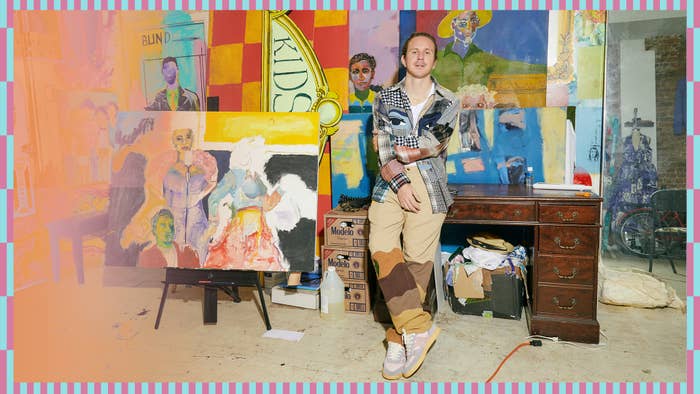

Colm Dillane’s studio in Williamsburg, Brooklyn is a dimly lit space that’s smaller than your average bodega. It’s located directly underneath elevated subway tracks—you can hear the rumble of the J train every 15 minutes—and packed with hundreds of clothing samples that complement Dillane’s bright paintings hanging on the walls. It’s difficult to fathom that this is where Dillane, the 29-year-old artist behind KidSuper, has built and grown a clothing label that hits seven figures in annual revenue.

The New York-born designer has come a long way since selling his T-shirts out of Brooklyn Tech’s high school cafeteria. Dillane never attended fashion school, but instead studied mathematics at NYU. He learned how to make clothing through YouTube videos and Google University. He built his first collection of T-shirts, hoodies, and hats when he was a college sophomore with $3,000 he borrowed from his parents. After Dillane was kicked out of NYU’s housing for running a de facto KidSuper store in his dorm in 2012, he rented a live-work storefront space in Williamsburg via Craigslist for $2,500 a month, which he still lives in and operates his brand out of today. This is where Dillane built the world of KidSuper, a brand inspired by his whimsical art that drew in fans like Joey Badass, The Underachievers, and Russ.

Since starting, he’s steadily grown the line with no additional financial help, collaborating with the likes of Jägermeister and Puma. He was recently nominated for the LVMH Prize, which he lost, but was one of the three designers to win the prestigious Karl Lagerfeld prize that grants him €150,000 and one year of mentorship from a team of experts at LVMH. But despite Dillane’s close proximity to the fashion industry having grown up in New York, his climb hasn’t been an easy one.

“Making clothing in New York is super expensive, it’s super difficult to know who to talk to, and it’s super limited,” says Dillane. “I remember [in the early days] going to a factory in the Garment District and they were showing me all this super high-end stuff they were producing. They told me it would cost $800 to just cut out the pattern for a jacket, not to even make it. [All I thought was:] ‘Jesus, how does anyone get anything started or made?’”

Dillane’s question is a daunting one for many young New York City-based designers. As clothing production has moved overseas to countries like China and India, young designers struggle to find local manufacturers that can make finished garments for an affordable price. Because of that, even small New York-based brands look to produce overseas to cut costs. But despite how expensive it is, many burgeoning designers seek to build their lines in New York to be closer to their work and to reap the benefits of domestic production.New York City has always been a refuge for people who want to create and build something, but is it still the most ideal place to start a fashion brand?

Augie Galan, a Queens-born designer who was hired to build Supreme’s cut and sew program in the 1990’s, doesn’t think so. Galan remembers when neighborhoods like Tribeca and Soho still had active fabric suppliers and trim stores on Broadway. But he says that by the early 2000s, many of those downtown stores closed because they were priced out. But the decline in New York City’s fashion industry started long before that, more than 40 years ago. Between 1958 and 1977, the number of garment manufacturing firms in Manhattan had already shrunk in half from 10,329 firms to just 5,096. And according to the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics’ most recent quarterly census, the number of fashion manufacturing establishments in New York City went down 7.7 percent from 2019 to 2020, while employment dropped 32.2 percent.

Galan, who now directs production for the streetwear brand Teddy Fresh, which is based in Los Angeles, says it’s possible to make T-shirts and sweatshirts in America, but it’s more affordable to do it overseas. But Galan, who makes makes T-shirts, headwear, and socks in Los Angeles and New York, says once designers start making cut and sew clothing—pieces with unique designs; not pre-made blanks for screenprinting—it becomes very expensive, which is why bigger brands produce in Asia because it’s cheap and easy to manufacture garments there.

“There’s a lot of stuff you just can’t make here anymore because of the infrastructure,” says Galan, who finds it difficult to produce certain items domestically due to lack of raw materials. He notes that designers have to work harder to produce on the East Coast, whereas California has a more robust manufacturing industry that is bolstered by its proximity to outsource work to Mexico. However, he admits he still works mostly with factories in China. “You go to China because they offer it to you as a complete package. You don’t have to do everything separately and it’s just a one-stop shop.”

