Back in 1999, UK garage outfit Artful Dodger and a then-unknown singer by the name of Craig David joined forces to release “Re-Rewind”, a song that has gone on to become so memorable that everyone under the age of 45 will probably know every word (well, the chorus at least). Some things in life gain more appreciation as the surroundings in which they are later consumed, evolve. But at the same time, if things don’t evolve, it’s easy to get left behind. For example, Blockbuster was once the go-to video and game rental spot for many years, but now it’s £1 stores and coffee shops that occupy those same shop-fronts.

There’s a balance to be found in juggling old-school comforts with new-school technologies, and the job of an A&R somewhat fits this description. Identifying talent is still the aim but in an era where numbers can appear to override gut instinct, finding that sweet spot between the two is a skill that only becomes valuable with time. “Re-Rewind”, which hit No. 2 in the singles chart, was one of the first songs that Glyn Aikins signed some twenty years ago: he was DJing across the UK with rap radio legend Tim Westwood and saw the reaction the track got in every city. Riki Bleau’s first venture into the music business was with Channel U in 2002: they were looking for content, he brought them a bunch of videos from artists who couldn’t get played on MTV Base, and later joined the company as Head of Music & Programming.

With over 20 years worth of experience in the bag, and a list of signees that include Labrinth, Emeli Sandé, Naughty Boy and Krept & Konan, Glyn and Riki teamed up to launch Since ‘93 in June 2018, a sub-division of Sony Music and an ever-growing powerhouse within British music. Since ‘93 is currently the home of Fredo, Aitch and Loski, as well as other artists like Amun and Serine Karthage.

