Bubbling is a monthly series highlighting emerging artists on the cusp of major breakthrough.

“Come get your face painted, baby.”

I’m spelling it “b-a-b-y” because that’s the only way to quote what is being said to me in writing, but in this room, it doesn’t sound anything like it reads. The vowels are massaged and finessed, buttered and dredged, the emphasis delocated, in ways that defy common usage. In New Orleans, colloquially, “baby” is not necessarily an intimate term. It can serve as a general address. A Church’s Chicken cashier can be “baby.” A mailman can be “baby.” A journalist you’re meeting for the first time can be “baby.” It works functionally as a title and as punctuation, but it’s actually a secret handshake, an induction into an insular society.

I’m on the east side of New Orleans, a hazy dreamscape physically apart from the continental United States, on the banks of the Mississippi River at 3:30 in the morning on Fat Tuesday. I’ve just been welcomed into a Hampton Inn conference room by Miss Christy, the manager and mother of Rob49, the most significant and visible rapper to emerge from this city in a generation. In several hours, one of Mardi Gras’ storied parades, the Krewe of Zulu, will begin, and Rob has invited me to ride with him. He greets me with a smile, “Wassam Baby,” attempting to give me a pound, seated without moving, as he’s getting his face painted.

There’s a palpable New Orleans influence in Rob’s music, and his affable personality, in spite of his dour delivery. An accent is at once a detail and a definition for a rapper. This is particularly the case for Rob, whose sizable fanbase often points to his voice and his accent—a deeply southern fried, salty, spicy interpretation of the English language—as the main characteristic that draws them to him. It’s a reminder that where you’re from is embedded in you in ways that defy style and taste. It’s woven into your DNA. Rob’s friend and mentor, the rapper Neno Calvin says, “We just New Orleans n****a. You can't duplicate this shit or replicate it. When you open your mouth, you could be Rob49, Jay Electronica, Curren$y, Cash Money, No Limit, it don’t matter. These people got their own distinguished music, but you still can hear the New Orleans in they shit. You can't hide that shit, bro. It's going to come out.”

Rob49 is 24 years old. He was born in the midst of No Limit and Cash Money’s global explosions, establishing New Orleans as a premier American rap city. Rob went to high school at Mcdonogh 35, a charter in Gentilly, but famously grew up between the Iberville projects of the Fourth Ward, and the Ninth Ward, where his family stayed, which lends him his unusual, AIM-like rap handle. Those wards, and the greater city, have been imperiled on all sides his entire life, by rising sea levels in an already below sea level city with no solid foundation. By saltwater encroaching on the freshwater the city runs on. By gentrification, crime, and a soaring murder rate. In his brief life, Rob has lived all over New Orleans, but also in Baton Rouge, Houston (where he had to relocate after Katrina), Georgia, and Miami, where he’s resided for the past two years.

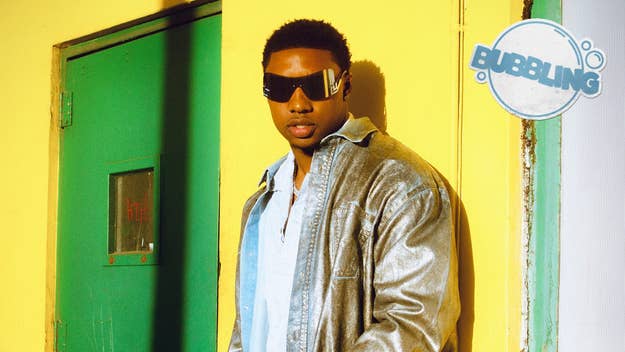

Rob is tall with an athletic build, and still looks like the high school basketball player he was before an injury derailed that dream. Aside from a few years in high school selling weed, he kept out of trouble, graduating and spending time in the National Guard and a nursing program at Southern University. When you spend time with Rob, it’s easy to imagine if he hadn’t tried his hand at rap, he’d be on his way to a sturdy career in nursing, with the same close relationship to his mother, father, and sister he has now. It’s a quality that helps explain how he made it out of New Orleans, and why the bullshit he’s had to deal with as an ascendent young rap star can be so frustrating to observe from afar.