Aaron Maldonado, the founder of the New York City streetwear brand Brigade, which has gained a cult following for producing elevated streetwear garments, didn’t realize how expensive it was to make samples in New York when he set out to produce more cut and sew pieces. Although Maldonado was able to flip the $500 from tips he earned as a pizza delivery driver to produce Brigade’s first pieces (which made him his first $5,000 to invest more heavily into the brand) he soon discovered that his profits weren’t nearly enough to produce an entire collection domestically.

“There’s a whole generation of young designers in the United States that can’t push even 100 pieces,” says Maldonado, who never went to college and launched Brigade when he was 19. “When people like me reached out to these older factories in the Garment District I said: ‘I see your minimum is 500 units, but can we do 100?’ They told me to go fuck myself, pretty much.”

But in 2015 he stumbled upon Alibaba. “It was like the wild west,” he says. There, he found factories who would work with his budget and low minimums and began producing his first real collections overseas. It has helped Maldonado scale his business to hit six figures in revenue since 2017 and garner over 10,000 followers on Instagram. But nowadays he wants to produce his brand entirely in New York City for various reasons.

Despite lower costs, working with factories overseas comes with its disadvantages. Producing in China today has never been more expensive, and according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, prices for imports from China to the United States rose 1.2 percent over the past year, which is the fastest increase since 2012. Language barriers and a 12-hour time difference from New York also make it difficult to communicate with factories in Asia. And issues that could easily be fixed by designers having easy access to a local factory can lead to costly losses when clothing is produced abroad. Maldonado recounts how he once ordered 100 pairs of hiking pants from an overseas factory and even paid extra to add YKK zippers, only to discover that half of the pants arrived with broken zippers. Despite working with this factory for four years, they refused to do anything to fix his order.

“I know that wouldn’t really happen in New York because I can go to the factory and tell them to fix it, ask them to make new pants, or ask them to at least give me a discount on my next order,’’ says Maldonado. “I don’t think outsourcing is smart in the long term because it’s like a capitalistic play to just chase the lowest price. I would like to think our generation has had enough of that.”

Additionally, it’s harder to vet a factory’s working conditions when you can’t physically visit it. Dillane says he regularly makes trips to China to check in on his factories, but admits that only happened after working with them for five years. Maldonado would stay away from factories on Alibaba with suspiciously low prices, go on Skype video calls with factory owners, and check for certain labor certifications before sending out any work. These days, Brigade has begun to work with more factories in the US and New York City. He feels the recent devastation caused by Covid-19 has pressured local factories to accommodate young designers and brands more than ever before.

Other successful designers working with the Garment District agree.

“I think the Garment District is very accepting of low minimums right now because they need all the work they can get,” says Eric Emanuel, whose ever-popular mesh shorts are cut, sewn, dyed, and screenprinted within the five boroughs. “I think New York is the best place to get started because aside from the financial hurdles, everything else is much easier and better. You’re actually hands-on with it and not working through emails, but learning because you have fabric stores everywhere, pattern makers, and everything else in your hands. You just need to be driven enough to put the pieces of the puzzle together and figure it out.”

A Fashion Institute of Technology graduate who studied marketing, Emanuel started manufacturing his eponymous brand just blocks away from his alma mater in Manhattan’s historic Garment District. He primarily works with two factories and has been with his main manufacturer for the last four years. Emanuel says he learned how to make garments by himself and plans to keep producing in New York because of the perks. Although rent is expensive, parking is limited, and he has to lug his garments around the city to get them screenprinted or dyed, Emanuel doesn’t have to worry about long wait times for overseas shipping, he can try on garments and make changes on the spot, and ship out his product from one location in midtown Manhattan. In contrast to his success today, he remembers it wasn’t easy finding a factory that would take a chance on him early on.

“I told her I needed only 50-60 pairs and she said that it was not worth her time. But I asked her to trust me because it would grow, and it eventually did,” says Emanuel, who recently opened his first brick and mortar store in Bathing Ape’s old location on Greene Street in SoHo. “We weren’t really the largest brand in the factory until about two years ago. It took two years to actually build the brand out to where they actually were happy with how much they were producing and were taken care of.”

Designers admit that they will do whatever it takes to secure a tight relationship with a good local factory. Taofeek Abijako, the 23-year-old designer behind Head of State, has even slept inside a New York City factory to plant a spot for his brand to grow. Abijako launched his own label when he was 17 by hand painting a few pairs of Vans from his closet. Actress Amandla Stenberg posted them on social media, which helped him earn $2,000 in orders. He used that as capital to fund his first collection, but then had to find a factory that would take on a designer who just graduated high school. He cold called multiple factories and didn’t get a lot of responses because of his low minimums. But he found one factory that agreed to work with him when he showed up with sketches of his collection, which is influenced by his Nigerian background.

