This story was originally published in the December/January 2012 issue of COMPLEX.

Drake isn’t happy. Not in an existential way or anything. He’s not upset about the direction his life is heading, or about the subliminal potshots rappers keep sending his way. Nah, he’s unhappy with how his photo shoot for this magazine is going down. Which is surprising because it’s a bright, unseasonably warm October afternoon in downtown Toronto, and things were going so well.

We’re perched on the roof of the posh Thompson Hotel where Drizzy’s being photographed overlooking his city like a feudal lord surveying his kingdom. To his left are cranes modernizing the largest city in Canada. To his right is the Rogers Centre, the convertible stadium seen in his “Headlines” video.

Suddenly Drake tells the photographer to stop and calls for his manager, Oliver El-Khatib, 25, co-captain of the creative team October’s Very Own. Canceling a cover shoot at this stage would be a serious waste of time and money, but Drake doesn’t give a fuck. He wants things done his way or not at all.

What Aubrey Graham, 25, and his OVO crew are trying to build here is—excuse the cliché—a Toronto movement.

“For Drake we have these budgets where we can do videos and shoot photographs by whoever the fuck we want, the hottest guys in New York or L.A.,” Oliver explains. “But I’d rather take Hyghly and Lamar, two kids who are 20 years old... I’d rather build up their portfolios and help them get on and do this video. So now they’ve done ‘Marvins Room’ and ‘Headlines,’ and hopefully they can do more videos. They shot all Drake’s album artwork.

“We have this little fun factory in Toronto where there’s music being made, there’s art being done, videos being made, we’re starting to work more on our clothing,” Oliver says. “It’s kind of fun, you know? We’re giving opportunities to kids who deserve it... It’s different because everything we’ve done has worked.”

“There used to be a conversation in the Toronto hip-hop scene,” says producer Noah “40” Shebib. “You would [ask] on a regular basis: Who do you think is goin’ to do it? Do you think it’s even possible? Do you think a Canadian rapper could ever blow up in America? That conversation doesn’t get had anymore.”

Since breaking into the mainstream with So Far Gone, the 2009 mixtape that became his hip-hop baptism, Drake has positioned himself as one of music’s premier players. This coup was facilitated by his alliance with Lil Wayne, who damn near kidnapped the young Canadian, taking him on a nationwide tour before throwing him on numerous tracks. When Weezy reported to Rikers Island in March 2010 for an eight-month bid, Drake and his fellow Young Money/Cash Money signee Nicki Minaj stepped up as the label’s primary breadwinners. His moody, emotionally honest debut, Thank Me Later, hit No. 1 on Billboard, selling 447,000 in the first week, and birthing three Top 20 hits.

Drake’s introspective, self-effacing lyrics—usually delivered in clever, succinct couplets—reveal the inner machinations of many dudes in their mid-twenties: the quest to live life to the limit, not just survive a nine-to-five; the balance of carnal desires with sincere compassion for women’s feelings; the struggle to act responsible when all you want to do is blow your paycheck on lap dances, liquor, and weed.

With gangster rap in decline, and Kanye refashioning the parameters of rap stardom, Drake arrived right on time. But his success has made him one of the most polarizing figures in music. Lil Wayne anointed him the best rapper alive, and he’s rhymed alongside some of the greatest—Bun B, Jay-Z, Jeezy—yet some insist that Drake isn’t hip-hop; that he’s too soft; that he sings too damn much; that he doesn’t sing enough—and should stop rapping; that he wears silly outfits.

"I don't give people Many reasons to dislike me. They have to find that sh*t."

“They nitpick at everything,” he says, shaking his head. “I can’t do anything. All they want me to do is dress so they can make fun of me. Otherwise, it’s hard for them. I don’t give people many reasons to dislike me. They have to find shit. They’re like, ‘Aw man, sweaters! He wears sweaters too much.’ Like, what?”

