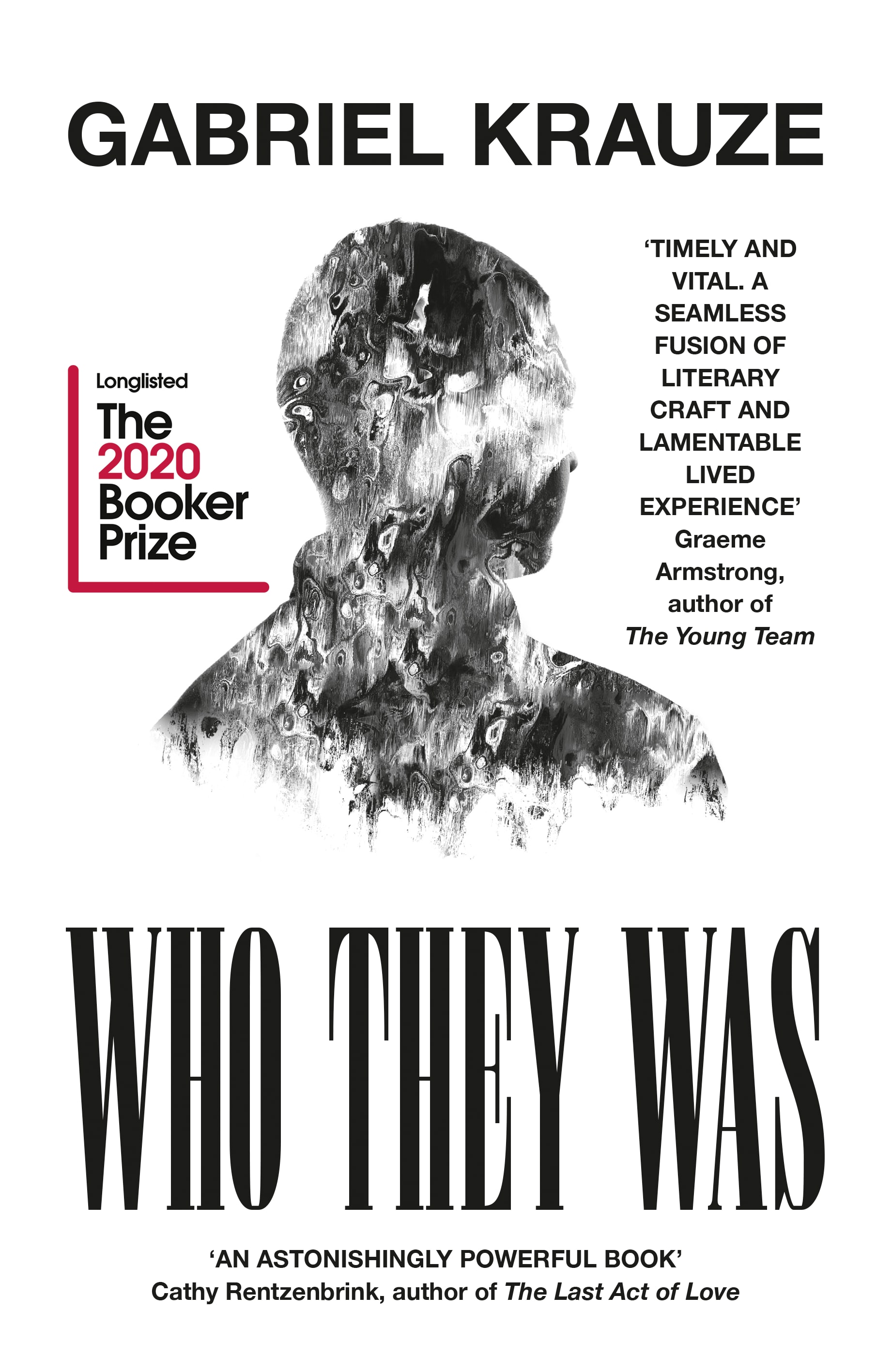

If you’re looking for a potentially uncomfortable read, the kind that depicts treading the London underworld paths they don’t mention in the guidebooks, then pick up Gabriel Krauze’s Booker-longlisted debut novel, Who They Was.

While UK street culture has become a source of inspiration around the world, with homegrown music, films and TV shows regularly regarded as part of the mainstream zeitgeist, the same can’t be said for literature. As books go, this is something of a first. South Kilburn-raised Krauze—the son of Polish immigrants—has delivered an autobiographical work of fiction that centres around a younger self who gets caught up in the darker side of life—getting deeper into the roads—all while studying for an English degree. Written in just five months (initially by pen), Krauze’s writing is perhaps even more arresting than some of the crimes he notes in this 336-pager.