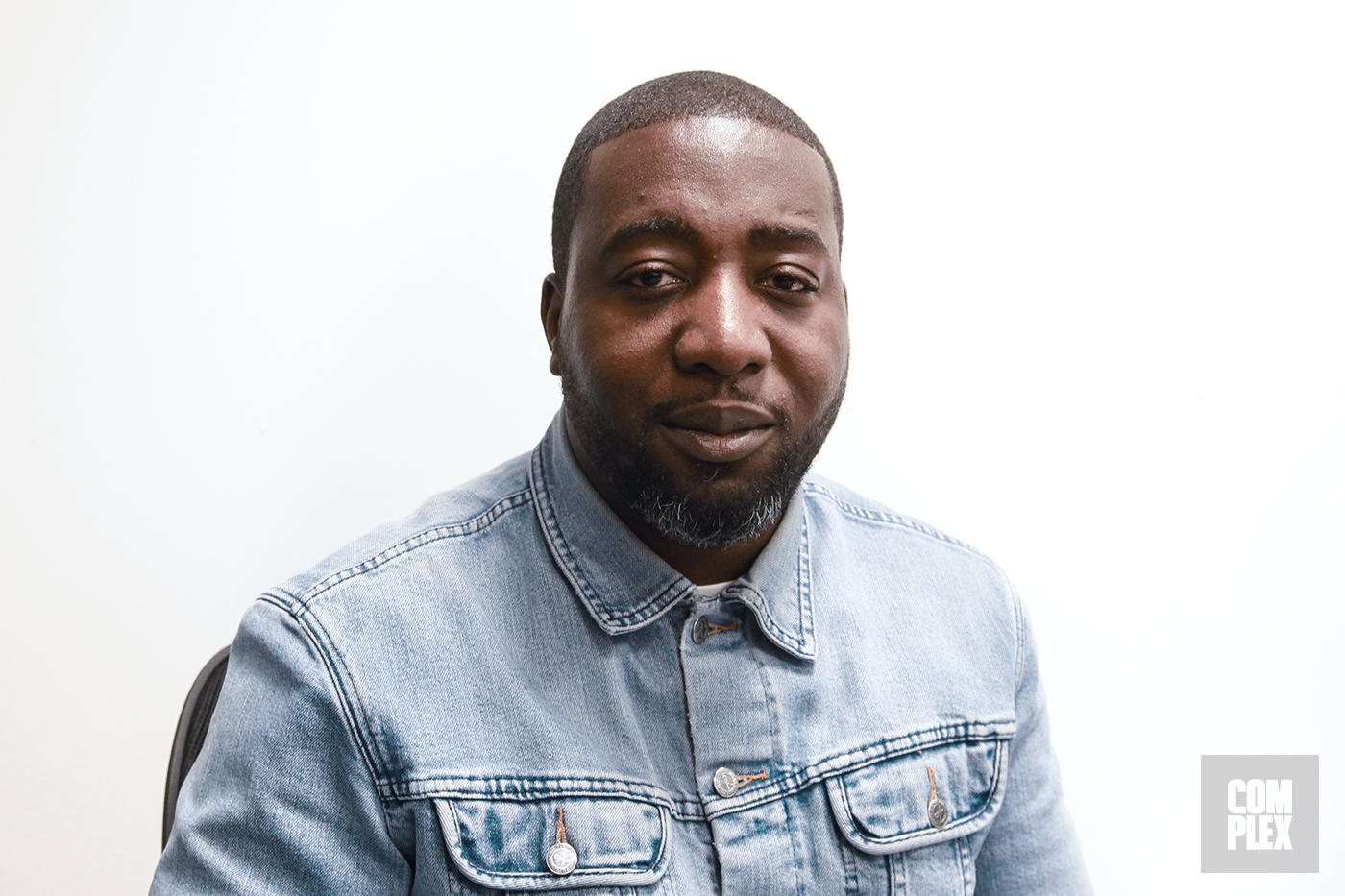

Complex went down to the Since ‘93 HQ in West London to speak with the music execs about their new stable—which bridges big-label experience with street-level understanding—and the lessons they have learnt along the way.

“The overall ambition is to be the best, and you can’t say that if you’re living on past glory.”—Glyn

Both of you have been in the game for a very long time. When did you first get into music, and why?

Glyn: In terms of working within music, I didn’t actually know that was a real option until I was at university. I was a DJ—I used to throw parties. Those were the days of vinyl so I was in record shops all the time. I met this woman that worked in a record shop who also worked for a PR company, and because I was in there all the time, I got to know her. One day, she said to me: “Look, why don’t you come and do some work experience.” That was the first point at which I realised it could actually become a real job, so that’s what set me off with my career.

Riki: At school, my friend’s were really into hip-hop, but I only discovered hip-hop really myself during secondary school. I was quite late; I was into dancehall and reggae, or ‘ragga’ as it was called at the time. So I kinda got into hip-hop quite late, and a couple of my friends had a rap group so I joined the rap group, as you do when you’re 14 years old [laughs].

Glyn: Yeah, don’t ask me what my DJ name was either [laughs]. I’m definitely not saying!

Riki: We were just mucking about in the school playground, it wasn’t serious, then we put on an event when we were 16—the last year of secondary school—and I think after that point was when we started thinking we could actually do something with music. We then evolved into a wider group and started releasing music; we had a mixtape that we would sell on the streets, and did interviews and freestyles for Tim Westwood, [DJ] 279 and Shortee Blitz’s shows. It was on that journey of promoting our music that I met the people that were starting the channel that became Channel U.

Iconic channel. You actually took on a role as Head of Music & Programming at Channel U in 2002. Looking back now, how much of an impact would you say that channel has had on the scene?

Riki: I didn’t know it at the time, but I would say that the channel was an important part of shaping what black British street culture is now. I was an active artist trying to promote music; couldn’t get on MTV Base, because unless you had a shiny video that cost thirty grand, rapped with an American accent and were signed to a major record label, you did not get played on MTV Base. If you watched MTV, it was America pretty much that you were seeing, unless it was R&B or a UK rapper sounding American and projecting an American image. Channel U became the place where you could just be you. It became the place where anyone could put their content up because the cost was little-to-nothing. People were shooting videos on handheld cameras and you could get on TV with that.

I remember, the group that I was in at the time, we had just shot a video that cost six grand. That was a lot of money at that time. We had the video for like eight months, but there was nowhere to play it. We’d shot this video, done all the hoo-rah, but had nowhere to go. And there were a lot of people in that same scenario. So when I met Channel U and they told me they were starting this channel and were looking for content, I knew loads of rappers—just like me and my guys—who were needing somewhere to put their content but didn’t have anywhere to go with it. So I turned up with a bunch of tapes from a bunch of people—Estelle, Big P, loads of people on the circuit at the time—and they were like, “Why don’t you just do this for us?” I was like: “Sweet!’” In my head, I thought I was going to put myself on the channel and get all the connections that come with that. Then I realised pretty quickly when I got there, no one would respect me picking the videos and having my own video up there.

I knew straight away that wouldn’t last very long, so I made the decision to manage the group and do what I was doing. I say this now as an example to people who tell me I was never a true artist, and that a true artist can’t just leave the art like that to do business. It just doesn’t work like that. That was what happened—the channel blossomed and it became a sense of identity. People up and down the country, in council estates and whatnot, could look on the TV and see themselves, see their friends, and things they identify with. You dress like me, you talk like me, you look like me—there was that sense of appreciation of British youth culture. The timing of that, certainly around the explosion of grime, it was just a perfect marriage.

