Jeff Van Gundy might be the only person not tuning into The Last Dance.

Despite its effect on the rest of the basketball world, the hype for Sunday’s debut of the 10-part documentary series chronicling Michael Jordan’s final season with the Chicago Bulls has escaped the ESPN NBA analyst. But when you consider Van Gundy, a Knicks assistant coach before he took over the top job in 1996, was on the wrong end of many memorable Jordan performances that ended New York’s season in heartbreak, you understand why he wants no part of it.

“It’s like reliving a divorce,” says Van Gundy. “Who wants to relive a divorce?”

With basketball on an indefinite hiatus due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, ESPN answered the prayers of everyone besides Van Gundy and moved up the doc’s release date from June 2. During a time of the year when the NBA Playoffs should be in full swing, it's desperately needed. And in rabid anticipation of the debut episodes, we decided to resurrect one of our favorite forms of storytelling. Four years after we asked members of the media who covered Kobe Bryant to tell us their favorite stories about the Lakers legend, and two years after we did the same for LeBron James, we turned our attention to the original GOAT.

Van Gundy was one of our first calls, and while we appreciate his blunt honesty that he won’t be watching, we regret to inform you most of our hilarious conversation was off the record. But in the absence of a killer JVG story, we gathered plenty of poignant and comical MJ tales from highly respected current and former broadcasters and journalists who all witnessed different portions of Jordan’s time in Chicago.

What you’ll find below is a collection of memories, anecdotes, and stories that paint a tiny portrait of who Michael Jordan was—on the court, but, more interestingly, off it. All are personal, all are very different, and—most importantly—chances are you haven’t heard them before.

Steve Kerr is the coach of the Golden State Warriors, a former broadcaster at Turner, and was Jordan’s teammate from 1995-98. The fact that MJ had to make everything a competition, often involving money, sticks out most to Kerr.

“We used to have a contest. We’d shoot from the hash mark on the sideline. There were about four of us, maybe five of us. And at the end of shootaround, we’d start launching shots from there, and whoever made the shot first won. And Michael saw us doing it, and he just had to be involved. And so he came down and started getting into the contest every day, and before he knew it, it was for money. And he’d usually win it. That was sort of a typical Michael story. He just couldn’t—the competition. I think he loved the interaction with his teammates. Loved the whole idea of competing in any form. And it's kind of what made him who he was.”

Tony Gervino is the executive vice president, editor-in-chief at TIDAL and the former editor-in-chief of SLAM. Being on hand for MJ’s honest assessment of potential Jordan Brand endorsers during a meeting at Nike headquarters in 1997, Gervino was lucky enough to hear some epic Jordan shit-talking.

“While Michael Jordan was busy beating the crap out of the rest of the NBA, he also had a couple of side gigs: ensuring that thousands of adults involved with professional basketball were able to pay their bills, and, also, guaranteeing that millions of sneakerheads spent a good portion of that decade dead fucking broke. As someone who commuted between those two camps—probably spending more money on kicks than I made from launching the actual magazine KICKS—I understood the duality of Jordan’s appeal but was under no illusion: Be like Mike? Please. At no time and in no way did anyone think it was the shoes that made him, or would make us. They were just fire.

“The first time I met Michael Jordan was on the Nike campus in Beaverton in ’97, where my former SLAM co-conspirator Russ Bengtson attended an early Jordan Brand meeting. His extended team was kicking around names of potential endorsees in a freewheeling conversation, although I’m unclear as to whether No. 23 knew who we were or why we were there. See, Nike employees had a look: fit and healthy. I, on the other hand, resembled your college weed dealer, and Russ looked like EL-P’s derelict little brother.

“Over the course of an hour, we got to watch Jordan evaluate different NBA stars as either his kind of player or not. He pulled no punches, and his comments occasionally displayed that insane competitive streak. He favored productivity over flash but pushed back on a few suggestions of high-scoring Western Conference zombies, along with anyone with a difficult reputation. He was looking for killers, but not in the actual sense. As the conversation continued, he also offered some good-natured shit-talking about a couple of his own teammates, in biting commentary about every aspect of their lives.

“On the way home, we spoke about the gravity of the meeting, which made, sense given the pressure a player would feel representing not just Jordan’s brand, but also his name. And we agreed not to tell anyone about the shit-talking. That sounded like a plan until I put my hand into my jacket pocket on the flight home to discover that I’d lost the recorder, including the incriminating interview, somewhere in the Portland airport. It was not the last time that Michael Jordan made me, a devoted Knicks fan, literally sick to my stomach.”

