wanna see?” And I feel like this is the perfect kind of project: the world that we speak to, to blend that together with the world that he speaks to, to show everybody that it doesn't always have to be division. As long as you can come together and make something, that's good. If we make it good, it'll unify the fans in a way. Hip-hop is always supposed to be one of the only ways to unify races and everything, and now there's all these barriers. That song just spoke to that whole feel.

Using Joe as an example and using that title, I think it puts you in the right mindframe to look at what I'm thinking about. That is a huge platform to talk about the narrative that I'm talking about. I'm a huge fan of the show, and obviously Joe is a friend of mine. I felt like if we could have pulled [having Uzi on the song] off, we would have got the point across even more. He originally was supposed to sing that hook, and he was like, “I want to do a verse.” He and Preem had been in contact, but, you know, scheduling.

P: I gotta shout out Showbiz from DITC because when Uzi Vert said he didn't wanna rap over “Mass Appeal” on Hot 97, everybody was hitting me up like, "Yo man, you need to diss that dude for life.” I was like, "Why? He doesn't have to rap over my beat."

I said that on Twitter: "He doesn't have to rap on it. Whatever he decides, he decides." And 60 seconds later, Uzi Vert replies and goes "Yo OG, I would've rapped if it was the ‘Full Clip’ instrumental." Right there I hit follow. I thought, that's dope that he knows that.

He DMd me and he said "Yo big bro, everybody thinks I'm not a fan. First of all I'm from Philly. Why wouldn't I know? I just don't do the style of music that y'all do, but I'm hip to everything." He said, "We need to get in the studio and show people that we ain't on this divide thing. Teach me whatever you need to teach me. I'm willing to learn." That had me open.

I remember telling Showbiz about it. He's like "Yo Preem, do that record with that dude. That's a good thing." We were just really expecting that one to happen. It just didn't pan out time wise, but I had mentioned it to a couple people and they're like "Man, don't ruin the album with that dude." It's like, how are we ruining it? If it's with us, it's gonna be right. That's more reason we wanted to do it, and show people why they're wrong. I'm down for the challenge. So I was really looking forward to that one.

Royce, were you worried about losing a step artistically when you went sober?

R: I was worried about everything. I think we're all naturally afraid of change on some level. You can get yourself into a comfort zone of something being the same every single day.

I literally turned my life into a drinking ritual. If I'm at home, I'm waking up, getting ready. My assistant comes and gets me. We take the same route to the studio every day, so by the time we get to the first light I start jonesing for liquor. I usually stop at this liquor store—we call it triggers, it's a trigger. So when we get to the liquor store I order the same thing: a liter of 1800 Silver or Patron Silver. We get to the studio, I automatically wanna drink as soon as we walk in there. As soon as I smell the studio, I immediately wanna drink.

So when you take all those things away, you just notice them. You get to the light and it's just, I gotta get myself used to not stopping at the store. I wanna drink right now, but I can't. It's gonna kill me. I get to the studio and it's the same thing, you gotta just wait it out.

You gotta get yourself back used to doing everything, not depending on the substance. I was worried about everything. I started drinking when I was 21, but even the worst of worst days as an alcoholic, the Bad Meets Evil album, we recorded the whole thing in Marshall’s studio, and I never had a drink in that studio while he was there. But in my mind I would know I'm gonna drink later, so it's no big deal.

Being sober and writing—not drinking, but knowing I'm not drinking later either—that weighed on me a little bit. I had to get myself used to that. I knew I was gonna be way clearer. I knew the fans would hear how clear I am, and it doesn't necessarily work for everybody. When T.I. first got sober, I felt like it was missing something. It took him a minute to get that sharpness.

P: Not only am I dealing with the sober Royce so that I don't know what to expect because this'll be new to me, he [also] has a new style of production. That's like strike two. Now, the next thing is the album could crash and not just be hot.

I was in L.A. for the Golden Globe Awards. Everybody's in town. I hung out with Joaquin Phoenix, the actor. He wanted to meet me through another actor friend of mine. He wanted to meet in this dark hotel. He hates attention. He's shy to be around people. When he saw me, he was like,"I got so many questions I want to ask you, but I don't want to bother you." I said, "Dude, go ahead." He said, "When you did "Aiiight Chill" on Hard to Earn, did you call everybody and say just leave that mess?" He wouldn't ask regular questions about "Mass Appeal." He's talking about "The Planet." He’s talking about, "When you did 'Brainstorm,' it faded while you're still doing the end of the verse." Those types of people I like to talk to because you really know my stuff, and it's more fun.

When that happened, he goes, a friend of mine is here that says she knows you very well, and she's hiding behind this curtain. She wanted to see if you know her, she said y'all are really close. I was like, "Who?" And he says "Come on out Amanda." I turn around and it's Amanda Demme, who's Ted Demme's wife. Amanda had the illest hip-hop spot in 1990 in New York. Everybody used to go there. She called it Carwash. Everybody who was anybody was at that spot every Monday. So when I saw her I'm like, yoooo, I haven't seen her in like 15 years, maybe more. She's like, “Yeah I do art now. I'm a photographer. You gotta check out my stuff. Whatever you're working on next you should let me be your photographer.” [Demme went on to do the artwork for PRhyme].

Royce, what does it mean to be in a duo with this guy?

R: It means everything. For him to even do one beat for me, it was surreal. It was like a dream come true. I always told myself, if I ever got in a position where I felt like I wasn't insulting Preem to ask him to do something like that, I'd do it. But I would have to get my weight up and my time in the business. I can't come to him as a new schooler and ask him nothing like that. That's blasphemy. I would actually have to be a veteran myself.

Timing is everything. It just came at a time where it was needed in hip-hop, it was needed for me. When I first got sober, I asked, "What is the first thing I can do coming off of this long layoff of not releasing music and not making music?" And I thought of the young Ryan Montgomery at the Ebony showcase at just 18 years old, rapping for the other rappers, just wanting to tear up MCs. How can I do a reintroduction? So when the idea came across my desk, I ran it by Preem and it just so happened he was with it. I caught him at the right time, and we went with it. I've been building from that point ever since, and it means everything to me. It's the beginning of a reinvention for me.

What else is coming up for you two?

R: I got a solo album. I'll be announcing some dates really soon. Right now I'm just gonna focus on PRhyme. We're definitely looking at touring. We don't have that put together just yet, but the conversations have started.

P: The 20th anniversary of Moment of Truth is March 31, so we wanted to do a tribute in major cities like Detroit, Chicago, LA, and New York where we do the entire album intro to outro, and we have all the guests on it—the only one that wouldn't be able to make it is G Dep, because he's locked up.

It's crazy ’cause Guru’s son just texted me saying he has an issue musically he needs my advice...

R: He texted me for advice too.

P: Guru's son is very quiet and he told me, "Hey man, I wanna know your opinion." So I said, let me hear it. I'd love to work with his son. Plus we handle his estate so they're doing real well. His son's eating off of the legacy of Gang Starr.

We'll be doing a couple other things that I can't talk about yet. But it'll be a great surprise.