If you have ever put on a club night or live event, whether it’s three of your mates playing to the rest of your mates in the back room of a pub, or a hot-ticket event at a massive club or venue with international acts and punters from across the country, you’ll be acutely aware that it can be fun, even if it is a bit of a hassle. And even if you’re a seasoned pro like Jamie Jones—co-ordinating and negotiating everyone’s schedules, making sure the line-up makes sense even if you have to change course and opt for plan B—it can be a lot.

This year, however, Jones has had to do that for the better part of a year—with the tireless help of his management team, it has to be said—to pull off filling an entire Ibiza residency line-up that has boasted sets from Skream, Richy Ahmed, Hot Since 82, Skepta, and, frankly, too many more to list here, but it’s enough to take him right through until the first week of October. He also has an album on the way and if you’ve been tracking the build-up, you’ll have noticed that while the singles we’ve had—“Lose My Mind” (featuring vocals from Connie Constance) and “Got Time For Me” with Channel Tres—are still very much dancefloor-focused, both tracks are more vocal-led and built as much for the headphones as the bassbins.

Of course, this is far from Jones’ first foray into that territory. His supergroup, Hot Natured, with Lee Foss, Ali Love and Luca Cazal (plus regularly contributing vocalist Anabel Englund), was a huge success in the indie/dance crossover days, but within the purist house music community, it proved controversial and the backlash from his peers was brutal enough to make him shelve the project, at least for a time. Things have moved on considerably, though, and as he promises more vocal moments on his impending album, there’s also talk, however tentative, of the supergroup’s return—but all in good time.

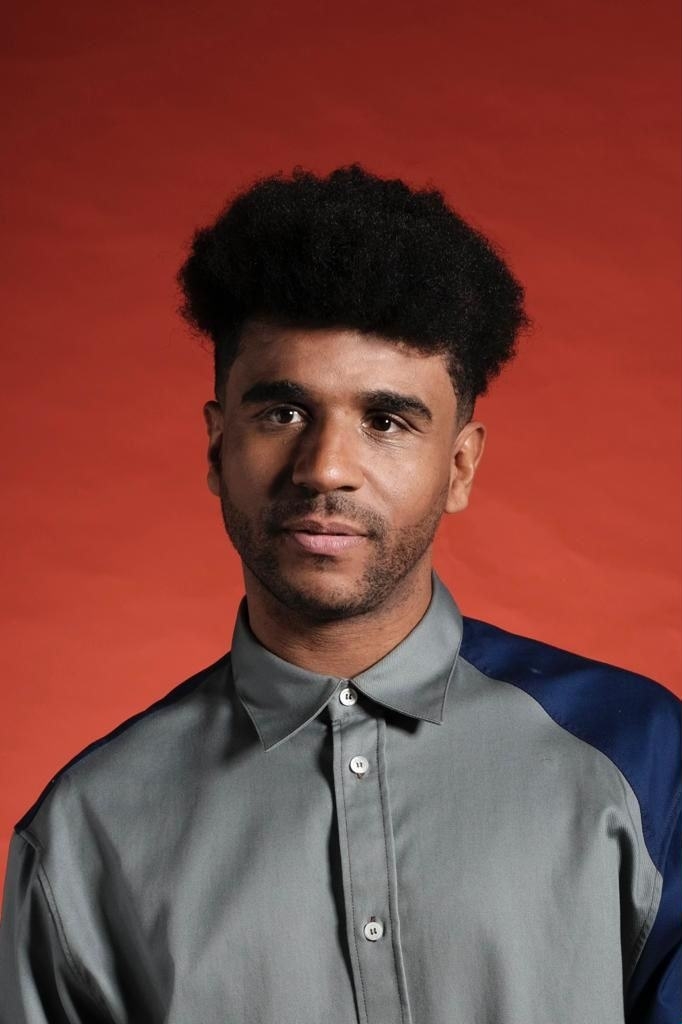

We caught up with Jamie Jones in a brief moment of calm to discuss his ongoing Ibiza residency, the relationship between cities, structure and sound, and the happy hardcore that first captured his imagination in North Wales.

“I’m big on preparation... I think that you can never be nervous as long as you’re well prepared.”

View this video on YouTube

COMPLEX: Okay, let’s start with the line-up for your Paradise residency at Amnesia in Ibiza: how do you go about putting something like that together? Because it’s at least half a year, right?

Jamie Jones: Yeah, it’s definitely a long process. It pretty much starts at the end of the season before, in October, when we start reaching out to people. It’s also a very complicated thing, because there are a lot of nights on the island. People have their own things, trying to work out who can play what dates, and there’s a lot of politics that goes on. People don’t understand. It’s like moving chess pieces around to see who can do what where, and making little deals with people to swap to play for them instead. Not just for me, but for other artists as well, our residents. It’s this whole huge puzzle.