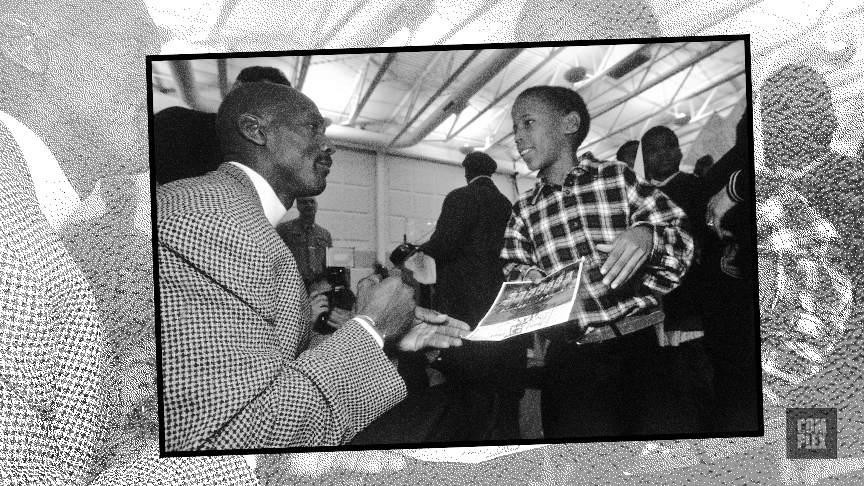

Cheryl Raye-Stout is a voice on WBEZ, Chicago Public Radio, and has covered sports in the Windy City, including the Bulls, since 1982. The night Jordan was brought to tears pre-game by a young fan is among Raye-Stout’s most memorable moments around MJ.

“When Michael Jordan was with the Bulls, especially the first run, and as he began his career, one of the things people don't realize is we had pre-game sessions with him almost every shootaround. We would have an open mic and Michael would be in there, and we were allowed to have any conversation with him, Q&As, his thoughts, and that doesn’t happen nowadays. One of the things that we got to see, again, because there wasn’t cameras in there at the time, is that there would be Make-A-Wish children that would come into that locker room, and Michael would sit with those.

“I’ll never forget this little girl. She was maybe about four, and he sat with her and just talked with her. We kept our distance to give them privacy, but we could see the exchange. When they finished, the little girl left, and Michael, tears just came down his face. It was really emotional to see. It was kind of private but not private. You know what I mean? That’s something that I won’t ever forget, because those sessions with Michael, like seeing that, us talking to him, that’s how I was able to break the story of him playing baseball and leaving the Bulls. So that’s why that’s more pertinent to me than almost anything that I dealt with. I mean, shoot, I got to sit at the table right underneath the basket. Michael would crash into it say, ‘Hey, how you doing, Cheryl?’ Stuff like that, you know. I think it was those poignant moments that was off the court which made it a different story for me.

“[Another time], we’re getting ready to go into the open locker room session to sit at the old stadium, and Rocket Ismail is pacing outside the locker room. He goes, ‘What do I say to him? What do I say to him,’ and ‘I’m going to meet Michael Jordan.’ I’m, of course, kind of looking and laughing. So we go in, the group goes in, and Rocket’s standing a little bit further away, and Michael goes—he gets up, he goes, ‘Hey, make as much money as you can.’ He was like, ‘Oh, he knew who I was.’”

