“How Sway?!”

You probably know who said this, but do you remember the context? It was 2013. Kanye West was a frustrated guest on Sway Calloway’s SiriusXM show Sway in the Morning. By this time he’d spent his own money trying to launch Pastelle, his storied fashion brand that never came to be. And then spent even more money on a luxury women’s line, DW by Kanye West, which he renamed Kanye West, that lasted for two seasons and showed in Paris in 2011 and 2012.

He was also upset that Nike, which he signed a deal with in 2007, wasn’t giving him more room to create, so he jumped ship to Adidas in 2013. Despite that new partnership, he’s agitated during the interview and calls on bigger companies like Nike, Google, and Walt Disney to invest in Donda, his creative agency, and his ideas. Calloway played big brother during the conversation and tried to offer him a solution.

“Why don’t you empower yourself and don’t [rely on] them and do it yourself?” Sway asks.

“How Sway?!” Kanye yells before repeating the now iconic refrain: “You ain’t got the answers!” about five times. “You ain’t spend $13 million of your own money trying to empower yourself!” Kanye says. Sway counters, saying he’s spent thousands of dollars to get his clothing line off the ground, and West famously responds: “It ain’t Ralph, though. It ain’t Ralph-level. What’s the name of your clothing line? We don’t knowwwww.”

West’s argument with Calloway was focused on himself, but it told a bigger story about the financial barriers that come with starting an apparel brand, and as with most barriers, they become harder to break down when you are Black—even when you are rich, famous, and highly influential like Kanye West.

Kanye, like many, sees Ralph Lauren as the pinnacle: a more-than-50-year-old global lifestyle brand that brought in $6.16 billion in revenue in 2020. It’s a place most fashion designers don’t reach, but Ralph Lauren and his peers—Calvin Klein, Donna Karan, Tommy Hilfiger, and Michael Kors—have a few things in common: They are owned by publicly traded companies, backed by massive financial engines, and the founding designers are white. These designers no longer own their brands, but they received the support needed to scale, be acquired and/or go public—much like James Jebbia’s Supreme, which was purchased by VF Corp. in late 2020 for a reported $2.1 billion and is expected to reach sales of $500 million in 2021. They have become, and in the case of Supreme, are becoming, heritage brands and household names in a way Black designers haven’t been able to as of yet.

Ownership within the fashion business is hard for everyone, and with Black people making up 13.4 percent of the US population, it’s expected they have less ownership. But it’s hard to ignore these numbers: According to a 2019 Nielsen study, Black consumers in the US have $1.3 trillion in annual spending power and their purchases have a halo effect that influences all consumers. But according to the US Census, Black people own only 7 percent of the businesses in the US. This poses a big question: Why do Black people own so little of an ecosystem that heavily depends on them to buy and promote its products? It’s a multifaceted issue that involves a lack of knowledge, support, and control along with the fashion industry’s limited perception of Black brands.

As two Black men who own a sportswear line and have a strong grasp on production and manufacturing, Cross Colours founders Carl Jones and TJ Walker are still anomalies in the fashion business. Prior to Cross Colours, the colorful clothing brand that launched in 1989 and promoted equality, there was WilliWear, a line started by Willi Smith, a Black designer, in 1976 but mostly owned by his French business partner, Laurie Mallet. There was also Patrick Kelly, another Black designer who had to move to Paris for acceptance from the fashion community and received financial backing from Warnaco. But together, Jones and Walker opened the door for a new type of Black brand that was directly connected to hip-hop and youth culture. And to get Cross Colours up and running, it required a lot of cash.

Prior to starting Cross Colours, Jones spent a couple of years running a brand, Surf Fetish, with two Morrocan Jewish partners, and because of its success he was in a position to put up almost $500,000 of his own money to launch Cross Colours, which was influenced by a piece of kente cloth a Black salesman encouraged him to use in some way. The money went into producing samples and marketing materials, and hiring a small staff that could help with publicity and sales. Jones said because of his race, he felt an extra layer of pressure to make things perfect.

“First of all, we’re African-Americans and we’re in the fashion business. So we had to do everything better than everyone else,” says Jones, who added that the Los Angeles fashion industry at that time had very few Black people.

Along with cash, Jones and Walker had established relationships with retailers thanks to Surf Fetish, which put them in a position to present their line to Merry-Go-Round, a now defunct national clothing chain. Merry-Go-Round was looking for brands that connected to the “urban” (or Black) consumer and it bought into Cross Colours. Those orders, and Will Smith wearing Cross Colours on The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, helped them when they got to Magic, the apparel trade show in Las Vegas where stores purchase products from brands to sell in their shops. Within three days they closed $15 million in business—Jones says he left the show with orders by the pound that he packed in a piece of carry-on luggage. But he had to secure a bank to lend them $7 million to produce and ship the orders.