“For them to take me seriously, they said I had to be at the factory every day and learn everything hands-on,” says Abijako, who never enrolled in fashion school but went on to become one of the youngest designers to present a collection at CFDA’s New York Fashion Week when he was 19. “From pattern-making to learning how to make a final garment. It got to a point where I spent the night on the factory couch and they were very open to the idea of this young designer looking to get started. So I’ll say that manufacturing in New York is heavily based on building relationships.”

Despite the hurdles designers face producing garments in New York, many American designers are still drawn to building their labels out here. Tommy Bogo, the 27-year-old designer behind the rising utilitarian streetwear brand Tombogo, moved from Oakland, California to New York City in 2018 to build his brand for two years before moving to Los Angeles. Bogo says he relocated because of the unique vision New York-based creatives have and he learned to become more critical of his own work while he lived there. “Fashion Week and just being able to go to shows at places like Spring Studios. Window shopping and hanging out in SoHo and the LES was really inspiring for me coming from Oakland,” says Bogo. We don’t have anything of that echelon. It was more about the creative community out there and the bars that were being set there.”

When comparing New York to Los Angeles, Bogo views New York City as the “heart” of fashion while Los Angeles is more like the “arms and limbs” because of how much easier it is to produce clothing on the West Coast. Bogo estimates that his production is split 50-50 between Los Angeles and overseas factories in Asia. But even though he found it difficult to produce his line in New York, and moved to Los Angeles to access better clothing factories, Bogo thinks all designers should live in New York at some point if they can. He believes the hurdles local designers face there is what makes them stand out within the industry.

“[In New York,] it was more about the craftsmanship of it. It was not necessarily like: ‘Oh, I’m going to manufacture here,’ because it’s expensive and hectic to get stuff made in New York,” says Bogo, who is presenting in-person at New York Fashion Week for the first time this season. “I think that forces a lot of young designers there to tackle these projects by themselves, in small quanitites, without breaking the bank. People who are able to do that shine through. I think it pushes designers into the space of like: “You know, we’re going to put all our energy into making these really nice pieces.”

When it comes down to it, securing proper funding is likely the biggest challenge when it comes to building any fashion business in New York. Sadé Lewis and Shaniya Charles, the founders of the womenswear label Sadé|Shaniya, have experience working with factories in China and Sri Lanka via their 9-5 jobs in the clothing business, but they’ve still opted to produce in New York, where they’re both from. They went to the same public school in Brooklyn and graduated from FIT together in 2017. Both are well aware of how much cheaper it is to produce overseas, but they want to watch every step of the garment-making process and produce their line in New York. In an effort to save money and be more sustainable, all their clothes are made-to-order but it’s still expensive. It costs $3,500 to have six samples produced for their upcoming collection and they estimate that building out looks for a show can cost up to $10,000.

New York-based organizations like the CFDA have helped connect them to factories that are open to working with a brand of their size, and they, along with programs like the Fashion Scholarship Fund, try to aid young designers with grants. But the designers say this money isn’t always easily accessible.

“In my experience of trying to find funding outside of loans with banks or investors, the requirements exclude a lot of people,” says Lewis, who noticed that the small business grants she’s come across require brands to make $50,000-$100,000 in annual revenue or hire a certain number of employees. “Overall, I think everyone can do a better job at least offering diversity in their grants as far as requirements go and who they select.”

The CFDA is also invested in keeping the Garment District alive. Since 2013, it’s collaborated with the New York City Economic Development Corporation on the Fashion Manufacturing Initiative, a public-private program that supports and promotes the growth of small businesses in the city’s fashion and manufacturing sectors. But in 2018, the Garment District was controversially rezoned by New York City government, which removed a mandate from 1987 that required landlords in the district to preserve space for fashion industry tenants. The rezoning allows for landlords to further develop the area for office spaces rather than garment manufacturers. Simultaneously, the city has invested $136 million to build the Made in NY Campus, a modern hub for garment manufacturing, television and film scheduled to open in 2022 in Sunset Park, Brooklyn—another move that came with some controversy since it would also displace sewing factories, pattern cutters, woodworking shops, and moving companies that are already based there.

“New York is the fashion capital of America and will continue to lead the way beyond the disruption caused by the pandemic. The garment manufacturing industry is incredibly important to the fashion brands and businesses that call New York City home,” an NYC EDC spokesperson said in an email to Complex. “Fashion brands and businesses both large and small use local manufacturers to produce their runway items, manufacture small batch orders, and test ideas and concepts to go to market. This ecosystem is important to the health of the broader garment and fashion industries.”