Once upon a time, in a land not-so-far away, being too dripped out was a crime. Seriously. In her new book, Fashion Killa: How Hip-Hop Revolutionized High Fashion, journalist Sowmya Krishnamurthy revisits an English parliament law that dictated what people of certain social strata could and couldn’t wear. In the 14th century, you couldn’t rock the color purple or a “cloth of gold” unless you were a knight or a lord. Imagine spending a day in jail because you were a broke boy with the nerve to cop some purple Amiri.

In 21st-century America, those literal laws aren’t in effect, but fashion—what folks wear, how they wear it, the economic infrastructure that determines what’s chic and what isn’t—remains an immutable sign of power. In her debut book, Krishnamurthy examines its interactions with hip-hop, from Dapper Dan to Pharrell Williams. Inspired by her own experiences as a rap fan who’d stare at elegant Vibe magazine covers, Krishnamurthy explores the many layers of a relationship that’s been characterized by underappreciation, explosive trends, unsung icons, and a lack of access. At the intersection of class, race, and economics, she sees designer drip as a stylish tool of upheaval.

“In many ways, fashion can be a form of rebellion,” says Krishnamurthy, who spent three years putting the book together. “It's like saying that ‘I'm not supposed to be wearing this, and there's a history of people who look like me who weren't allowed to dress in a way that was considered successful or acceptable by whiteness. And I'm kind of throwing up the middle finger.’”

The rebellion has been multilayered, with rap-fashion innovators struggling to penetrate the world of haute couture, even as they cultivated sartorial art for folks in urban communities. It’s a dense history, so Krishnamurthy set out to make it accessible with Fashion Killa, which was titled after ASAP Rocky’s 2013 single of the same name.

In conversation with Complex, Krishnamurthy speaks on her new book, a comprehensive debut that distills the history of fashion into a digestible package.

Toward the very beginning of your book, you explore the history of fashion laws. Why was it important to jump into that so early?

One big question I had in the beginning of the book is why do people wear luxury? So this idea of wanting to wear clothing that's considered nice or expensive or somehow aspirational, where does that come from? I knew I wanted to tackle the psychology. I inherently understood the social signaling. You wear Gucci or Louis Vuitton and you leave your house, and people know that you can afford Gucci or Louis Vuitton. So it sort of shows your stature in life, and we all know that old quote: Dress for the job you want, not the job you have—that kind of fake it till you make it. I also understood the idea of people wearing certain clothes that maybe they weren't at that economic echelon yet, but they wanted to showcase. It was sort of manifesting it into being.

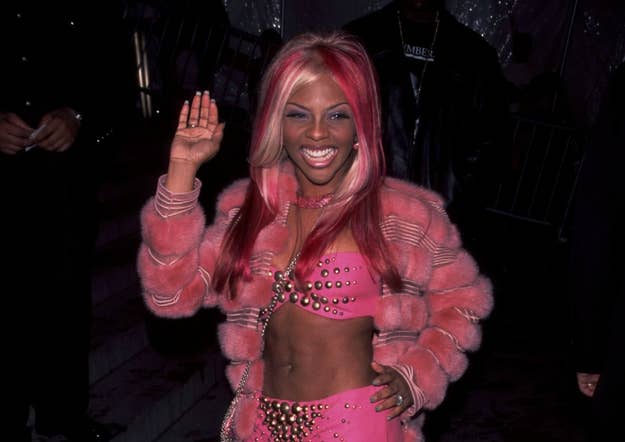

"I don't think [Lil' Kim's] gotten the industry accolades that I think she deserves. And that's the thing: Fashion and hip-hop are very reflective of the world we live in, and oftentimes women are just considered secondary characters."

As I was doing the research, I really got into this idea of when we talk about history, there is a legality component. Even going back to the ancient world, looking at something like ancient Rome, certain colors like purple were really affiliated with something like royalty. So again, this idea of luxury isn't just name brands or a price tag. It can be as simple as a specific color once you get into America from the time of the early settlers and later on. It was even things like fabrics—who could wear what kind of fabrics. And in America, specifically, because of the history with slavery and racism being so inbuilt into the DNA of this country, those rules and laws were also ways to really create barriers and showcase who was allowed to wear certain things.

Who is the most underrated hip-hop contributor to fashion?

