"Sampling is just a longer term for theft. Anybody who can honestly say sampling is some sort of creativity has never done anything creative." —Mark Volman of The Turtles to The Los Angeles Times in 1990

“A good composer does not imitate; he steals.” —Igor Stravinsky, composer and conductor

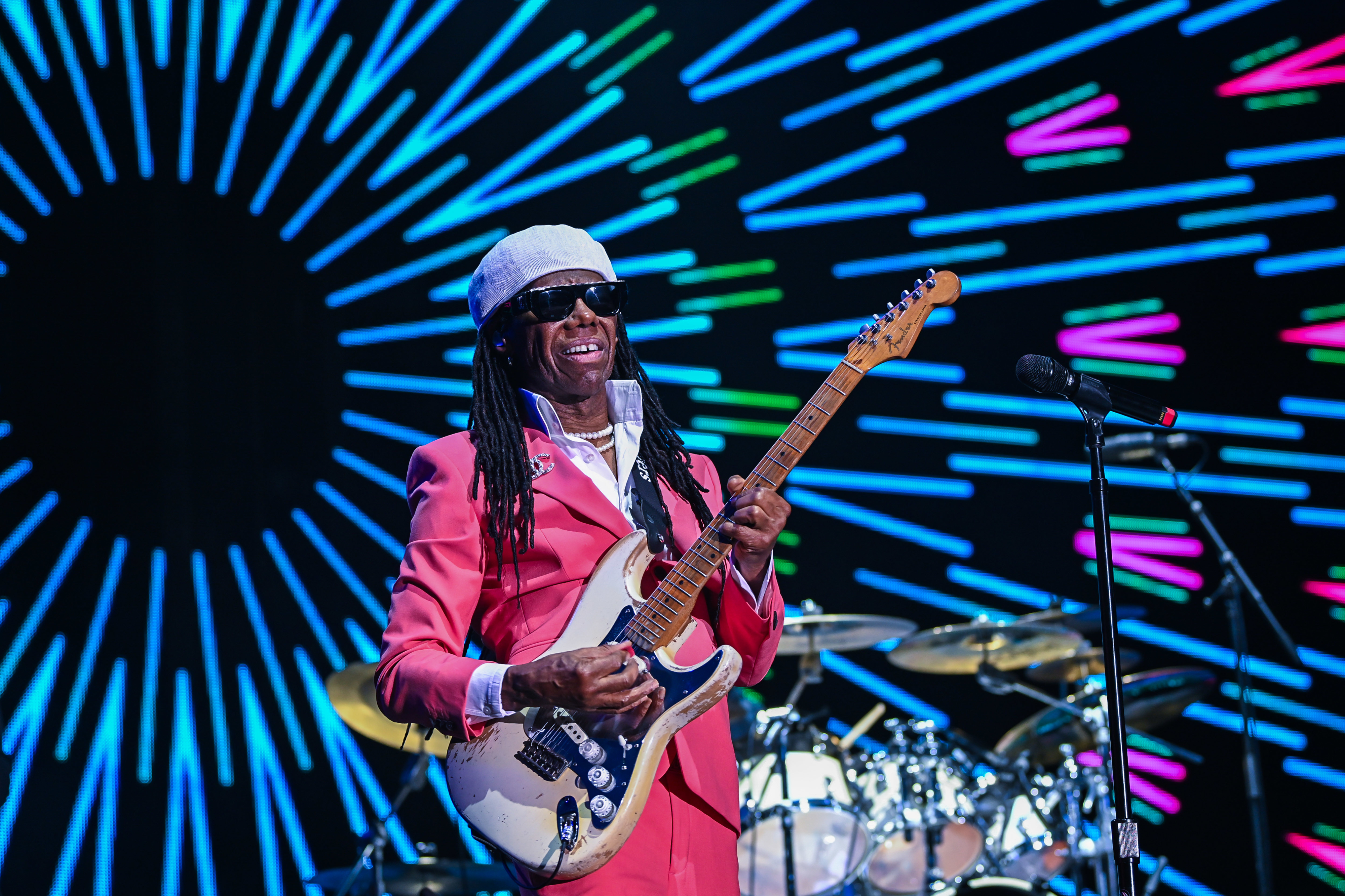

One of the greatest moments in the legendary life of Nile Rodgers happened when he was snoozing on an airplane and the late, great John Singleton placed headphones on his ears. The producer, guitarist, and composer behind dozens of hits awoke to a song he’d never heard before: The Notorious B.I.G.’s “Mo Money, Mo Problems.” Rodgers was intrigued by the song’s concept and impressed by its hook. The beat sounded similar to one he’d made 17 years earlier. That’s because “Mo Money, Mo Problems” samples Diana Ross’ “I’m Coming Out”—a top-five Hot 100 hit from 1980 that Rodgers, along with his Chic bandmate Bernard Edwards, wrote and produced. Rodgers' music had been sampled many times before, and when he heard Puffy's take on "I'm Coming Out," the last thing he considered was a financial return.

“I thought about the artistry and what it took to conceive and assemble such a piece,” said Rodgers, during a Zoom call. “I was in awe of how clever it sounded. I was simply blown away. I couldn't stop thinking about how genius it was.”

“Mo Money, Mo Problems” peaked at number one and is now considered a hip-hop classic, but not everyone saw the genius in it like Rodgers did. In the late ’90s, Puff Daddy and his team of Hitmen perfected the art of, to paraphrase Puff on “Feel So Good,” taking hits from the ‘80s and making them sound so crazy. As Bad Boy Records became one of the biggest labels in music, not just rap, Puff began suffering from success, criticized by hip-hop purists who felt he’d bastardized the unwritten rules of hip-hop sampling. The Source went as far as to call him “the biggest biter ever.” Non-hip-hop fans didn’t consider sampling to be an artform at all.

The backlash Puff experienced in the late ’90s is not unlike the criticism some rappers are facing today. Except they aren’t always taking decade-old disco, pop, and rock hits and reworking them into a hip-hop sound. They’re sometimes sampling other rap songs or songs of other genres that have been sampled before, often to the dismay of social media commenters who decry the act as “lazy.” Artists like NLE Choppa, SZA, and Coi Leray have been rebuked on social media for sampling or interpolating 2000s rap classics from Nelly, OutKast, and Jay-Z (respectively). They’re not the only ones catching flak. A TikTok video breaking down a song's sample will lead to dozens of comments likening sampling to stealing, stripping the song of any artistic merit.