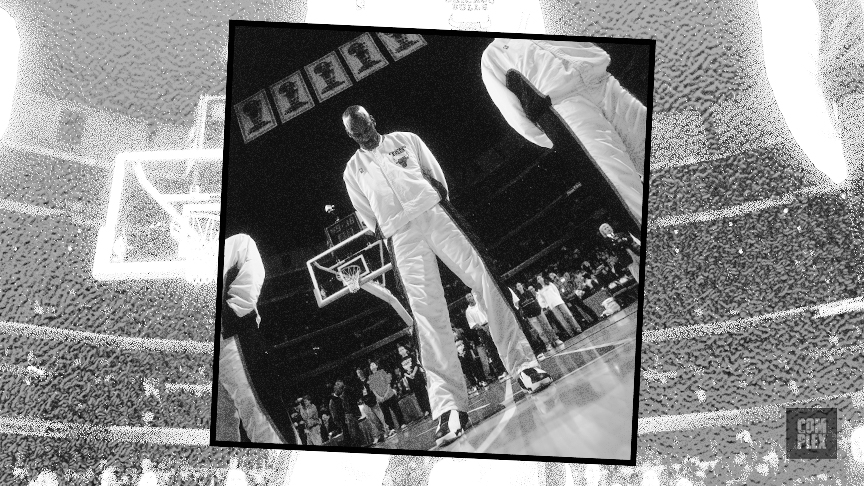

Kevin Harlan is one of the signature play-by-play broadcasters on the NBA on TNT’s weekly coverage of the Association. The voice of the Timberwolves from 1989-98, Harlan most vividly remembers how different Jordan moved on the court and his magnanimity off it.

“When he touched the ball, as a broadcaster, you were always prepared for something great: a score, a move, a defensive play. You were a little bit more heightened as a broadcaster every game I did Jordan that something different was going to happen. I felt that for Kobe [Bryant], too. When Jordan would take the ball up court and he would happen to be on your side of the court as a broadcaster, he was the only player that I ever noticed that it seemed like his feet never touched the floor. Like, his footwork and the way he moved, it wasn’t plodding. It wasn’t like you heard the foot hit the floor. It was kind of like he was floating. It was so weird. I could never in my mind figure out why it was like that with him only. He was the only guy who always drew a defender, it seemed like, at mid-court, but he would backpedal, moving sideways, cutting—it was like his feet never hit the floor. It was so strange. I would find myself later in my career looking at his feet and his footwork more than I watched his eyes or where he may have been wanting to go with the ball.

“Another quick thing about when I was with the Timberwolves and he was making a quick visit. Outside the Bulls locker room, in the hallway underneath the stands, there would always be this line of kids and parents and these Make-A-Wish Foundation groups. And their wish was to meet Michael Jordan before the game. And I would see this every time he came to Minneapolis—that line. It got the point where you could see down the hall and see the line of people, some with IV posts still by their side, some in wheelchairs, but it was always a mom and a dad, and they’re waiting to meet Michael Jordan. And I got to thinking, he’s here one night out of the year in Minneapolis. One game out of 82. And I said, ‘It’s gotta be like this everywhere he goes.’ Like, that was their wish—see, meet, get an autograph from Michael Jordan. You looked down the hall and saw that and it took you back. You caught your breath when you saw just what he meant and how important he was and what a big figure he was when you looked down the hall and saw these kids of varying ages and varying states of health waiting to get a handshake, a smile, an autograph, a picture, whatever it might have been. But Jordan, every night, I’m assuming, he faced that same kind of situation.”

Jackie MacMullan is a senior writer for ESPN and a recipient of the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame’s Curt Gowdy Award in 2010. In 1994, when Jordan took a year off from basketball and was toiling away as a minor leaguer with the Birmingham Barons, she went down to interview him for a story and knew he wouldn’t be playing baseball for long.