Well, as an artist, of course, Lil’ Kim. This is someone who, from the beginning of her career, embraced luxury. She's name-checking things like DKNY in her songs and wearing minks and furs, very much embodying this mafioso boss. And very early on, she really embraced this idea of being a risk taker and a trendsetter. So whether it be the colorful wigs and furs in the “Crush on You” video, her infamous VMAs outfit where her breast was exposed—that's a creation from Misa Hylton—to later befriending and becoming a muse to people like Donatella Versace, Marc Jacobs, David LaChapelle, people like that. What's so interesting is we take a look back and look at everything she did, and it's almost shocking that she never got the cover of American Vogue. She was never honored by the CFDA awards. The industry of high fashion did not really embrace her in this way that one would expect.

Now, there is a lot of talk behind the scenes with people who feel like she should get those things, like a CFDA Lifetime award or something to that effect. So I would definitely give her the nod as an artist. But when it comes to designers, I have to also give props to April Walker. She's someone who, with her Walker Wear brand, came up around Karl Kani, Cross Colours. And as a young female designer, she was working with people like Tupac and Biggie at very much of the start of their career. For one reason or another—I think a lot of it has to do with sexism—she hasn't gotten the same amplification that I think her male contemporaries have gotten. Slowly, those things are changing, and I do see her getting a bit more exposure now, but she was really a streetwear originator.

Along those same lines, even someone like Kimora Lee Simmons. Baby Phat is often relegated as a quote unquote “urban fashion line” or the “sister line to Phat Farm.” But in reality, she too was a streetwear originator. This was someone who, because of her long lineage as an actual supermodel from the time she was, I believe, about 13 or 14 years old, she knew about high fashion. She was the muse of Karl Lagerfeld. She knew how clothes fit on a woman's body, and she leveraged her space in hip-hop to create one of the most exciting hip-hop fashion lines. So that's kind of another name that, although the line was commercially successful, I don't think she's gotten the industry accolades that I think she deserves. And that's the thing: Fashion and hip-hop are very reflective of the world we live in, and oftentimes women are just considered secondary characters. It's funny, even if sometimes the clothes are meant for women, the designers or the people in decision making are men. So I think when it comes to these unsung heroes, oftentimes they're definitely women.

Why do you think rap brands have failed to receive the high-fashion connotations of a Fendi or Louis Vuitton?

That's a great question. I think a lot of it just has to do with the zeitgeist and hip-hop. So let's go back to the late ’90s and using Sean John and Rocawear as the case studies. They really were birthed from two extremely stylish, but very entrepreneurial minds. So Puffy at this point already has success with Bad Boy Records. And in the case of Rocawear, what happened was Jay-Z wanted to work with Iceberg, which at the time was like the Gucci of hip-hop. There was nothing cooler than Iceberg. And they turned him down. When I interviewed Dame Dash, he said, “I took that personally, and I'm going to make my own line because you won't work with us.”

That DIY ethos was very much within hip-hop at the time. As we're getting to the late ’90s, early ‘00s as an industry, it's exploding. We see so many young people as entrepreneurs, they have their own imprints, and that was just the spirit of the time. Let's fast-forward. Now most artists want to sign to a major label. We don't see a lot of those powerhouse imprints anymore. When it comes to starting your own line, it's a lot of work and it's also really expensive. I spoke to Dao-Yi Chow, who worked for Sean John and then later launched his own Public School line, and he said that it's a huge financial undertaking, and it's a lot of work.

"I would love in the future to see artists actually leveraging their power and influence to create something of their own, because to me, that's what really sparks institutional change."

I think for most artists now, would you rather do all of that, possibly lose money, or would you rather partner with someone who's established[and] you know the brand's going to sell? And even if it doesn't, it doesn't matter because it's not your money on the line. You're going to get your check either way as a collaborator or modeling as the face of the brand. So the risk is much lower. I would love in the future to see artists actually leveraging their power and influence to create something of their own, because to me, that's what really sparks institutional change. For whatever it's worth, Kanye created arguably the most successful hip-hop fashion brand. And Yeezy not just took over hip-hop fashion, but you would look at the high-fashion runways, and everyone was copying what he was doing. He was really creating those trends. And that's something where I think he realized, “I'm incredibly powerful. Why am I outsourcing that or giving that away to other people when I can just kind of keep it for myself?”

Besides Kanye, why hasn’t any rapper really stepped up to launch a major clothing line and stay with it?