Jarred Jermaine worked as a producer and engineer for years before COVID quarantine boredom led him to break down samples on TikTok. He wasn’t sure about the venture at first because he assumed most people knew the source material of hits. To his surprise, his videos took off, and he’s now a full-time influencer with 5.3 million followers. But every single time he posts a video, his comments section gets predictable responses. “They're like, ‘Wow, they just keep stealing,’” says Jermaine, who shares that most of his audience is Gen Z and even Gen A (born 2010–24). “They’re like, ‘Dang, this is just straight plagiarism,’ or, ‘No talent.’”

Jermaine gets so many of these comments that he doesn’t have the energy to respond to them all. His view, though, is decidedly different. “It actually does take talent to manipulate another song into a new piece of creative content, which is a new song for a new generation,” he explains. “A lot of samples actually are changed. They add things to it; they take things out; they chop it up. I think when people visualize samples, they [think artists] just copy and paste.”

"It actually does take talent to manipulate another song into a new piece of creative content, which is a new song for a new generation."

To Jermaine’s point, Puffy and producer Stevie J didn’t simply lift “I’m Coming Out.” They deconstructed the loop by isolating Rogers’ signature guitar clucking, then had an uncredited Kelly Price re-sing the “I’m coming!” intro, and added an original chorus on top. The beat mimics the original, but the Bad Boy version has a brighter, 48-track feel that shines like a Rollie on the wrist. They also recontextualized the source material. Ross’ original served as an LGBTQ anthem and a sendoff to her former label boss Berry Gordy, while Biggie’s crossover hit is about the spoils of getting rich and never wanting to stop, even if the feds are on your ass. I’m coming!

“The recontextualization part, that's always been the academic argument for sampling,” said DJ A-Trak, founder of Fool’s Gold Records. “Someone like DJ Premier, he’s chopping stuff up to a point where it's unrecognizable. If you go to Gang Starr’s The ? Remainz and you listen to the Bob James sample and what he did with it, you're like, ‘How did you think of that? How did you take half a bar and grab a record that felt so happy and make it sound so angry?’ Like, of course that's art.”

