1.

By Reshma B

Since its release just over a week ago, Beyoncé’s Lemonade has been hailed as an incisive piece of social commentary touching on love, marriage, and infidelity, race, power and oppression, a testament to the strength and resilience of women.

Millions of fans have memorized the intensely personal lyrics. Countless critics have analyzed the album and accompanying film for hidden meanings, searching for clues about Beyoncé and her husband’s private life.

One of the things that makes Lemonade such a compelling experience is that listeners feel as if an intensely private superstar is putting her real business out there, on the record. We all know that Jay and B are a real husband and wife who go through their own issues as any marriage must. They are also a superstar power couple whose combined net worth has been estimated at over a billion dollars, so they obviously know a thing or two about playing the press and marketing music.

Still, when we see Beyoncé smashing cars with a baseball bat while singing about her man’s infidelity in the video for “Hold Up,” or when she calls out someone named “Becky with the good hair” at the end of “Sorry,” it’s hard not to wonder how real her sentiments are.

Immediately after Lemonade’s release, social media was set ablaze as members of Beyoncé’s BeyHive tried to figure out who Becky really was. As you probably know by now, the turmoil known as Beckygate dragged up speculations about Jay Z’s supposed affair with Rachel Roy, the ex-wife of his former business partner Damon Dash. Roy has been rumored to be the cause of the infamous elevator fight between Jay and Solange Knowles.

The cover art doesn’t even show Beyoncé’s face; we see only her hair—thick rows of braids woven tight, like armor.

You’ve read all about the incriminating IG posts, the tweets and counter-tweets, but chances are that the true identity of “Becky with the good hair” will never be revealed. (For the record, “Becky” is also a slang term for basic white girls—and for oral sex.) Arguably more important than identifying Becky, however, is understanding the true significance of the term “good hair.”

It’s hard to overstate the importance of hair within this visual album. The cover art doesn’t even show Beyoncé’s face; we see only her hair—thick rows of braids woven tight, like armor. In the opening moments of the film, she covers her locks with a hoodie. In the final shots, during the “Formation” video, her black hat obscures her features as two long braids hang down.

The film itself contains a vast collection of natural black hairstyles. Taking a closer listen to—and look at—Lemonade from this perspective, it becomes clear that one of the most important themes running throughout the album is hair: the huge emotional power and personal significance that hair holds for all women, and specifically for black women.

The psychological and social issues surrounding the idea of “good hair” are deeply rooted in the African-American experience. The term itself is a racially skewed value judgment handed down from slavery days implying that natural African-textured hair is “bad.”

4.

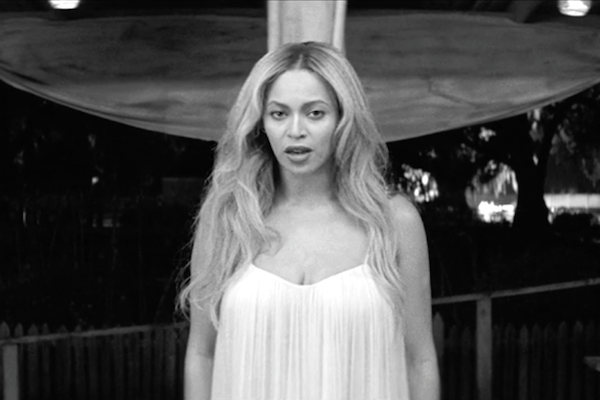

Screenshot via HBO

The disagreements between “good” hair proponents and those who reject the entire notion as a form of brainwashed self-hatred first entered popular culture in Spike Lee’s 1988 film School Daze. The unforgettable musical number “Good Hair and Bad Hair” depicted the conflict as a competition between the lighter-skinned straight-haired (and possibly weave-wearing) “Wannabes” and the nappy-headed “Jiggaboos” in an HBCU sorority battle royale staged at Madame Re-Re’s Beauty Salon.

So which team would Beyoncé have repped for? And would today’s Beyoncé be on the same team as she was back in the Destiny’s Child days? The R&B pop quartet’s debut album dropped the same year as The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill—that album’s lead single, “Doo Wop (That Thing)” found Hill tackling similar subject matter:

It’s silly when girls sell their souls because it’s in

Look at where you be in, hair weaves like Europeans

Fake nails done by Koreans

Come again

Although Beyoncé has been known to wear straight hair, the lyrics to “Formation”—the first single off Lemonade—announced a new attitude:

“My daddy Alabama, Momma Louisiana / You mix that negro with that Creole make a Texas bama / I like my baby heir with baby hair and Afros / I like my negro nose with Jackson Five nostrils.”

The “baby heir” in question would surely be Blue Ivy, heir to the Knowles-Carter empire. Blue Ivy’s hair is an adorably unruly mop of curls, just the way her mother prefers it. (Blue’s parents have rightfully ignored the change.org petition that circulated begging them to comb their daughter’s hair.)