“We had the banks and the community behind us to help us finance it because first of all, we weren’t Black anymore. We had become green.” - Carl Jones

If you wholesale, meaning you sell your clothes to stores, you need the capital to produce samples, present them to stores, and then produce and ship the pieces the stores order. Then you need the cash to hold you over until stores actually pay for the order. And if the product doesn’t sell, they either discount it or ship it back to the brand who is responsible for selling it—this is how after-season pieces end up in TJ Maxx or Marshalls. Cross Colours closed $15 million in orders on paper, but they needed $7 million to produce and ship those orders so they could be paid. That’s where banks or factors come in. Factors loan brands a percentage of their invoice orders to produce clothes and finance day-to-day operations until retailers pay them. It’s a loan. Luckily for Jones, he had good credit, but the expenses connected with operating a fashion line make it harder for most Black people to enter the business and stay.

“As people of color, we don’t come from legacy wealth and legacy information,” says Daymond John, who co-founded FUBU with J. Alexander Martin, Keith Perrin, and Carlton Brown in 1992. John also had a unique financial advantage: His mother mortgaged her house to provide him with $100,000 in startup money for FUBU.

Beth Birkett, who co-owns Union, started Bephies Beauty Supply last year—the name acknowledges another industry, beauty supply stores, that Black people patronize but have very little ownership over. She hasn’t always observed that same type of financial support.

“I come from West Indian family. I’m Jamaican, Barbadian, and African American. I don’t want to say that most West Indian families believe in education and jobs and feasibility, but they don’t see ownership as accessible or stability,” says Birkett. “And I get it. Whenever we’ve tried to build something of our own like Black Wall Street for example, it’s been taken away from us. It’s been burned down. We’ve been killed and we fear for our lives. There’s a lot of trauma and anxiety around ownership and what that means for Black people.”

But Jones and Walker, who were operating in a sea of Jewish men who ran the LA manufacturing business, say everyone in the industry including the finance community, the fabric suppliers and the local Korean manufacturers, supported the brand because they paid their bills on time and were extremely profitable.

“We had the banks and the community behind us to help us finance it because first of all, we weren’t Black anymore. We had become green,” says Jones. “So whatever we wanted, because we were shipping millions of dollars, they gave it to us.”

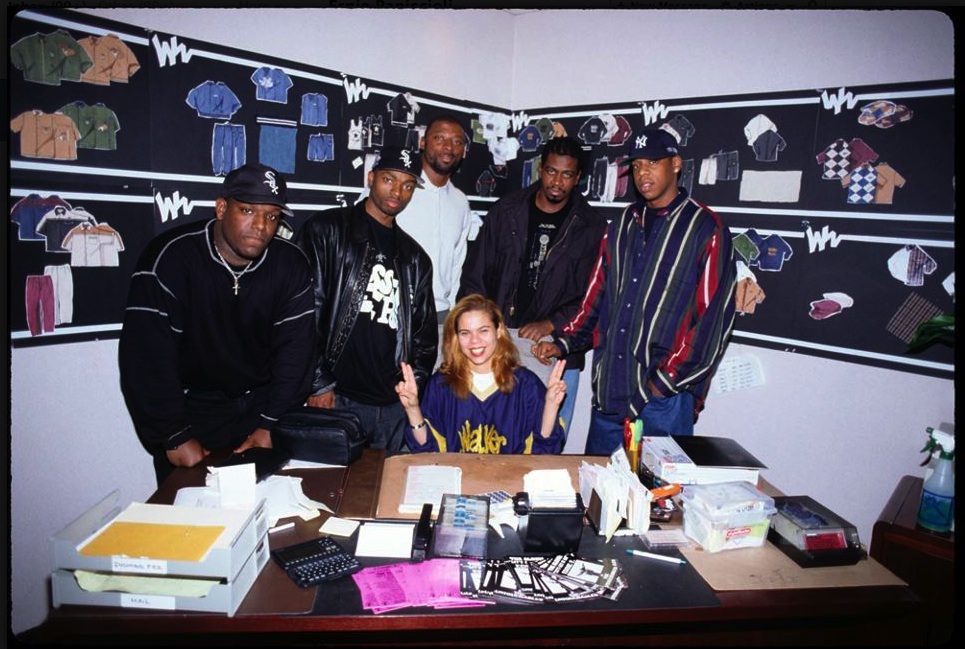

Finding a bank to loan her money wasn’t as easy for April Walker, a Mexican and Black woman from Brooklyn who was starting from scratch. She was inspired by custom designs from Dapper Dan when in 1988 she opened Fashion In Effect, her custom clothing business located on Grand Avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant. This is where she introduced her sportswear brand Walker Wear—which was influenced by WilliWear. Walker, whose father managed rappers Jaz-O and Jay-Z, was entrenched in hip-hop and making her signature Rough and Rugged denim suits (matching jacket and jeans with contrast stitching) for celebrities like Run DMC’s Jam Master Jay. So when she showed at the NAAMSB trade show at the Jacob Javits Convention Center in New York City in the early ‘90s, she walked away with $300,000 in orders, but didn’t have the capital to produce the line.

