Javin DeLaurier’s heart was pounding.

Halfway through the third quarter he got pulled from the court for what seemed like no reason at all. Up to that point he had five points, seven rebounds, and his Wisconsin Herd were trailing the South Bay Lakers by double figures inside the Mandalay Bay Convention Centre in Las Vegas six days before Christmas.

The 23-year old forward just got told the Milwaukee Bucks were thinking about signing him.

“It seemed like something was starting to shake up a bit,” he said. “I wasn’t sure what was really happening.”

The Herd won the final quarter by six, but lowered their colours to the Lakers 119-112. As soon as the match wrapped up, DeLaurier was on the phone to his agent Gary Durrant who confirmed that the Bucks were considering offering him a 10-day contract after a wave of NBA players had tested positive to COVID-19—more than 100 players have taken 10-day contracts since December.

DeLaurier left the arena and took the overnight flight from Las Vegas to Milwaukee and was told if enough people test positive they would use one of their hardship spots to sign him. When he landed in the morning he was told the entire roster had tested negative. That day, DeLaurier flew to Virginia to see family. When he was walking through the terminal at Charlottesville Airport, Durrant rang him to say he was booked on the 6 a.m. flight to meet the Bucks in Dallas.

It wasn’t that long ago that DeLaurier graduated from Duke University, majoring in international comparative studies, and spent four years in a role-playing situation that gave him limited touches. The 6-foot-10 big was a kid on the fringe who went undrafted in the 2020 NBA Draft and hadn’t unlocked his full potential. Now he’s become the first Canadian Elite Basketball League (CEBL) player to earn an NBA contract, realizing a dream he’s had since he was in high school.

“It was a pretty crazy turn of events. One that I just keep feeling extremely blessed throughout this whole process,” DeLaurier told Complex Canada. “It’s a powerful realization when you look back and see how far you’ve come. Things have moved along more rapidly recently but you know this is something I’ve been pursuing ever since I started picking up a ball.”

DeLaurier grew upon a sixth-generation cattle farm in Shipman, Virginia, a small town nestled inside Nelson County that has less than 500 people. On the 600-acre property where his Native American ancestors lived hundreds of years ago, he developed a relentless work ethic in all kinds of weather and on countless holidays. His mother, C’ta, who raised four boys, says he shouldered a lot of the responsibility early on. It’s there he learned how to nurture horses in the paddock, corral cows in the mountains, and mend barbed wire fences.

“For a long time Javin was convinced he’d be a jockey,” C’ta said, laughing. “There are no days off. Javin really learned what hard work meant.”

When DeLaurier was 18 months old, C’ta recalls, all he wanted to do was throw and catch the football. They would spend time practicing on the property where she would yell, “Hike! Hike! Hike!” and he’d sprint and catch a Hail Mary. From a young age, DeLaurier displayed the type of athleticism that made him an all-round threat in any sport. Baseball was his first love. But when he started to pick up a basketball, C’ta said her son reminded her of a young Scottie Pippen.

“Irrespectful of any sport he would probably be successful at it,” she said. “Part of that is his DNA. Part of that is also his character.”

At 15, DeLaurier remembers that’s when he caught the hoops bug. That’s when the seed was planted and the NBA dream became a vision. In freshman year at St.Anne’s-Belfield, he hit a growth spurt and went from five-foot-10 to six-foot-five. He started daily gym workouts. He was the guy dribbling the basketball down the hallways in between classes and when he got spare time he’d be on the court putting up shots emulating his idols: attacking the offensive rim like Giannis and defending like Kawhi.

Ty White, DeLaurier’s AAU coach at Team Loaded, whose job was to recruit basketball talent in the Virginia region to play at the elite level for high school kids, first met the Nelson County native in sophomore year. White recalls immediately seeing a kid with raw talent who had long arms, a great motor, and was extremely athletic. He could run the floor and had a high IQ, but like most teenagers, still needed to add size.

“He was still figuring it all out but he always had a passion to get better,” White said. “He was a relentless worker.”

During that sophomore year at St.Anne’s-Belfield DeLaurier started to get some attention averaging 11.7 points and 12.7 rebounds with three blocks a game. By senior year he was dominating games with 21.9 points, 12.9 rebounds, four assists, and three blocks per game. C’ta still remembers what the sacrifice looked like. Days would start at 6:30 a.m. and sometimes end at 9 p.m. School was an hour north of the farm and then there were weekend tournaments often three hours away.

But the family—DeLaurier’s grandparents Brad and Wisteria, his father Jason, brothers Ethan, 18, Eli, 16, Jack, 10, and Deanna, his aunt—never missed watching basketball games and C’ta says, “where Javin or any of our kids go, we all go.”

As a teenager, everything DeLaurier did was all about improving his game. White said he became the standard other kids looked up to.

