Erin Narloch is always looking for sneakers. Bound by duty and maybe a bit of destiny, her search spills over from her professional life—where she is the senior manager of Reebok’s archive—to her personal life. She has dragged friends and loved ones into this pursuit during unrelated travels, into secondhand stores in different corners of the world.

“I have lost the attention of my family many times,” she admits of these excursions.

Conversation alone is enough to conjure the scents of the hunt, the stale air of a Goodwill in Wisconsin or the ripe charm of a vintage shop in Berlin. Narloch, an energetic Midwesterner fluent in sneaker history and deadpan, is after not just footwear, but anything Reebok related—apparel, ephemera, facsimile.

“Being in a Parisian thrift store and finding ripoff Reeboks from the ‘80s and ‘90s, when Reebok’s not even spelled correctly,” she says. “Those bootleg items—we have a whole selection of bootlegs.”

The Reebok archive at the brand’s Boston headquarters, which Narloch has run since she started at the company in 2016, is concerned with more than sneakers. It seeks to establish a complete portrait of the brand through time. This includes the things it has produced and the circumstances in which they were produced. It’s a grand image considering the long story of Reebok, which has gone through many forms since being founded in 1900 by Joseph Foster as J.W. Foster, a shoemaking business in Britain focused on track footwear. Narloch and her group seek to capture the metadata around Reebok items—the taglines, the commercials that introduced them, the reception by the public, their adoption by different groups of people. This fills in what she calls the viewing vacuum, turning the collected sportswear into something culturally rich.

“If you see an art object—let’s say it’s a reliquary—from medieval Europe, you’re looking at that object and judging it specifically for its physical appearance today. You’re so far removed from how it lived in culture,” says Narloch, who previously did archive work at Reebok parent company Adidas and spent over a decade employed at museums before that. “So that, to me, is what’s so critical about doing great brand work through the lens of history, is being able to contextualize that object.”

This endeavor can give a shoe more weight than it may have in the wild. Narloch sees herself as sort of a guide leading people into Reebok’s past. It’s a fitting analogy given the frontiers she’s crossed in search of shoes. She’s passionate about the job, even if it wasn’t in her plans.

“I could have never imagined this role when I was going to art school,” Narloch says, “or when I was working in museums and pursuing my masters.”

It is not her only role at Reebok, where she is also involved with the company’s relaunched human rights program. Narloch is eager to mention too that she does not run the archive alone. Her team includes Holly Roberge, Stephanie Schaff, and Maarten Warning, all of whom help with the acquisition and preservation of its vast contents.

Some of the sneakers in the archive come from eBay or garage sales. Some are donated by former employees, among them decorated design veterans. Most that do not come from the brand directly, Narloch says, are sourced via the internet. Others, like the extremely rare Chanel version of the Insta Pump Fury from 2000 done in all black, require more effort.

“I relentlessly hunted them down,” Narloch says of the previous owner of the unreleased and fabled Chanel Reebok, pausing to correct herself. “No, I researched and found and connected with them and had a conversation. And then we were able to acquire them.”

The intercontinental search—she remembers being in San Francisco while taking a call from Europe to secure the sneaker—adds to the lore and aura of certain archive entries. But the archive is not dictated, Narloch says, by her personal taste or experiences with them. Its wide swath is concerned with Reebok in every form.

The brand does not have a particularly linear story, and it has been sometimes protean, with tastes of different regions resulting in idiosyncrasies. In decades past, Italy’s Reebok looked different from America’s Reebok which looked different from Australia’s Reebok.

“Reebok as a brand didn’t create this global organization until 1990,” Narloch explains. “So when we had these really productive, incredible years in the 1980s, there are a lot of distributorships, a lot of individualization, within markets.”

