1.

Image via Gasa Gasa

Cannibal Ox announced their reunion on November 13th, 2012.

For a devout fan of Definitive Jux, the label that played home to the group’s seminal album Cold Vein, a Can Ox reunion show was big news. The New York duo of Vast Aire and Vordul Mega released one of underground hip hop’s seminal albums in 2001. Cold Vein formed a cornerstone for a label solidifying itself as the leading purveyor of independent, cutting edge rap music at the dawn of the new millennium.

For a 14-year-old New Yorker newly discovering alternative hip hop through the good fortune of older friends and the primordial rap internet, Cold Vein served as a sort of holy scripture. Vast and Vordul combined street observation, science fiction, and personal narrative atop El-P’s ambitious, cinematic production to make something unlike anything that came before or since—Cold Vein played as Blade Runner set in present day Harlem, a perfect encapsulation of post-9/11 New York (in spite of being released four months before the towers fell): grim, claustrophobic, surreal, dystopian, and, still in all, a city of tremendous possibility, a place where, as Cannibal Ox put it, the pigeon could transform into a phoenix.

I can comfortably call it one of my five to ten favorite albums ever (perhaps even in the top three, depending on day) and an album I can readily argue as one of the most important in hip hop history.

A Cannibal Ox reunion show was a major fucking deal for me.

Though the duo had long teased a follow up to their groundbreaking debut, nothing came save for a stream of spotty solo releases that shined in moments but couldn’t match the scope or execution of Cold Vein. On hiatus for years, the group never officially disbanded, leaving room for the tantalizing possibility of new music.

On Feb 3rd 2010, El-P announced the shuttering of Definitive Jux, citing changing times and a desire to recommit himself to creative pursuits:

“As a traditional record label DEF JUX will effectively be put on hiatus. We are not closing, but we are changing…In 2000 starting a traditional record label made a lot of sense. But now, in 2010, less so and I find myself yearning for something else to put my energy into. I also see newer, smarter, more interesting things on the horizon for the way art and commerce intersect, and as an artist and an entrepreneur, I’m eager to see them unfold.”

(The Brooklyn rapper/producer’s choice has paid huge dividends, resulting first in his excellent 2012 solo album Cancer For Cure and, shortly thereafter, his late career renaissance alongside Atlanta stalwart Killer Mike as one half of Run the Jewels)

The end of Definitive Jux effectively signaled the end of an era—the dawn of streaming, the violent transformation of the major label system (and distribution in general), and the maturation of music discovery on the internet were about to morph what it meant to be a rapper and an independent artist—but it also seemed like the collapse of a personal dream: A follow up to Cold Vein would likely never come; if it did, it wouldn’t bear the Definitive Jux imprint.

As my Twitter bio says: ‘I owe everything to Def Jux.’

By 2012, I’d pretty much abandoned hope of any Cannibal Ox-related windfalls. I didn’t actively pine for a return to the glory days of Definitive Jux, but the label’s output and ethos always remains etched in my heart and philosophically present in the background radiation of my brain. As my Twitter bio says: “I owe everything to Def Jux.”

I first got in touch with Jacob (aka Confusion) in May of 2011 with a pitch—I wanted to write an oral history of my favorite label and arguably one of independent music’s most important. Jacob was more than game for the idea. After a year of back and forth and a number of reasons not worth enumerating, we realized we wouldn’t be able to pull the piece off. In the wake of its disintegration, I asked Jacob if he’d give me a shot as a daily contributor. Over the preceding twelve months, he’d figured out that I was a moderately sentient human being with a pulse and some awareness of music. He said yes, beginning a journey of nearly four very strange years and counting. Six months after I penned my first words for P&P, I received an email from Jacob: Cannibal Ox was reuniting.

“Jon, Khal, anyone else in NY who cares… we haaaaave to go to this”

It was a foregone conclusion.

“Yesssss should we cop tix now?”