“He showed up every day with his hard hat on. He did use his voice to lead, especially when he got into comfortable situations but he was the one that led by example first,” White said. “He just hated to lose. He had this will and desire to win and losing was never an option for him.”

DeLaurier often flew under the radar in regional tournaments. White remembers when he used to play against the calibre of Bam Adebayo and Dennis Smith Jr. and no one knew who he was. By the end of the competition, which White called “epic wars,” he had earned their respect because of how hard he competed.

“He was one of those guys where you didn’t know his name going in but you definitely knew his name going out,” said White.

In the Fall of 2015, out of six schools including Notre Dame, Arizona, Stanford, and Texas, DeLaurier committed to Duke University with a scholarship offer, at the same time as Jayson Tatum. He left high school as a four-star talent, All Central Virginia Player of the Year, was ranked by Scout.com as the ninth best power forward in his recruiting class and 40th overall prospect.

“The NBA for any kid, whoever really dribbles a ball, and has aspirations to play, I think that’s the goal and that’s the dream at some point,” DeLaurier said. “I knew after a couple of years I had a chance if I just continued to work.”

When DeLaurier arrived in Dallas he had to pass a physical, pass a COVID-19 test, and then it was business as usual. Given that the Wisconsin Herd’s style of play and how they run their team is modelled after the Bucks, it made things easier for DeLaurier to stick to his routines.

He knew a lot of the faces thanks to a training camp stint this year in Milwaukee for a month where he got to absorb the routines of a championship team through the lens of Jrue Holiday, Bobby Portis, Kris Middleton, and Giannis. He referred to them as “humble stars.” One day after practice, Giannis came up to him to introduce himself and asked what size shoe he wears. As it turned out, they are both size 16 and Giannis gave him eight pairs of his Freak 3s and Freak 2s.

On New Year’s day, when the Bucks beat the Pelicans 136-113, DeLaurier logged his first NBA minutes. In three minutes he accumulated his first NBA stats with one rebound, one steal, and a personal foul. The numbers weren’t eye-popping but DeLaurier was living his childhood dream.

“You’re going to have naysayers, doubters. For me it wasn’t so much proving everyone else wrong as it was proving myself right.”

The path to here wasn’t a straight slingshot.

When DeLaurier graduated from Duke, the global pandemic forced the NBA to shut down. Teams couldn’t invite draftees to train with them. Players had to isolate and resort to work outs in rooms and apartments. Durrant says the opportunities were limited and he didn’t really know what to expect.

“We’ve never had a time like this where teams aren’t able to bring guys in to work them out. He came out at a very difficult and uncertain time,” he said. “Jav hadn’t lost his optimism. He was eager to get closer to his goal and find out what he’s got to do to get to the NBA.”

The lack of opportunity was one of the reasons DeLaurier went undrafted in the NBA in 2020. It was two-fold: He didn’t get a chance to showcase his skill set in front of teams but also his Duke numbers weren’t flashy.

In his four years there he averaged 3.4 points and 3.8 rebounds in 13.4 minutes. He was competing for time against star quality talent in Jayson Tatum, Zion Williamson, RJ Barrett, and Marvin Bagley, which reads like some kind of All-Star college roster. But through those years—two of those he served as the team’s captain—he never stopped believing in himself.

“You’re going to have naysayers, doubters. For me it wasn’t so much proving everyone else wrong as it was proving myself right,” DeLaurier said. “I had more in the tank to show. In terms of doubting myself, that was never the case. I played with some really talented players and wasn’t able to showcase all of my talents all of the time.”

When Niagara River Lions head coach Victor Raso and newly appointed co-general manager and head of basketball operations Antwi Atuahene were looking to sign imports and put together a roster that could win a championship, DeLaurier’s name was on the table.

Atuahene saw DeLaurier as someone that could compete, be aggressive at the rim, and run the floor. He was confident that he had a high ceiling and was yet to unlock his full potential. He’ll tell you he saw the next Clint Capela—only with a better IQ. With limited film from Duke, they only had gut feels to go by. But it only took until the second day of training camp where DeLaurier blew away Coach Raso and Atuahene by showing them things they didn’t see on film, like breaking away in transition and using his length.

“Not making it to the NBA after being a captain at Duke, I think maybe Javin felt like people lost hope in him. I think Javin wanted to reassure people around him and himself that he never lost hope in himself and wanted to prove to himself that he can make it to the NBA,” said Atuahene. “I said, This guy is an NBA player.’ I want to get this guy in because I think we can help him grow.”