Two decades ago, Glyn, you signed Artful Dodger’s track “Rewind”. Nowadays, there are a lot of statistics available to inform decisions about which tracks or artists get signed—but what was the decision-making process like back then when you had to rely more on instinct and less on numbers?

Glyn: The PR company that I worked for at the time was called Media Village, which turned into Relentless Records. We were doing a PR campaign for Activision, who had made this Wu-Tang Clan beat-em-up game, a bit like Street Fighter. I organised a national competition—we went round various cities in the UK and Scotland, organising ‘heats’—where people would compete and the winners get to come to London for a big final. We did it in the guise of parties. So, me and Tim Westwood, we went around the country hosting these parties in places like Manchester, Leeds, Edinburgh, Glasgow. And in every city we went to, “Rewind” would play in the club and people would go mad. I was like, “Woah! This tune is massive.” It was based on that: me seeing the reaction to the song. At the time, UK garage wasn’t necessarily played so much in R&B and hip-hop clubs. But I figured: if the song was played in those clubs, it means that it’s spilled out of its scene so there must be more to it. Seeing that let me know that this thing is more popular than anybody might think it is. It was more of a gut instinct.

Riki: In that era, before YouTube and these other markers, the difference was you just had other markers. You had other ways of measuring things up, like how it goes off in the club or where you might hear the song.

Glyn: That’s exactly it! None of it was scientific.

Riki: It was a vibe!

Glyn: It was just gut instinct A&R. You get a hunch because you’ve seen it react in places you thought it wouldn’t normally get a reaction in.

Riki: The good thing is that, being from the old school, you get to blend both. There are some things you still feel inside that stats can’t tell you.

Glyn: If you’re going to use statistics, you also need to use your instincts too. It’s all about a feeling, for me. If you can feel it, then you should probably trust yourself and think, “Okay. This is actually quite good, and there are probably other people who are going to like this other than me.”

You then signed So Solid Crew in 2001. Even though they were popping on the underground circuit, did you see them as a risk when you initially signed them?

Glyn: At the time, I was quite young, so I didn’t necessarily see anything as a ‘risk’. Actually, I guess I had a more rebellious outlook. It was a case of thinking that, at the time, everything started to sound purposefully pop with the intention of trying to make ‘hits’. What So Solid were doing was at the other end of the spectrum—it was fuckin’ exciting! They had their own movement. There were two tunes that were also going off back then: “Dilemma” and “Oh No”. Those were the first singles that I signed from them. What happened was, with “Oh No”, in those days it was CD singles and there were strict chart rules. You can have your main version of the song and three remixes or whatever, but it’s all got to add up to 20 minutes of music for it to qualify as a single. That was the rule. We made a mistake and didn’t know that, and put a few extra remixes on, so it was disqualified as a single and ended up in the budget albums chart.

People think we did that on purpose and it was some sort of anti-establishment, middle finger-type move, but it created some wave of excitement around them. Even though the song wasn’t in the singles chart, it was such an interesting story that they ended up on Top Of The Pops. “Oh No” is only three of them—Mega, Romeo and Lisa—but they were like: “There’s more of us and we want to put everyone on a record.” I said to them, “As long as you do it in three-and-a-half minutes, the length of a radio edit, it’s fine.” They then went away and devised the whole thing, and put 10 people on a song for three-and-a-half minutes. Divide three-and-a-half minutes by ten, and it’s 21 seconds. Everyone’s got 21 seconds. That’s how “21 Seconds” was made.

Riki: Crazy.

So “21 Seconds” was made in that style to fit the rules of the chart?

Glyn: Yeah, yeah. That’s how they came up with the concept for the record, and then the moment around that was the video.

That video is still so iconic.

Glyn: The video was crazy! I remember when the first edit came in, I was on my way to a meeting and I was called back to the office like: “You must see this!” I remember watching it thinking I’d never seen anything like that before.

Riki: I remember being at home, not in the music business, watching that video, watching them perform live when they came flying through at the MOBOs, thinking: “Fuck me! If they can do that, surely we can!” Literally, that moment inspired me to think that I could actually go and do something with music.

Glyn: At the time, I probably had blinkers on and wasn’t fully aware of the impact it had. Subsequently, people tell me all the time that this was the moment they thought they could actually pursue a career in music. I guess it was a market in terms of culture, in terms of British music history, and what it laid the foundations for.

