Do yourself and Jermaine O’Neal a favor if you ever run into him. Don’t ask him about the Malice at the Palace.

“The one thing I get asked about weekly when people see me who have never met me before is about the damn brawl and I’m tired of talking about it,” says O’Neal.

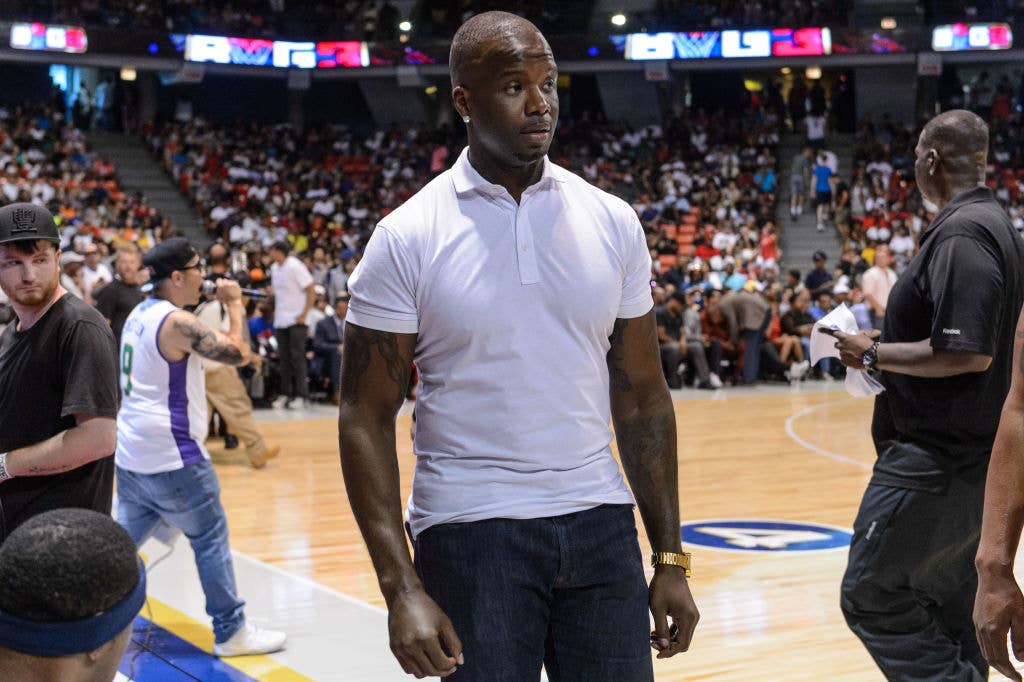

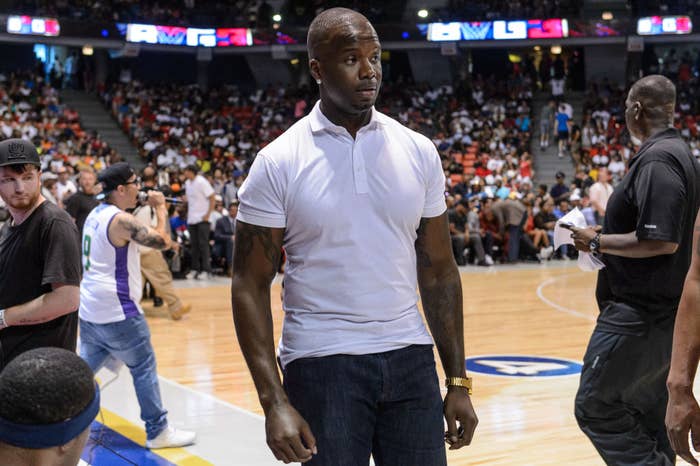

Seventeen years removed from the ugliest incident in NBA history, the retired big man who was at the center of the madness has always been loath to reminisce about the melee that broke out in Auburn Hills on a Friday night in November on national TV between Pacers players and Pistons fans. It’s almost always the first thing people bring up when they recognize him rather than the six straight All-Star Games he made with the Pacers, or the 18 years he spent in the league after entering as a teenager, or the other awesome things he did away from the basketball court.

After years of keeping quiet and waiting for the right platform to do so, you’ll soon to get to hear an unencumbered and emotional O’Neal talk about the toll the infamous incident took on him—and teammates Ron Artest (now Metta Sandifor-Artest) and Stephen Jackson—in “UNTOLD: Malice at the Palace,” a Netflix doc debuting Tuesday that offers up never before scene raw footage of the craziness and choice commentary from the three players who bore the brunt of the punishment in its aftermath.

