1.

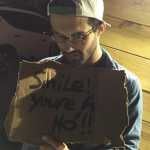

Image via Jon Tanners

I landed in Los Angeles around 10AM, finally on the other side of a one way ticket that had hung over my head for a month like impending prophecy.

Trek through airport, bloodshot eyes forcing themselves open.

Retrieve rental car.

Get out of Enterprise parking lot.

But first, a song.

An act of theater for an audience of one: I dug an auxiliary cord out of my bag, plugged in my iPod, and turned on Mobb Deep’s “Shook Ones.”

I tugged at New York. Stubborn. Still unwilling to admit to myself that I might have to consider getting a California driver’s license in the not-so-distant future.

“Shook Ones” had long been a personal favorite. It had seen me through break ups. It had propped me up during arguments about the greatest hardcore hip hop songs ever. I knew every word, every second of the beat. “Shook Ones” represented a kind of New York truth: claustrophobic, paranoid, cold, violent, and matured beyond its years by the blunt force of the big apple.

I drove up La Cienega with the windows down. 75 and sunny. The quintessential L.A. morning. I couldn’t have picked a less fitting soundtrack.

As a New Yorker, I celebrated the primacy of my city in the hip hop landscape—an ebbing relevance by the time the I’d graduated high school, relevance all but gone in the present popular landscape.

The summer before I started college, I picked up a copy of author Roni Sarig’s Third Coast: Outkast, Timbaland, and How Hip Hop Became A Southern Thing. I’d gotten tastes of the South in high school—Outkast had already been a favorite for years (who could deny “Still Tippin’” and “What You Know” when they ruled the world), and Lil Wayne’s mixtape run made him patently unavoidable—but I had little sense of southern hip-hop’s history. As a New Yorker, I celebrated the primacy of my city in the hip hop landscape—an ebbing relevance by the time the I’d graduated high school, relevance all but gone in the present popular landscape. I figured even if my snobbish New York sensibilities prevented me from loving some of it, I wanted to understand the Third Coast’s musical legacy in far greater depth.

No hip hop history can be perfect or fully inclusive, but Sarig’s look at the South paints an excellent introductory picture.

Through Sarig’s work, I learned of Houston, of the slow sprawl that made sense of “Still Tippin’s” ominous, trunk-rattling crawl and the hypnotic, syrupy slowness of DJ’s Screw’s signature style.

I read about Miami and the endless party that made an unofficial mayor of Uncle Luke, the leader of bass music—the fast, heavy party-starting subgenre that Luke’s Too Live Crew hoisted to national infamy on the heels of songs like “Me So Horny.” Years after reading Third Coast, I traveled to Miami as a wide-eyed 24-year-old Epic Records A&R. Eternal spring break swallowed me whole and Miami bass suddenly made perfect sense.

Most crucially, Sarig opened my eyes to New Orleans, and perhaps my favorite hip hop sub-genre, bounce. One of the first pieces I ever wrote for P&P was a small peek at bounce in light of Diplo’s “Express Yourself,” the 2012 single that brought an EDM-ified version of the style to a new audience. Bounce fascinated me with its sampling, general irreverence, and curiously neat encapsulation of hip hop history with an active, southern twist.

In brief: Bounce began with New Orleans producers and DJ’s sampling “Drag Rap,” a minor record from the 1980s by New York duo the Showboyz. These forefathers mistakenly believed the song’s name to be “Triggerman,” birthing the sample that formed the backbone of the sound.

DJ Jimi’s popular “Where Dey At” set the blueprint: fast-paced 808s, an almost proto-Girl Talk attention span for samples, highly sexual chanting meant for call and response, and, of course, “Triggerman.”

Bounce evolved over time, one of hip hop’s most resilient and malleable sub genres (it has existed in some form or fashion since the 1980s, so keep that in mind when you want to quickly dismiss trap). It played raucous party starter with Magnolia Shorty’s “Monkey On The D$ck” in 1996 and Li’l Goldie’s “Act A Donkey On A…,” local hits that play off the same construction and explicit concept. It pierced national consciousness through subtle incorporation by Mannie Fresh and Juvenile—two of bounce’s earliest creators—on 1999 megahit “Back That Azz Up.” Artists like Big Freedia continue to push boundaries and inspire ass-shaking with sissy bounce, a spin on the sub-genre featuring openly gay rappers.

Earlier this year, I went to New Orleans as an adult for the first time. I’d gone as an 18-year-old on a high school trip, but I hardly saw anything of a city still reeling from Hurricane Katrina. Arriving on a Saturday morning and leaving the next night, I took in a whirlwind of colors, tastes, sounds, and bodies, the classic American melting pot that feels distant from our fractured present. Bounce perfectly encapsulated the history of a resourceful, resilient, fun-loving city—one that aggressively defends its freedom to be New Orleans and resists the infiltration of other, lesser forces.

Situational specificity often defines sound and shapes a genre’s meaning, facts easily comprehended, but difficult to feel through tinny headphones.

We can forget in our homes and our headphones, in iPhone earbuds and Beats Pills, that music exists in larger context. In the age of infinite internet accessible, the importance of experiencing music in its proper place—whatever that may mean; it can mean at home, alone—has lost a bit of luster. Situational specificity often defines sound and shapes a genre’s meaning, facts easily comprehended, but difficult to feel through tinny headphones.

Mobb Deep made complete sense for my time in New York—for late night walks through strange neighborhoods, for claustrophobic streets, on subway trains, and in packed, dimly lit bars. “Shook Ones” embodies paranoia, pain, and anger, a perpetual New York winter transmuted into music.

“Shook Ones” stopped making sense as something other than a great song and a peg for nostalgia as I drove up La Cienega towards the floor that would be my bed for a month in Santa Monica—a place where having a floor for a bed can seem like thousand thread count heaven because it’s so damn sunny and pleasant all the time. I landed in Los Angeles and almost immediately understood why people liked Dom Kennedy, why “Nuthin But A G Thing” curled out of speakers like smoke, and Kendrick felt the need to share “The Recipe”: palm trees, open spaces, beautiful weather, and big dreams.

In 25 straight years of living in New York, I’d never had empathetic ears; I couldn’t hear beyond my own landscape. I still love Mobb Deep. “Shook Ones” will always have its place in my heart, on playlists inspired by angry moments, by the claustrophobia of New York, by the cold and the gray. I’ll save “Shook Ones” for trips back home. For L.A. days, I’ve got “The Recipe.”