“When you meet us or interact with our brand or artists, we want you to be able to feel the difference. We want you to feel that this is by us, and for us.”—Riki

When I was growing up, if you wanted an artist’s album, you had to like them enough to pay £10 for their album or a few quid for the single. Nowadays, you can access thousands of albums for just £10 a month, instead of paying £10 for just one CD. What’s the difference between trying to secure hard album sales and trying to secure huge streaming numbers?

Riki: The fortunate thing about it is, they’ve found a way to measure the streaming element to give you some kind of version of what the single CD would’ve been. So X amount of streams is equivalent to one album sale. With the advent of how popular the internet is, this is just how people consume music now. There was a period where you couldn’t really measure it, so it made it seem like music wasn’t as popular as it was or that certain acts weren’t as popular as they were, because you couldn’t measure it.

Glyn: The way that people consume music now, it’s all about ease. But it means that people can sometimes like songs, rather than artists. So the challenge is finding alternate ways to engage people with an artist and their story and personality. Garnering that interest in artists is slightly more difficult to do now, but I don’t think it’s a lost art. People still love artists, you just have to find ways to communicate that.

Glyn, you joined Virgin Records as an A&R in 2003, signing Roll Deep, Lethal Bizzle and Naughty Boy. This was around the time of the first ‘boom’ around grime—what was it like to be involved in that early wave?

Glyn: Roll Deep had almost an entire album that was done at the time, and I remember meeting them but I was kinda already connected to them via Wiley. One of the first records I signed was this record called “Nicole’s Groove”, a garage tune by Phaze One—but Wiley produced it. After “Rewind”, that was one of the first things I signed, so that’s when I met Wiley, way back then. That’s how I knew Roll Deep, so they were already familiar with one another and it just seemed like a natural thing to do. I don’t think we were even thinking about ‘working in grime’, or whatever. These guys were just exciting—Wiley’s already exciting, isn’t he? So that’s how that happened. Funnily enough, although I had met Riki before, signing Naughty Boy was when we first started working together, some time ago.

Riki, you signed Labrinth in 2007, right? I remember there being a period where “Pass Out” dropped and then a few more Labrinth songs dropped, and it seemed like—out of nowhere—Labrinth was huge.

Riki: From the point in which we signed him, to when all of that happened, was pretty much two years. But when I met Labrinth, I was doing a talk in a youth centre, in Hackney, talking to kids who wanted to get into music. The point of the program was to engage young kids in music who might have otherwise been involved in some nonsense on the street. Labrinth was the music teacher and was the same age as the kids that I was talking to. My pal, that asked me to come and do that talk there, said to me: “Labrinth’s got some good stuff. Can you check out of some of his music?” I listened to it. He had “Let The Sun Shine”, then. He had no idea that he was an artist—he just saw himself as a producer and a writer.

Prior to that, I’d met Tim Blacksmith and Danny D during my time at Channel U. They were the first people I met who were into publishing and they kinda taught me about publishing and said, “If you ever find anything, let me know.” But I didn’t connect the dots between what people like Tinchy Stryder and DaVinChe were doing—I never saw these guys as songwriters. I didn’t quite understand the concept back then. I thought a songwriter was a white guy with long hair and a guitar—I didn’t see artists and people who I was actually around, as songwriters. So I never suggested these people because I just didn’t make the connection. Then I came across Lab and sent his music to them and they liked it. We ended up meeting them and, long story short, he became the first signing I’d done on this side of the business.

That led me to signing Naughty Boy after that. He had a MySpace page with “Daddy” and all of those songs up there. Glyn had already met him; we had a conversation and he had mentioned Naughty Boy. Long story short, we went and met him and started managing him. Labrinth’s quality led me to recognise Naughty Boy’s quality, if that makes sense? It gave me a barometer for what was really good. One thing led to another, because Naughty Boy was working with Emeli Sande, so their music was all intertwined. These events were like the beginning of mine and Glyn’s working relationship—unbeknown to us—and in a very short period of time, all of these artists went on to realise their potential in a major way. Hit records, Ivor Novello awards, BRIT awards, millions of sales. You mentioned before that, all of a sudden, Labrinth was everywhere, and that kind of happened with all of our acts in a two-year period. It shifted what was pop culture at the time.