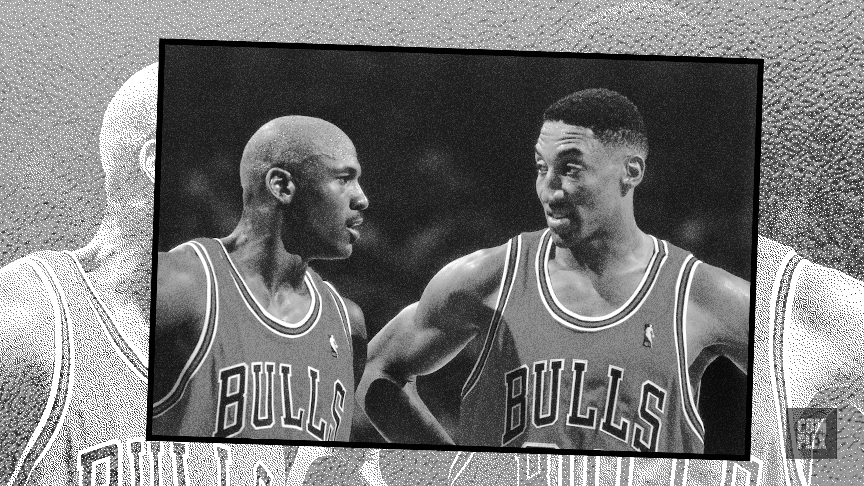

“It just so happened I went in May of 1994, and I was there, like, three days after Scottie [Pippen] wouldn’t go into the game in the Knicks series. So I think he knew I was coming—I’m not 100 percent sure, but I think he did—and Terry Francona was the manager, and, of course, I barely knew him then. I got there and was kind of looking for [Jordan], and I was sitting in the dugout, and the minute he saw me he made like a beeline for me, and the first thing he said was, ‘Do you believe this shit?’ And I was laughing because he was like, ‘This is what I don’t miss about the NBA.’ I was just incredulous, but then he started asking me, ‘What did Scottie say? What did Phil [Jackson] say? Why did he do this?’ The irony of Michael Jordan asking me what was going on with the Bulls wearing a baseball uniform was too incredible for me.

“During that interview—I was there for two days—he said, ‘I’m not going back. It got to the point where I wasn’t enjoying the game anymore.’ And he also said to me one of his biggest regrets was, ‘I couldn’t play hard for all 82 games. That’s when I knew it was time to stop.’ Yet I walked away from that whole experience thinking, ‘Nah, he misses it. I don’t care what he says, he misses it.’ And, of course, he came back.”

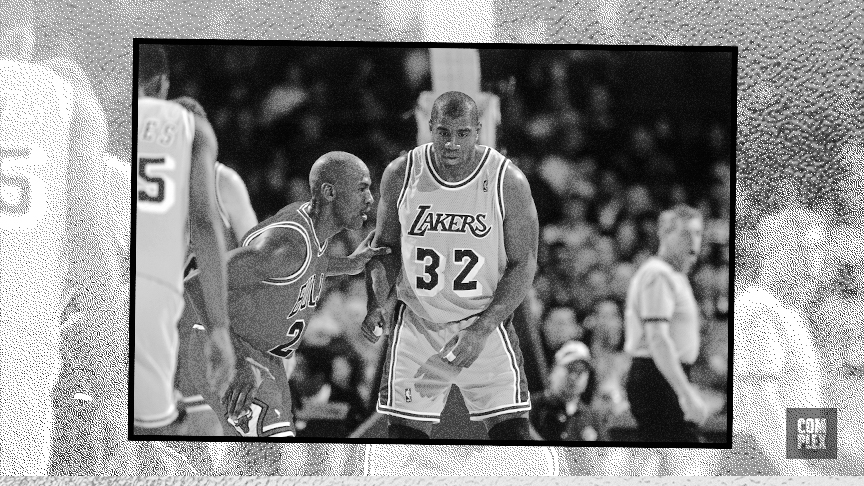

Marc Stein is a reporter for The New York Times and a recipient of the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame’s Curt Gowdy Award in 2019. Stein remembers the biggest single game he’s ever covered, when MJ faced off with Magic Johnson in Los Angeles.

“By the time I was covering the league, Michael had become more guarded with the media, so I never witnessed any of the great behind-the-scenes access from his first decade in the league to have the sort of stories Sam Smith, Peter Vecsey, or Jack McCallum could tell. But I will certainly never forget the night of Feb. 2, 1996. I was in my first season on the Laker beat for the Los Angeles Daily News. Magic Johnson had just come out of retirement and nearly posted a triple-double against Golden State in his first game back after almost five years away. He made it look so easy, but the second game of the Lakers’ brief Magic-as-a-sixth-man era came against the mighty Bulls, who were a tidy 40-3 en route to 72-10. I was calling him ‘Magic Mountain’ in print because Magic actually came back as a power forward and had to duel against Dennis Rodman. Michael and Scottie Pippen were determined to show Magic just how far away from title contention those exciting but young Lakers were—and I will remember it as the biggest single game that I had ever personally covered to that point in my career. In terms of regular-season games, after all these years, it still falls somewhere in the top five.”