No other good rapper—because, let’s be honest, Drake’s one of the best doing it— draws the same amount of love and ire. It’s enough to drive a person crazy. For every three who applaud him—Nas has likened Drake to “fresh water on dry land”—there’s one looking to shoot him down.

Most recently it was Pusha T, the newest G.O.O.D. Music recruit, throwing thinly veiled jabs (“The swag don’t match the sweaters”) in a freestyle over Drake’s Jai Paul–sampling “Dreams Money Can Buy.”

Which is not to say that Drake doesn’t play the same game. When he dropped “Dreams” last May, he ruffled feathers with the line, “I feel like it went from top five to remaining five/My favorite rappers either lost it or they ain’t alive.” Since he once said he’d cry if Jay Z died, it’s safe to assume Hov would make his top five. But when pressed, Drake neither confirms nor denies whether Jay and Kanye were targets.

“It wasn’t meant to be a shot at the five rappers that I love,” he says. “I’ve never even sat down and pieced together a top five before. I just feel like I’m really good right now. And I’ve never felt like that before. I’ve always felt reluctant to say anything like that, but I’m very confident in these new raps that I’m about to give the world.”

Drake’s also very confident in the strength of his YMCMB team. When he says, “They trying to bring us down/Me, Weezy, and Stunna,” he may be referring to “H.A.M.,” the first single from Watch the Throne, on which Jay Z took unnamed rappers to task for having “baby money,” and not even as much as his lady. Lil Wayne wasn’t the only listener who took that as a reference to Cash Money CEO Bryan “Baby” Williams. Five months later on DJ Khaled’s summer banger, “I’m on One,” Drake proclaimed that “the throne is for the taking” before advising listeners to “watch” him take it.

Careful listeners may have noticed that Kanye West (who’s worked with Drake in the past) employed the “hashtag flow”—which Drake popularized—on “Otis,” the biggest single from The Throne’s recent album. Many wondered who he was referring to when he said: “Niggas talking real reckless/#Stuntmen/I adopted these niggas, Phillip Drummond them.”

The cold war heated up when Wayne returned fire on “It’s Good” from Tha Carter IV. In the song, which also featured Jadakiss and Drake, Weezy presumably talks about kidnapping Beyoncé. Jada declared neutrality immediately after the song leaked, stressing that he had no idea what Lil Wayne was going to say. His denials sounded reasonable enough, but what about Drake? “I’m his soldier,” he says, affirming his loyalty to President Carter.

Still, Drake does his best to remain diplomatic—sort of. “Rapping is about being young and doing your thing and being fly,” he says—the implication being that if older rappers catch feelings, so be it. “I’m sure people took it that way and that’s good, man. That’s great. Wake the fuck up. I hope it makes you go harder. I hope it makes you get mad at me and write a song with me in mind. I hope Kanye’s verse on ‘Otis’ was with that in mind. Everyone tried to tell me ‘Oh Jay is going at you.’ I don’t hear it, but I hope it was man, that song is fucking incredible. Making each other go harder, that's what this shit is about.”

"EVERYBODY’S LIKE, ‘GET THE F*CK OUT OF HERE WITH THAT SH*T,’ BUT I’VE DONE A LOT FOR THE STREETS."

Still, Drake does his best to remain diplomatic—sort of. “Rapping is about being young and doing your thing and being fly,” he says—the implication being that if older rappers catch feelings, so be it. “I’m sure people took it that way and that’s good, man. That’s great. Wake the fuck up. I hope it makes you go harder. I hope it makes you get mad at me and write a song with me in mind. I hope Kanye’s verse on ‘Otis’ was with that in mind. Everyone tried to tell me ‘Oh Jay is going at you.’ I don’t hear it, but I hope it was man, that song is fucking incredible. Making each other go harder, that's what this shit is about.”

The very fact that rappers with more mileage in this game see Drake as worthy of dissing is noteworthy. If the adage “never shoot down” holds any weight, Drake should interpret all this verbal turmoil as high praise. No one’s taking the time to go at Wiz Khalifa’s neck, or to chop Big Sean down to size.

