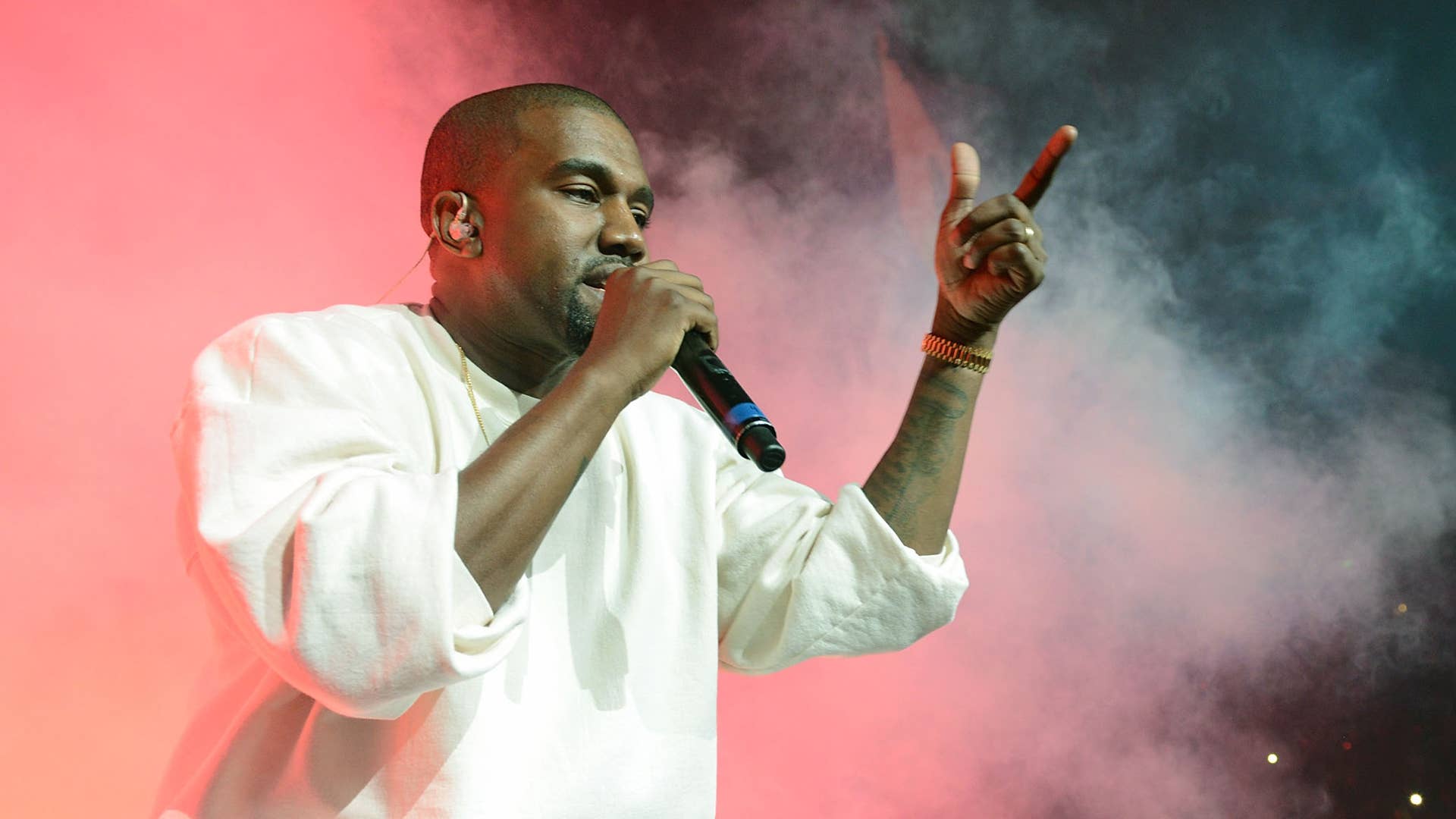

In a tweet on Tuesday night, Kanye West shared a screenshot of a text from an unknown person, appearing to spill a possible litigation strategy against two major record labels, suggesting that he was trying to buy back his master recordings from the labels at an unknown price: “If Taylor [Swift]’s cost $300 million yours would cost a lot more I assume.”

In follow-up tweets, Kanye claimed that Universal Music Group wouldn’t provide him an opportunity to buy back his masters, but he was trying. By Wednesday morning, a few elusive tweets about ending his contract had spiraled into a full-blown tweetstorm, ranging from general commentary about ownership of masters, to requests for meetings with billionaires, and culminating in the release of over 100 pages of contractual documents. Kanye shared a 2005 superseding agreement of his original 2002 recording contract and a handful of subsequent amendments in which his label exercised additional options for further records.