Sounds like a lot.

We pretty much start off with working out who are the main guests that we want, based on who we know is going to rock the night, that’s going to bring the right vibe and also try to be as different as we can each season, which is not easy because DJs that smash it in London or New York don’t always necessarily work in Ibiza. It’s also about trying to find something new, as well as maintaining relationships with people and keeping some consistency with what we’re doing and helping to build new relationships over time with people that we really love booking. There are lots of things to consider, but it’s pretty much myself, my event manager, Nick Yates, and my manager, Jazz Spinder, and we just go back and forth for many months and work things out.

You mentioned that certain artists work in certain cities and maybe perhaps not as well in Ibiza. Historically, certain cities have almost been defined particular styles of music. Is that still the case?

They do, definitely. It’s less so than when I started touring a long time ago, the best part of 20 years ago. Before YouTube and Spotify and all these kind of things, you would go to different places and the sound would be very different. You would notice that stuff that was really current in Berlin or in London was just really too upfront for a remote place in Australia or something, but now that’s changed a lot. Obviously, everybody has pretty much the same access to everything online, but it’s less about that than it used to be. As a DJ travelling around the world, I’ve found that every place has its own energy and its own groove. A set that works for me in the UK doesn’t work as well when I play in Italy because people dance differently, they have a different history when it comes to electronic music, what they’ve grown up with, what DJs, what events, what popular music is; all of these things go into what creates people’s rhythm.

In the UK, for example, we have a history of drum & bass and garage and all this kind of multicultural sort of music that’s informed what people feel on the dancefloor. Then, in somewhere like Italy, it’s much more based on rhythms and a continuous vibe rather than moments. I think Ibiza is the same. It has the Balearic spirit. People are on holiday and they’re there for a week or two and they’re having this intense experience. Because Ibiza is an intense place; you can have the best of times and the worst of times here, but usually the best of times. If I think about what I want to listen to at 5.00am on a dancefloor in Ibiza compared to what I want to listen to at 5am in a warehouse in Berlin, it’s not the same at all.

So how do you balance that with your own identity as a DJ? How do you balance what people are expecting from Jamie Jones: the DJ and, for example, what they’re expecting from LA: the place? Which takes precedent?

That’s a good question for me because there are many different types of DJ. Some people are very specific in what they do and they’re fantastic at it. And it doesn’t really go much outside of that. In some ways, people really appreciate that because you know what you’re getting and you love that and you go and see it and you know what you’re getting. I’m more like one of those DJs who’s always been into different things. I’ve had different moments in my career. Originally, when I first came on the scene, minimal techno was big: Richie Hawtin, Villalobos and those guys. That’s what was happening in Ibiza; Cocoon was a big night there and everyone was influenced by that. I was sort of in that scene in a way, although I had a bit more of a housey flavour and that became more of a disco, deep house thing when I started Hot Creations and Hot Natured and stuff like that in the early 2000s and 2010s, and then more tech-house.

It’s actually something I really have had to work out how to do and not to go in too many different directions when I’m playing sets somewhere that I don’t know. Places I know well and play often, I know what works there for me. If it’s Miami, if it’s in big venues in the UK, big festivals like Parklife or Creamfields or even Glastonbury, I know what crowd comes to see me there. I played pretty much every Glastonbury for 12 years and the same with those other festivals. But when I go to somewhere new, I tend to do a bit of research beforehand into who the other DJs are, who normally gets booked there. Is this more of a techno club or is this more of a house club? If you’re playing for more than two hours, you can sort of feel things out and go from there, but if you’ve got a short set in a festival in a country you’ve never been before, sometimes I need to sort of do a little bit of preparation. I’m big on preparation, personally. I think that you can never be nervous as long as you’re well prepared.

Love that. I read somewhere that one of your first loves as a teenager was happy hardcore. Have you ever been tempted to dip back into that world at all?

[Laughs] Absolutely not! Listen, when you’re 14, it’s great. It’s funny because I’m still into taking pop samples and putting a harder edge to them, but the harder edge that I put to them nowadays is nowhere near DJ Dougal and what those guys were doing. When you’re young, it’s really fun and energetic and your energy levels are there for that. But for me, that was a time and a place.

How did you transition from that to more traditional house music?

I used to walk around my village and my town with a Sony Walkman, listening to Fantazia and all these Helter Skelter mixtapes. And then I always used to get this magazine called Eternity. There was Eternity and Dream, which were monthly rave magazines. They’d go to all these big raves and take pictures of clubbers and sell all the merch and stuff, and there’d be interviews with the DJs in the mag. On the back page, there was always an ad for turntables. It was like a DJ starter pack. I didn’t even know the difference between belt drive and direct drive turntables then, but I managed to convince my mum to get me a set for Christmas. This was in ‘94/‘95, so I was about 14 or 15 and then I got those but I had no clue how to use them. There was no YouTube to show you. Luckily, on Pete Tong’s show that I listened to every Friday—because that was the only radio station I could get in North Wales and Snowdonia—Carl Cox had a little segment on there… This is the long version of the story, by the way.

