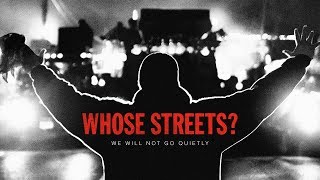

Three years ago, in Ferguson, Missouri, unarmed teenager Michael Brown Jr. died after being shot 12 times by police officer Darren Wilson. Peaceful protests were met with tear gas, lawful civil disobedience resulted in enforced curfews, and soon Ferguson became the epicenter of a movement fighting against institutionalized racism. Whose Streets?, a new documentary out today, showcases the residents of Ferguson who continue to lead the way and have devoted their lives to speaking truth to power. By comparison, Kathryn Bigelow’s Detroit, also released this month, is a hollow spectacle that tries desperately to tell an important story about police brutality but fails to engage with the systems of power that enforce it or to allow the audience to connect with its characters. Now that HBO recently announcedConfederate, in which the two white guys responsible for Game of Thrones will create an alternate history in which the South won the civil war, many fear that this new show will follow in Detroit’s footsteps, imagining a world that is not constructive and does not help the advancement of black Americans. These stories have all come at a time when other diverse black stories such as Atlanta, Insecure, Moonlight, and Get Out have been wildly successful, so why do some fail and others succeed?

Detroit is a fictionalized imagining of the real riots that spread throughout Detroit in the summer of 1967 after a raid on an illegal nightclub, but the majority of the film’s action takes place in a hallway in the Algiers Motel, where three innocent black men died and a few others were severely beaten after three cops break protocol during an interrogation. It’s horrific, but screenwriter Mark Boal fails to bring the victims to life so that all we really know about these black men who are savagely beaten and killed that night is their race. Bigelow fails to explore the source of its brutality; we feel a basic sense of urgency and empathy, but only the violence is condemned and not the system that emboldens officers and disempowers people of color in the first place. The police chief, an ultimate source of authority, positions himself in stark opposition to his three offending officers, effectively taking viewers off the hook for any uncomfortable conversations: at least the police chief tried his best, right?

It’s a shame, because three years after Michael Brown Jr. died, Detroit feels eerily familiar. Whose Streets? is an incendiary look into what happens after the police abuse their power, showcasing Ferguson both as city and symbol. Filmmakers Saabah Folayan and Damon Davis have a razor sharp focus that Bigelow doesn’t: institutionalized racism results in the loss of innocent lives, and in America, it is often easier to get away with killing an innocent black man than to fight for your rights.

Whose Streets? is completely dependent on its extensive interviews with Ferguson residents and activists whose lives were changed on August 9, 2014 and have dedicated their lives to showing truth to power. And that’s by design. Folayan and Davis worked hard to contextualize the unrest by respecting the community they portray. “We decided very early on that we were not going to use black bodies as a prop. We would only show Mike Brown Jr. alive, and blur out his body,” Folayan explains. “Too often we get minimized to our deaths.”

It’s not easy to re-visit scenes of tanks and tear gas on the streets of Ferguson, especially because they don’t look much different from Bigelow’s fictionalized scenes of Detroit. Folayan and Davis make a point to follow powerful characters who help explain why that response was disproportionate. The news footage that is sprinkled throughout shows how Ferguson looked to the world: chaotic, dangerous. But when Folayan and Davis take the time to ask the residents of Ferguson why they protest, it’s a different story. Take, for example, Brittany Ferrell, one of the main activists profiled in the doc, who speaks candidly about the effects of her activism on her young daughter Kenna. When a child has to grow up scared that her mother might not return from a peaceful protest, that child’s society has failed her; Kenna’s fear also demonstrates the generational effects of police brutality. Nevertheless, in one of the final scenes, Kenna is the one who shouts out Brittany’s signature phrase: “we have nothing left to lose but our chains.” In that moment, any smidge of fear you felt for Kenna is washed away and you can’t help but smile. You’re smiling because you realize through activism, there is hope.

“We wanted to humanize these black people who rarely get to be complex people on camera,” Davis explains. “It’s definitely targeted towards black people, we’re not shying away from that, but anybody with a heart can put themselves in these people’s shoes.” And therein lies the power of Whose Streets? Its distinctly personal approach inspires compassion. We scoff at the CNN reporter who looks into the camera and has the gall to turn to his camera and say “What was supposed to be a peaceful vigil turned into this.” We understand that “this” is but a community’s palpable anger at a system that fails to respect them and whose protests are routinely met with disproportionate violence. Folayan and Davis’s camera weaves through the nights of peaceful vigil and civil disobedience and the people on the streets tell the camera themselves why they are there. Detroit fails to give any character even one significant line of dialogue that might help explain why a single nightclub raid was the catalyst for a summer of lootings and riots, so that the subsequent violence becomes a disturbing vacant performance.

In an interview withVariety about Detroit, Bigelow admits she does not believe she is the “perfect person to tell this story.” But, she continues, “I’m able to tell this story, and it’s been 50 years since it’s been told.” But now that stories about marginalized people are inching closer to the mainstream, who is the “perfect” person to tell a story?

Take, for example, last month’s announcement that acclaimed Game of Thrones showrunners D. B. Weiss and David Benioff will shift their focus from dragons to a science-fiction show called Confederate, which “takes place in an alternate timeline, where the southern states have successfully seceded from the Union, giving rise to a nation in which slavery remains legal and has evolved into a modern institution.” The backlash was immediate and it was fierce, but it should be stated emphatically that there is nothing inherently wrong with the concept. That these two (white) men want to spend the influence and cultural cache they gained from Game of Thrones on a story about race in America is, at least in theory, commendable.

With that said, for the families of Michael Brown, Philando Castille, Trayvon Martin, Freddie Gray, Eric Garner, and countless others, that fundamental assertion of the confederacy, that black people are not worthy of respect because of the color of their skin, was not eradicated when the civil war ended. The Confederate flag is a prominent part of the Mississippi state flag. Our Attorney General, Jeff Sessions, once “joked” that he only considered the KKK an issue once he realized they smoked marijuana. For many Americans, Confederate is not science-fiction. As Ta Nehisi Coates puts it, “Confederate is the kind of provocative thought experiment that can be engaged in when someone else’s lived reality really is fantasy to you.”

Weiss and Benioff’s desire to tackle the thorniest parts of American society probably come from a similar place as Bigelow’s: they understand the importance of stories about race and want to use their platforms to tackle them, and they have the right to do so. Bigelow, Weiss and Benioff are not racist, but their experience of history as white people is, by definition, different than that of the black people whose stories they wish to explore. They must come to terms with that gap before their scripts are funded by major studios, not afterwards. Detroit fails because it is fascinated by violence against black bodies and not by the individuals in those bodies. That violence is important, but it rings hollow if not accompanied by meaningful commentary about the systems that have allowed it in the first place. Similarly, many are concerned that the guys behind one of the most violent shows on television will receive millions of dollars to shock rather than explore delicate, nuanced storylines.

Whose Streets? succeeds in that regard not because it was made by black people, but because the filmmakers’ prime goal was to give a community who has felt the effects of police brutality first-hand the stage. “People are used to consuming stories about what it’s like to be back and what the black experience is through the lens of somebody sitting them down and teaching them what it is,” Folayan concludes. “We wanted to really try to guide and teach people how to understand our experiences through a normal lens, to not cater to the idea that we’re some other community. We’re Americans. I want audiences to learn how to see us in that light.”