“I bought 2 already, assuming that one of you will come with me. You should both come”

I couldn’t miss it. My usual laziness and lack of desire to leave the house on a Sunday night crumbled at the promise of seeing heros in the flesh.

“Yeah you can absolutely count me in.”

My loving, attentive girlfriend at the time saw just how excited this news made me and, in turn, made a grave error:

“I want to come too.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yeah, I want to understand something that you love so much.”

“Let me at least buy your ticket.”

I warned her.

About the esoteric nature of the music.

About how bad rap underground rap shows could be.

About the promise of disorganization, hoodies, and beer smell—trademarks of an underground rap show.

Never a huge fan of hip-hop and certainly not hip-hop as off the beaten path as Cold Vein, she persisted nonetheless, admirable in her sense of adventurism and desire to understand something her significant other loved so much (I’d thank her for soldiering through this night for years to follow). I could already see this small experiment turning south. My blind enthusiasm swept my girlfriend up in a wave soon to crash.

On Sunday, December 9, Jacob, my girlfriend, and I went to the single worst rap concert I have ever attended. So bad that the next morning it inspired a heated email thread with Jacob and Khal and, ultimately a mournful article about what we had just witnessed.

By the time we reached the Knitting Factory, my excitement had reached an impossible pitch, stoked by serendipity on the L train: A woman claiming to have purchased and eventually resold Death Row Records struck up a conversation with my girlfriend and me. She told us stories about Suge Knight, about million dollar deals. She told me to email her to set up an interview. I never did, but I was thrilled by such a fanciful conversation en route to Valhalla.

Doors opened at 8 p.m. for a supposed 9 p.m. start. We arrived around 9:05 p.m.. I snuck a peek at a set schedule by the door: “11:40 – Cannibal Ox.” Alright. I’ll deal.

One beer in, and my excitement hit the supercharge of an oncoming buzz.

“I wonder what they’ll play first,” I said to my girlfriend, fully expecting her to have no response. I was just thrilled she kept humoring my irrational passion. “I hope they play the album in order.”

Jacob joined us shortly thereafter. Beer number two soon followed. We talked about life, about Pigeons & Planes expanding in 2013 after a year of steady growth, about what we’d write about the show tomorrow.

From the moment a patently, persistently unfunny host took the stage, the night turned sickeningly surreal.

Wearing what I described to Khal the next day as “one of the ugliest Argyle sweaters I’ve seen in all my days,” the host spent a ton of time stalling for the three hours worth of opening acts who rarely came out on time. He got no one excited for them, let alone for the main and, as far as I was concerned, only event: Cannibal Ox.

Aided by the the sweetness of hard cider, my girlfriend braved a sea of struggle rappers as I glanced at her periodically, hoping for the best. Sheepish smiles in response.

Starting with the first act (whose name I’ve blissfully forgotten), the calls for “real hip-hop” and “bringin’ it back” from the various rappers on stage came like an endless siege on my desire to continue loving rap music. The whole night felt like a parody. When one rapper said, “Yeah, I like swag rap,” he sounded so out of touch with anything actually going on in hip-hop at the moment, that he might as well have been my father reading a Wikipedia article on A$AP Rocky from the stage and then imitating Ice Cube circa 1990 except without humor or talent or any redeeming qualities other than the fact that he eventually had the good sense to leave the stage.

“I’m really sorry about this,” I told my girlfriend. “They should be on soon.”

It was 10:30 p.m.

“It’s ok,” she told me. Yawns and drooping eyes said otherwise. My hope waned and, worse yet, she endured the sideshow on my behalf.

“If they’re not on by midnight, we’ll leave.”

“No no, it’s OK. I want you to see them!”

By this point, I wasn’t sure I even wanted to see Cannibal Ox anymore. A bittersweet brew of hope and fear bubbled in my stomach.

“You’re the best,” I told her, thinking about how badly I wanted to be back in my apartment and not sipping a stale beer as I waited for the inevitable, awful other shoe to drop.