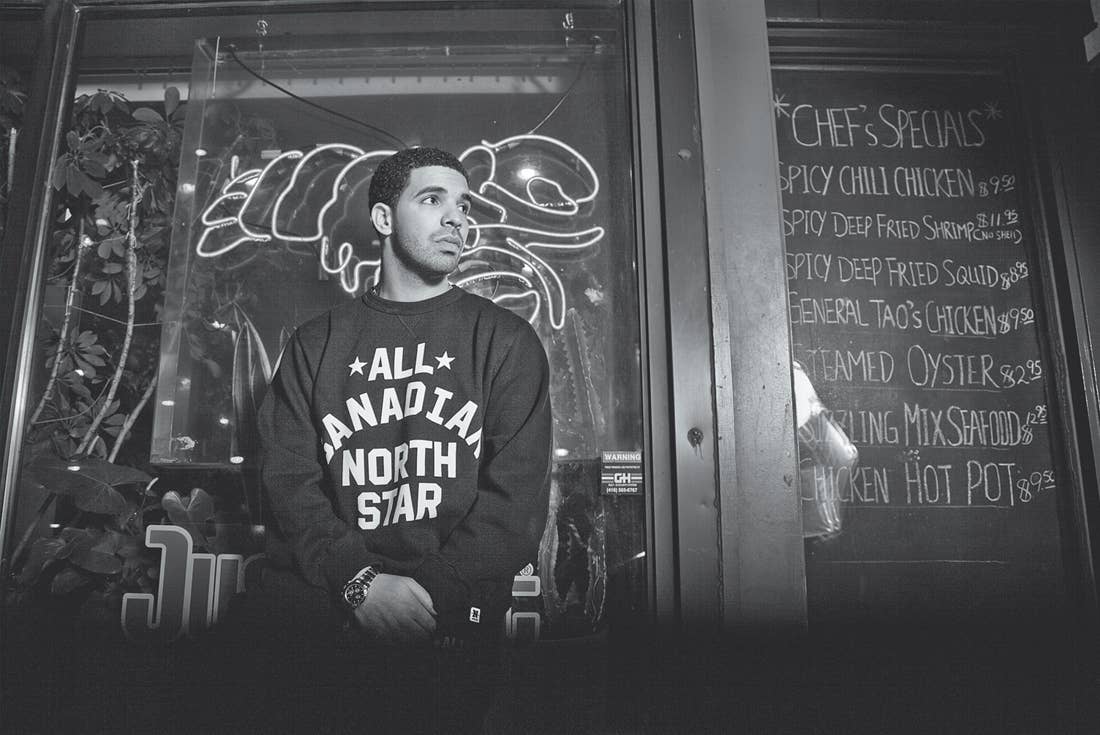

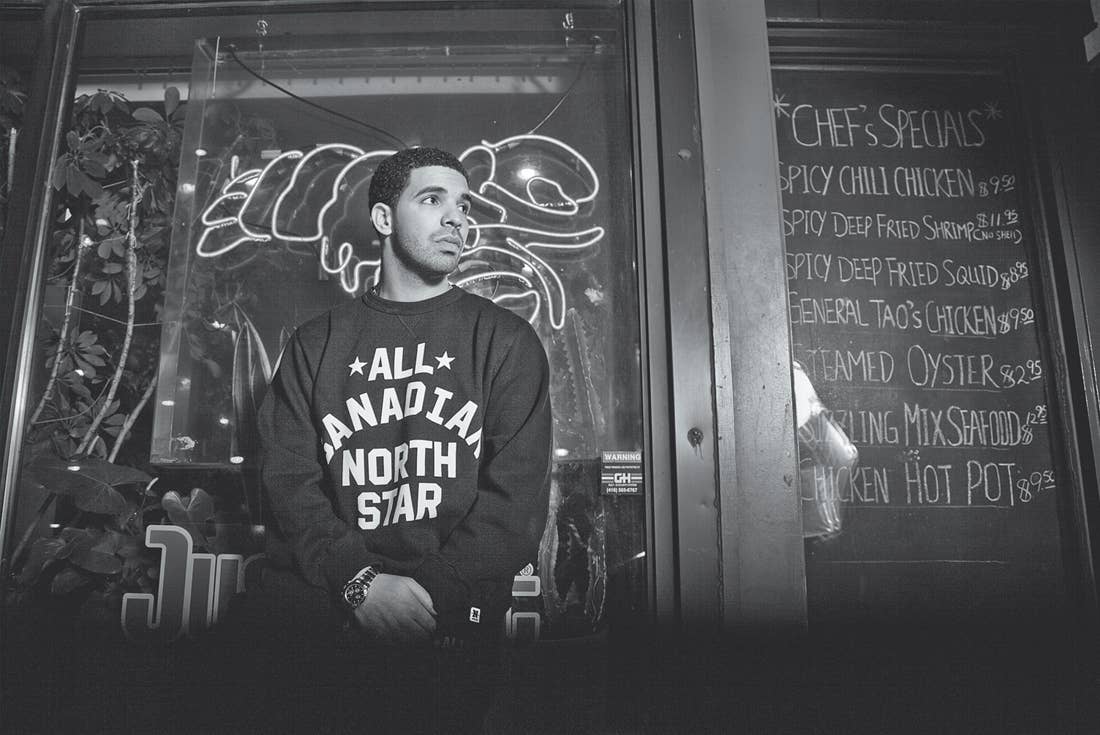

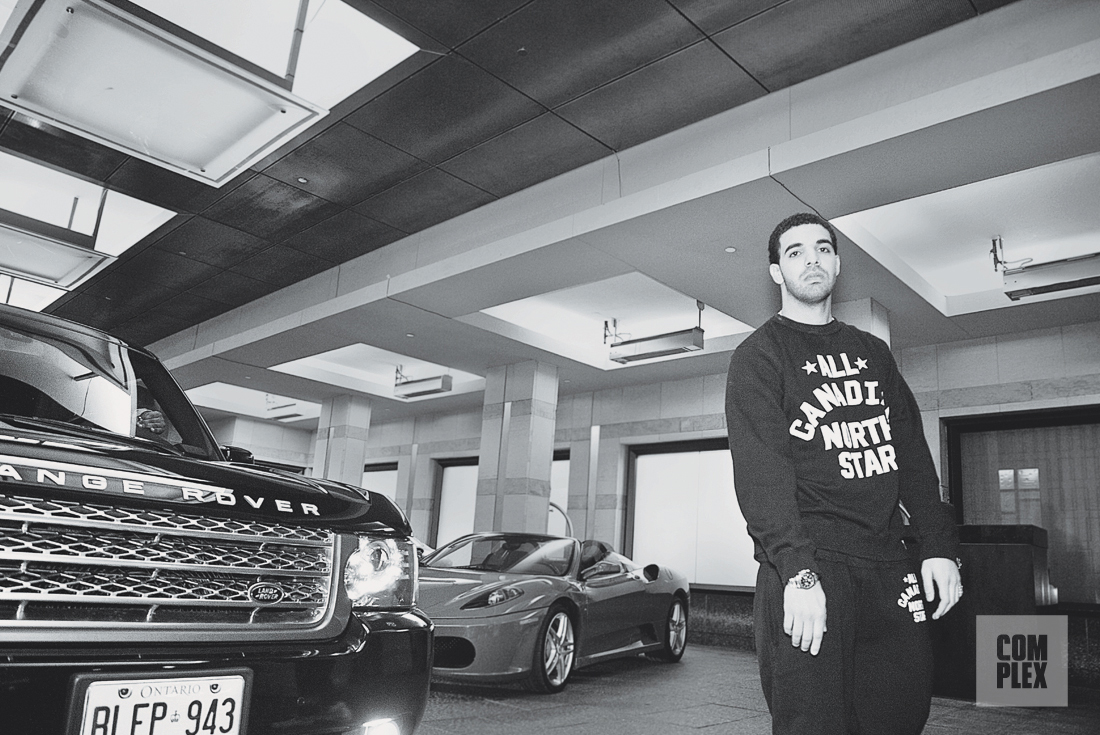

Dubbed “Toronto’s most exclusive hotel,” the Hazelton is a mix of old money and new aesthetics. Rocking a gray North Star sweatshirt, baggy stone-washed denim, and Timbs, Drake stands on the sidewalk waiting for the rest of his crew to arrive while wealthy white businessmen and their spouses steal looks at the young rap star. He waves politely and smiles.

We move as a unit to the Hazelton’s ONE restaurant and grab a table. Drake tells me he would have liked to do the interview at his apartment but he’s having an experience shower installed.

A what?

“It’s a shower that’s lit by all LED lights,” he explains. “It has 10 jets, an overhead, and it sprays out lavender or whatever scents you want. It’s something I’ve always wanted.” Some guys buy chains and watches; Drake cops showers. His newfound affluence brings to mind a line from “Headlines,” the first single off his new album, Take Care: “I exaggerated a bit, now I got it like that.”

“Before it was foresight,” he says. “I used to rent a Phantom for $6,000 a month. I would tell girls I owned it or whatever. You know, I would exaggerate. But now it’s all good.”