Even if you’ve seen ESPN’s footage of the brawl a million times, read all kinds of articles about it, or consumed an oral history or two on the incident, chances are you’ll learn a few things in this doc. Like just how vulnerable the Pacers players really were on the court for 10 terrifying minutes, how the police almost pepper sprayed Artest and Reggie Mlller, and the damage the demonization of the players by the American media inflicted. We caught up with O’Neal, who serves as an executive producer of the doc, a week before its debut to ask him some of the questions he’s preferred not to answer.

“It’s a very sensitive subject for me,” O’Neal says via Zoom. “I have so much love and respect for the Indiana Pacers, for the NBA, for fans, because they do support us in many ways. But it was tough night, bro. It was a really tough night.”

[This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.]

There’s been plenty of content on the Malice at the Palace since it happened. Why did it feel right to participate in this?

It was more of a situation that I wanted to do it, to be honest. I’m not on record talking about it. And that’s really the reason I wanted to do it because people’s perception and the information out there isn’t necessarily the truth. I know Jack’s spoke about it, Metta’s spoke about it in a certain way. But I’m never sure if I’ve heard Metta—Imma call him Ron—speak about in the way he spoke about it.

“That’s the thing that’s sacrificed a little bit was how people viewed me as a person. I don’t care as much as a player because I was aggressive as a player. But when you walk away from this thing with people looking at you sideways, like you’re some hoodlum that doesn’t care about life, that’s a real problem for me.”

People have to realize when we put this doc together we didn’t do the interviews together. So when I saw the rough cut that was the first time I heard Ron speak about it, Stack speak about it in depth. I’m sure you’ve seen Reggie speak about it in others. There hasn’t been a doc that’s had as many people involved that’s telling the true story. Perception is these guys are just fighting and throwing punches and that was far from what happened. It was important for me from a perspective of my life where I’m tried about hearing about the brawl, the anniversary every single year and we’re 17 years removed. It was important for me to talk about it to tell that story.

Was it cathartic for you to talk about it finally? From my perspective, it didn’t look like it was the most comfortable thing to talk about.

So I’ve looked to do this for 10 years. I sat with producers and directors on this. A lot of people tried to put together the band. I’ve got to say a big thank you to Netflix and the Way brothers and the director Floyd Russ on understanding and seeing the vision and being part of an unbelievable series of docs. I wasn’t uncomfortable talking about it. There’s a lot of emotion behind it, obviously, for me personally. It’s important for me to put out there what the actual truth of it was and then people can come away with whatever perception they have. The one thing I get asked about weekly when people see me who have never met me before is about the damn brawl and I’m tired of talking about it.

How much does that bother you that people link you to that and ignore your long and successful NBA career?

Well, it is attached to me. Here’s the one thing people have to realize. There’s a lot of information out there that could’ve been used but it was chosen not to be used because at the time people were afraid of it. As much as I am an alumni of the NBA, love them, they gave me an opportunity to take care of my family for generations, but I understood it’s a bottom line number they have to address with 30 owners. That part bothered me. It bothered me, to a little bit, that the Pacers didn’t step up and say what they [should’ve] said. People think that when I got suspended that I was suspended for the entire time [Ed.’s note: O’Neal was initially suspended 25 games by the NBA following the incident before a federal arbitrator reduced it to 15 games.] I actually took the NBA to court, went through arbitration, got to a federal judge, and won and got reinstated because the judge said I had the right—and that’s important—the right to do what I did. A lot of people don’t know. The thing that killed me was the thug conversation, right. Some of the most respected analyst, and people I respect in the media, just went off and started talking about things they didn’t even really know about.

Let me ask you about the demonization of you guys in the media in the immediate aftermath. When that happened was that surprising or did you guys low-key expect that to come from all different avenues?