There were so many artists that came from those creatives that we just mentioned. You could say that Tinie Tempah was the leader of that new generation as the ‘rap act’, if you like, which was pretty much powered by Labrinth, Naughty Boy. Emeli Sandé was writing the hooks on those projects, too. These creatives were actually shaping the sounds of the records and the artists that were coming out. Professor Green: same thing. Underpinning a lot of those sounds were these artists behind it, making records, writing songs and all the rest of it.

Emeli Sandé is pretty much a pop/soul legend at this point.

Glyn: I remember sitting talking to Naughty Boy, and we had the most interesting conversation. He played this song, and it turned out to be “Never Be Your Women” with Wiley and Emeli Sandé. Of course, I knew Wiley, but I said “who is that singing?” and he told me it was Emeli; that’s how I first heard Emeli. At the time, she was still a medical student and he was flying her down from Scotland to come to the studio and make songs. That’s how I met her.

I think Emeli is one of, if not the best songwriter and vocalist of her generation, and the result of her debut album, Our Version Of Events, shows that. Some five million-plus albums sold around the world, with three million of those sold in the UK alone! When she was doing these numbers, it was more than Katy Perry, Taylor Swift and Rihanna combined. On top of that, Our Version Of Events broke a record set by The Beatles for the most consecutive weeks spent in the UK Official Top 10 by a debut album.

Before Since ‘93, you worked in A&R at Virgin EMI and signed Professor Green and Krept & Konan. With Krept & Konan, they got a record deal after Young Kingz charted in the Top 20. Then their debut album, The Long Way Home, was a top five album. How do you go from a ‘good’ achievement to a ‘great’ achievement?

Glyn: I think that’s just down to ambition and the artist’s ambition. They wanted to be great and they wanted to be the best. I remember talking to them, they came at the time when the rap music of the day, in terms of sales, seemed to be in decline. With Young Kingz, “Don’t Waste My Time” was a super-hard, underground sound. People asked me why I was signing them but it’s funny, because I remembered the rebellious spirit from So Solid, but also, what I think I learned from So Solid is that when people start to get bored of one thing, they always go to the other end of the spectrum, which is normally the underground. The things that are popular there, that’s what everyone is paying attention to now. “Don’t Waste My Time” was arguably the biggest anthem at the time. After having met Krept & Konan, they told me what they wanted to achieve and what their ambitions were. I said, “I can help you do that.” But it’s always based on that and what an artist wants to achieve.

In June 2018, you both launched Since 93. As two veterans in music…

Glyn: You’re making me feel old, man!

Riki: Say young vets! [Laughs]

[Laughs] As young veterans, what did you want to achieve?

Glyn: I think the overall ambition is to be the best, and you can’t say that if you’re living on past glory. I don’t think anything should purely exist on former glory. You want to be creating an environment where success, small or large, can be enjoyed, and that’s part of the thing that drives us.

Riki: As well as ambition, it also becomes almost like a natural progression. We’ve both been students of different schools of thought from successful people in the music business, who taught us and helped to nurture us. What we’ve done is took the best of those learnings and created our way of doing things, and now we’re here at a point where we can actually do that for ourselves and from our own perspective. It’s not like we’re doing something that’s fundamentally different now—we’re actually doing what we’ve always done—we’re just doing it together and for ourselves. The game doesn’t really change. We were talking earlier about how to read songs before the internet, and Glyn, he had a way of reading songs and that’s that’s prepared him now for a time where he’s got the best of both worlds. And that’s why I think he’s the best A&R in the country, because he’s got the old-school instincts of a killer A&R plus all these fucking stats! Great. Just great.

Glyn: Riki is also fundamentally amazing with people and, ultimately, this is a people’s business.

Riki: We also touched upon how we’re in an ever-changing world. Similar to how we move from CD sales to streams, you’ve also moved from an attitude of feeling like you needed a record label to do everything, to feeling like you’ve got to do a lot of it yourself in terms of development, before you get to a major. You’ve ended up having to do far more than historically you needed to do in terms of growing and building your acts. The synergy between what Glyn has always done as an A&R and what I’ve always done as a manager/publisher A&R, collectively, I think these skill-sets have put us at the front of the queue.

You signed Fredo, Loski and Aitch quite early on; seems like you guys had a clear vision and executed that quite quickly.

Glyn: The mission here is to be working with the most exciting artists around and helping to nurture and guide their music career. That’s the vision. Collectively, individually, we recognise that in Fredo, Loski, Aitch, Amun, Serine Karthage, we think that they’re the most exciting people around. We don’t want to be lazy record people company and just follow the trend. The mission is to always be aware of where the crowd is going and to just go the other way.