“I was green. So I thought, now that I have legitimate orders, I could get a factor, produce, and send out the clothes,” says Walker. “But being a small business and being a Black and brown woman, it didn’t work out like that. They said I wasn’t in business for three years, so I wasn’t factorable, even though I had legitimate paper from established businesses that were factorable.”

Walker produced some of the orders on her own, but traveled to Los Angeles where she built connections with factories that took on her orders. It was a similar path that Karl Kani, another Brooklyn native, took a couple of years before her. He, like Walker, had a Brooklyn shop in Flatbush, but moved out to Los Angeles because business costs were lower and clothing manufacturing was easier. Kani and his childhood friend A.Z. Johnson opened a store on Crenshaw that they also lived in, but once they were robbed they moved their operations to an apartment and started selling via mail orders in Right On! Magazine. One night Kani’s friends influenced him to go to a Cross Colours event where he met Jones and they eventually formed a 50-50 partnership under Threads 4 Life, Cross Colours’ parent company. That deal put the much needed fuel into Kani’s business, which went from selling out of his apartment via mail-in orders to being distributed across the country.

Walker Wear, Karl Kani, and Cross Colours were Black-owned fashion businesses that benefited from the times—at one point Walker was in talks to partner with Threads 4 Life, but the deal never happened. Hip-hop was a growing genre and stars including TLC, the Notorious B.I.G., and Tupac wore their clothes—Tupac appeared in one of Karl Kani’s early ads for free. And during the ‘90s, since Black consciousness and buying Black was prevalent, there was a goodwill around these brands and a desire for them to succeed. They created an authentic formula for launching Black-owned brands that spoke directly to Black people and utilized hip-hop—Kani says at the time most major brands didn’t touch rappers. The Magic tradeshow went from being a mostly white show to a space where Black brands and Black salespeople existed and they were making millions of dollars. But because these brands and the genre was so new, sometimes they had to convince buyers they were credible.

“When I first started, I remember one of the buyers telling me about my velour sweatsuits, ‘Why would I buy your velour sweatsuits for that? That’s what FILA charges for their sweatsuits. Who do you think you are?’” says Walker.

Jeff Tweedy, the executive who helped grow Sean John to be a $500 million dollar business, faced similar battles. He was fresh from building up 40 Acres and a Mule, Spike Lee’s apparel and merch brand—at one point Malcolm X merch was the second highest selling movie memorabilia after Indiana Jones. On a trip to Los Angeles he met Jones and started working for Cross Colours and then Karl Kani. Part of his job was to persuade the banks and retailers that Black brands were legitimate. For example, he had to push Macy’s to not only sell Karl Kani in its Brooklyn shops but also its Herald Square flagship in Manhattan.

“Karl Kani was a $250 million brand, and even then I had to have serious conversations with department stores in the States because they dismissed us as being some ghetto, urban streetwear. But when it came to Aaliyah wearing Tommy Hilfiger, it was shining armor,” says Tweedy—Aaliyah wore Karl Kani on the cover of her 1994 debut album Age Ain’t Nothing But a Number and appeared in a Karl Kani ad. “Retail doesn’t embrace longevity of the culture and respect the customer. They still think that they don’t have a Black customer walking into certain stores, even to this day.”

Before e-commerce, Black brands relied on wholesale. In many ways they were at the mercy of buyers, which put them in a precarious position. It’s what contributed to the demise of Cross Colours, which was doing about 80 percent of its business through the retail clothing chain Merry-Go-Round—Jones says sometimes they were selling $10 million worth of product in its stores a month—but once the store went out of business and canceled the orders, Jones and Walker were forced to sell off all their inventory and even loan their trademark to a well known company while they got their finances in order. And once they did, this corporation, who Jones didn’t want to name, refused to give them their trademark back.

“We grew too fast, too quickly,” says Jones, who remembers a particular time when Merry-Go-Round faxed him about 15 orders within 20 minutes worth $9 million. “And I’m like, ‘What do you want me to do with this?’ And they responded, ‘I want you to go and make it.’ So I did. We had become a big part of their business and the more they sold, the more they wanted to buy. So what did I do? Maybe stupidly, I go and make it.”

Despite department stores buying deeply into these brands, Kani says they didn’t offer them the same level of protection or sometimes promotion as larger companies like Ralph Lauren.

“The game was all about real estate. Whichever companies have the most real estate in stores are the companies that are going to work. Those are companies that no matter how bad your season is they’ll continue to push the stuff,” says Kani, who heard certain lines didn’t want to sit next to his despite how well it was doing. “So you go to Macy’s, who owns all the real estate? Ralph, Tommy, Calvin, Donna, the same names, the usual suspects. Those are the ones that have all that floor space with the big shops. So you know what? If Ralph has a bad spring season, Macy’s ain’t kicking them out. They’re going to make it work. They’re going to figure it out. As streetwear designers, you have one bad season, you’re out of there.”