You have to expect something’s coming, that’s for sure. The quick-to-judge without even having real information, like any professional in any professional space, you have a job to do and that’s to get all the information you can get and then make your decisions. But everything was like boom, boom, boom. You start talking about culture, you start talking about braids, you start talking about tattoos, you’re basically talking about Black people. That was an issue to me. Look at hockey and baseball. They’ve notoriously been fighting leagues. They get to rush the mound in baseball. They get to take off the gloves [in hockey] and just go to work and there’s people chanting for that. We’re in a situation—and I’m speaking for myself here—that you have to react to the environment. And I ask you: What would you do in an arena and it’s 18,000 people and people are jumping across seats, throwing chairs, and everything else they can get to that’s not involved in a basketball game? What would you do? I will say this, too, people look at the sliding punch and that’s something they always talk about. They don’t realize I had just got a guy off my neck who had come from behind me and grabbed me by my neck and ended up throwing him on the scorer’s table. I look to my left and see Anthony Johnson, who had a broken hand and was in a brown suit so if you look at the actual punch you’ll see Anthony Johnson on the floor. I run over there and hit [the Pistons fan] because at that point it’s about protecting myself and others.

I understand that mentality and Stack had a great comment in the doc where he says it was “15 against 30,000.” There wasn’t really 30,000 fans in the arena when it happened, but you guys absolutely had the right to defend yourselves. But I’m curious how often you have those “what if” moments thinking about if that sliding punch actually landed flush on that fan?

I still stand on it. Let’s be honest, the perfect scenario would’ve been for the players just getting into it. I don’t think anybody involved in it wished it would’ve happened, right. I think everybody can say it was regretful. One part of being a leader on a basketball team is you have to be there for yourself and others. We’re stuck out there for 10-plus minutes and there’s not anyone coming in to help us and when they actually do they come to pepper spray us in uniform.

To be completely honest, I wanted to do this doc not to alienate anybody. The Pacers were phenomenal for me and my family, getting to grow as young man coming in there at 20, 21 years old. The NBA’s been phenomenal. The Pistons have been a foe, loved playing against them. It’s just more about education of people about this. I was just in Las Vegas coaching my son’s team. I must’ve been approached 10 times about the Malice. So for me, it’s more about moving on with my life, telling the story, and getting as many people there telling the story.

How vulnerable did you feel in those crazy few minutes on the court?

When I tell you the arena bared down on us quickly, with no security to save us, it puts you in a perspective of like...I’m surprised it didn’t make it on the doc, but [a camera] catches me starring, like I stop to look, it caught me off guard because I go from playing a basketball game to there are people out here trying to hurt us. They had no love for us that particular night. You get to thinking about what you need to do. And the problem people don’t realize is they were blocking our exits. So we were stuck out there. When the police actually get in there it’s not like an army of police officers, it’s like a handful of police officers that run in and they’re bypassing all the fans taking water bottles and lining us up or spitting on us or throwing things, chairs coming from everywhere. It was one of those things that you ask yourself, “How did I end up in this position over a basketball game?” When you look back at the situation, I don’t like talking about it. It’s one of those situations where I bared the worst of it. It’s a very sensitive subject for me. I have so much love and respect for the Indiana Pacers, for the NBA, for fans, because they do support us in many ways. But it was tough night, bro. It was a really tough night.

Reggie Miller said the Malice at the Palace cost people a lot things, like time and money. What did it ultimately cost you?

The first thing you look at is a championship. That is a very sour note for me. For one, Reggie meant so much to me. He could’ve easily told the Pacers not to trade for me because they came off the Finals that summer. Maybe he wanted to have another run at it, but as the superstar of the team he allowed basically an unproven guy [to have an opportunity] and my thing was to get him one because I was so young. So that stuck out to me the most. When people question your integrity, when people question who you are from afar, when they’ve never had a conversation with you, and don’t know the time and effort you’ve put into your communities, but then you’re kind of this thug, this out of control player, that makes no sense to me. That’s the thing that’s sacrificed a little bit was how people viewed me as a person. I don’t care as much as a player because I was aggressive as a player. But when you walk away from this thing with people looking at you sideways, like you’re some hoodlum that doesn’t care about life, that’s a real problem for me.

Have the conclusions you’ve drawn from the aftermath of the incident changed over the years?

It’s definitely not the same feelings toward it. I think maturity is something we all go through as we get older and we look at things, view things a little different. Even my relationship with Ron is a heck of a lot different than when we actually played together. I think the thing that’s learned is—and you just recently heard it with fans spitting on players and throwing popcorn on ‘em—it’s a balance that needs to happen and a level of education that needs to happen with fans. When you come out to the arena, we love the atmosphere of you booing and saying all kinds of stuff because that’s the competitive nature of coming into an opposing arena. But you have to understand that you do not own players because you bought a ticket. I will say this in closing: Never do anything in the arena that you would never do in the streets face-to-face.