Already lauded by critics, Who They Was could—and should—prove a historical turning point for British literature and future, as yet unheard, voices. Chantelle Fiddy speaks with Gabriel Krauze about stereotypes, privilege, existentialism and those cold, cold roads.

“If I’d been Black, I’d have been locked up quicker and for longer.”

COMPLEX: I’m assuming you’re a big reader?

Gabriel Krauze: I remember as a child reading books and being given books as presents by my parents, but I didn’t ever think it was abnormal: the idea of being entertained with books. It’s a very normal thing to me. My family didn’t have a lot of money. We didn’t have a big TV or games consoles and shit like that. Having artistic parents, they’d give us sheets of paper, pens and pencils to amuse us with. It was just a culture I grew up in.

Your debut novel, Who They Was, focuses on street life and criminal dealings. Did being a big reader help you in any way out of the life that you were living?

There’s a lot of people who believe that a life of crime or violence isn’t synonymous with an appreciation of the arts, literature, film... I’ve had some of the most interesting and enlightening conversations about philosophy and literature with people who are doing road as well, but they just happen to be unique people, with their own pursuits and interests. And I need to emphasise this: I am NOT comparing myself to Caravaggio, but he created some of the most amazing, powerful art in the history of painting and he was also on the run for a large part of his life for killing someone in a knife fight. There’s this idea in modern times, because of moral fears, that you can’t be both cultured and a criminal.

Are you aiming to break down the stereotype of the ‘roadman’?

I always find it mad when the media convey this image of the ‘roadman’ as all we do is go around shottin’ food, shanking people, no extensive interests—and that doesn’t mean we’re watching Scarface on repeat. The amount of people I know who are into Japanese cinema and Anime but are on road, it’s mad.

Road life gets fetishised, too. Have stereotypes been broken via film and TV yet?

There’s been some good stuff, but some miss the mark. The other thing about breaking stereotypes is there’s a really unhealthy aspect of the media’s reporting of crime—especially crime in London—linking it to “Black on Black crime.” One of the important things I feel my book is doing is challenging perceptions in that I am white and I was deeply involved in this criminal life. But, like in the chapter where I get arrested, there’s people saying, “he’s mixed-race”, making assumptions based on racial prejudice. I’m not setting out to do that, or trying to make it topical, but in telling the truth—because that’s the biggest thing I’m concerned with— I’m revealing this reality.

Do you think you being white prevented you from doing more time, and did you ever feel that privilege on-road or when you got arrested?

100% with the legal system. That’s not difficult to answer at all. If I’d been Black, I’d have been locked up quicker and for longer. I only did two weeks on remand in Feltham, and six weeks in Bullingdon.

How do you write a book like Who They Was without feeling like a snitch?

The way I fictionalised the book is what I did to protect others and myself legally. I sent bits that involved my friends to them first and the overwhelming response I got was, “Rah! how do you remember that so well?” Whenever I got that response, it felt really good as I’ve realised I’m trying to immortalise the reality of a world which, as we grow up and get older, becomes forgotten. And there’s bare legends, bare stories, bare experiences of people who have done crazy stuff. The book doesn’t have some easy-to-accept or redemptive moment that’ll reassure the reader and make them feel okay. We’re not riding into the sunset or being saved by Jesus cause that’s not real life. Life doesn’t have finality. Real life always carries on. To portray the reality of that world and the complexities of the characters, you can’t have these archetypal ideas of a person who has a redemptive moment just because it will satisfy readership. Don’t get me wrong: I know man who know bare man who’ve found religion, usually Christianity or Islam, but that didn’t happen for me. You go through this world, this life thinking it’s always going to keep going but there’s always someone else missing. Even if I look at how I got out, it’s much more complex than that.

So how did you get to this point with the book?

The book took me five months. I didn’t have to spend time imagining or thinking things up, and one thing I used to do was obsessively write anecdotes about things that had happened. When I sat down to write the book, I had all this material written on the back of probation reports, uni assignments, scraps of paper, two or three old phones worth of notes and recorded conversations. I used all this material to stitch it together into this story of my life. There are contractions of time in the fictionalisation, but I didn’t have to think about characters. I could write vividly because these are people I’ve lived with and know in a very personal way. I wrote the book by hand; pen on paper. It’s how I write—like writing lyrics—then I spent five months typing it up. I think it took me longer to type it up than to write it because that was an unpleasant experience for me. But by typing it, I got to edit it so that was good. Then I sent it out to agents and got good interest. There was one agent who asked me how much was true and when I told her all of it, she backed out. She was worried I’d go to prison but I joked that if that were to happen, I’d use the time to write another book... Whatever happens to me in this life, I’ll take it and deal with it. But on a serious note, the book is ultimately a novel—a work of fiction—and should be read as such. A lot of people are risk averse, but not me.

