Four years ago, Kanye West rewrote the definition of an “album” in the streaming era. Or so we thought.

Historically, artists and record labels treated the album as a static collection of tracks that were complete upon release. Albums would be delivered to consumers via physical formats like vinyl LPs, cassettes, and CDs, the contents of which were fundamentally unchangeable. Even if an artist or label did want to modify an album, it would be a marketing and logistical nightmare: They would have to issue entirely new physical copies to reflect the change, then make sure that new version got out to all the fans who wanted to hear it.

Streaming hypothetically throws this nightmare out the window. Artists no longer need to commit to manufacturing tens of thousands of physical records upfront and hope that they all sell. After all, in a streaming environment, songs and albums are fundamentally just a combination of 0s and 1s that algorithms analyze and spit out as sound, to fans who pay a monthly subscription for access. Not only is the concept of “inventory” irrelevant in this world of infinite shelf space, but the cost of experimentation and modification around artwork, track order, track content, and other features of digital releases also plunges dramatically as a result.

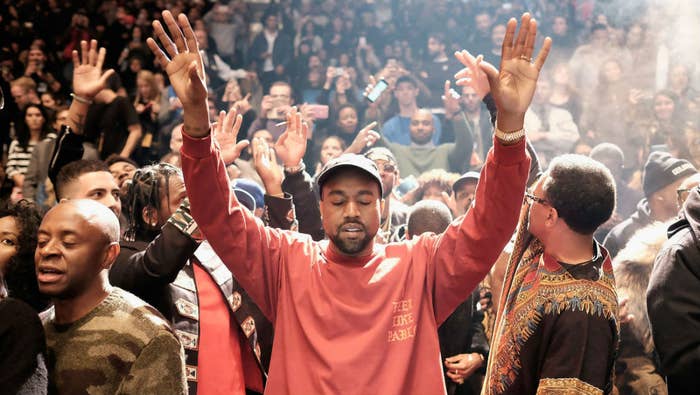

West was the first celebrity to take advantage of this new, fluid technological landscape with The Life of Pablo, which first came out on Valentine’s Day in 2016, but ultimately had multiple versions released to the public. The rapper first premiered a nine-track version of the album four years ago today (February 11, 2016) at his Madison Square Garden fashion show, then made a different, 18-track version available for sale briefly on Tidal with slightly modified lyrics—before taking it down and making a separate “partial version” available to stream as a Tidal exclusive. By the time TLOP was made available on Spotify, Apple Music, and other streaming services nearly two months later, there were yet more changes, most notably some new celebrity features on “Wolves” (which were leaked a few weeks prior anyway).

The music media went wild in reaction to this tumult. Fortune, TechCrunch, NME, and The Los Angeles Times all suggested that, in openly tweaking TLOP, West was turning the album into “software.” Most recently, in October 2019, Axios revisited The Life of Pablo as a case study for how streaming platforms have “made music mutable,” and how “the ability to instantaneously edit music after its release could be used in ways we can't expect in the future.”

Yet, despite this media chatter and fan frenzy, virtually no artists have followed suit in creating a truly dynamic album with content updated over time on streaming platforms. Instead, it’s mostly the same old process as artists opt to release a static album, no modification needed or planned.

This isn’t an issue of technology; it’s an issue of culture. For many artists, albums are long form manifestos that take months, or even years, to craft in a way that accurately reflects their own creative vision. Under this approach, releasing an album is almost like birthing a child: The process is intensely personal and cannot be rushed, and there’s a collective sigh of relief, awe and/or wonder among the artist, the fans, and the wider public once the album is alive in the wild.

In contrast, for artists to treat albums the same way West treated TLOP, they have to be okay with albums existing as perpetual works-in-progress that are appealing because of their unfixed nature. They have to be okay with releasing album “updates” often—monthly, or even weekly—rather than waiting several months or years to feed new content to fans, even if they feel that the update isn’t “ready enough” yet.

None

One could make the argument that this software-driven approach to album releases is ultimately better for the music industry as a whole. After all, major labels are throwing millions of dollars a year into marketing budgets for a wide range of albums, with success far from guaranteed. Embracing a software mindset would allow labels and artists to mitigate some of that risk by not spending all the marketing dollars around a single release, but rather by spreading out marketing over multiple release “versions,” gathering valuable fan feedback along the way. What is there to lose?

West’s approach to rolling out TLOP closely mirrors two specific concepts from the tech and software industries that clash with conventional music culture.

The first concept is versioning—which normally refers to the creation and management of multiple releases of a given tech product over time, each of which is more improved, upgraded or customized than the previous release. For instance each new Apple operating system is a more updated version of the previous one, as of early February, Twitter’s iOS app is currently on Version 8.7.1, and cloud-based collaboration platforms like Google Docs and Github feature revision histories, showing which collaborators made which changes to a given document or project.

The terminology of versioning doesn’t come up often in the world of music. Artists and producers do send different versions of tracks to their collaborators regularly behind the scenes, using cloud-based platforms like Dropbox, WeTransfer, Byta, and Splice. But versioning albums in public, and issuing software-like updates to existing releases, is much rarer.

The second concept is prototyping. In the worlds of tech and design, a prototype is an early, bare-bones draft version of a product—called a minimum viable product (MVP)—built with the purpose of testing a given concept with a small set of users. For example, it’s typical for streaming services like Spotify to test new features like social playlisting with select power users before releasing those features to the wider public.

Prototyping a product or feature before its official release is both normal and encouraged in the tech industry, as it allows developers to validate (or invalidate) their ideas quickly and get feedback on what is and isn't working, thereby reducing the risk of failure.

