Public art can be for anyone in the same way their meanings can differ for everyone: a counter to oppression, a contour of possibility, or simply an object to lean on.

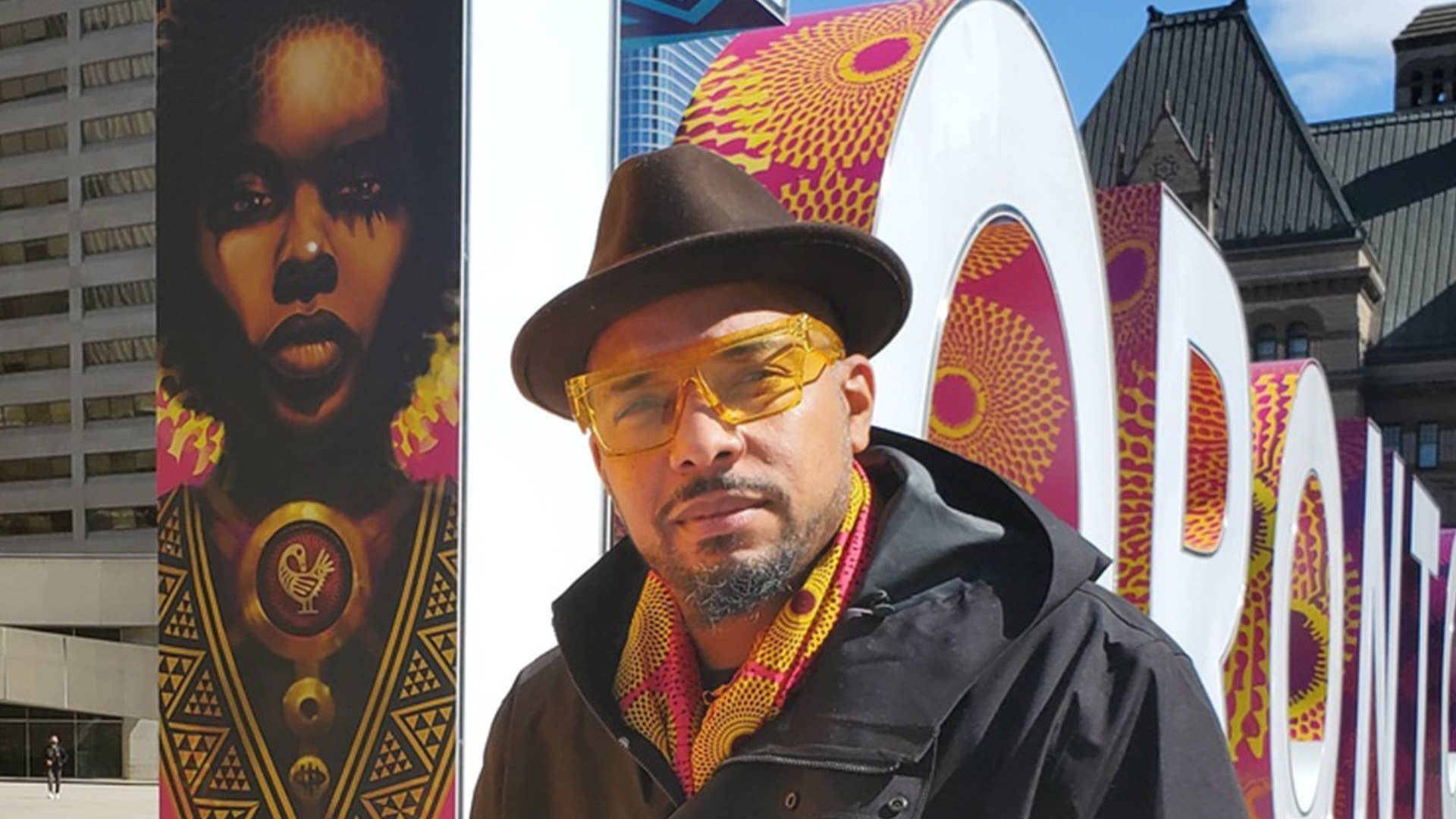

“Similar to my work with the Toronto sign, what I often try to do is a form of alchemy,” says Danilo Deluxo, the artist behind the first vinyl wrap on the very leaned-on 3D Toronto sign at Nathan Phillips Square. “I take all that negativity and lift it. I always want to make sure we’re presented in a bold, brilliant, and beautiful way.” Or in other words, the meaning is the meaning, rested backs or not.