The question of whether sampling is art might feel like a settled debate to some, but it’s clearly not to others. Social media commentators reacting to sampled songs seem to think they’re making a novel argument about the nature of art. Others seem convinced that music was more creative before. But this is actually an old argument. The comments read like they’re lifted from subtly racist, anti-hip-hop hit pieces that once littered music magazines. It’s actually the same old song.

“I am a musician. I don’t sample.” —Prince, 1998, BET Tonight with Tavis Smiley

The story of hip-hop sampling is intertwined with the story of hip-hop itself. In the late ’70s, DJs like Kool Herc and Grandmaster Flash threw parties where they isolated and looped breaks from funk, soul, and disco records to create breakbeats for MCs to rap over. This made sampling foundational to hip-hop in a way that it isn’t to most other genres, even though music sampling predates hip-hop. Sampling originated in the 1940s. French composer and engineer Pierre Schaeffer is often credited with inventing “musique concrète”—music that used recorded sounds to create compositions. In the 1960s, Jamaican reggae producers like King Tubby and Lee “Scratch” Perry began using recorded reggae rhythms to create “riddim tracks” for DJs, which had a direct influence on early hip-hop thanks to Jamaican immigrants like DJ Kool Herc.

“Hip-hop was based on sampling,” Sean “Puff Daddy/Diddy” Combs tells Complex. “We didn't have any musical programs in our school. We didn't have any instruments. All we had was the two turntables and a record, and we would actually have the vision to take the pieces of the record and reimagine them. That's what sampling is about. For somebody that doesn't understand, it's really just about not having the means. Hip-hop is tied to poverty and wanting to get out of poverty. So when you don't have something, in the true hip-hop frame of mind, you make it happen. That's what the sampling was for us.”

The breakbeats technique—which involved transforming an existing piece of art into a new piece of art—epitomized postmodernism, seamlessly integrating concepts of intertextuality, deconstruction, pastiche, and the blurring of high and low culture. The popularity (and criticism) of breakbeats is reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s screen print technique, where he took famous images of things like Campbell’s Soup cans or Marilyn Monroe’s face and reproduced them with slight variations. Warhol was commenting on mass production, but his process morphed his subjects into something new.

“Hip-hop was based on sampling."

Before there was a rap industry, hip-hop started out in the parks of New York. Rodgers was there. When Debbie Harry and Chris Stein from Blondie invited him to a park jam in 1979, he was told he was going to a “hip hop.” Rodgers, now 71, remembers his response: “I said, ‘What the hell is that?’ And they said, ‘Well, that's where you take something hip and you hop on it.’”

When he got there, he saw MCs lining up as if they were at McDonald’s, all waiting for their chance to rap over the break from Chic’s “Good Times.” “They didn't play any other record,” Rodgers says, still befuddled. “I was just standing there…awestruck. The vibe was unbelievable. I just didn't understand, ‘Why didn't they play another record?’”

Perhaps they didn’t play another record because “Good Times” was the song of the summer, topping the Billboard Hot 100 that August. Or maybe it was because the song had an extended instrumental breakdown, giving DJs enough space to create a breakbeat for rappers to jump on. “It was about finding the break, cutting and scratching it back and forth,” says 57-year-old producer Ron "Amen-Ra" Lawrence. Amen-Ra started DJing in the early ‘80s and later crafted classics like The Notorious B.I.G.’s "Hypnotize" and Faith Evans’ “All Night Long” alongside Puff Daddy as a member of the Hitmen in the ‘90s. “The rapper would rap to the break because that's what it was all about.”

The impact of “Good Times” on hip-hop reached another level a few months later when an enterprising executive named Sylvia Robinson from Sugar Hill Records aspired to recreate the vibe of those park jams on wax and masterminded “Rapper’s Delight.” The song’s beat was not a sample though—it was an interpolation. Robinson instructed her house band to replay the breakdown from “Good Times” for 15 minutes straight to create the beat that became “Rapper’s Delight.”

“When we think of sampling, it's about taking a sample of an actual record and recreating it exactly,” explains Amen-Ra. “In the case of ‘Rapper’s Delight,’ they played the instruments over instead of using a drum machine or sampling machine, so it's not like they sampled it directly. If you replay it exactly, then you would need to clear it with the person who owns the publishing rights.”

