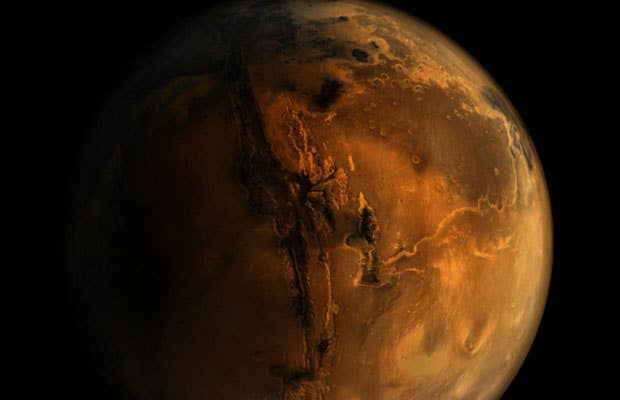

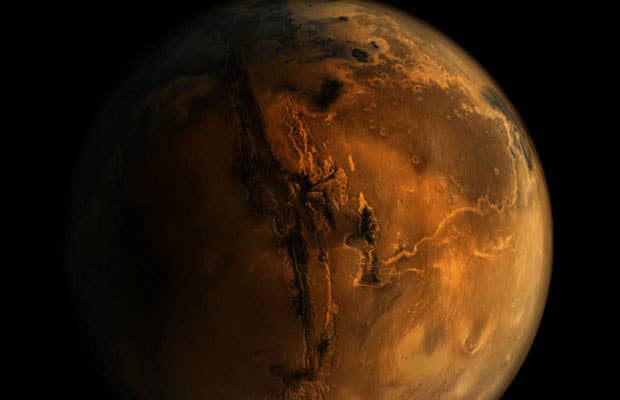

Life on Mars, reality television style. Spoiler: It doesn't end well.

Our romance with space travel has always been underscored by sorrow.

Beneath the grand optimism of rocket launches and big questions about why we're here is a backbeat of loss and isolation. One flies into space with the possibility of no return—and yet taking those leaps into oblivion without self-regard is the most essentially human act we can accomplish.

It's not surprising, then, that in just two weeks more than 78,000 people volunteered to take part in the Mars One Project, a new business initiative that will send a group of up to 40 people on a one-way trip to Mars.

With Mars One, it's almost impossible to imagine an outcome that isn't tragic. Yet, the inevitability of a horrific outcome is, in its own way, inseparable from the romance of space.

Those selected will undergo seven years of training on space travel and how to build a habitable colony on a wasteland planet whose gravitational pull is 38 percent as strong as Earth's. The $6 billion undertaking will partly be paid for by profits from a reality television show documenting the preparation for the 520-day trip and the challenges the group will face when they land on Mars. This will be supplemented by various licensing deals and merchandise sales, with the project's website already selling T-shirts, mugs, and posters.

While the project is heaping with promise, there are many reasons for skepticism. Lee Hutchinson of ArsTechnica points out the budget for NASA's Project Apollo between 1960 and 1969 totaled more than $16 billion for a simple trip to the moon.

Even more alarming: Of the managerial team so far assembled, most are tech entrepreneurs, marketers, and communications specialists. There is only one person on staff so far to address medical needs, and only co-founder and Chief Technical Officer Arno Wielders has any specific experience with Mars, having previously worked for the European Space Agency on a number of Mars missions.

At the recent Humans 2 Mars summit held in Washington, D.C., Richard Williams, NASA’s chief health and medical officer, spoke about a number of serious health threats on Mars, pointing to the planet’s apparently high concentration of perchlorates, which are known to damage the thyroid gland.

There are a number of other elements on the planet's surface that could do real damage to humans after extended exposure, which, even with space suits and breathing filtrations, would be impossible to eliminate. Like moon dust, the fine, static-riddled dirt on the surface of Mars would cling to space suits and machinery and inevitably be taken into sealed environments where humans could become exposed, leading to serious and potentially fatal health problems.

The technical details of the project also gloss over a number of important factors, like how the spacecraft would actually be able to land on the planet—a minor but puzzling detail that if taken for granted could instantly destroy all of the mission's equipment and kill the crew.

Likewise, it seems openly suicidal to plan to live on a planet that no human has ever yet reached when there are other options. Why not plan for a permanent residence on a space station, or a lunar colony instead?

The fixation on Mars can be seen as a byproduct of the grinding paralysis sweeping over the U.S. government, which once pursued projects like Apollo with gusto.

As anthropologist David Graeber argued in a recent interview with The Spectator, "It used to be actually possible to think big. To think about things like: the U.N., space programmes, the welfare state, and so on. Nowadays, no governments are thinking on anything like that scale, and they seem to be completely incapable of doing so."

Indeed, budget cuts to NASA have been significant in recent years, with Bill Nye of the Planetary Society calling the 2014 budget "shortsighted and disastrous."

As has been the case in recent decades in everything from education to healthcare, when the government's pursuit of massive structural projects declines, entrepreneurs step in with replacement projects.

And with Mars One, it's almost impossible to imagine an outcome that isn't tragic. Yet, the inevitability of a horrific outcome is, in its own way, inseparable from the romance of space. In the brief few decades we have had the capacity to reach outer space, one of the constants in every new mission is the further out we get, the more Earth begins to seem like a perfect home.

The best thing to see on the moon was the opalescent atmosphere of the third rock. And surely, after a year or 10 living in a metal research lab on the windblown face of Mars, the desire to sit in the shade of a tree beside some small body of water would become overwhelming.

Charting the journey to that inevitable conclusion will, at the very least, make for amazing television, and there are at least 78,000 potential actors willing to sacrifice their present lives to give us that gift of entertainment. Hopefully, it will end in a wedding and not a funeral—but, as they say in space, don't bother holding your breath.

Michael Thomsen is Complex.com's tech columnist. He has written for Slate, The Atlantic, The New Inquiry, Billboard, and is author of Levitate the Primate: Handjobs, Internet Dating, and Other Issues for Men. He tweets often at @mike_thomsen.