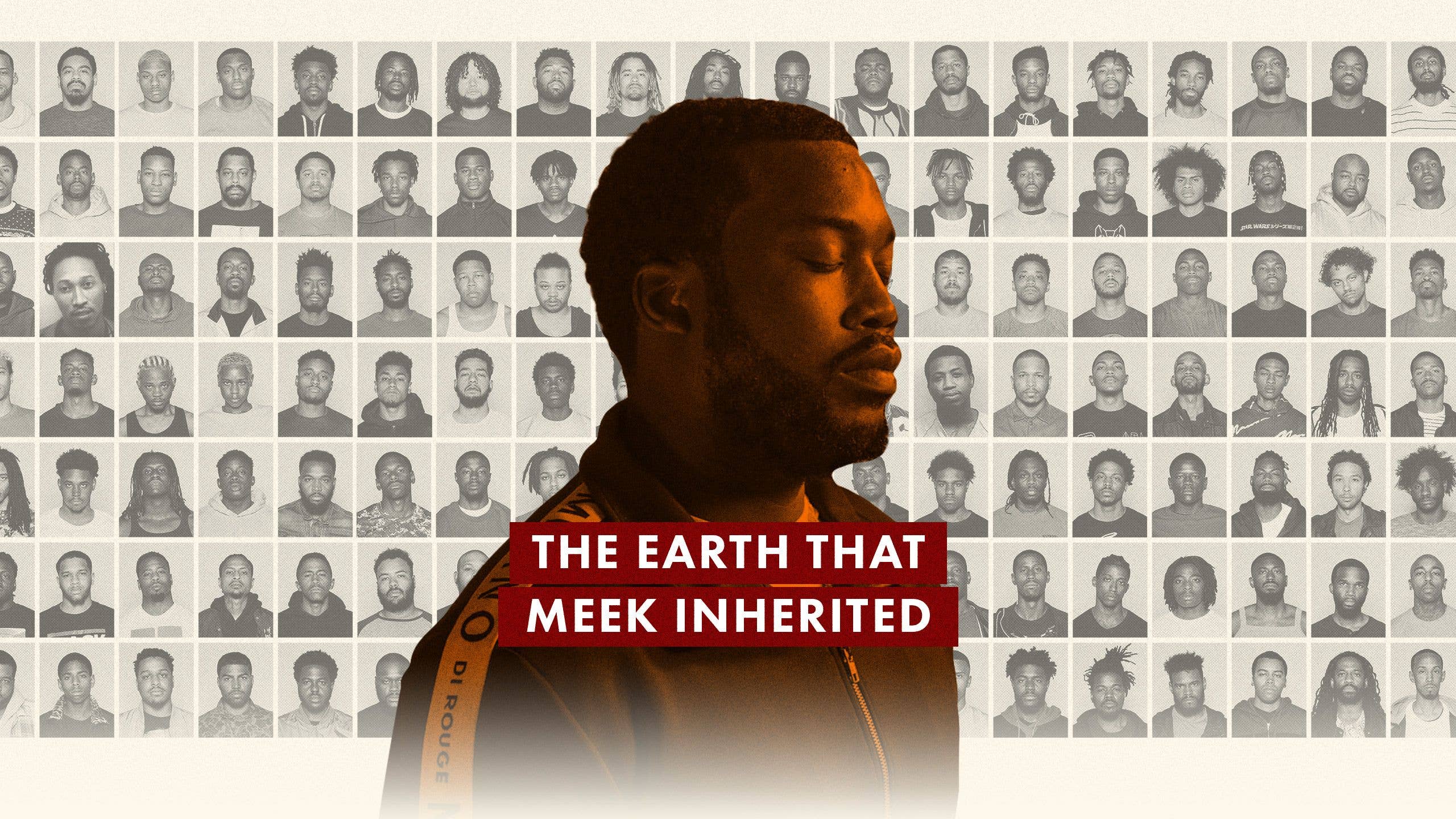

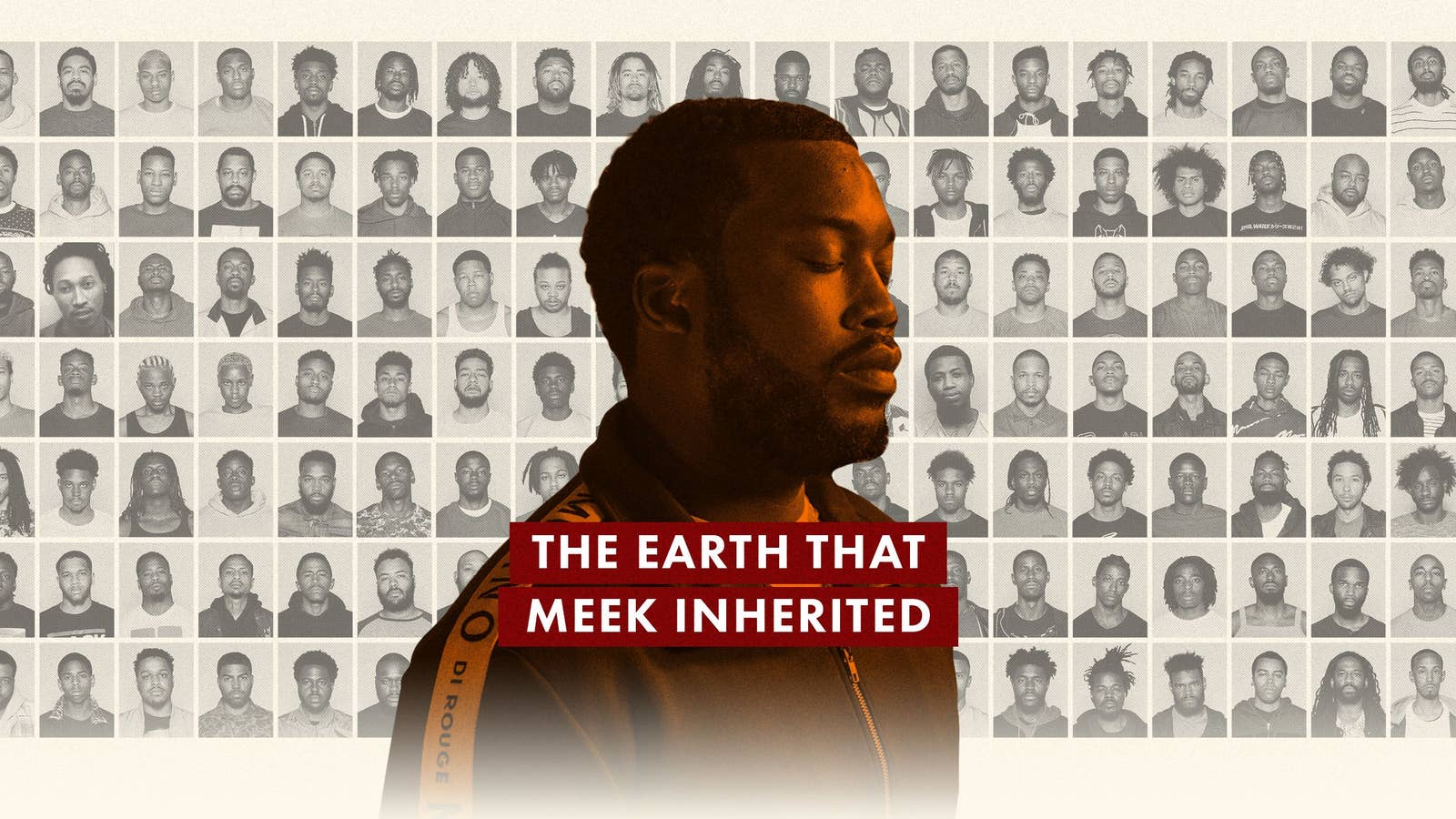

Through music, reportage, and social media, Meek Mill’s battle with the so-called justice system has been thoroughly documented. However, his five-part docuseries, Free Meek, debuting August 9th on Amazon Prime Video, happens to offer a more panoramic view of the 32 year-old’s journey in life.

Like a satisfying screen-adaptation of a novel, all the scenes you’d expect to appear in the series are there: the infamous wheelie on Dyckman, the bizarre Boyz II Men remix request from Judge Genece Brinkley, as well as the triumphant helicopter ride from prison to the 76ers’ sideline. But what viewers may be surprised to see (in reenacted detail, no less) is the murder of Meek’s father, the indignity of poverty, and the vulnerability of batttle rapping. After a swift and single binge, the biggest takeaway from the series is clear: for Meek Mill, the concept of hardship not only predates his 2007 arrest, it ultimately informed the way he coped with and rationalized the injustice he suffered while waiting to see his conviction overturned.