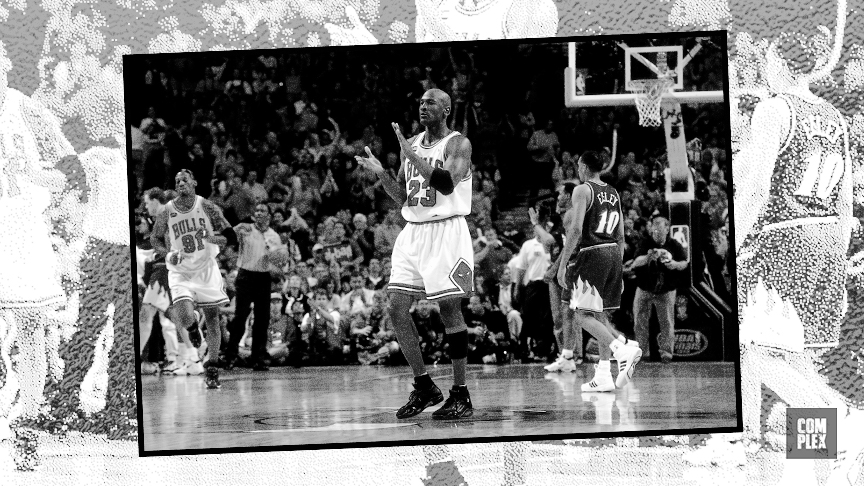

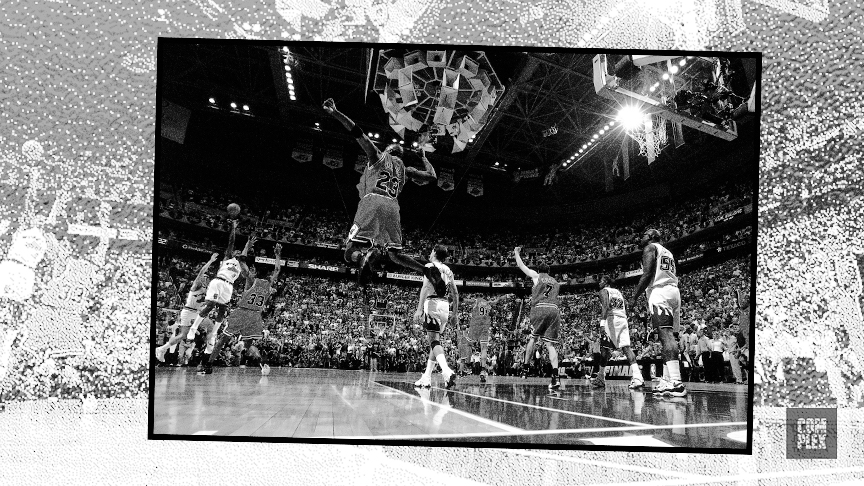

Skip Bayless is the co-star of the FS1 debate show Skip and Shannon: Undisputed. Before Bayless transitioned to the world of TV, he was an award-winning columnist at the Chicago Tribune, where he covered Jordan. He’s proud of his reverence for MJ, and the only piece of sports memorabilia he owns is a picture from Game 6 of the 1998 NBA Finals.

“I own one piece and only one piece of sports memorabilia. I bought a picture that was on sale after the 1998 NBA Finals in the gift shop of the Chicago Tribune, and it’s a black-and-white picture shot in Salt Lake City the night of Game 6, as it ended. It’s shot from the far baseline of Jordan’s last shot, where he’s holding the pose after a little subtle push-off of Bryon Russell. He’s holding the pose, the ball is swishing through the net, and you can see the horrified looks in the opposite baseline seats of all the Jazz fans who knew he had done it to them again. The beauty of the picture is Scottie Pippen is on the wing with his hands up like, ‘I’m open.’ He was unguarded at the wing at the 3-point line.

“It’s a beautiful picture, and it sums up everything Michael Jordan was and everything Scottie Pippen wasn’t to that team and that city. I knew the backdrop of it and how much it meant and what was riding on that shot. For 12 years in our New York City apartment, it was the picture, and every time I walked by, it inspired me. The beauty of it is the ball is in mid-net, and you can see a hundred fans, and you can see the cringes. You can see the pain starting to break out the faces of all the Jazz fans who knew he was doing it to them again. It’s the essence of him. But my favorite part of the picture is Scottie with both hands up like, ‘I’m open.’ If a picture is worth a thousand words, that’s worth a billion words.