Placement aside, moving into larger department stores opened up the market for other urban brands like Maurice Malone, Phat Farm, FUBU, Sean John, Rocawear, Mecca, Enyce, Ecko, and others. Magic went from having two or three urban brands to an entire section dedicated to the category. It was a category that buyers could easily understand and therefore place in their stores, but it wasn’t always a category Black-owned brands understood. And for some of them, it was limiting.

Kimora Lee Simmons started Baby Phat in 1999. It was the women’s companion to Phat Farm, but positioned as more aspirational. Simmons, who is Black and Japanese, appeared in its ads with her daughters and put on extravagant fashion shows and after-parties during New York Fashion Week. Simmons says the consumers and press immediately understood her and her brand, which pushed for diversity and multiculturalism before it was a trend. But she says buyers were less clear about her vision.

“There were people who would say, ‘Oh, which floor are you on? How did you get to this floor? What floor did we put you on? Oh, that’s urban.’ You know, the same conversation you always have. Those were the people who seemed a little confused,” says Simmons.

When asked if she liked the urban label, Simmons says she didn’t dislike it, she just never fully understood what it meant: “Is it a location where you live, or is it like an abbreviation for sub-urban? Is sub-urban? I don’t know. Nowadays, it looks to me like streetwear. But is that what it means? Streetwear in the streets, casualwear? I didn’t understand. Is it a skin tone? Is it a color? Is it Black people? Is it a movement? What is it? I just knew that I kept getting tossed around in that box, and I’m OK with that. I just want to know what other boxes I can jump into too since you put me in this one, because I need a wide playing field.”

Scott Sasso, who worked for Akademiks during the ‘90s, but would later launch 10.Deep, says Black brands were expected to fit into a formulaic mold and they lost creative autonomy.

“It was becoming too boxed. There are too many rules. People were like ‘Yo, your jeans, you can’t fit $5 in the pockets of those jeans.’ I’m like, ‘What? What are we talking about here? We’ve all got to dress exactly alike? We all got to behave this one way?’ That’s not me and fuck you to tell me how I’m supposed to behave,” says Sasso. “It was kind of like all the brands had a formula. ‘Oh, we’re going to do sweatsuits with the stripe down the side and it’s going to have the number on the left chest and arch type going across over here.’ And as soon as that happens, then how is that interesting?”

But on a commercial level, the formula was working. In 2003 urban-apparel sales reached $6 billion, and corporations started to invest in or back these brands. Karl Kani signed a joint venture deal with Skechers that helped buy him out of his situation with Cross Colours, covered his manufacturing for Karl Kani footwear, provided him capital, and owned part of the profits. Skechers was slated to go public but Kani wanted to retain ownership of his trademark and said Skechers only offered him royalties, not shares, so he got out of the deal. FUBU partnered with Samsung, which handled manufacturing and distribution but the founders maintained ownership.

But once the acquisitions in the space happened, and celebrities started to cash in, Black ownership within the space decreased. In 2004 Kellwood acquired Phat Fashions, which included Phat Farm and Baby Phat, for $140 million. Liz Claiborne bought Enyce in 2004 for $114 million. And in 2007 Iconix purchased Rocawear for $204 million in cash. PNB Nation, a brand that merged skating, graffiti, hip-hop, and socially conscious messages, got in and out of a few licensing deals before selling to American Dream Team Network in 2002. Co-founder Zulu Williams says once the brand got into a larger corporation’s hands, it changed.

“I kind of felt like we were being something that we were not,” says Williams. “You’re struggling because on the one hand there’s art, and on the other there’s commerce and you have to balance the two. In the early days it was about the art, and then as we did these licensing deals it became more about commerce and making sales. I don’t know if it’s dumbing it down, but we definitely went more branded as opposed to social commentary.”

Once corporations got to them, many of the urban brands oversaturated the market and started to become less popular. While Black designers and brand owners got rich, most didn’t retain much ownership. Rasheed Young, a business development consultant and serial entrepreneur who started Pastry sneakers with Vanessa and Angela Simmons, was there to watch the transition. He created Run Athletics, an apparel and sneaker brand, with Russell Simmons and Rev Run right as Kellwood started to license Phat Farm and before they purchased it. Phat Farm was approaching 10 years in business and the marketing was growing up, leaning into “Classic Americana” concepts. Young says this was during Jay-Z’s button-up era. He believes Simmons selling the brand at that time made sense.

“That was a brilliant idea, to be honest. Two years after he sold, the brand tanked. He got out on top if you will,” says Young, who now co-owns Park Madison, a line started by Raymond Santana, one of the Exonerated Five. But Young also believes long-term ownership isn’t rooted in Black culture. “We think we want to be Ralph Lauren, but I don’t think that’s in our DNA,” he says. “We are lacking long term vision and chasing instant gratification attached to a mild glimpse of success and pocket change.”

James Whitner, who solely owns The Whitaker Grp, a retail network made up of 17 locations across the US, says greed led to the demise of the urban category, which in 2004 was generating $10 billion in sales.