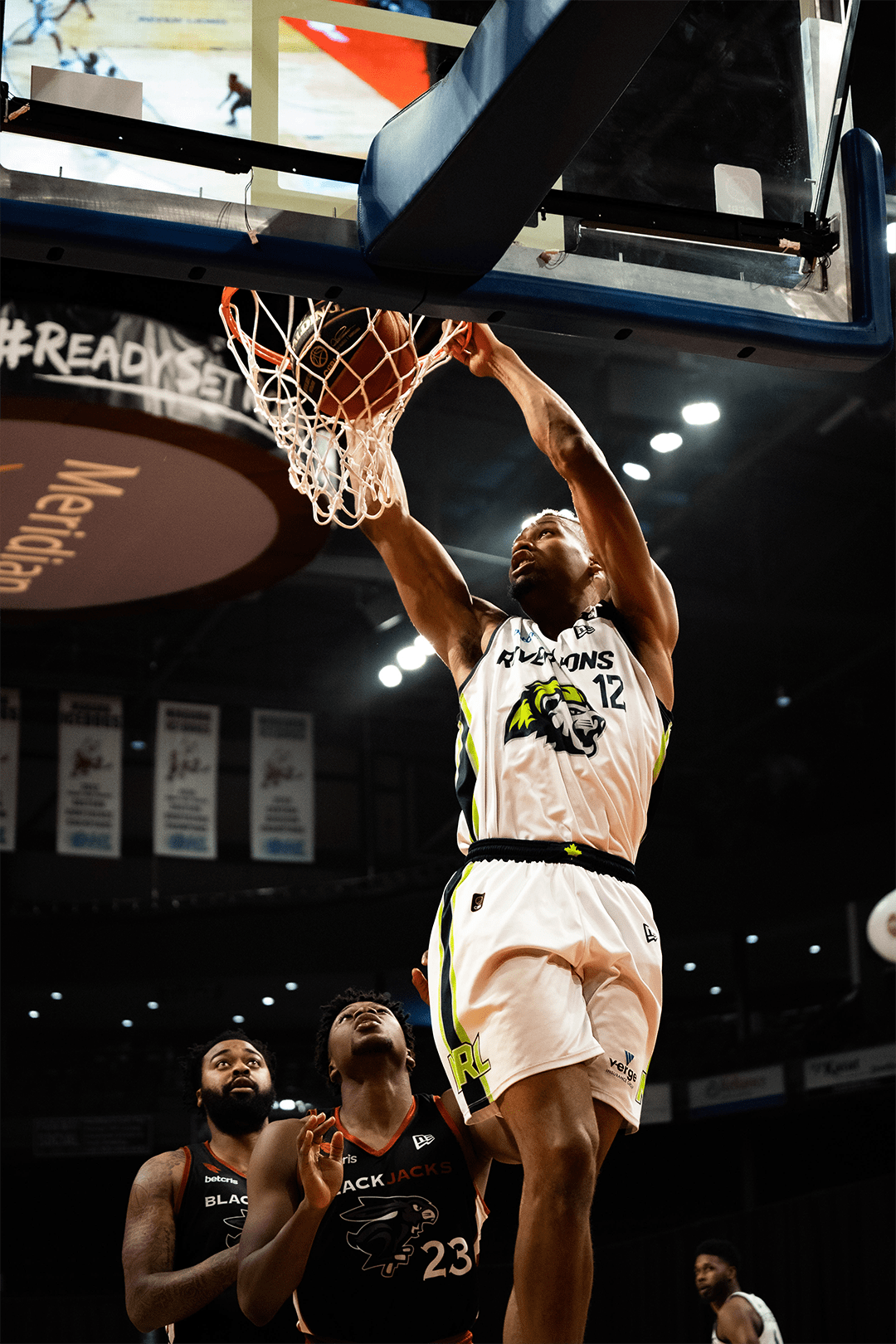

In 11 games he played with the River Lions he averaged 26 minutes, 14.8 points, and 10.4 rebounds per game, shooting at 52.4 percent from the field. He became an integral part of the team as a dominant big. He helped propel the River Lions to a 10-4 finish, eventually losing in the final 101-65 to the Edmonton Stingers.

DeLaurier made the All-CEBL first team as a starting forward and exploded on the stats sheet in games like the 17 points and 17 rebounds he laid out in a 71-68 come-from-behind victory over the Hamilton Honey Badgers. He joined the Atlanta Hawks for Summer League and Milwaukee Bucks in the pre-season. And he suited up for the Wisconsin Herd from the G League. It was like DeLaurier was speed dating his way through the basketball circuit and with each experience his confidence grew. Others finally started to see him as the NBA hopeful he always thought he was.

Coach Raso says during their time together he saw a renewed sense in himself that he can play basketball at the highest level. Along with upside and growth there were also times where DeLaurier got sent to the bench for sloppy plays, or lethargic efforts, or scolded for not hitting targets that were expected of him. And sometimes Coach Raso reminded him of things like, “NBA bigs don’t have soft takes around the rim, they dunk it,” as motivation for where he needed to be.