He is an autodidact who made his first song during COVID, fucking around while his aspiring artist friend was in the studio. The song immediately caught fire, as did Rob as an artist, signing to Say La Vie under Geffen Records within a year. He’s now on the verge of releasing his seventh album in less than four years, with a number of viral moments and a stunning resume of features on his CV. With no business interest in his music, Birdman jumped on the intro to 2022’s breakout project, Welcome to Vulture Island, on a song titled “Birdman Pass The Torch”. Just a few other notable collaborators include Travis Scott,Lil Baby, Kevin Gates, Babyface Ray, NoCap, Trippie Redd, Skilla Baby, and poignantly, on his hit “Wassam Baby,” Lil Wayne. “He did everything right,” Neno Calvin explains. “Marketing, this, that, and the third. He knows how to play the Internet. He knows how to play the game.”

Rob doesn’t rap like an artist you’d historically associate with New Orleans, and this was by design. It’s a city of brass doused in vinegar-based hot sauce, and this has always been a hallmark of its rap music. It’s singsong, but not in the sing/rapping hybrid sense. The city’s MCs have always spit with their whole spirit, with a distinct musicality. Juvenile delivers in sung pidgin English, like a cantor braying the torah with his eyes closed. Soulja Slim is closest to Rob in New Orleans parentage because both baritones sound like they’re emanating from a burning bush (or ordering for the destruction of planets from a command on The Death Star). But Slim’s verses are larded with vibrant melodies that span the scale from bar to bar.

Rob49 is different. He raps with his ears pinned back. He is closer to the ice-veined and humorless drill rappers of Chicago, venting furious rifle fire, the words more barked than sung. He has a predilection for ugly, menacing, low-end-heavy beats with repetitive, minor key melodies, with very little in the way of the city’s beloved humid bounce. One of his favorite rappers, and clearest references, is his now friend and collaborator, Chicago’s G Herbo. Influence is rarely a simple formula, but Rob says, “I was mimicking Herb and Future growing up. Herb ’cause he trenched like me, and Future with the sauce,” and this is a fairly accurate equation that bares out the deceptively complex style he employs. Rob has consciously moved toward a Midwest delivery, a less regionally specific style, because he doesn’t want to lean on New Orleans for his identity as an artist, explaining, “I remember going in the studio and was like, I was trying to be the biggest in the world, not the biggest in the city.”

Despite his relatively easy rise to prominence, Rob has expressed an indifference towards rap and maintains he’s going to retire at some point in the near future. It comes naturally to him, and he’s good at it, but he’s a Jokic-style prodigy, generally uninterested in the work that has made him great. When I ask him about it, he tells me, “I just don’t feel like doing it. It’s work. I like being by myself.” He’d rather be chilling with his family and longtime girlfriend. When you consider his turbulent few years as a star in this current rocky, dangerous climate for young rappers, it becomes easier to understand why he’d want to get out while he still can.

The Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club has existed in New Orleans since the early 20th century. It was an outgrowth of benevolent aid societies. Mardi Gras is an event that can feel like a frat boy bacchanal depending on the parade you attend. But there is a rich history behind the Zulu parade, and a genuine local enthusiasm for the ritual and celebration. As per tradition, most float riders wear what might appear to be blackface to the uninitiated, with afro wigs. Each Mardi Gras parade has a talismanic, coveted token specific to its event—for the Zulus it is a hollowed-out coconut. There are many ways to interpret the manner in which the Zulus continue to dress for the parade. Most have just accepted it as part of tradition.

When I try to explain to Rob and his family, who I met minutes ago, that I don’t feel comfortable dressing like a Pierre Delacroix nightmare, they’re all genuinely baffled that anyone could interpret the costume as anything mildly offensive. It’s explained to me, several times, as a self-evident fact, as you might say to a person who is lost, “No, no, baby, it’s not racist, it’s New Orleans.”