“They failed because they kept chasing millions. They kept chasing more, more, more. Now, everybody looks at demand planning and undershoots their business. So if you know there’s $100 in the market, you only fulfill 5 percent of the market,” says Whitner. This is one of the reasons why Supreme has been able to sustain and grow over the course of almost 30 years. “And listen we all can’t be expected to be the same, right? You can’t be mad at somebody for taking the money. But then we can’t be mad when we don’t have any Black brands long term.”

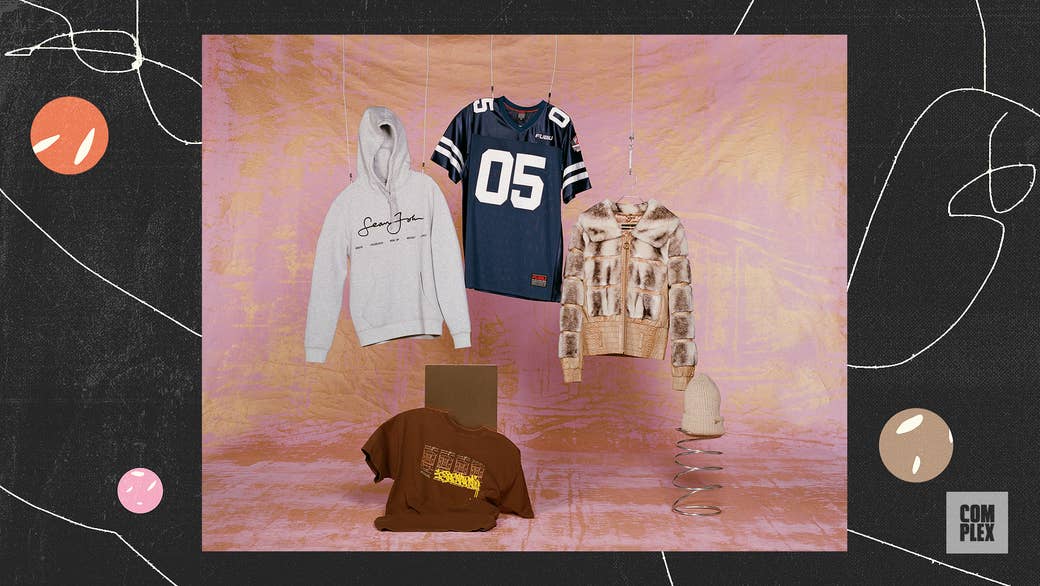

Sean John was in a different position. In 1998, Sean “Puffy” Combs received a $50 million advance from Arista and used some of that to start Sean John and hire Tweedy. Tweedy says Combs had ambitions to be a true lifestyle line and a $100 million company, so they partnered with the Sani family to handle manufacturing and distribution. Tweedy says their strategy was to capture the young man who was starting in a management position at his job or buying his first home or luxury vehicle and had a family. He was growing up and didn’t want to wear big logos anymore.

But Tweedy knew that in order to change perception—that same perception that boxed Black brands into the urban category—Combs would have to ingratiate himself in the fashion industry by attending fashion shows, going to lunch with main players in the industry, and putting on big, entertaining shows at New York Fashion Week—although Tweedy says they only produced about 20 percent of what they showed on the runway. Combs fought against the hip-hop and celebrity brand labels, telling Fortune magazine in 1998, “My clothes are not about marketing to hip-hoppers. They’re about marketing to Generation X, whether they’re white, Black, Irish, or Latino.”

And the strategy was successful. Combs was the first Black designer to receive the CFDA Men’s Designer of the Year award for Sean John—he was up against Ralph Lauren and Michael Kors—and the line was picked up by Atrium and Bloomingdale’s. Hip-hop always had a connection to luxury brands, but often times those brands didn’t acknowledge hip-hop. Sean John was almost a response to that. The line also attracted investors. In 2003, billionaire Ron Burkle, the managing partner of The Yucaipa Cos., a private equity firm based in Los Angeles, invested $100 million into Sean John. Tweedy says Burkle was strictly an investor, and Combs still retained majority ownership of the company. He used that investment to form a 50-50 joint venture with Zac Posen and in 2008 he purchased Enyce for $20 million.

Post 2005, the urban category was mostly done and streetwear emerged. It was a category informed by urban apparel, but had a different scope. It was brands like The Hundreds, Crooks & Castles, Staple Pigeon, Mishka, LRG, Diamond Supply Co., and A Bathing Ape. Brands that touched on hip-hop, graffiti, skate, surf, and other subcultures, but with the exception of Pharrell’s Billionaire Boys Club and Icecream and Sasso’s 10.Deep, they didn’t come from Black designers or founders. Hip-hop still embraced it. Kanye West frequently wore LRG and appeared in its ads. Jay-Z wearing a Crooks & Castles T-shirt helped jumpstart the brand. And Pharrell popularized BAPE in the US market—initially BAPE’s founder Nigo produced the BBC and Icecream lines in Japan before Jay-Z’s Roc Apparel Group, which was under Iconix, purchased a 50 percent stake in the business for $3.5 million in 2012. Financially this category blew up, and the spending dollars that went toward urban filtered into streetwear. In 2006 for example, LRG’s annual revenue was $150 million.