“We spoke to him as if we were speaking to someone who we believed should be in the NBA. And Javin, he was so drawn to that,” said Coach Raso. “His skills can improve. He needs to add some more size. But he fits the bill for a modern-day NBA five man. He runs like a deer. Has long arms. Can catch lobs. Sets solid screens. Blocks shots at the rim. That is what a lot of NBA teams are looking for.”

C’ta DeLaurier used to spend hours shooting buckets at an old tire rim that was wrapped around a tree. Living in a remote town, socializing was limited so sport became a vice. Her dad, Brad, later encouraged her to get involved in the AAU circuit and from there she carved out a career at Rutgers and earned Atlantic 10 Tournament MVP honours in 1993. DeLaurier says her basketball journey inspired and influenced his love for the game and also his NBA path.

“One of the things we often say to each other is ‘humble-hungry,’” she said. “There is a degree of humility in everything that we do. Within that humility we can ration our appetite and that appetite lends itself to rigour, and that rigour leads itself to production.”

When DeLaurier wasn’t working in the Virginia summer heat, watching for snakes, labouring on long days, he was competing against his siblings at almost anything. Even skimming rocks and kickball in the front yard. When they weren’t playing basketball or wrestling, they were fishing and swimming in creeks and rivers at a nearby community called Schuyler, right in the foothills of Virginia’s Blue Ridge mountain range. C’ta referred to her brood as “country boys” and loves to compete against her sons. It’s a bond they share. Back then she schooled them at hoops; now the battle takes place with board games and cards.

When DeLaurier first learned he’d be signing a 10-day contract with the Milwaukee Bucks, C’ta said his first emotion was relief. Having watched her son grow through high school, be a captain at Duke University, play professionally in Canada, and then have an NBA experience she understands it wasn’t easy. She’s the kind of basketball mother who balances her advice between believing in her kids and being their harshest critic when she needs to be.

“As a parent of adult children, I’m finding that the most important thing is just to be available and present when they are ready to come to you,” she said. “I’m feeling humbled by the experience of Javin making the NBA. Javin has always believed in himself. I think this is just the beginning for him. This would not have happened if he wasn’t focused or had not honed his craft. He worked hard for this.”

The first thing Corey Frazier noticed about DeLaurier was that he had a knack for rebounding. His athleticism was as good as he’s seen. When DeLaurier came to him there were a lot of good parts he had in his toolbox already. But there were of course things he needed to work on. He needed to polish his shot and work on reinventing himself as a professional basketball player after four years in the college system.

“For the NBA you have got to at least be able to put yourself in position to score effectively and somewhat be a threat offensively,” said Frazier. “We had to change his mindset a little bit and get him to look at the basket a bit more.”

This year, between March and October, DeLaurier spent time with Frazier, a 17-year NBA trainer who’s worked with Bradley Beal, Jayson Tatum, and Moses Moody, in St.Louis in gyms like Mathews-Dickey Boys and Girls. The facility was a 15-minute drive north of downtown just off the I-70 sitting among an industrial hub, a Wendy’s, a police division, and Penrose Park Velodrome.

During their weekly sessions they tweaked the fluency and flow of DeLaurier’s jumper. They repeated drills that focused on back to the basket moves, catch-and-shoot shots from the top of the key, and got more comfortable with straight line drives. They returned to old film from his high school days, pulled it up, and studied the raw moves that made DeLaurier stand out as a teenager. It was to remind him what he was capable of. Frazier believes DeLaurier’s ceiling might be limitless and that he’s only just starting to scratch the surface of what he’s really capable of on the court.

“I think once guys get a taste of what that level is like they see they’re not far away. All they need is an opportunity. And right now he has that opportunity,” he said. “There’s no turning back. He’s really breaking out of his shell right now.”

Two years ago, DeLaurier was trying to figure out his next steps after coming out of Duke and going undrafted in the NBA. He wanted to keep his NBA dream alive. He ended up realizing one thing: keep believing in himself. His family, former coaches and his agent all believe that if he keeps putting in the work, and if he stays true to himself, the rest will figure itself out.

Durrant is working on another 10-day contract deal for DeLaurier. He says it’ll happen, it’s just a matter of when. With the pandemic heading into year three and with the rise of Omicron the path may appear just as murky as it did two years ago, but even with the uncertainty DeLaurier has still been able to chart a course to the NBA his own way.

“I try to leave the pondering and reminiscing outside of the arena. But it’s hard when you walk into the NBA for the first time and you’re wearing the jersey not to think about all of the steps that came before,” he said. “I’m just trying to live in the moment. Stay ready. And when my number is called, be ready to step out there and do my thing.”