Apart from the astounding multi-million dollar advances, the agreements overall aren’t atypical for recording artists. In particular, the fact that Kanye doesn’t own his masters is woefully standard in major label recording agreements. Masters, or the “master recordings,” represent one piece of the web of royalty-earning [objects] that tend to make up a recording contract. Music copyright law provides that all songs are made up of a master and a composition. The master is the physical recording and the composition is the tune. While compositions often remain in the hands of the artists who wrote them, master ownership by artists has historically been rare. However, in more recent years, some artists with leverage have been able to negotiate more favorable terms. In fact, 21 Savage and SZA were so successful in popularizing themselves prior to a record deal that they were able to maintain ownership of their masters in negotiation.

Kanye’s goal here is unclear. Like much of his behavior in 2020, he appears to have gone full chaos-mode; blatantly violating the agreement’s confidentiality obligations and sharing financial terms, conceivably in order to shame his label, Universal Music Group, into succumbing to his demands to own his masters and renegotiate elements of his existing agreement. However, perhaps accidentally wedged in between poop emojis, bible verses, and a video of him purportedly urinating on a Grammy, this gesture could be a major step towards democratizing entertainment contracts.

Kanye’s predicament is not unlike that of one of his former adversaries. In 2019, Taylor Swift took to her Tumblr account to share her own frustration around failed attempts to buy back her masters, and advised young artists of the importance around such terms in a contract. Kanye’s tweet warning—“When you sign a music deal you sign away your rights. Without the masters you can’t do anything with your own music”—eerily rings of Taylor’s 2019 feud with Scooter Braun (coincidentally, Kanye West’s ex-manager) in 2019. After Braun procured ownership of Swift’s master recordings in a label purchase, he had allegedly refused to allow Swift use of her songs in a documentary about herself.

The “why now” part of the equation is easier to ascertain. West’s tweets indicate that artists need to own their masters now more than ever because their revenue streams derived from touring have dried up due to the COVID-19 pandemic. “[A]rtist [sic] are starving without tours,” he wrote. Kanye further laments the fact that labels, as owners of his work, are taking advantage of their position of power to keep artists under their proverbial thumb: “A standard record deal is a trap to NEVER have you recoup, and there’s all these hidden costs like the “distribution fees” many labels put in their contracts to make even more money off our work without even trying.”

Transparency is a powerful tool to undermine injustice.

While the contract-dump and subsequent tweetstorm may not be successful in and of itself in getting Kanye’s masters back (and of course, any lawyer would cringe at his tweet screenshotting his lawyer’s master strategy to claim UMG is in breach of their contract) there is a broader implication to his actions. His apparent intention to commiserate with other Black artists and athletes who are stuck in bad contractual arrangements is a more clear call to collective action. “Brothers let’s stand together for real ... there is no NBA or music industry without black people ... fair contracts matter ... ownership matters.” “Ima go get our masters ... for all artist ... pray for me,” he wrote.

Transparency is a powerful tool to undermine injustice. In a workplace, for example, any successful organizing around unfair contracts starts from understanding the discrepancies between employees; until one knows how much everyone around them is getting paid, they don’t know if they are underpaid. Accordingly, his attention to this issue and sunlight around his recording agreement could be a first step in getting other artists to the table to talk about what their ideal contractual terms are, by highlighting who isn’t getting them. And if even Kanye West feels powerless in this instance, it’s exceedingly likely that he’s not alone. When Taylor took to social media to tell her story last year, she did so allegedly with the hopes that her words would reach “young artists or kids with musical dreams” so they could “learn about how to better protect themselves in a negotiation.” “You deserve to own the art you make,” she signed off. Her attention to this issue received a lot of press, but change remains slow in an industry that has much to profit off its commitment to this controversial provision.

Even now, Kanye appears to be eliciting responses as well: Hit-Boy, whose career began under West’s auspices at GOOD Music, responded that UMG had held him in an unfair contract for the last 14 years. Interestingly, Taylor Swift issued a gleaming press release about her signing with UMG in 2018, highlighting their agreement in which she would own her own masters. In order to successfully bargain for less sophisticated artists, a start would probably require most of music’s heavy hitters coalescing around and pushing forward standard contractual terms. Kanye, however, may not have always reflected this artists-rights forward approach. At least one artist suggested on Twitter that West, a label owner in his own right, replicated some of the predatory (albeit perhaps market) contractual provisions in some of GOOD Music’s signings.

Kanye and Taylor are not alone in this perspective. For many years, artists have bemoaned this feature of agreements. In 2015, when Prince exclusively released his new record HitNRun to Tidal, he likened recording agreements to indentured servitude and said, “I would tell any young artist...don't sign.” But it’s not a surprise that even in the face of these kinds of warnings, young artists continue to sign the contracts. At this time, major record labels remain the most promising option for them. When it launched in 2015, Tidal was the first of its kind: an artist owned streaming platform that offered artists a way to profit differently from streaming. The platform however took aim at Spotify instead of the major label machine, and has consequently fallen somewhat flat in its mission. It’s not hard to see that artists might be better served by joining together and requiring a baseline of contractual terms—screen actors and much of the film industry have done it—but like Kanye, many of the largest artists often find themselves on both sides of the contracts. And perhaps, there is just too much upside to undermine the status quo.

Jessica Meiselman is a New York licensed attorney specializing in entertainment and intellectual property issues.