Back in 1979, Jack Lambert, the fearsome, toothless middle linebacker of the famed Pittsburgh Steelers “Steel Curtain’’ defense, was asked what the NFL could do to ensure the safety of quarterbacks.

“Well, it might be a good idea to put dresses on all of them, that might help a little bit,” he said.

Lambert was upset about being flagged for a late hit on Cleveland Browns quarterback Brian Sipe.

Thirty-eight years later, Chargers linebacker Melvin Ingram was asked what he thought the NFL might look like in a decade or so. He told Complex this: “I think it’s going to be flag football in 10 years.’’

“If you watch football, if somebody gets hit hard, they’re going to throw a flag,’’ Ingram said. “They’re making it more of a soft sport. Football was always an aggressive contact sport and they’re trying to take that away from the game.’’

Ingram was upset about a $15,750 fine he was socked with five years earlier for a hit on Saints quarterback Drew Brees.

Athletes complaining that their sports are going soft is nothing new, especially from the athletes who make their living administering the hits rather than taking them.

But there is a relatively new entrant in the debate over whether pro football is, or should be, “going soft’’ in regards to better protecting its players—the overwhelming evidence that, even more than in boxing, brain injury, or Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, is an almost guaranteed aftereffect of a career in the National Football League.

A recent Boston University study of the brains of 111 former NFL players found evidence of CTE in 110 of them. And Thursday's news that Aaron Hernandez had severe CTE in his mid-20s once again brought concussions to the forefront of football discussions. Like the question of whether or not steroids improve the performance of Major League Baseball players, it is no longer a matter of debate. Playing football at the professional level causes brain damage. Period.

But there is another question to be pondered: Aside from the players, does anyone really care?

Although NFL TV ratings have been tanking the past few years, a trend that continued through Week 1 of the 2017 season, evidence shows that is attributable more to the changing viewing habits of millennials and younger viewers, many of whom are known to prefer watching non-traditional sports to mainstream sports and television programs.

There is little to no evidence that the NFL has lost any popularity due to squeamishness on the part of the public, or moral or ethical objections to watching a sport in which brain damage is an almost unavoidable by-product.

"There are always going to be some people willing to take the risks involved to get the advantages that athletic success can bring."

The fact is, people don’t seem to care if a large number of retired players show signs of early dementia, or if the autopsies of deceased NFLers reveal evidence of CTE in virtually all of their brains, or if a non-marquee player like Chris Borland, the 49ers linebacker who retired after one season in the league, decide that playing the game is no longer worth the risk.

The hard truth is, if a Tom Brady or a Peyton Manning showed signs of brain damage while still active, it might make a difference. The operative word being “might.’’

But the likelihood is the game would continue to thrive is because there are always going to be young men willing to risk their health and future for the chance of wealth and fame. And as long as economic conditions dictate that risk-taking can be lucrative, people who think it is their best—or sometimes only—alternative are going to play football, become professional boxers, or enter the military.

So the real question is not, “What can be done about it?’’ but “Where is it going?’’

The answer, most likely, is nowhere.

When repeated blows to the head are an integral part of any sport, there is a limit to how truly safe it can ever be. And when you factor in the size, speed, and strength of the modern player—these days, the average NFL lineman runs 310 pounds and the average defensive end around 285—you’re talking about a sport in which human torpedoes smash into one another with abandon hundreds of times per game.

And although helmet manufacturers are working to develop headgear that absorbs impact rather than transmitting it to the brain, and enlightened coaches are trying to teach their players the Seahawk, or rugby-style tackling that leads with the shoulder rather than the head, there is really little that can be done to eliminate the risk of the human brain sloshing around in the skull as a result of the collisions on a football field.