I don't know. I think one thing about fashion or any sort of extension for an artist—I truly believe you have to love it. And there has to be passion and interest and commitment and curiosity. Those are the lines that succeed. Puffy loves fashion. He’s been fly since he was a baby. You look at baby pictures of little Puff and he just looks amazing, right? That's that Harlem fly. You look at someone like Dame. Dame's also from Harlem, and for him, this idea of Roc-A-Fella, it was about aspiration. It's about this idea that we are really getting money and we want to show the rest of the industry that you need to catch up to us. We're on boats; we're in St. Thomas. We might drink Cristal, and then when we stop drinking it, you're going to want to drink what we drink.

It was really about this lifestyle of the rich and famous for Kanye; from day one, he loved fashion. This was the guy, the Louis Vuitton Don—everyone knew his penchant for Ralph Lauren and wearing those pink polos. But even early, talking to people who know him, they say he talked about wanting to do a line. This is before he became a household name, before he had the means to do it. It was really important to him. So I think for an artist to get into this space in a meaningful way, there's got to be that passion. There's got to be a commitment to it beyond just that quick check. Because starting any type of entrepreneurial venture, you're not going to see that quick money. It's kind of this longer-term vision. So I would say for an artist to think through that lens, don't view it as just, I'm doing it because everyone else is doing it, or it's trendy. It's something you actually care about.

Right, that makes sense. Can’t fake the passion.

One thing that's harder now, too, is social media has made it such that it's also hard to differentiate oneself. Before every artist had their own style, and different regions had their own signature. You would see an artist from New York, and they might have Timbs or they're wearing Air Force Ones, which they call Uptowns. Then you go over to L.A. and it's all about flannel; it's about the Nike Cortezes, khakis, bandanas. Go to the South—they had grills. Everyone had a little bit of that distinction. Now with social media, everyone kind of looks the same, and it's really hard. How do you find a brand that everyone else doesn't know about? Or how do you find the one stylist who's your secret weapon, and they're pulling from places nobody knows about? That becomes difficult in the age of social media. How do you truly differentiate yourself as a fashionista? How do you create the trends versus just jumping on them?

All that said, which rapper do you think has the most potential as an impactful designer?