“The backers paid attention to the business and then started phasing out the faces of the brand and just said, ‘Let the product speak for itself,’” says Walker. “It gave them a leg up and once streetwear emerged it was like, ‘Now we don’t need you as the face of the brand. We figured out the formula, we have the machines and it’s no longer about Black people.’”

“Retail doesn’t embrace longevity of the culture and respect the customer. They still think that they don’t have a Black customer walking into certain stores, even to this day.” - Jeff Tweedy

After the 2008 recession, Sean John shifted its identity from what Tweedy called “me to we,” and it became less ostentatious and more mass to adapt to the times. In 2010 the brand signed a deal to be exclusively distributed through Macy’s, but retained majority ownership until 2016. Combs’ strategy shifted, but his efforts helped open a door for for Black brands (and celebrities) who wanted to be positioned in an elevated way and not only be considered “urban.” Sean John alumni, Dao-Yi Chow, who is Chinese, and Maxwell Osborne, who is Black, benefited from that when they launched Public School in 2008, won a CFDA Swarovski Award for Menswear in June 2013, and held a short stint as creative directors of DKNY in 2015.

Shayne Oliver, who co-founded Hood By Air in 2006 with Raul Lopez, also wanted to close the so-called gap between urban and luxury design and Hood By Air made it ok for pieces typically associated with the streetwear and urban categories, hoodies and T-shirts, to be considered investment pieces and sit alongside more progressive items. Oliver and his business partner Leilah Weinraub turned down outside investment but they did start working with The New Guards Group, a luxury manufacturer and distribution company based in Milan. The New Guards Group helped scale the brand, but in a way Oliver wasn’t comfortable with, so he got out of the deal and retained ownership in 2016. He’s now receiving financial help from Edison Chen on Hood By Air.

Virgil Abloh, who met Davide De Giglio, co-founder of the New Guards Group, through Kanye West, also partnered with the Italian company to produce Off-White. Heron Preston followed. For Abloh, he owns the Off-White trademark, which is akin to a musician’s masters, but the New Guards Group has the rights to license Off-White products and share in its profits. But like the issue Kani ran into with Skechers, it isn’t clear if Abloh had any equity in the New Guards Group, which was able to sell to Farfetch for $675 million in 2019 in large part due to Off-White’s popularity.

The fashion landscape is very different now for Black-owned streetwear brands. Unlike their predecessors, these designers have room to produce outside of the confines of streetwear, a label many of them fight against in the same way Combs rejected it almost 20 years prior. And instead of relying on their own line, there are multiple ways for them to pad their income through design jobs and brand partnerships while maintaining some sort of ownership. Tremaine Emory, the founder of Denim Tears, says the work all of these Black designers put in has contributed to this current state.

“I’m not out here creating shit out of thin air,” says Emory. “I’m very influenced by FUBU, Karl Kani, Willi Smith, all these guys. FUBU and them kind of opened the door up. Puffy walked through that door. And what Ye and P did with Marc Jacobs, that kicked the door off its hinges.”

Abloh produces shoes and apparel with Nike and collaborates with multiple corporations via Off-White. He’s also the artistic director of Louis Vuitton Men’s. Jerry Lorenzo owns Fear of God, a luxury brand, his more affordable Essentials line, and recently announced he will be launching Fear of God Athletics through Adidas. He will also head up its basketball division. And just as Kani utilized Skechers to get him out of his deal with Cross Colours, Kerby Jean-Raymond of Pyer Moss was able to buy back complete ownership of Pyer Moss from a former business partner once he signed with Reebok, where he is currently a creative director. Jean-Raymond also formed a deal with Kering, a luxury conglomerate, on a yet-to-be disclosed platform called “Your Friends in New York.” They are all smartly utilizing larger corporations to lift their profile and still maintain their own brands and equity.

Black-owned brands today also don’t have to rely on retailers like Macy’s for distribution or media outlets for press and advertisements. Thanks to the internet and social media, brands like FTP, Tier, Bricks & Wood, Midwest Kids, Darryl Brown, Barriers, The Good Company, and Joe Freshgoods are mostly selling direct to consumers and therefore able to control their margins, make a profit, and only supply what the market demands.

Joseph “Joe Freshgoods” Robinson, started out wholesaling to retailers when he started Don’t Be Mad in the early 2010s, but realized it made more sense to drop product at Fat Tiger Workshop, the Chicago store he co-owns with Terrell Jones and Vic Lloyd, or his own e-commerce site. He’s also known for releasing product in pop-ups throughout the country. Robinson has mostly stayed in the realm of T-shirts, which are cheaper to produce, but instead of taking on an investor or giving up equity, he’s used larger collaborations to move into ready-to-wear, extend his distribution, and increase production. He says his partnership with Converse was the first time his product was so accessible and available globally. He asked for less money up front so he could have more control, which is how he had a two-week window to drop the Converse collab in Chicago first and dictate the boutiques he wanted to sell the collection in later.