Premiered just hours before the Super Bowl halftime show, “Formation” freaked a lot of people out. Beyoncé’s dancers wore their hair in Afros with berets perched on top, in a nod to the Black Panthers. Fox News pundits quickly denounced Bey’s new song as “divisive.” Several police unions—including the singer’s hometown of Houston—have even protested the Formation World Tour.

In an interview with Elle magazine, Beyoncé responded to critics of the song who charged that it was “anti-police,” quickly shooting down the claim. “If celebrating my roots and culture during Black History Month made anyone uncomfortable, those feelings were there long before a video and long before me,” she said. “I’m proud of what we created and I’m proud to be a part of a conversation that is pushing things forward in a positive way.”

6.

That conversation got pushed a whole lot more when Lemonade dropped on April 23. Used in the context of Lemonade, “good hair” is a term of derision. It could be seen as a double put down: Beyoncé’s not just dissing Becky, she’s expressing disgust that her black husband would be so fascinated with that type of girl.

Malcolm X’s Autobiography devotes a whole chapter to the subject of hair. “My First Conk” details the author’s recipe for homemade relaxing cream before he comes to the realization that “I had joined the multitude of Negro men and women in America who are so brainwashed into believing that the black people are ‘inferior’—and white people ‘superior’—that they will even violate and mutilate their own God-created bodies to try to look ‘pretty’ by white standards.”

He describes black men with “conks” and black women with “green and pink and purple and red and platinum-blonde wigs” as “more ridiculous than a slapstick comedy” and raises the question whether “the Negro has completely lost his sense of identity.” He also points out that he sees the conk on “all too many Negro entertainers.”

Throughout America’s Civil Rights era, hairstyles like the Afro became a rebellious political statement, defiantly rebuking the notion that African-Americans should mimic straight, smooth European hairstyles as a way of conforming to societal “norms.” Other natural styles from cornrows to dreadlocks to straight-up nappy heads took the hair rebellion to another level.

In Chris Rock’s 2009 documentary Good Hair, the comedian went on a search to find out what makes hair “good.” Amongst the celebrities interviewed in the film is video vixen Melyssa Ford, who wastes no time beating around the bush: “What I looked at as ‘good hair’ is… white hair.”

Dr. Maya Angelou offers a contrasting view. “It’s not a good thing or a bad thing—it’s hair,” the late poet says later in the film, adding with a laugh, “If you have it on your head it’s good. If it’s growing between your toes it probably isn’t so good.”

But Dr. Angelou understands that hair is no joking matter. “Hair is a woman’s glory,” she asserts. “You share that glory with your family. They get to see you braiding it, they get to see you washing it—it’s a glory!”

No wonder, then, that the black hair business is a multi-million dollar industry that sells tons of chemical relaxers, wigs, and weaves to women who desire “good hair.” This industry prizes specific types of “virgin” (untreated) human hair, particularly Indian hair, for its rich, natural look. (Being of mixed Indian and European descent, chances are that Rachel Roy probably does have what many would consider “good” hair.)

Good Hair reveals the lengths to which black women will go in order to keep their hair looking this way, from using the “creamy crack”—a slang term for powerful sodium hydroxide hair “relaxing” creams—to paying extortionate prices for wigs and weaves. Actress/comedian Raven-Symoné admits to spending tens of thousands of dollars to maintain her own weave, calling the expenditures “an investment.”

8.

Screenshot via HBO

So where do all these hair weaves come from? Good Hair traces much of them back to India, where bags and bags of human hair are collected daily to be sold in the West. In India, hair is considered a vanity and removing it is an act of self sacrifice. Many Hindu women shave their heads as a way of giving thanks to the gods. These cuttings are gathered and sold at a huge profit by Indian entrepreneurs.

But the demand for human hair is so great that even the temples cannot fully satisfy it. Some Indian girls have been known to wake up to find their hair has been cut off while they slept. Thieves have been known to creep up from behind and cut off an unsuspecting girl’s ponytail while she watches a movie. Although illegal, this practice is not taken very seriously by Indian authorities. “It’s a small crime to cut and steal hair,” says one man interviewed in Rock’s film. “It’s only hair.”

During one of my trips to Jamaica, another place where hair extensions and weaves are a hot commodity, I was interviewing Notnice—the producer of many hit songs for dancehall artists like Vybz Kartel, Alkaline, and Popcaan—when he told me that he could get a lot of money by selling my hair. (I have Indian heritage from my mother’s side.) If he was joking, he didn’t laugh or smile, but I brushed the comment off and left the studio with my hair intact.

“The reason why hair is important is our self esteem is wrapped up in it,” said Sheila Bridges, an interior designer who suffers from alopecia, an autoimmune disorder that causes baldness. “It’s like a type of currency for us even if those standards are unrealistic and unattainable—especially for black women.”