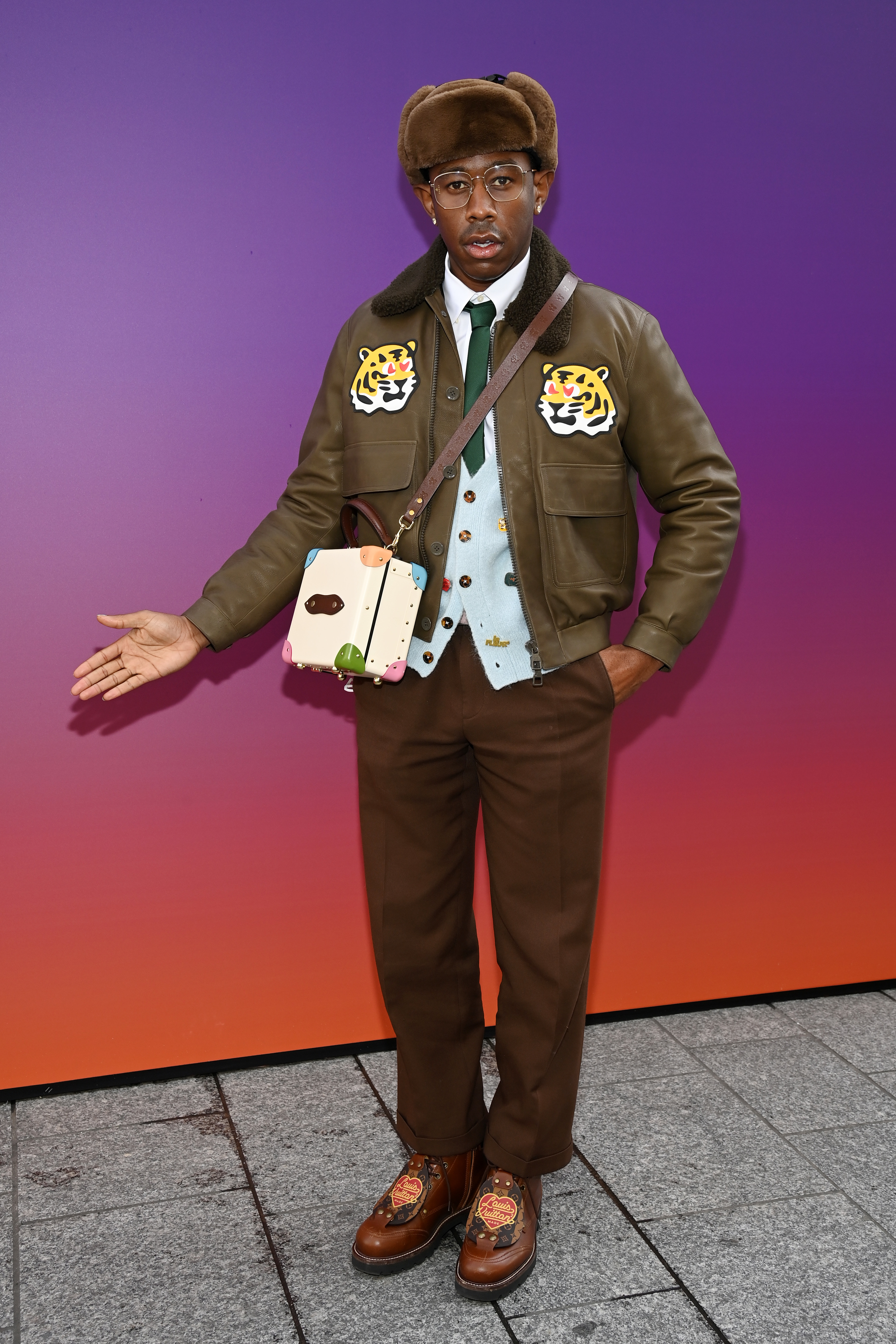

Maybe someone like Travis Scott. I'm thinking of someone who's that next-generation, great sense of style. His fans really do follow his moves when it comes to what he's wearing. I could see him maybe doing a capsule collection, and perhaps that then turns into something. With so many of the younger artists, I would argue that their version of the rapper clothing line is merch. You had mentioned Golf Wang prior. Same for whether it be Dreamville, whether it be OVO, it's just now merch. So the fans are wearing it sort of with the same vigor that they wore some of the previous iterations of rap-fashion lines; it’s just called something else. You just go to a concert or you go to their website and buy it. But it's kind of that same spirit. I think Ye still has the crown. I don't think anyone's coming for it, but I think Travis is possible. People always ask me what rapper's closet I would covet. I love how Pusha dresses. I think his style is incredible, and he's just someone who's able to evolve while still being true to himself. I think he would do something really dope as a capsule collection.

And even with a Cardi B, it's interesting. She has worked with some fast-fashion lines before, and I think that's really smart for her fans, but she's very much a haute couture darling as well. So it would be interesting if she does try to do something in that more luxury space. What would that look like? I don't know. But I do really like the fact that she does work with newer designers and she's able to amplify them as well. So I could see her being really smart and putting together a cool team of creatives to put something out there—I think specifically for women. That would be interesting.

It was really cool to see how Dapper Dan comes into play at the beginning of your book and how he surfaces again at the end. It’s really a great full-circle moment.

Dan is such a great figure because his story really ended in many ways with that raid—I believe it was in ‘92 with Fendi, and then doesn't pick up until much later. We're talking decades later, and now he's extremely celebrated by high fashion. He's getting all the accolades that prior he just never got from the industry. So it does show this very much full circle. But what I also love about Dap is he is someone who has stayed true to himself. His atelier’s in Harlem. He said, when he wanted to work with Gucci, “We can work together, but you have to have a footprint in Harlem. That's important.” And I love that he's able to leverage his power and his position in a way that gives back to his community.

I think that's really special. And I also just love this idea that in his mind, to find the next Dapper Dan, you have to go out on the streets. That's where this next visionary is coming from. And it leaves that door open. We've seen the 50 years of hip-hop this year, but who knows what the future holds? Is it going to be an artist being the face of the next great American heritage brand? Will we see more artists following Pharrell's footsteps and try to take on roles at existing brands such as the Louis Vuittons of the world, or is it going to be something totally different, like the kid who's making sweatshirts or printing T-shirts outside of their mom's basement and just makes a ton of money doing that? So there's so many ways and directions that this story can take, and I wanted to leave it with that open-endedness as well, because culture is a continuum. It's constantly moving and shaping and growing, and although the book sort of ends with a period, the story continues.