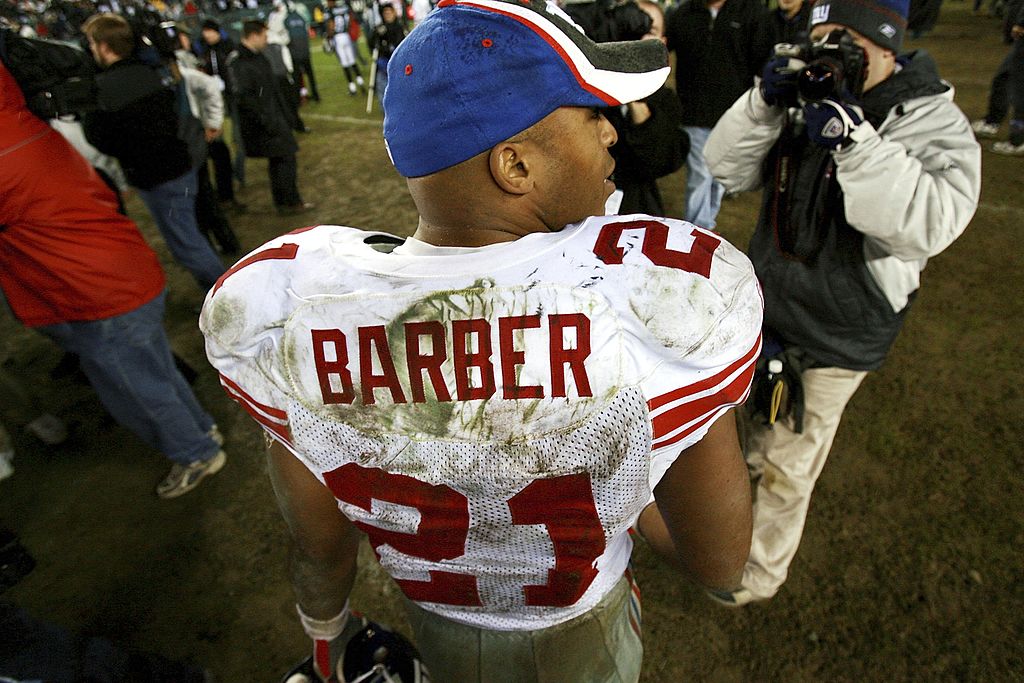

“I was taught to see what you hit, which basically means to put your face into the target,’’ says Tiki Barber, the three-time Pro Bowl running back who played 10 seasons for the New York Giants. “They’re trying to change that now but it’s a really hard philosophy to undo.’’

Although Barber missed only two games in his entire career because of injury, neither was due to a concussion. Which is not to say he was never concussed on the field.

“I probably had five in my career, but only two were serious,’’ he said. “And I only say that because I don’t remember them.’’

Barber says he has no qualms about his two sons, A.J. and Chason, playing football, but admits that had he known 20 years ago what he knows now about the effects of football on the human brain, he might have chosen a different path.

“When I was 19, I was a geek. I wanted to work for Microsoft or Oracle someday,’’ says Barber, who attended the University of Virginia on an academic scholarship and majored in business. “I was a marginal player on the football team and I certainly had another road if I wanted it. But there’s a lot of guys who don’t have that next best option. Those are the people who will keep the NFL alive.’’

"Nobody is going to give up driving, or texting while they drive, which is a lot more dangerous than playing football. I don’t

understand it."

While high schools in areas like East Hampton, Long Island, have dropped their football programs due to lack of enrollment, Terry Gambill, the head football coach of the Allen High School Eagles in Allen, Texas, says he has seen no dropoff in applicants.

“We get about 1,000 kids a year from the seventh-grade level on up," says Gambill, whose program has won 31 consecutive regular season games and plays in a 20,000-seat stadium that cost $60 million to build. “Football is way too important to the state of Texas for that to change. Friday nights mean so much to the community here. They bring everyone together. And the things the game teaches kids about life and discipline and teamwork and the value of hard work can’t be replaced by anything else.’’

Gambill said although he has incorporated Seahwawk tackling into his program to decrease the chance of head trauma, he believes the inherent dangers of football are greatly overstated.

“There’s somebody probably going to die of a car wreck tonight but nobody advocates the banning of automobiles,’’ he says. “Nobody is going to give up driving, or texting while they drive, which is a lot more dangerous than playing football. I don’t understand it.’’

Harold Barnwell, the athletic director at Miami Central High School, which has won five of the last seven state championships, agreed that parents in his area are not being scared off by the possibility of their kids suffering brain damage.

“It hasn’t affected our enrollment at all,’’ he says. “There are always going to be some people willing to take the risks involved to get the advantages that athletic success can bring. People here don’t seem all that concerned with the risks right now. They’re not looking down the road to what may happen later.’’

But he also agrees that playing football comes with unavoidable risk.

“You try to teach people the proper techniques, but even if you improve the helmet, when you get hit, that brain is still going to move,’’ he says.

The NFL has grudgingly accepted the verdict of medical professionals on the high risk of CTE and paid out millions in settlements. But it often seems the league is more concerned about improving performance than increasing safety; just last week it was announced that the league is spending millions to implant data-collecting microchips into its footballs to determine such vital information as whether the ball is traveling in a spiral or end-over-end.

And during a recent “Mom’s Clinic’’ designed to allay parents’ fears, Jane Skinner, the wife of NFL commissioner Roger Goodell, told a group of mothers, “Kids are more likely to get injured riding their bike on the way to (football) practice than at practice."

It seems that the future of the NFL can take one of two courses. One is the route that Jack Lambert thought it was fast-tracked to nearly a half-century ago and the one Melvin Ingram appears convinced it is on now—the road to non-violence and emasculation, ultimately becoming a sport only soccer moms and Gandhi could love.

Or, it could go in the opposite direction and become a modern-day version of the Roman Colosseum, in which the players take on the persona of gladiators, fully aware of the dangers they face but, unlike their ancient ancestors, not coerced but lured by the prospect of great wealth and fame.

Your guess on which of the two roads football will choose appears to depend very much on who you listen to, and which arguments resonate most strongly.

But in the end, it will probably come down to what everything in the United States seems to come down to—economic determinism, a fancy way of saying money talks.

“You might not see hits in communities where like 25 kids come out for the football program, but in places like Texas and Florida it’s never going away,” Barber says. “Those people love the game. The kids love it and their moms and dads love it. It’s part of their community. It’s akin to life.

“So that’s not going to change. But neither is this: When the body stops, the brain continues to move. And that’s always going to be a problem.”