“Tim Hallam, the PR director of the Bulls, had told me, or tipped me off before the game, that Scottie had come down with something and was going to tough it out and they were a little fearful that it would set in and that he wouldn’t be available for a potential Game 7. Michael had missed the last-second shot, which was a rarity, of Game 5 in Chicago. It was a shocking night to me because he missed it, and he came into the post-game interview room and he said, ‘That was cute.’ I said, ‘That was cute? That wasn’t cute to me.’ But it was almost like he set us up for, ‘Oh, watch what I’m going to do to them in their house.’ And, obviously, he winds up stealing the ball from Karl Malone in the corner, dribbling it himself all the way up the floor. Bryon Russell was a tough, physical, pretty fearless, savvy defender—[Jordan] did get away with just a little push-off, but that was the way the game was played. He ignores Scottie Pippen and basically says, ‘I got this. Watch this.’ And he holds the pose as it swishes. Scottie Pippen had scored two of his eight points on a dunk early in the game, and after the game I learned he had aggravated a back injury that had been plaguing him all year. So in that game, he had eight total points in 26 minutes. Jordan had 45 points in 44 minutes. Michael out-scored Scottie 45 to eight and out-scored the rest of his teammates 45 to 42. Clearly, he knew Scottie was ailing and he said, ‘I got this. I’m going to put this whole team and my whole city on my back, and I’m going to shoot a dagger into their hearts one more time with one more shot.’ I was so taken by the circumstance that he knows he might be without the guy I always called Tonto to his Lone Ranger. It was just so fitting that he ignores a wide-open Scottie, who, by the way, had shot no threes the entire game. He’s not going to let an ailing Tonto have that shot. Maybe LeBron [James], in today’s game, would’ve made the right play and passed to a wide-open teammate. I was so taken how [Jordan] rose above that moment and said, ‘I have to end this now because we might have trouble winning a Game 7. I got this and you don’t got this.’”

Mike Breen is the lead voice for the NBA on ESPN and ABC having called the past 14 NBA Finals. He remembers a few things about watching Jordan during his early broadcasting days, like how MJ would rip the heart out of Knicks fans and how he knew Jordan was going to put on a show before his legendary double-nickel game in 1995.

“As a kid growing up a huge Knicks fans and then becoming one of the announcers for the Knicks on the radio, as much as I respected Jordan during those stretches, I hated him because he was always knocking out my favorite team, the team I loved since I was a kid. The respect factor, the realization of the greatness [was there], but it was hard for me to like him because it seemed every season when the Knicks were, probably in a lot of cases the second best team in the NBA, he ended our season in misery. For me, it was a weird dynamic watching this great player, understanding he may be the greatest of all time, but at the same time I couldn’t like him because all he did was cause misery for my favorite team. He tore our hearts out every year. I think Knicks fans all feel the same way, the respect factor was there, but man o man, do you have to do it to us again?

“There were so many great playoff games, but the double-nickel game was a game that I’ll never forget. Because everybody was so excited for him to come back in and play again. I was actually looking forward to it because I wanted to see more of him because I was early in my broadcasting career. The Garden, to me, is still the most electric building in the world when it’s a big moment. And that was such a big moment and you knew from the opening tip that this was going to be something that he wanted to show everybody he was back. Although he scored a decent amount in his first few games when he came back, he didn’t really play that well. And the Garden always brought out the best of him. You could tell when he walked out on the court, even in warmups, he just had that look in his eye. He just destroyed them once again. We’re thinking, ‘Ok, he’s a little older, maybe he’s not as good, we can beat him.’ The irony of that last play where you know he wanted to score—I think he even said that his mindset going out on the last play was to score—but he winds up with the perfect pass to [Bill] Wennington. Here it is, the 55-point night, and the best play of the night was the pass because the Knicks doubled him.”

Jack McCallum is a former senior writer at Sports Illustrated, the recipient of Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame’s Curt Gowdy Award in 2005, and the author of the 2012 New York Times best-seller Dream Team. He remembers one crazy car ride with MJ after practice.

“I was in Chicago in the late ’80s to do a Jordan feature, and when he came out of practice, there were hundreds of fans around, and he didn’t have time to deal with them. So he told me to jump in his car and we’d do the interview there. As he sped through this parking lot in Deerfield, where the Bulls used to practice, he got waylaid twice when he had to stop the car. One time, a couple of would-be salesmen jumped out and showed him a Jordan sweatsuit they had designed. He smilingly took their card. He didn’t go but another block when he had to stop and a guy jumps out with a boombox and has a song he wrote for Jordan blasting. Jordan smilingly takes his card. ‘Is this what your life is like?’ I asked him. ‘All the time,’ he says. In journalism, you’re always looking to show, not tell. This was the Jordan story in its pure essence.”