Mardi Gras is composed of a series of parades through the city that attracts people who come to collect prizes (“throws”), which are often long necklaces of colorful beads that, as the name suggests, are tossed by members of the organization sponsoring each parade, from the height of the float into the crowd. The beads that the people clamor to collect are worthless costume jewelry that lose all their value the moment the parade ends. Mardi Gras is a social contract, one that if either the riders or the crowd thought too hard about, would lose all value and meaning, which is precisely what makes it special.

The riders all start drinking when they begin prepping the float in a gravel lot miles from the start of the parade route at 3:30 AM. During the parade, they’re like DJs, controlling the crowd’s energy as they toss their throws out to a very drunk, adoring crowd. This is Rob’s second year manning a float at Zulu. After choosing not to get in costume and riding the float myself, Rob convinced me to follow the float in his heavily armored Cadillac Escalade with two-inch thick windows. If New York is a theme park for adults, New Orleans is a daycare. Everyone is playing dress-up and make-believe; everyone is silly and churlish; everyone is drunk off juice and gets the zoomies from sheer exhaustion-induced madness. This morning, these are Rob’s people, and throughout the day, it’s apparent how much he means to them, and how much they mean to him.

The event isn’t some premeditated PR stunt for Rob, but a fantasy camp experience. He didn’t promote that he’d be riding in the parade on his socials beforehand. He’s not at the level of fame yet where he’s instantly recognizable to all. But even then, he’s unrecognizable to most from a moderate distance in facepaint, a wig, and the same blue and red frock everyone else on the float is wearing. This isn’t new for Zulu. In 1949, Louis Armstrong served as the parade’s Zulu King. “As you look around, you'll see a lot of people on those floats that you wouldn't even imagine,” explains 2024 Big Shot Krewe captain Shan P. Williams Jr. “Big Freedia rode a float. NFL players, NFL coaches, you just don't know because everybody is in costume. So with Rob being on the float, nobody treated him like a celebrity. We just let Rob and his family have a good time.”

Rob, who spent an estimated $5,000 to have himself and four family members on the float, puts the value of the experience into context, explaining, “Growing up? Zulu was always something everyone in New Orleans wanted to be a part of. Especially kids from the trenches, we just never had no money. It feels crazy to me because I’ve never seen it from this side. They used to be real picky about who they throw stuff to when I was coming up, so to be able to throw it to the children who really look like they want it meant everything.”

Throughout the day, I get to watch kids freak out as they are told the guy in face paint with a wig on the float is Rob49. Rob is just as excited, exuding childlike joy and enthusiasm throughout each step of a marathon parade. Mixed in with a soundtrack of bounce remixes of 90s R&B classics, a stream of Rob’s greatest hits are being played by sidewalk DJs as the crowd raps along to his lyrics, unaware their author is a few feet away, soaking in the feeling of owning the city he grew up in and still loves.

In that spirit, let’s break for a moment, for those who’d like a primer of Rob49’s already extensive body of work:

The Definitive Ranking of Rob49’s Five Biggest Hits in Terms of Crowd Response at the Krewe of Zulu (2/13/24)

5. “Penthouse”

4. “Hustler”

3. “Homebody”

2. “Wassam Baby” (I didn’t appreciate how brilliant this song was until I was actually in New Orleans. It’s not some slang Rob is trying to get off the ground. Everyone answers the phone with that greeting in the city at the moment. It’s an example of his canny mining of local and specific trends to manufacture universal hits.)

It’s arguable that New Orleans hasn’t minted a new national rap star since the aughts. Khaelyn Jackson, a New Orleans photographer who has worked with Rob several times, says, “It’s like a curse here. You can blow up in New Orleans, but you don’t get any bigger.” Neno Calvin attempts to put Rob’s rise into perspective, explaining, “I feel like it happened for bro so naturally because he came in the game, he didn't have no beef, no problems streetwise. It wasn't hard to say, ‘Put on that 49.’ That was a great thing because a lot of artists from New Orleans, they got street shit going on so half the city might not support them. With Rob, it’s different. He came in as a young n****a, clean face, talking to the hoes. So it's like, if you hating on him, you just a fucking hater. He’s a kid with no history.”