“There’s an art to how you scale. A lot of things are more direct to consumer, so why am I pushing people to go shop on Saks and they’re getting a percentage when I could just tell those same people to shop with me?” says Robinson, who also works with New Era and New Balance. “I’m working with Converse to elevate my brand because I’ve seen so many brands think with the wallet first instead of their heart and they’re not around anymore because they’re in Urban Outfitters for $5.”

Darryl Brown, who also runs Midwest Kids, wants his eponymous line to compete with other workwear brands like Carhartt, Dickies, and Ben Davis and says he’s turned down offers from investors because he wants full creative control.

‘’I’m 100 percent owned by me. I have some debt, but I’m just moving full steam ahead,” says Brown. “I don’t want somebody to just come wave a dollar in front of me, and think they can just have 60 percent or majority stake of my company, and then I’m working for them and have to get approval for stuff like that. I’m just not really into that.”

On the other hand, Anwar Carrots, the founder of Carrots by Anwar Carrots who owns the majority of his brand but not all of it, has a different outlook. He wants to be “the Martha Stewart and Nigo of this whole game,” meaning he wants to be a mass lifestyle brand, and he has no qualms about giving up ownership and he doesn’t view it as “selling out.”

“I don’t care about owning 100 percent of my shit,” says Carrots, who started his line in 2014. “I want to be best friends with Target and I’d be a dumbass to turn down some bread that could put me in a position to be that person. And it’s a risk, but if it did fail at least I got the opportunity to gain this money and see if it works out. Man, I’m from Trenton, New Jersey, bro. I don’t know if you know many people from Trenton, New Jersey, but if somebody gives me the money, I’m taking it.”

And right now, there are a lot of opportunities up for grabs. Following George Floyd and Breonna Taylor’s murders, Black ownership has turned into a buzzword, with the press making lists of Black-owned brands, retailers scrambling to sell their product, and brands wanting to collaborate with Black designers and artists. Jones and Walker say now buyers are asking if their brand is majority Black-owned, a question that has never come up before, and dedicating more budget to carrying these designers.

“I definitely felt a shift,” says Kacey Lynch of Bricks & Wood. “Our numbers did jump and I will say in complete transparency that it was unfortunate. But if I have to be honest with myself as a Black man, I don’t get these opportunities all the time so we’ve got to capitalize on them.”

This new attention has impacted sales in a positive way and given many of these brands more leverage, but for Shannon Maldonado, who runs Yowie, a home and life shop in Philadelphia that also produces branded product, that has meant turning down collaborations that don’t feel right and protecting her IP.

“Are you just going to slap David Hammons and Marcus Garvey’s flag on this and make some money, or you going to help Black voters matter?” - Tremaine Emory

“Before last year, I was very afraid to say no. A lot of things are presented to you like, ‘This is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. If you say no, we’re not coming back,’” says Maldonado. “But so many things just felt like thinly veiled tokenism and I turned down a lot of stuff. I’m very proud of the brand I’ve built. I work really hard every day on it. I don’t have to give that away to anyone that doesn’t feel like a partner that respects us or wants to work with us for the wrong reasons.”

Emory also said no in June when he told Converse via Instagram to not release his Chuck 70 sneaker, which was covered in Jamaican political activist and Black nationalist Marcus Garvey’s Pan-African flag and artist David Hammons’ “African-American Flag” artwork from 1990, unless they were more intentional about putting money toward encouraging people to get out and vote in such a critical election. Converse supported it by working with For Freedoms, a platform founded by artists Hank Willis Thomas and Eric Gottesman that uses art to push political awareness, on a campaign called “The Future Is Yours. Vote.”

“It’s like the Bee Gees song. ‘How deep is your love, how deep is your love, I really need to know.’ Are you just going to slap David Hammons and Marcus Garvey’s flag on this and make some money, or you going to help Black voters matter?” says Emory. “I also wanted to show people you can speak out and it’s OK, you’re still going to figure out how to pay for your rent, you’re still going to eat. Whether Converse would’ve dropped me or not, it doesn’t matter. What matters is talking about this thing. We can put all sorts of bullshit on Instagram, but let’s put some real shit up.”

Other designers like Nigeria Ealey, who co-founded Tier, a Brooklyn-based streetwear brand alongside Victor James and Esaïe Jean-Simon, just hope that this recent surge in support of Black-owned brands isn’t simply something that’s performative.

“People should be able to support us because they recognize our work and what we do and our talents and our morals and what we stand for,” says Ealey. “We want to be able to love and explore and design and create freely without the notion of, ‘let me only support because you’re a Black-owned brand.’”