Despite Deluxo’s footprint on one of the most plainly recognizable landmarks of the city—fashioned as a symbol for Black excellence—the Toronto curator and multidisciplinary artist joins several other BIPOC artists often celebrated more for their craft over name-dropped praise; the art flaunts for itself.

Deluxo’s award-winning work is part history lesson, and part possibility. Through the framework of Afrofuturism, his pieces are an examination of Black identity beyond the mundane limits of the everyday. To that effect, between 2013-2017 he served as the curator and creator of Black Future Month, an annual Afrofuturism exhibition that amassed international recognition and acclaim. And as a practicing artist, he’s produced murals and art projects globally as a member of Collective XYZ while also collaborating with BSAM Canada (The Black Speculative Art Movement).

It’s been a decade’s long venture for Deluxo that’s now in a state of continuance. His latest: a curation of a massive, year-long street art exhibition known as ALL CITY SHINEwith Downsview Park as the hub. Featuring 25 BIPOC artists and including ALLSTYLE—a 360-foot long mural of nine talented artists across the spectrum that explores identity, ancestry, and strength—the event is creating a space for Toronto’s BIPOC artists to shine as one.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This is a question I ask everyone, but how have you been dealing with the past year and a half?

Automatically, it’s been heavy. It felt like an automatic thing last year to ask someone how they were doing and automatically understand that we were all going through it. I’ve been balancing everything with the reality of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd which made it an extra heavy time. But to be honest, at this point my wife and I are in a great place. We just had a baby.

“Similar to my work with the Toronto sign, what I often try to do is a form of alchemy. I take all that negativity and lift it. I always want to make sure we’re presented in a bold, brilliant, and beautiful way.”

Aww man, congrats!

Thanks, it’s been the most glorious thing. On top of that, just working on these projects have been great, from Artworxto to ALL CITY SHINE as a curator. Continuing to communicate, build with people, while taking the time for self-care has been so important. But I keep telling everyone that it’s the time to take it. You’ve been through all this all the time, it’s the time, there are no more excuses.

A good deal of your art reflects the Black experience and Black identity, which can often be informed by the climate we’re in. It makes me wonder how the period may have informed the rhythm of your work.

It definitely affected the work. The narratives around making sure there’s space for Black and people of colour has been a narrative well incorporated in my work since forever. One of my most recent personal projects revolves around my experience teaching at the TDSB. I’m trying to set up the next generation with brighter possibilities, futures, and better ways to see themselves individually. Though, it does have a darker tone, which I’ve titled Bad Dolls. It refers to The Doll Test from the 1940s which proved the ways a Black Doll would be seen as less educated, stupid, and bad by segregated Black children. My time as a teacher felt like a witness to that bias. The where it starts. It’s what makes my most recent art more focused on awareness, with children being the intention.

It isn’t unusual for a shadow to exist over my work. Similar to my work with the Toronto sign, what I often try to do is a form of alchemy. I take all that negativity and lift it. I always want to make sure we’re presented in a bold, brilliant, and beautiful way. Unapologetically us.

“We were kings, queens, and architects of a reality that’s present today. That’s the power of Afrofuturism. It’s in the illumination of these alternate realities that can be our actual reality.”

Continuing the talk of influences. How did this love of Afrofuturism influence you?

It goes back to the ’80s. As soon as I found out about the Flux Capacitor for time travel, I knew Afrofuturism was it. Combining a love of speculative fiction, sci-fi, and film anime into these bridged narratives, while also depicting Black and people of colour in my work felt natural. For me, Afrofuturism is a way of life. It’s an outlet for perspective. Time is a continuum, it’s not linear, and the ancestors are still with us, walking with us now. I kind of think of it as creating alternative realities in mass media because we’re always painted in this monolithic lens.

With Afrofuturism being this area of focus for you, what can that form of art mean to the current moment?

We’ve been seeing it more and more in our popular culture, Black Panther included. But the strength that Afrofuturism has isn’t limited to just depicting future images, but also the current present of Black weirdos, cool nerds, the diverse expressions from the Black LGBTQ+ community, and the multiple identities that can be shared. It’s funny, because the categories seem normal, but are different and outrageous to a general public that isn’t used to seeing Black people with a diverse sense of identity.