11:40 p.m.

Still no Cannibal Ox.

C Rayz Walz, another Definitive Jux alum and fan favorite of New York’s underground scene, took the stage near midnight.

“This is C Rayz Walz,” I told my girlfriend. “He’s the last one before Cannibal Ox, so it can’t be that long now.”

Her “OK” came through the cloud of a yawn.

C Rayz played a few songs from his Definitive Jux releases before diving into new material and speaking of “fucking the audience with this hip-hop dick.” At one point, angered that no one was rapping along, he walked over to the DJ stand and took control of the fader. He dipped out the volume every few bars, demanding audience response. At one point during this painful exercise, he said, “Y’all ‘sposed to be Def Jux fans?” A few moments later, he paused and a woman called out “I don’t know this song!” And everyone laughed, because it was the truest, best moment of a night that couldn’t be put out of its misery.

C Rayz left the stage at 12:40 a.m.

“I’m really sorry,” I whispered to my girlfriend. I don’t think she said anything, exhaustion depriving her of negative or positive response. “This is unusually bad. I warned you, but I didn’t realize it would be this bad.”

Nothing. My mind drifted from the concert to the list of ways I could potentially make this night up to her.

Near 1:00 a.m., Cannibal Ox took the stage.

They performed four songs from Cold Vein before my girlfriend and I left. They were fine to start, totally serviceable, a little sloppy—the music carried them, still as fresh and incomparable as it had been when I first heard it as a 13-year-old.

“Let’s go,” I told her, barely 20 minutes into something I’d essentially waited to see for over a decade. By that point, she was practically falling asleep on her feet, we collectively had to get up at 6 a.m., and I imagined downhill as the only direction for the rest of the show. They’d played three of my favorite songs. I was ready.

Apparently, I made the right decision:

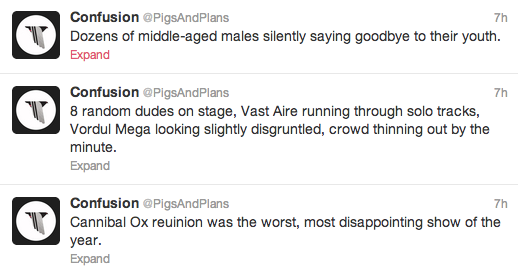

5.

Jacob’s tweets from shortly after my exit.

I learned two lessons that night.

First, and perhaps a truism: Everything is not for everyone. My girlfriend may have learned this lesson hardest of all. NY underground hip-hop represents a very specific moment in time, one that, transported to the Knitting Factory that night, still probably spoke to many of the people standing around us at the show. (I remember comments—lost to a comment system change up years back—on our original article corroborating Jacob and my observations, but also several calling us crazy haters). It’s a simple lesson, but one put in high relief by the experience. To paraphrase my email exchange with Jacob and Khal, by the time we left the venue, I’d already promised to cook dinner for my girlfriend and take dance lessons with her in return for her patience with the night’s sideshow.

The second lesson is no less familiar, but one harder learned and more readily forgotten: Sometimes the past should stay in the past. As Khal bluntly stated in our email post mortem, “nostalgia rocks. just don’t expect those people to continue to do great shit.” Cold Vein captured a specific moment—two inventive young rappers and an iconoclastic producer teaming up for an album comparable to little in hip-hop’s history. I wholeheartedly support the right of all three to keep making music and would never argue that someone should stop creating just because they made something great once. For artists, it’s important to understand what your fans connected to in the past and, in your way, to honor that bond. For fans, it’s important to either have lowered expectations when the nostalgia train swings around or to preserve the past in amber, a gem consigned to specific contexts. Time inevitably sinks its teeth into human endeavor and tears it apart. Art’s power often takes root so firmly in fragile emotions that it doesn’t make sense to expose cherished sentiments to the realities of aging. Sometimes you need to take a step back, hold on to beauty as you remember, and stop your imagination from returning to the graveyard of good memories.