Shit, it must be. The “Headlines” video ends with Drake standing alone in the Rogers Centre—previously known as the SkyDome—looking to the clouds as the roof opens. I remark that shutting down the SkyDome must have cost a lot. Drake says the video only cost $60,000. “It’s always a phone call out here,” he says with a smile. “Anything is a phone call.”

More than the drop-top stadium, the video’s most talked-about image was Drake draped in all-black Nike apparel, surrounded by two groups of ominous-looking dudes in black hoodies. Blog commenters derided him for renting some thugs to make himself look tough.

But the guys in question are not some newly assembled goon squad. Most come from two of Toronto’s worst neighborhoods, Malvern and Galloway, which have been warring for the past few years. “There’s a lot of people lost in that situation, and through having mutual friends in both of those hoods, we were all able to come together, shoot that video, and immortalize that moment,” says Drake—visibly perturbed that he has to explain himself. “I don’t brag about my hood stories. Everybody’s like, ‘Get the fuck out of here with that shit,’ but I’ve done a lot for the streets out here.”

“Everybody knows Drake isn’t hood,” says Niko, his right-hand man and confidant. Neeks, as the crew calls him, is a quiet, bespectacled dude who met Drizzy back when he was pushing his first mixtape, Room for Improvement. Neeks says Toronto rap used to be much more street-oriented. Kardinal Offishall, Saukrates, and Choclair were the big names. “Drake came and flipped it and said everything that a hood guy can’t say. I guess that’s why people liked him.”

Drake has no delusions of himself as a gangster. He knows he’s at his best when paring down real-life events and emotions other rappers would never tackle. “Any musical sound is real to me,” Drake says as another round of drinks hits the table. “It doesn’t matter if it’s from like Lana Del Ray all the way to Future from Atlanta or A$AP Rocky. Sonically, you can do whatever you want. That’s the beautiful thing about music: you get to make a choice. The more you can start pinpointing pieces of your actual life and start pulling it into your music, people will be like, ‘Damn, that’s something I’ve only thought about, but this guy put it into a song.’ ” He mentions the drunk-dialing ditty “Marvins Room” as one example of a song drawn from his daily life.

But if music is a blend of reality and artistic license, where does Drake’s talk about catching bodies fall? “Who’s going to catch a body with all these niggas rapping about murder?” he asks. “Who’s really putting a body on a gun?” C-Murder and Gucci Mane come to mind, but I say nothing. “When I say, ‘You’re going to make someone around me catch a body like that,’ that’s something you can ask them about.” He points to his boy Chubbs—the one who’s “in love with street shit.”