How did your parents react to it? It must be a hard read for them.

I gave them the first two printed copies. They haven’t gone in-depth about how they feel but they remember how many times the police were at the doors. The other day, my dad mentioned the Gestapo hours which is what he thinks of as 3, 4 in the morning, hoping to catch you in your bed. They’ve seen actively how I’ve turned my life around and are very proud of me.

The thought of my parents reading about my sexual exploits is too much.

It’s a bit mad! My mum sent me a list of words she wanted me to explain and one of them was “neck-back” and I was like, “Oh nooo!”

At the start, when the slang kicked in, I wondered if it was going to be tokenistic. But it’s not.

It’s supposed to feel like I’m sat in a room with you and I’m telling you the story. It’s almost like I don’t want the reader to breathe…

—and that’s how it felt and why I read it so quickly.

And for people who know the slang, they’ll fly through it because they won’t question the language. But I think a more traditional reader will be able to work it out and there’s an aspect that’s not necessarily meant to be understandable. It heightens the sense that we exist in these different worlds, same city, but where you’re from and I’m from are two separate worlds. That’s part of it; the wider expression is the language in which the book is written. You’re now basically inside one of these other worlds and if you don’t speak the slang—welcome, the door is open: step into this world. Equally, you might not understand everything linguistically, then it transposes itself into the moral questions; you might not understand the amorality or the existential or nihilistic life or our attitudes to other people and victims, but that’s because you’ve entered a different reality.

“The only thing I care about is aiming for the pinnacle as a writer: being compared to Dostoevsky, James Baldwin or Toni Morrison.”

Are the girls you’ve written about cool with it?

Some of the girls I know can’t wait to read it and show their mums. I’m sure there will be some women who will read the book and say it’s very misogynistic, but this is important and crucial to telling the truth. The book is written in my voice between the ages of 18 and 23, when I was deeply in this life, and I wanted to preserve the accuracy, voice, feelings and perspective attached to the time. I remember when I read the notes I’d written in Feltham, about people, society… I was like, “Fuckin’ hell! I can’t believe I used to think like this.” And one thing I had to keep doing with the book was restrain myself from applying the perspectives I have now, and the change in me that’s happened since then. I can’t suddenly be mad objective or worldly and have empathy when, for a start, you’re committing crimes like that—you can’t have mad empathy or a wide moral spectrum or you won’t be capable of doing that shit.

In the book, it feels like you held yourself back in relationships.

Exactly, and it might be misogynistic but that’s what it’s like. Actually, it’s a lot worse. There’s a lot of stuff I didn’t put in the book and there’s a lot of stuff I cut out because it got to the point where I thought it was too much. People need to know how fucked up the perspectives a lot of young men hold are. And also, that a lot of young women are obsessed with the materialism or the idea of a badman.

What’s your ambition?

I want to keep writing books. I’d like to write films as well, TV series… I have an idea at some point to drop an EP, as I used to rap. I’ve got a lot of bars, banging bars. I’m about to drop a video which I created for the book and when I went to record the voiceover, my boy’s Fredo’s engineer, so I laid down a freestyle there. I still write lyrics; I’m deeply linked to that. I’m very passionate about rap. I’m also passed it too. I’m not trying to define myself as a rapper, have a rap career. I’d love to collaborate with some rappers who might use the audio book clips as skits or something.

To someone who is aspiring to get into writing, what’s your advice?

There’s this great line by Hemingway in A Moveable Feast, which he wrote about being a young writer in Paris, and he talks about not knowing what to write and being stuck. He’s staring out across the rooftops of Paris and he sits down and realises all he has to do is write the truest thing. And as long as he can write the truest thing, he’ll be okay. Everyone can write the truest thing to themselves. Sometimes, you have to sit in front of a blank page for an hour before it comes to you and hits you, but it’s having the discipline to being committed to what you’re trying to do. Whatever wants to spill out, start from there. In terms of the end process, you might go back and get rid of the beginning but it’s about unlocking the writing process. It’s essential. The only thing I care about is aiming for the pinnacle as a writer: being compared to Dostoevsky, James Baldwin or Toni Morrison.

What’s your current soundtrack?

Griselda, a rap trio from Buffalo, New York. Shout out Griselda. Holla at me! They’re a big influence, musically. UK-wise, I love M1llionz—I’m a huge fan. He’s heavy! I was really into J Hus; definitely one of my favourites. Freddie Gibbs, too, and I still listen to a lot of old Nas. It Was Written is probably my No.1 album of all time in rap. Illmatic has to come second for me. What Nas achieved is literature. That’s what he wrote with those lyrics.

Who They Was by Gabriel Krauze is published by Fourth Estate. Buy your copy here.