"You get involved in the system and see it’s the same thing as the streets… They’re just using their hate in a different way."

On a quiet evening at Roc Nation’s New York headquarters, the Philadelphia-bred artist insists “it’s normal to me” when the topic of post-prison trauma comes up in conversation. “I come from being in fucked up positions,” he explains. “People dying everyday, not being able to make rent—shit like that. So I don’t think the stress level now matches what I came from.”

If one were to study Meek Mill’s media appearances as closely as fans analyze his music, they’d notice the emotional cadence in which he describes growing up impoverished is almost identical to the way he describes living life imprisoned. As Meek explains to me, without mincing words, “I come from poverty,” I’m reminded of the tenor in which he’s spent the past year explaining to other interviewers what it was like to be locked in a cell for 23 hours a day, or anecdotal recollections of shocking Sixers partner Michael Rubin with the fact that prisoners sometimes work for as little as eight cents an hour. On Timeout with Taylor Rooks, one of Meek’s first interviews after being released on bail in April 2018, he revealed to the reporter that it was “embarrassing” to have people visit the facility and see him incarcerated.

Although Meek denounces the inhumanity of the criminal justice system, the reform advocate maintains his belief that certain people do deserve the harsh realities of prison. To him, and many others, violent offenders belong behind bars, while folks pinched for technical probation violations don’t.

“I ain’t saying there should be no such thing as prison,” he says. “You got people who kill, people who murder, people who do the wrong things in life… I’m not here speaking for a person that’s a lowlife, a person who doesn’t have anything to offer society. I’m speaking for people who are actually trying to do something with their lives and make it out of tough situations.”

According to The New York Times, “fifteen and a half billion dollars of the proposed budget for the coming year will go to corrections, and 40 percent of that goes to staff salaries alone.” An optimistic mind could work itself into a frenzy considering how low-income, high-crime communities would be affected if that $15.5 billion were spent on education, healthcare, and housing instead of prisons, probation, and parole. If the massive amount of resources that are spent on prisons and state supervision each year were instead spent on improving suffering communities, far fewer people would find themselves in the system.

In his Amazon docuseries, Meek admits, “I was raised on survival. I was raised on how to stay alive.” If society were more interested in providing neighborhoods like North Philadelphia with opportunities to thrive, innocent people trying to make it out of the struggle wouldn’t get caught in the crosshairs of America’s war on crime.

Perhaps in that utopia, a version of North Philly exists where Meek Mill is raised in an environment where he isn’t surrounded by people who have to rely on crime to survive. This would be a Philadelphia where he doesn’t grow up in substandard public housing; where his father doesn’t have to rob drug dealers for a living, and isn’t gunned down in the street as a result; where trap houses don’t exist, and an 18 year-old kid isn’t dragged inside of one to be beaten with his hands cuffed behind his back.

Ultimately, this would be a Philadelphia where #FREEMEEK never becomes a hashtag or call to action; where Meek’s connections to JAY-Z and Michael Rubin are exclusive to friendships and business associations, and the founding of their REFORM Alliance feels unnecessary; where albums like Championships are true odes to the American dream, instead of celebrations of nightmares deferred.

"I’m speaking for people who are actually trying to do something with their lives and make it out of tough situations."

Yet Philadelphia’s criminal justice system remains broken. What’s most disappointing about the court’s status quo is, in some instances, it’s maintained by gatekeepers who share the same complexion as its victims, but lack empathy for the racial and economic barriers they encounter.

Before Meek was granted a new trial and judge in July, he endured cruel behavior from his presiding judge, Genece Brinkley, and arresting officer, Reginald Graham—both of whom are black. With allegations of bias by Brinkley and recent reports of Graham having a corrupt record, the rapper sees little difference between the conduct of those particular officers of the court and that of the criminals they’ve prosecuted.

“It’s disgusting,” he fumes, to have people who look like him inflict that sort of harm without hesitation, but it isn’t uncommon. “You come up in a neighborhood full of self-hate and black-on-black crime… Then you get involved in the system and see it’s the same thing as the streets. It’s the same type of mentality. They’re just using their hate in a different way.”