Of course, Sylvia Robinson, who produced the song, didn’t actually clear the rights with Nile Rodgers and Bernard Edwards. Today, there are two different laws for sampling (master usage) versus interpolating (publishing rights). For example, when Kanye West couldn’t clear a sample of Lauryn Hill’s "Mystery of Iniquity," he got Syleena Johnson to sing Hill’s vocals over and we got “All Falls Down.” Back in 1979, the clearance process wasn’t as formalized as hip-hop’s commercial viability was unknown—that is, until “Rapper’s Delight” became a phenomenon.

When Rodgers heard “Rapper’s Delight” in 1979, he had a very different experience than he did with “Mo Money, Mo Problems” in 1997. He was at a club when he thought a homage to “Good Times” came on. But what he heard was not a test, someone was rapping to the beat. He assumed it was the DJ, until he spotted him away from the booth, talking to a girl, drinking champagne. He approached the DJ, who told him he’d just copped the record in Harlem and assured him it was the “hottest thing on the street.” “I looked at the label, but I didn't see my name on it,” said Rodgers, who likened lifting “Good Times” to sticking a scene from Star Wars in your music video. “I went from ‘This is clever’ to ‘Damn, where's my name on the copyright?’ All of this happened in a matter of maybe 10, 15 minutes.”

Rodgers began pursuing a lawsuit, traversing through the shady tunnels of the music industry. His final destination wasn’t Sylvia Robinson or her husband, Joe Robinson. Instead it was infamous music entrepreneur Morris Levy, who funded Sugar Hill Records. Levy was once described as "a notorious crook who swindled artists out of their owed royalties” and partially inspired The Sopranos character Hesh Rabkin. Thankfully, Rodgers had a savvy lawyer, who had dealt with Levy before.

“My lawyer said, 'Your main source of income right now is coming from a 12-inch record,’” said Rodgers, noting that a 12-inch sold for three times as much as a 45 rpm single. “He said, ‘If you just split it with these guys, you'll still be making more money than you've ever made on any single.' They gave us 50 percent, it all went away, and 'Rappers' Delight' remained 'Rappers' Delight.'"

Rodgers and Bernard Edwards getting their names added to the credits of “Rapper’s Delight” is an underrated moment in hip-hop history. Had Rodgers chosen to take his case to court, he might have nipped the hip-hop industry in the bud. At the time, many thought hip-hop was just a fad; having the genre’s first huge hit turn into a legal nightmare probably wouldn’t help convince skeptics. The more money we come across...

While Rodgers wanted credit for his work, he may have also appreciated the creativity of “Rapper’s Delight” because he had also sold DJs remakes of songs with extended breakdowns. Music, like all art, is a part of a never-ending conversation with itself, and it’s not like his music was free of inspiration; the lyrics to “Good Times” reference Milton Ager's "Happy Days Are Here Again" and Al Jolson’s "About a Quarter to Nine." He’s also talked about how he was inspired by Kool & The Gang’s 1974 song "Hollywood Swinging"—the same song Mase later sampled on “Feel So Good.” The conversation continues.

“I didn’t know anything about sampling until people were telling me, ‘Some artist is using your drum pattern.’ I go, ‘Cool.’” — James Brown’s drummer Clyde Stubblefield, in 2009 documentary Copyright Criminals

After the success of “Rapper’s Delight,” hip-hop went from the parks to the record stores across the country and began taking shape as a genre throughout the 1980s. Early records like LL Cool J’s “I Need a Beat” and T La Rock’s “It’s Yours” were driven by drum machines like the LinnDrum and the Oberheim DMX. In the mid-‘80s, when machines like the E-mu SP-1200 and Akai MPC60 were introduced, the game changed. Now you didn’t need a DJ to cut a record—you could take a sample and create a loop. This opened the floodgates of hip-hop sampling, including a roaring river of music from James Brown, George Clinton, and The Isley Brothers. “Whatever we were doing in the street as a DJ, the sampling technology took it out of the park and just put it on wax,” said Amen-Ra. “Every time technology comes, it’s able to move things up a notch. The sampler is just a tool to take it to the next level so the masses could hear it.”