Importantly, effective prototyping also comprises a mindset, not just a process. In the book Sprint, veteran technologists and designers Jake Knapp, John Zeratsky, and Braden Kowitz outline the prototyping mindset that helped companies like Blue Bottle Coffee, Slack, and Gimlet develop culture-changing products.

In the authors’ words, to embrace a prototyping mindset is to switch your satisfaction level “from perfect to just enough, from long-term quality to temporary simulation.” Moreover, prototypes are meant to be disposable. “Don’t prototype anything you aren’t willing to throw away,” write the authors, as “the solution might not work.”

Finally, by spending any longer than one day on a prototype, developers risk becoming too emotionally attached to the outcome of the test. “The longer you spend working on something—whether it’s a prototype or a real product—the more attached you’ll become, and the less likely you’ll be to take negative test results to heart,” write the authors. “After one day, you’re receptive to feedback. After three months, you’re committed.”

The way West approached TLOP’s release was a mix of versioning and prototyping. One could call the Madison Square Garden premiere TLOP 1.0, the partial Tidal exclusive TLOP 2.0 and the final wide release TLOP 3.0, each version building and improving on the previous one (the notion of improvement in the case of art, of course, is subjective).

And while West may have planned all these sporadic changes to TLOP ahead of time, he was also likely embracing a prototype mindset. He released the album to a limited number of users on Tidal before it was truly “ready,” monitored the media’s reactions and collected user feedback, then updated the album with new “features” that he thought would be suitable for a wider listener base.

In fact, TLOP is one of the first albums that R. Michael Hendrix—a Partner & Global Design Director at IDEO and Assistant Professor at Berklee College of Music—discusses in his Berklee course The Creative Entrepreneur Mindset, as an example of applying design principles to music production.

In Hendrix’s eyes, incumbent music-industry practices are far behind what technology allows us to do today. “It’s interesting because some people look at what Kanye did with TLOP and think, somewhat superficially, that he doesn’t know what he’s doing or that he’s too impulsive or excitable,” Hendrix tells me. “But on the other side, the fact is that the traditional systems built to promote music and gauge its success don’t match his behavior. If you start thinking about a song or album as a piece of digital art, the idea of having multiple different versions of it is totally normal. It only feels abnormal if you’re judging it based on an old, 20th-century system that we largely don’t abide by anymore.”

Public prototyping does already happen in the music industry in a few different ways. DJs regularly test out new, unreleased songs during their sets to gauge reactions from the dance floor. Remixes and acoustic versions of songs are a socially-accepted way for artists to test out and expand into new market segments. Tools like ReverbNation’s Crowd Review and Amazon’s Mechanical Turk help crowdsource private feedback on songs at scale. Even seeding music into TikTok memes can be a useful prototyping tool, to study the types of content that everyday users want to create around a given earworm or chorus in an unreleased single.

But again, there’s a fundamental conflict in mindsets between the typical software designer and the typical independent musician. “In the product world, with prototyping you’re trying to understand a market need, and then meet that need through iteration,” says Hendrix. “In contrast, with music, you’re not necessarily trying to meet anyone else’s need. You’re trying to please yourself as an artist, and to communicate a distinct emotional statement coming from the heart.”

None

This emotional element underscores another reason why a lot of musicians may be uncomfortable treating their albums as prototypes. They would subsequently have to treat these songs as disposable and changeable, instead of cherished and immutable. Understandably, there’s still a stigma around releasing an early version of a song or album before it’s 100% "ready," in the case that it doesn’t resonate properly with audiences. Hence why “leaks”—a phenomenon that’s largely a relic of the heyday of physical formats and MP3 files at the turn of the millennium—still feel so out of place for many major artists in a streaming-first world (hello, Lady Gaga).

“It’s not even so much about music ‘leaking’ anymore, because in a streaming era, leaks won’t make you lose that much money. Rather, it’s about controlling the narrative,” Marc Brown, founder of Byta, a private music-sharing platform for industry professionals, tells me. “Why did Beyoncé drop her 2013 album without any warning? Because she wanted to control the narrative. This is even more important for smaller artists who, unlike Beyoncé, don’t have that level of control. They need to build confidence and make an impact with fans, and with the music industry. If their art is out before it’s ready, they won’t succeed at articulating the vision that they wanted.”

Nonetheless there are still lots of creative ways to release unfinished prototypes of your work while still maintaining creative and narrative control. For instance, hip-hop producer Kato on the Track—who has worked with the likes of Denzel Curry, Tory Lanez and Dumbfoundead—periodically posts previews of his unreleased tracks on Instagram, asking followers to tag which rappers or fellow producers would sound best atop the beat.

However, even Kato admits that approach is not for everyone. “The key question is, are you putting the same level of creativity into presenting your unreleased beats as you are into your music that’s already out?” Kato tells me. “Most people aren’t going to Instagram to listen to beats. If you’re an artist who doesn’t have a lot of attention yet, and you’re just posting your unreleased beats with a static image that doesn’t engage people, they’re going to skip to the next post because it’s not interesting to them.”

This is perhaps what feels like the most radical takeaway from TLOP, even today: that there’s value in the unfinished. In fact, in TLOP’s wake, there’s potential for a musical niche to develop parallel to non finito—an aesthetic approach in painting and sculpture that leaves an artwork intentionally looking “unfinished.” In this scenario, the creative process becomes the product more than its output, and the state of being unfinished creates more demand than the finish line itself. It would reinvent the purpose of recorded music as we know it today. Whether that’s something today’s musicians and fans actually want, though, is a different question entirely.