There’s also the power as a socio-political movement that Afrofuturism expresses. The narrative of slavery is the topic that’s pushed, but if you look back far enough, you’d know we weren’t always enslaved people. We didn’t yet experience this genocide. We were kings, queens, and architects of a reality that’s present today. That’s the power of Afrofuturism. It’s in the illumination of these alternate realities that can be our actual reality.

“The intent is to create a space for Black, Indigenous, Latin X, Asian, and BIPOC artists overall to do what already do. I feel when you’re given the space, you always come up with the greatest art.”

This might be a weird question to ask, but do you consider yourself a Black artist or just an artist?

Yeah, that’s the question. I have no problem with seeing myself as a Black artist or as simply an artist. It’s a conversation. I know people who’ve stopped doing Black History Month exhibitions because all of a sudden, they want every Black artist out there, but by March 1st the phone goes dry. I have no problem occupying the space though. It isn’t a quintessential part of my artistry alone, but it’s an important part. It’s always been about reflecting on my foundation and those of disenfranchised people for me. I always want to be in the position to paint us into the framework and make us know that we’re welcomed into these institutions, gallery settings, or in situations involving the Toronto sign. I love to see a child for example feel like they’re represented.

It’s something I was curious about. There’s this idea of not wanting to be limited to themes around Blackness among some artists I’ve spoken to, which is a reflection of the questions they’re asked. I wondered if it was something you thought about.

Yeah, I definitely thought about it during my career. Two things you said hit the nail on the head for me. I don’t feel limited by a label, but I also don’t need my work to say a particular thing. When you think of musicians like Outkast back in the day, being Black or a Black artist wasn’t an absolute limitation. I understand artists who don’t want the label. At the same time, I feel like whoever you are, or whatever your story is, all of that will come out in your work, directly or indirectly. It’s all good.

Tell me more about the ALL CITY SHINE exhibition. What are you bringing to the table?

We really wanted to bring together an all-star cast of street artists, graphic artists, and muralists to celebrate what they’ve contributed to Toronto and beyond in terms of street art and the pushing of new narratives. The intent is to create a space for Black, Indigenous, Latin X, Asian, and BIPOC artists overall to do what already do. I feel when you’re given the space, you always come up with the greatest art. More often than not, you’re limited to a certain theme outside of what you’d normally do. But for us, it’s about making sure these voices are heard as they do their thing.

This is obviously a massive collaboration of incredible talent. What sensibilities were you looking for when considering who you wanted to work with?

That’s a great question. We wanted a kind of creative excellence with everyone who participated. Each has their own story which they tell through their work. You can see their ethnicity and identity through the art and having an ensemble of diverse voices was important. We have artists who’ve been painting for 20-plus years in street and graffiti art. And we have artists who’ve been painting for 10 or 15 years with intentional acclaim attached to their voices.

I find that there’s sometimes a division between the various disciplines of art. By choice, I wanted to bring these masteries together and remove those barriers. During the past two years, I’ve found that people don’t actually care about these divisions, especially when talking about BIPOC artists. One project for example involved the painting of the Black Lives Matter mural in Kensington Market which involved 16 other artists. People came out with their own time and paint for the movement. There was a lot of love over the competition. It’s why with ALL CITY SHINE, it’s about shining a light back on us with the same glory we’ve shared with the city for over 20 years. I got a lot of love for our allies who’ve been super influential in allowing my personal work to happen.

You told me you’re a new father at the beginning of this chat. When you think about the way the world can impact one’s work, how is fatherhood impacting you and your career right now, even beyond the work?

It’s been a lot of glorious moments man. My wife and I experienced a lot of them daily, but also a ton of sleep deprivation. In terms of the work, it makes me want to create art with a more positive tone, as corny as that may sound. I want to paint a picture that my daughter can step into that’s healthy and optimistic kind of place. At the same time, we have to speak the truth on truth. Sometimes that’s ugly. I can imagine my child as a great artist someday, and by the time she grows up, she’ll be bored of that and maybe, she’ll want to be an astrophysicist. For me, it’s about trying to create a really open space for that.