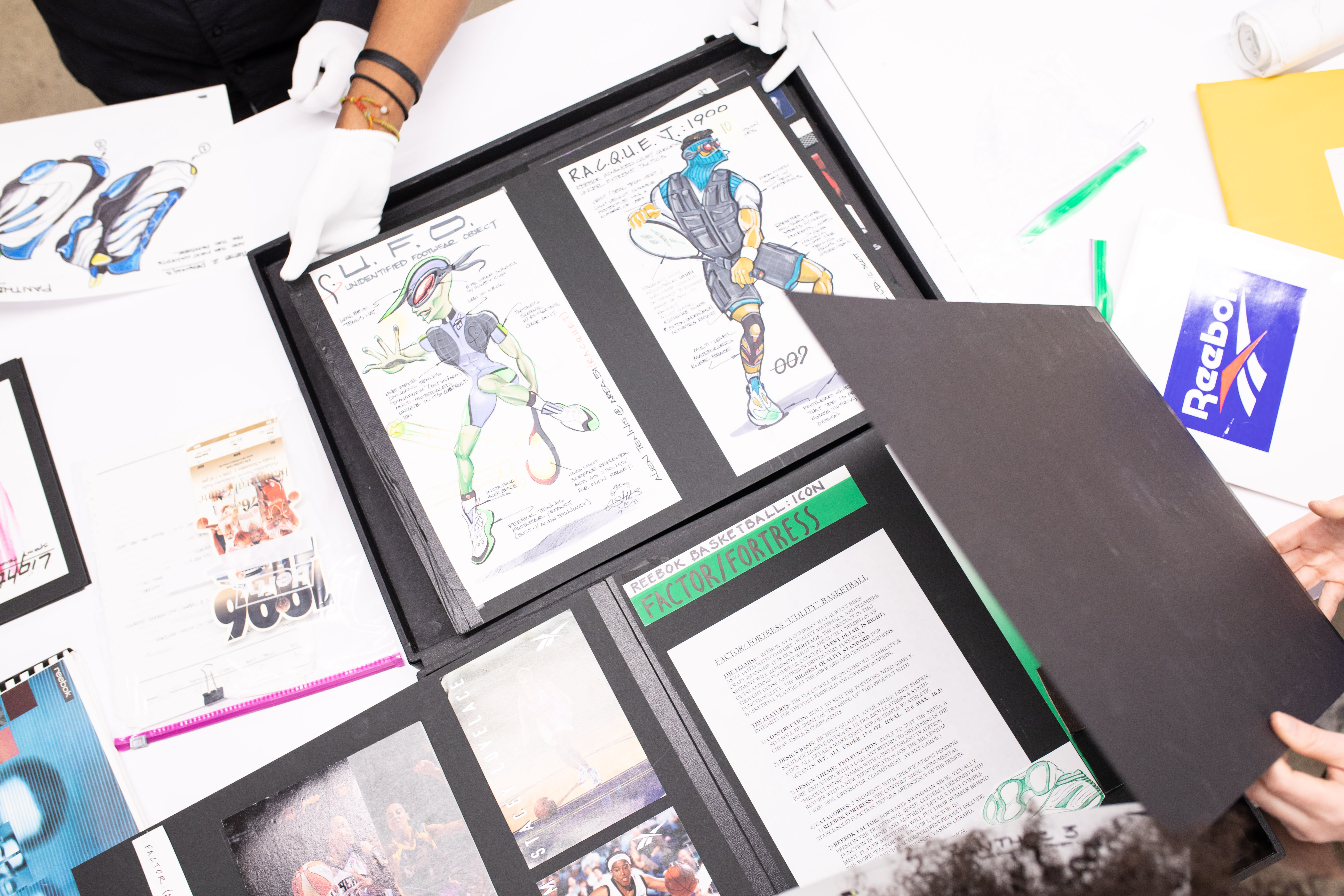

This complicated history is collated now at Reebok’s Boston HQ, where the archive lives. It consists of tens of thousands of items, from footwear to bags to advertisements to sketches to apparel. They are stored there in a wide room, where tall white shelves slide open to reveal rows of sneaker boxes and apparel tucked in Tyvek bags. There is a collections database with data surrounding the items: information about which factory they came from, which last they used, which designers were responsible for them, etc.

Not every single thing the company makes warrants inclusion, so there is some judgment made on individual significance. There is the mold for the original Pump shoe, an icon of 1980s sneaker tech. Reebok founder Foster’s desk is in the archive. There are sneakers worn in Eurovision and sneakers worn in the Olympics. Regrettably, the sneakers worn in Nickelodeon’s game show Double Dare, which Reebok sponsored during its run from the late ‘80s to early ‘90s, are missing.

“We definitely have reference to it in catalogs and different sell-in sheets,” Narloch says.

The archive has shoes that actually released, as well as prototypes that never made it to retail. Visitors are to handle them with white gloves. There is also a confirmation sample library, a collection of roughly 100,000 shoes, that features the final versions of sneakers that are OKed for production.

Most of these treasures spend most of their time at satellite storage facilities offsite, rather than at Reebok’s offices.

“With a brand like Reebok that does have this collective memory that stretches over 100 years,” Narloch says, “you want to have that accessible but safeguarded.”

Preserving sportswear relics is no easy task. There are delicate materials to be considered. The heel clip of an original black and silver Insta Pump Fury from 1991 may separate from its host, becoming brittle and breaking off. Glue will fade and soles will crumble. Reebok doesn’t try to restore these pieces but does slow down their deterioration and documents them via photograph before they expire. The ways they do this are relevant to any collector who has old shoes they want to protect.

“The boxes that you get your sneakers in, they are definitely not great to keep them in long term,” Narloch says. “Especially if there’s any acidity in that box, the off-gasses from cardboard and glue. You see it as evidence to older sneakers: the yellowing of glue or just the breaking down of all the different man-made materials.”

An ideal storage space should not fluctuate in temperature or humidity. (Some of Reebok’s archive pieces can’t be out in the open for too long for fear that changes in temperature will expedite their death.) Be wary of tucking them in a damp basement that could foster mold. Shoes should be kept out of direct sunlight, she advises, and in cooler rather than warmer temperatures. If one grows mold, it should be sequestered to stop the spread. What happens when a sneaker cannot be saved, though? Is there some ritual or rite of passage for shoes?

“No, we don’t have funerals,” Narloch says. “Yes, I mean, you can have a funeral. It’s called deaccessioning when you take something out of the collection.”

Though Narloch herself doesn’t hold funerals, her language around the archive suggests its contents were once living. The team will “bag and tag” pieces of shoes that fall off, like detached body parts in a morgue. The collections are animated by their contributors, who keep the pieces of rubber and plastic extant.

Paul Fireman, the onetime exec who made Reebok a juggernaut in the 1980s and eventually sold it to Adidas in 2005, visited the archive in the past year for the first time since the sale, donating materials from its first campaign after it went public. Steven Smith, a journeyman designer who’s currently a footwear director for Kanye West at Yeezy, has given pieces from the time he spent at Reebok in the ‘90s. E. Scott Morris, whose tenure there overlapped closely with Smith’s and whose portfolio includes signature shoes for athletes like Shaquille O’Neal and Emmitt Smith, has contributed greatly to the collections.

“Individuals whose lived experiences have been through sneakers” is how Narloch describes these people, who have given significant portions of their lives to the brand, then given work from that time over to the archive.

In Narloch’s view, they are the embodiment of Reebok. Their stories are the vitality of the archive, the substance that makes its contents emotive. Through them, the sneakers, some of them long extinct from factories or retail shelves, find life.