One of the rawest moments in the film version of Lemonade is a chilling line of verse from the chapter “Anger,” penned by British-Somali poet Warsan Shire: “If it’s what you truly want… I can wear her skin over mine. Her hair over mine. Her hands as gloves. Her teeth as confetti. Her scalp, a cap. Her sternum my bedazzled cane. We can pose for a photograph, all three of us. Immortalized… you and your perfect girl.”

The idea of putting another girl’s hair on your head—especially your romantic rival’s—is one of the most potent images in Lemonade. But in a way, lots of Beyoncé fans do that every day. You can walk into a weave shop in any city, or log onto one of several websites, and purchase a “Beyoncé style” weave to put on your own head.

10.

Screenshot via HBO

While Beyoncé is known for all aspects of her style, those flowing locks are an important part of her image. So when she cut a large part of her hair off in 2013, fans went crazy. Many saw her super-short haircut as a feminist statement against society’s gender roles.

“I got a little teary eyed!” Beyoncé’s long-time stylist Kim Kimble told People magazine at the time. “I’ve been working for her so long, she has this beautiful long hair and it’s hard to grow hair out. I feel like it’s my hair, I work so much with her. I feel a little emotional but excited for her too. Maybe I’ll cut my hair off now,” she exclaimed.

Kimble, who owns Kimble Hair Studio in Los Angeles, is credited as the main hairstylist on the film version of Lemonade. Among the nine other hairstylists (not to mention 15 assistant hairstylists) credited in the film is Neal Farinah, who created the long braids look in the “Formation” video. Although he was on the road for Beyoncé’s Formation World Tour, the master stylist—who runs his own salon in Fort Greene, Brooklyn—hopped on the phone to give his perspective on the art of styling a superstar’s hair.

“Yes, it is crazy,” Neal said during the second day of the tour. “It’s very mentally challenging. This is my seventh tour with Beyoncé—I’ve done every one of her tours—and I’m proud to be here again!

“I’ve worked with Beyoncé almost 10 years. I have many iconic moments with her, a great many trendsetting hairstyles that many women love and that have inspired many hairstylists. I’m thankful that I still have that privilege today.

“When I’m not working on tour I have clients who support me. Some have been coming to me for 20 years now. I love going home to the salon. It keeps me grounded and humble. I always like to go back to my salon and work with any woman that walks into my door. I love women because without women I would not be who I am today. They are the ones who sit in my chair… every week.

“Hair is like the number one part of a woman. For the majority of women hair plays a very important part of their femininity. Some women are insecure when it comes to losing their hair. That’s one of the reasons why I will be coming out with my own hair line this fall.”

12.

Screenshot via HBO

Neal does not subscribe to the idea that there is any one type of “good” hair. For him, it’s all good. “I am an artist and I went to school to do all types of hair,” he says. “I’m not going to say I’m good for one texture here and one texture there—no. I can do any hair. There’s so many hair textures: Caucasian, Asian textures, African-American, Latino, mixed hair. Each texture is totally different, and of course there’s different ways of approaching each texture.”

Nor does Neal look down on people who wear extensions, wigs, and weaves. “It’s all about creation and perfection,” he explains. “I want women to embrace anything they wear, whether it’s a weave, extension, a wig. If that makes a woman confident, beautiful, and happy, I support her. Any woman that wears anything in their hair that empowers them.”

Neal says he’s had many clients ask him to make their hair look like Beyoncé’s. “You know that’s just a normal thing,” he says. “I meet many women on the street and they say, ‘Oh my gosh! You inspire me to look like Beyoncé.’ But it’s not about Beyoncé. Everyone who sits on my chair, it’s my job to give them 100 percent plus. I want that woman on my chair to feel very happy, very confident, and very beautiful when she walks out.”

As for sharing any secrets of B’s looks, forget about it. “Whatever me and Beyoncé do, that’s our personal business,” says Neal. “Of course that’s always going to be the question. No, I’m never going to say ‘Hey, that’s what we did, what we didn’t do…’ I just do my great work with her and try to inspire people and leave it as it is.”

Although the details of Beyoncé’s hair secrets remain closely guarded, it seems unlikely that she could try out so many different looks without some sort of extra assist from hair pieces, which can be a source of insecurity for many women. “I’m not too perfect to ever feel this worthless,” she sings on “Hold Up.” Imagine Beyoncé, one half of a billion-dollar couple, feeling worthless.

Near the end of Lemonade, Beyoncé pays tribute to her grandmother Hattie, who inspired the title of her album. “I was served lemons but I made lemonade,” she remarks at her 90th birthday celebration. “My grandma said nothing real can be threatened,” B adds later. Does that principle apply to hair as well? Maybe it does.

One thing’s for sure though: Beyoncé Giselle Knowles surely doesn’t mind all the talk, as long as it’s about her. The last two lines of Lemonade drive that point home:

“You know you that bitch when you cause all that conversation / Always stay gracious, your best revenge is your paper.”