Riki: To add to what Glyn said—without sounding like an asshole, there actually was a strategy of hitting the ground running and that was a discussed thing. Again, this is where experience helps you. We’ve been around long enough and seen enough iterations—especially Glyn, from a record label perspective—to know that momentum is key. With everything you do, momentum is key. Sometimes you can be a bit too reserved and you want to get everything a million percent right, all in one go. Our thing is, let’s just be excited about things. So with the likes of Loski and Fredo, exciting acts in their own lane. Then also, Serine Karthage, Amun, starting from zero—there is nothing on the YouTube to look at—that’s where you go back to your gut and think, ‘I just think this is good.’ It’s not led by stats—this is just good! Now, it’s our job to get everybody else to see that this is good, but we fundamentally believe that this is good. There were no markers for that. Aitch just started, and he’s really bubbling and growing nicely.

Glyn: And after meeting Aitch, you’re like: “Yeah, this guy… This guy’s got something.” And that was it. It’s about belief. We’ve seen people do things like this before, where they have a label connected to a major label and whatnot—what they do is sit around and wait for the perfect artist or perfect beat to walk through the door and, invariably, that doesn’t happen. And when that doesn’t happen and you’ve been sitting around for a few years doing nothing, then the pressure comes, you panic and start signing any shit and end up running up the down-escalator and shit. It just doesn’t work. We need activity, and to get things going on. That feeds back to the thing of they won’t care if you haven’t got a number one hit. Our concern is to create excitement and create a culture for what this place [Since ‘93] stands for, and what it means. Particularly for the artist community to know that is a place where you can come and collaborate.

Riki: I made a point earlier about the shift in culture. There was a point a little while back where being independent was a badge of honour. With both of our skill-sets and experience, we’re able to create an environment that has a degree of independence within it, so people walk in and feel like we can be disruptive, we can be different. We work too hard to retain the elements of independence that we have being in a joint venture. We can be as corporate as we need to be, but we can also be the man on the pavement as much as we need to be, so you’ll find us somewhere in the middle.

Glyn: You want to meet an artist’s needs in the best way you possibly can. So if there’s a feeling that an artist wants to be disruptive, you also know that, when the time comes, should you need it, you’re also connected to a global powerhouse that can take you and your music all around the world.

Do you envision the recent commercial success of UK rap and drill lasting the distance? Reason I ask is because grime has encountered many peaks and troughs, high and lows—but will rap enjoy more consistent success?

Glyn: It’s difficult to say. On a cultural level, going back to the point of how people consume music nowadays and what music is the most popular—in terms of consumption, I would generalise it and basically say if you’re young, you listen to rap music, no matter who you are or where you are. Perhaps it’s always been that way and before, we couldn’t measure it, but now we can.

Back in the day, a lot of people would reject rap music unless it came from an American artist.

Glyn: Things have definitely evolved. When I was younger listening to rap music, the debate was—as you said—could you be taken seriously if you didn’t rap in an American accent? Now, the majority of rap music you hear is in a British accent. It’s frowned upon almost to do the opposite. People just inherently gravitate towards their own, so American rap music may not necessarily be as dominant anymore.

Riki: If you go to a nightclub in London, you will hear Drake—don’t get me wrong. You’ll hear the big song of the day, 100%, but you go into clubs and all you hear is UK music, all night. And you don’t even notice, until you notice. Whereas before it would be like so, are you not gonna play the new Snoop Dogg? You would notice they’re not playing it. It was like you had to ask the DJ for the big tunes, but there are plenty of big tunes now that exist within the culture that these young guys are putting together. There’s new music being released every single day.

What can people expect next from Since ‘93?

Glyn: Rock and fucking roll! [Laughs]

Riki: The good times are back, mate! Our whole thing is, when you meet us or interact with our brand or artists, we want you to be able to feel the difference. We want you to feel that this is by us and for us. The artists feel that way; when you’re dealing with artists who are uncompromising kids from the streets like Fredo or Loski, they’re not going to be comfortable walking into massively stiff, corporate environments. I don’t have to tell you that for you to know that’s going to be true. We pride ourselves on the fact that we’re able to make the experience for them as comfortable as possible, while aiding their growth as young men, because we still give them the corporate parts of the experience they need and deserve because their talent deserves that. You do have a marketing person, you do have a product manager, you do have a radio person, and here is that wider team. They’re not bad people either. That aids people’s growth. We’ve seen how much these two [Fredo and Loski] have grown in the last 12 months as human beings from their music careers. It’s real for them. This is providing for them and their families like nothing before has. You can’t take that for granted.