“Everybody wants to poke and jab at Drake because they don’t feel like he will throw back,” says Chubbs, who met Drake nearly four years ago. “But nobody around here is going to let something happen to him at any time, especially me. I’m not ever going to let nothing happen to him. If it’s going to happen it’s going to happen to me first.”

Drake never looks for trouble, but he’s not going to run and cower if it comes looking for him. “If somebody wants to bring a problem to me, it’s strictly based off of their immense amount of hate for me,” he says. “It’s never because I’ve sparked that using my voice, my image, or my outlet. I never use my outlet for confrontation or negativity, ever. I always try and give people music to ride to and music to enjoy. All I ever ask in return is that it’s mutual love.”

Is that too much to ask? Maybe. But what can you do when the love turns to hate? “I’m ready for whatever,” he says. “I don’t give a fuck. I want to move through life in the most non-confrontational way possible, but I’m not a pussy. Don’t ever get that mixed up.”

There is one thing that Drake fears though: “Dying, before I accomplish all this,” he says as the waiter arrives. “That’s it. My father taught me: ‘Don’t fear any man. Don’t ever fear another person.’ I don’t get myself mixed up with stupid shit. I get a lot of love. I don’t feel tension. I stand 6'2". By no means am I the most threatening guy in the rap game, but there are very few people who will come up and say that shit to me in person. It’s always all smiles. That’s one thing I do not fear, anyone in this game. Nobody. Especially none of these guys that are paid to talk shit.”

“I do not fear anyone in this game. Nobody. Especially none of these guys that are paid to talk sh*t.”