Crack on.

Anyway, Carl Cox had a little segment on there that basically said: this is how you mix two records together. You take the first beat and count it in, then you push it in and use the pitch control to match the beat. I was so amazed by that because I didn’t know! It sounds silly not to know what to do, but I just was like, “What am I doing?” Anyway, from then on, as I was hooked. But just before that, as soon as I’d got the turntables, the first two records I bought were two hardcore records that I’d had somebody playing on a mixtape, and this was before I even knew how to use the decks. I went to the record store and I bought Kim English’s “Nite Life”, the Masters At Work remixes. And then I bought, like, three or four house records and then that was it. I was into U.S. house music from then on. It was literally a switch from happy hardcore to Masters At Work. There were no in-between bits.

View this video on YouTube

Then you moved from Wales to East London. How did you first get set up? Did you already know people in London when you moved there?

No. When I first moved to London, I was staying over in Ealing, West London, in a houseshare and my housemate was in a band. I ended up hanging out with all his mates and they were all indie kids, so we’d go out to more indie-ish things. Occasionally, I’d drag them out to a couple of things in London, but that was the first time, maybe one of the only times in my life where I’ve been a bit lonely because I really wanted to go out to some raves, but I didn’t really know anyone. That was tough, but then that summer, after my first year in uni, I did a season in Ibiza and met people who are still some of my best friends today. Dionne Estabrook, who works for my management company, she’s been working with me for 10-plus years now. I met her that summer. And then the following year, I moved to Shoreditch. But yeah, the first year was tough, but then when I went to Ibiza, that’s where I met my lifelong friends who live in London.

You mentioned there have been quite a few eras and you’ve explored quite a few different sounds over the years. You have an album on the way with tracks like “Got Time For Me” with Channel Tres, which really stands out as a vocal-led song. Can we expect more of this kind of thing from the album?

Yeah. So I started working on an album very loosely at the tail end of the pandemic. One of the things that I always tried to do years ago, before electronic music was as big as it is now, was to bring things that I was passionate about to as many people as possible. That seems obvious, but at the time, there was only one or two big electronic festivals in the UK. It was still quite a niche thing in a way, and people really valued the underground and crossing over was almost like a dirty word back then. Now it’s huge. This was before David Guetta did a track with Rihanna and all these kinds of things, but I always wanted to do something like that. I think that’s why I went on that path with Hot Natured 10 years ago, but to be honest, it scared me a little bit when we did it back then. A lot of people thought that we were bringing the wrong kind of people into the house scene. At the time, I was much younger and when you first experience a backlash of hate, it’s quite traumatic.

You have this thing you’ve been so passionate about for so many years, you’re always the up-and-coming person, people are rooting for you, and then all of a sudden, there’s a bunch of new people who like you for just these hit songs. Meanwhile, there are these people that you thought you respected saying that this is commercial music now, even though it was way more underground. A lot of stuff has crossed over into the charts now, but it was a different time and it was before this melding of underground and overground that’s been going on for several years. It’s difficult because I’m a natural-born raver, so I love that, but I don’t necessarily want to listen to banging club records at home. I just wanted to make an album that was somewhere in between that could do both in a way that uses the sounds and the vibe of the rave, but infuse it with the vibe or the artists that I was listening to most at home.

View this video on YouTube

So what’s the status of Hot Natured now? Is that ever likely to come back now that you’re feeling a bit more vindicated in that approach?

Definitely. We’ve toyed with the idea for years. We’ve tried to go back and we have made music over the years—it’s just never seen the light of day. We all went off and did our own things and everybody was at different stages of their personal lives, but last year, we tried to get all four of us together again. Ali and Anabel Englund have made a couple of great songs, and there are a few things with the others as well... I actually had dinner with Lee a couple of nights ago and we were saying that we need to make time this summer and start that again.

When we’re all making music together, it feels really special. There’s a certain vibe and synchronicity that happens when we’re all together. When we have come together briefly over the years, to try again, it’s been fantastic. It’s just that there always seems to be something in the way of releasing the music. Someone’s got an album, someone’s touring too much, someone’s breaking up with their girlfriend [laughs]. Something is always going on, and we all have our own careers as well. So it’s not everybody’s main focus. It’s hard enough that there are four people in a band anyway, but if it’s their main focus, then that’s what you make the time for. But we just have to, I guess, make it our main focus again—like it was ten years ago—for it to come of anything again. But it’s definitely going to happen.