The sampler became the hammer that producers like Marley Marl, Dr. Dre, and The Bomb Squad wielded to forge classics for Big Daddy Kane, N.W.A, and Public Enemy. Songs like “Ain’t No Half-Steppin,’” “Fuck Tha Police,” and “Fight the Power” are stuffed with snippets of other songs. According to WhoSampled, “Fight the Power” has 22 samples alone. Those songs were sound collages: The producers used a snare from here, a riff from there, and a James Brown grunt to create a new composition that was past, present, and future all at once. Hip-hop matured as an art form throughout this period.

"Every time technology comes, it’s able to move things up a notch. The sampler is just a tool to take it to the next level so the masses could hear it."

As soon as things started to settle, they changed again. In the early ‘90s, it wasn’t just technology that evolved; it was the legal ramifications around sampling. Artists like Biz Markie, De La Soul, and yes, even Vanilla Ice ran into copyright lawsuits and got sued by artists they sampled from. While not every artist wanted their music to be associated with hip-hop (some samples are just never cleared), everyone else wanted their credit and share of the profits. The rulings and out-of-court settlements made it evident that all samples must be cleared with the original copyright holders—the same issue Rodgers originally had with “Rapper’s Delight.” Suddenly, sampling wasn't a cheap alternative. The DJs in the Bronx who couldn’t afford instruments or musical training but could make something out of nothing using this postmodern technique now had to climb complicated legal hurdles to make hip-hop music.

The legal woes distorted the sound of hip-hop, though not the spirit. For one, it kept De La Soul’s masterpiece 3 Feet High and Rising off the shelves and off streaming until recently. When De La made their 1996 album, Stakes Is High, they had to go through a list of artists they wanted to sample, only for their label to tell them to avoid certain legal minefields. It’s one reason why younger audiences might struggle to connect with De La or Public Enemy’s music: Having a dozen samples got complicated and expensive, so hip-hop gradually stopped sounding that way, and the reference points were eventually lost. This led to a shift toward more interpolation with live instrumentation and fewer samples per song, like Dr. Dre did with The Chronic. Some producers opted to manipulate sounds to the point that it was nearly impossible to identify the source material (thus the birth of the sample snitch). Others started digging deeper into crates to find more obscure sounds.

“You get to the early ‘90s—you're starting to get like Diamond D, Pete Rock, and Gang Starr sampling jazz. That's a pretty big change,” said DJ A-Trak. “By the mid-’90s, you got producers sampling all kinds of deeper, weirder shit. It's not even jazz anymore, especially once you get into the era of production where it's lifting sounds from like any kind of weird sonic. All that is changing every two, three years.”

Hip-hop evolved by leaps and bounds throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s. By the late ‘90s, the genre had proven it wasn’t just commercially viable but commercially dominant, with hardcore rappers on Death Row and Bad Boy showing they could be Billboard heavy hitters. Somewhere along the way, there became rules. Not laws, like ones about copyright infringement or mechanical royalties written in a voluminous library somewhere. No, the hip-hop rules were unwritten, like the rule that says rappers have to write their own rhymes. The rules said you weren’t supposed to sample something easily recognizable, or something recent, or something someone else sampled. None of this really adds up since “Rapper’s Delight” and “Good Times” were released months apart, and “Good Times” was a huge hit while “Rapper’s Delight” was actually ghostwritten. Plus, dozens of rap songs sampled James Brown’s “Funky Drummer” or The Honey Drippers’ “Impeach the President.” Yet this code of ethics persisted.

“I remember if you were a dude in the ‘90s, you weren't even supposed to sample drums from like the open part of a Premier or a Dr. Dre joint,” recalls A-Trak. “People would be like, ‘No, you have to go and sample the original break.’ I remember producers playing beats to each other, and the one that's listening, telling the dude playing his beat, 'You jacked the snare off this—you can't do that.' It's ridiculous to think about that now.”

Rules were meant to be broken, and no one broke them quite like Puffy did. Equipped with a talented roster of producers, singers, and rappers—as well as the ambition to dominate the airwaves—he started doing what you weren’t supposed to do: sampling hit songs. Bad Boy embodied a newer generation; their influences weren’t solely rooted in the '70s soul, but were equally, if not more, inspired by the pop music of the '80s. Beyond “I’m Coming Out,” they flipped other chart toppers like David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” for “Been Around the World,” Mtume’s R&B hit “Juicy Fruit” for Biggie’s “Juicy,” and most infamously, The Police’s “Every Breath You Take” for Puff’s “I’ll Be Missing You.”