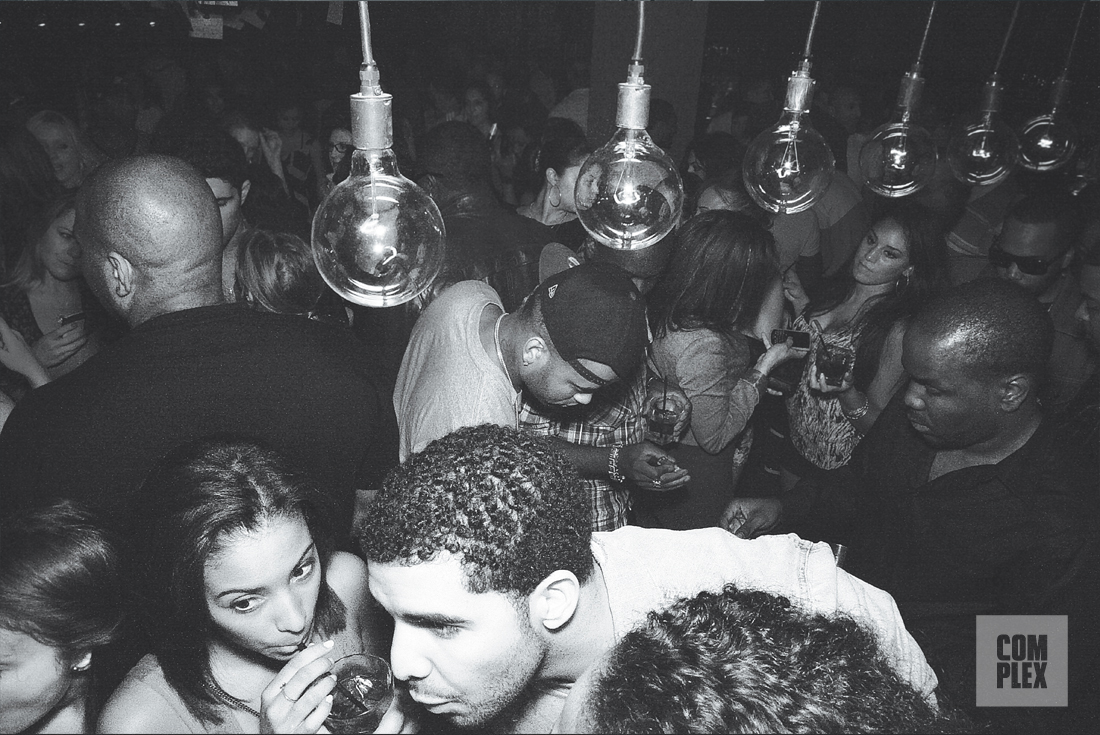

The Goodnight Bar in Toronto is impossible to find if you don’t know where to look. Photos of dead dignitaries hang in the dimly lit, wood-paneled space. Drake shuts Goodnight down so it’s only his boys and me—oh, and a female friend who joins us later. Drinks flow courtesy of Mr. Graham. Blunts are rolled, sparked, and passed to almost everyone except Drake. It’s a good time.

When Drake talks about his Toronto movement, he’s primarily speaking about the people in this room. He’s glad to provide his friends with the means to better their lives. “All these people are happier than they’ve ever been,” he says. “They can afford to get their own place, get their own car, or maybe it’s just having a jacket, feeling a part of something. I’m embracing that role.”

Drake’s continued to put on for his city by shining light on a Toronto- based singer named Abel Tesfaye. You know him as The Weeknd. The 21-year-old with the wicked falsetto has put out two strong mixtapes, further establishing October’s Very Own as a force. “I wasn’t like ‘Yo, I’m looking for new artists,’” says Drake. “The Weeknd was presented to me, and anybody with any form of an ear can understand why I had to fully embrace that.”

“It’s our responsibility if there’s talent in the city to shine a light on it,” says Oliver. “That’s our duty. There were a lot of people that came before us that were extremely talented but I feel like they bred a generation of kids that didn’t fuck with them. That’s kind of the Toronto mentality: ‘Nobody respects you until the Americans respect you.’ But now I feel like we’re going to do the right thing and if there’s talent here we’re not going to pretend it doesn’t exist.”

Drake may only have one artist under his wing, but the number of women he’s associated with grows by the day. He’s talked at length about his heartbreak with Rihanna and his love for Nicki. Though he tries to keep mum, it’s impossible to tamp down speculation. He was recently snapped playing tennis with Serena Williams. Surely there’s more to their pairing than a couple of aces, right? Drake smiles and gives a ready-made response: “I really, really love and care for Serena Williams. She’s incredible. That’s someone I’m proud to say I know. She’s definitely in my life and I’m in her life. It’s great to watch her play tennis. Very impressive.”

When asked about Quincy Jones’s Harvard-educated daughter—and star of Parks & Recreation—Rashida Jones, Drake pauses, then offers: “Rashida has a beautiful, beautiful spirit. So talented, so funny. I met her at Rihanna’s birthday party. I was DJing and she liked my set.”

Around 2:30, Drake closes his tab, puts on his hoodie, and gives daps to everyone in attendance. The bar empties out into the alley and then into the street where a motorcade of Range Rovers waits to shuttle everyone home. Though they spend a great deal of time together, everybody in the crew takes time to say goodnight. This is what Drake means when he calls these people his family.

Like Wayne and Jay Z, Drake intends to construct his own kingdom. A domain separate from the liars and haters. One where his friends lift each other up. But for that to happen, one needs a little Dame Dash and Birdman in them. You have to not give a fuck about anything.

Take Care, he says, will be the soundtrack for that metamorphosis. “Take Care has a lot of meanings,” he tells me. “It grew into a whole mind set... Never forgetting the past, but just embracing this moment and saying ‘take care’ to any doubt, any second-guessing. This is it. I have a great album. I have a great team. I have my visuals together. I have a great live show—those are all things that I know. I’m not doubting myself. I’ve never been in that position. This is my first time. And I hope I’m right, because I know I’m right to me.”

That’s why Drake walked off the set earlier. Had the shoot taken place anywhere else, or a year earlier, he would’ve been cool. But not repping the way he wants, here—in his own city? Nah, son.