Because Rob came in insulated from the street violence that has taken a number of promising young New Orleans rappers who never had a chance to make it out, from Lil Derrick, to Jiggamoney, to Young Greatness, he was able to unite the city as an unproblematic artist who had no designs beyond putting on for New Orleans. During Rob’s “Vulture Island” video shoot in the spring of 2022, he brought Kevin Gates and Lil Baby to the Iberville Projects and the city briefly set aside its petty feuds and beefs to unite for a few hours. Even the mayor of New Orleans was there, singing along. Khaelyn, who was taking pictures of the shoot that day, says, “It was historic, for people to be able to come together, and no one is getting hurt? He's the only rapper that I've ever seen who could mobilize the whole city like that. In New Orleans there are two Robs. Rob before that video shoot, and Rob after.”

Rob has done nothing but give back to New Orleans with gestures like riding a float at Mardi Gras and throwing a celebrity basketball game he hosted last year at Mcdonogh. And yet, his young career has been beset by the violence that seemingly plagues all young rappers of this generation. That Rob should feel the need to move away from his home city and to ride around in a car outfitted like a tank is depressing, but entirely justified. In 2022, in his new home of Miami, he was shot during the filming of a French Montana video. Several months later, in an incident Rob will neither confirm nor deny when I ask him about it, Miss Christy was allegedly involved in a life threatening incident in New Orleans. The day after Mardi Gras, on Valentine’s Day morning, after a performance at club Metro in New Orleans, minutes after we parted ways, Rob was allegedly involved in a shootout in front of the Four Seasons Hotel where he was staying downtown, which he dismisses as “some stupid shit.” I ask Rob if he feels like a target, if there were any other incidents that led to him moving out of New Orleans that hadn’t been made public. He responds, “It’s not for interviews, but of course! What the hell?”

“I think with all of the attention that he got and the fact that he got it so fast, it causes envy,” Khaelyn, who is Rob’s age and grew up in the city, explains. “It's not even that you're gang-affiliated. It's like if they see that you have money, once you become successful, you cannot come back to the city. It's not safe for you anymore. With Rob, he's such a sweet person. He's such a family person. He's one of those people that tries to show love to the city, but it's hard to show love to the city when it's not showing love to you back.”

Neno Calvin moved to Atlanta several years ago, after being shot himself (nearly fatally) in New Orleans for a second time. He explains the logic, detailing why someone would come for a young artist who has been nothing but a beacon of light and positivity for his hometown: “Listen, bro, Louisiana has the highest per capita incarceration rate. On Earth. So it's like, you either going to be dead or in jail. They always preach that in Louisiana. It's n***as that grow up that be like, man, fuck it. My name’s going to be forever remembered. They will kill somebody with a name, go chill in Angola, just so they could be famous. That's famous to them, bro. They coming home, shotgun house, two bedroom, ain't got no water. New Orleans fucked up, bro. New Orleans fucked up.”

Louis Armstrong once said that when he closes his eyes and plays his trumpet, he sees New Orleans. That the city gave him his reason to live. This is Rob49’s plight. He will be from New Orleans, and will carry the humble warmth and spirit of the city with him, wherever he goes, for the rest of his life. It lent him his style and his identity. But there also may be a time it’s closed off to him. No matter how much love and support he pours back into the city, there is an element that will make it difficult for Rob and those closest to him to return comfortably. After our few days together, I speak to Rob back in New York, while he’s in a hotel in Atlanta. I ask if he has any comment on this sad paradox. He responds, with an air of resignation that carries a weight well beyond his 24 years, “It's frustrating coming home, bro.”