Being a Black-owned brand in 2021 does come with a new set of advantages that didn’t always exist, but there are still specific challenges they face. Whitner says that now, because all brands are vying for the Black dollar, there’s more competition, which would make it harder for these brands to do sales in the same way Rocawear or Sean John did. And as one of the few Black retailers in streetwear, luxury, and sneakers, even with a fleet of 17 succesful stores, he still has to fight for brands to pay him attention.

Most of the designers also brought up how much criticism they receive from Black consumers. Birkett says she frequently sees comments with customers complaining about how expensive Black brands are, but most don’t understand that these prices exist to ensure the Black and Brown people who are making them earn a livable wage. Robinson, who is active on Twitter, also observes the criticisms and says he’s had to develop a thicker skin.

“As much as we want to bring Black brands up, we also criticize them and penalize them for every little small thing they do,” says Robinson, who remembers the backlash Telfar received on Black Twitter when people weren’t able to purchase his popular shopping bag because the site crashed. “So it’s just like we kind of got to move a little differently. We got to explain everything.”

Birkett also believes Black celebrities endorsing more Black brands could help, and now more than ever they need to be more intentional about who they support and promote.

“It really bothers me when rappers put brands in their song and I know they didn’t get paid that much money, if any, to promote these brands. And I know that if I ask them to sing a song about my brand, they would say ‘no’ or charge me a shit ton of money,” says Birkett. “That’s so irresponsible, but it’s become a huge part of our culture.”

It’s been seven years since Kanye disagreed with Calloway, and things are much different. Now he has a bigger slice of the pie. He has a licensing deal with Adidas for Yeezy through 2026, but he owns the Yeezy brand and its trademark. According to Forbes, Kanye receives a 15 percent royalty on wholesale, which Nike refused to give him, and a marketing fee, and his sneakers did $1.3 billion in sales in 2019. This past July marked another watershed moment for Kanye when he signed a 10-year deal with the Gap for a Yeezy Gap apparel line. He will receive royalties but also the option to acquire up to 8.5 million shares of common stock from Gap if his line meets certain sales targets, which means he will have equity in Gap. Now, for good reason, he’s fighting for a seat on the board.

After going through the trials and tribulations of the fashion business, some of the OGs have reentered the market in a new way. Jones and Walker bought back the Cross Colours trademark and say they are doing very well. They create licensed products with artists like Aaliyah, Left Eye, TBoz, and Tupac, and are selling in retailers including Bloomingdale’s, Zumiez, and Foot Locker. April Walker owns her company. She got out of the business but reentered and recently introduced a RAW denim campaign highlighting Black stylists. Karl Kani still owns his brand and sells product through his own site and works with Snipes, one of the largest sneaker and streetwear retailers in Europe, on international distribution. FUBU’s founders also own their brand and recently announced a new licensing agreement with The Brand Liaison, but they are focused on direct-to-consumer drops. And like Kani, they do a lot of business internationally through licensing.

For celebrities who gave up ownership, they’ve run into legal issues. After several lawsuits against each other, Iconix, which owns Rocawear, and Jay-Z settled in 2019 with the artist having to buy back $15 million worth of intellectual property in 2019 in order to keep producing the Rocnation hats. And Combs recently sued Global Brands Group, which purchased Sean John from him, for $25 million because they used his image, likeness, and persona to promote a collaboration with women’s clothing retailer Missguided that he didn’t approve of.

“I don’t care about owning 100 percent of my sh*t.” - Anwar Carrots

As for Kimora, who recalls a time when Baby Phat was producing everything from sneakers to bed sheets to cell phones, Kellwood reportedly fired her from the brand she created in 2010, but she recently bought back the licensing. In 2019 she relaunched Baby Phat via a Forever 21 collaboration that debuted with a campaign featuring her daughters, Ming and Aoki Lee Simmons, who used to accompany her down the Baby Phat runway for the final walk, and the late Kim Porter and Combs’ twin daughters Jessie and D’Lila Combs. It’s a different vibe. Instead of stepping out of a private jet as a fictional First Lady or posing on her mansion’s staircase alongside two maids, they are in skating rink. It’s girly and glamourous but less aspirational and a full circle moment for Kimora, who says she wants to pass down Baby Phat to her daughters. But she describes running Baby Phat independently as a whole new world. She just dropped a collection of costume jewelry and she’s learning more about selling online, being prudent about production, tracking her product amidst a pandemic, and juggling all of that while being a mother of five. When asked if there can ever be a Black-owned or led equivalent of a Ralph Lauren, she ponders the question, trying to make sure that one doesn’t already exist.

“I don’t know,” she says and pauses again. “I think it’s just tough to get a seat at the table. Or maybe it’s how we’re perceived. I’m not really sure. Because I’m on the inside looking out, so I really wouldn’t know. But I swear to God, I ask myself that every day. And I feel like I’m going to try to do that. So, then yes. I think the answer’s yes.”

Additional reporting from Mike DeStefano and Lei Takanashi.