"All we had was the two turntables and a record, and we would actually have the vision to take the pieces of the record and reimagine them. That's what sampling is about."

Earlier this year, a clip of Sting confirming a rumor about Puffy paying him on a daily basis for the sample went viral; Diddy even tweeted about it. In the clip, Sting noted that Diddy asked permission but only after the fact. “Sometimes we had a habit of releasing the record first and taking care of the paperwork later, which in hindsight wasn't the smartest thing to do,” admits Amen-Ra, who learned just how costly it could be when he sampled David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance.”

“When we released ‘Been Around the World,’ David Bowie and Nile Rodgers took 100 percent of the publishing, leaving us with nothing,” he says. “The record was released without being cleared, so they took advantage of the situation.” Amen smartened up when he sampled Rodgers again for Faith Evans’ “Love Like This,” clearing it first and letting Rodgers take the typical 50 percent. But this was a lesson young hip-hop artists have had to learn time and again: In 2018, Sting took the majority of the publishing from Juice WRLD’s Nick Mira–produced breakout hit “Lucid Dreams,” which sampled his 1993 hit "Shape of My Heart"—a song Nas and Trackmasters had already flipped in ’96 for “The Message.”

Legal mishaps aside, the more Puff ruled the charts, the more hate he got.

“I think the reason why Puff got a bad rap in that era when he was redoing 'Let's Dance' and Led Zeppelin’s 'Kashmir’ is that he was grabbing records that were already enormous hits,” said A-Trak. “Whereas everyone always romanticized grabbing the forgotten record that never quite made it, giving it new life, and turning it into a smash. When Pete Rock grabbed Tom Scott’s horns from 'Today' and turned it into 'They Reminisce Over You,’ you're just like, ‘Oh man, how?’ That first record wasn't huge; now you turn it into this generational anthem. That's kind of the dream.”

That romanticized dream may be why many felt Bad Boy's sample choices felt obvious. Of course using The Isley Brothers’ “Between the Sheets” was going to make for a great song—it’s so obvious when you hear “Big Poppa.” What’s often forgotten is that “Between the Sheets” was sampled a dozen times before —by Audio Two, UGK, A Tribe Called Quest, and more—yet none of those songs are as revered as “Big Poppa.” Artists also had to win the approval of the artists they sampled: Herb Albert’s “Rise” was the rare instrumental that went No. 1. Many rappers tried to sample it, but Herb and his brother Randy denied every single one of them—until Randy heard a tape of Biggie rapping “Hypnotize.”

Yes, “Every Breath You Take” was a huge hit, topping the charts for eight weeks. Yet sampling it didn’t do much for MC Peaches in ‘91 or Karmah in ’97. “I’ll Be Missing You” was an even bigger hit than the original, hitting No. 1 for 11 weeks. And again, recontextualization: “Every Breath You Take” is thought of as a romantic song, but Sting himself called it “rather evil” because it’s about “surveillance and ownership,” influenced by his pending divorce after having an affair with his wife’s best friend. “Missing You” is totally different; it’s a ballad for a fallen friend who was viciously gunned down in public with a hook sung by his widow.

Using a classic song didn’t always work wonders. Puffy’s formula began showing diminishing returns the following year when he teamed up with Led Zeppelin’s Jimmy Page for “Come With Me.” The song sampled Zeppelin’s “Kashmir” and peaked in the Top 5, but it’s not beloved like other Bad Boy hits from that era. Chuck D called it a “debacle.” But no idea’s truly original.

“Zeppelin fans freaked out: ‘What are you doing taking this classic epic song and turning it into a pop song?’” said Merck Mercuriadis, a music industry executive and Nile Rodgers’ manager. “They don't know that Jimmy Page and Robert Plant based all their songs on great blues songs from the ‘40s and ‘50s. They didn't even give credit to those blues players, similar to how Nile didn't get credit, because they were young and didn't know the proper process. As they grew older, they realized they needed to do the right thing, and they included names like Willie Dixon on the records. Where were the Muddy Waters fans freaking out in 1958, 1968, or 1970 when Zeppelin were effectively rewriting Willie Dixon songs?”

Sometimes, even giving credit isn’t enough credit. Puffy and Sting say they’re great friends, and Sting praised “Missing You”—lost in the sauce is The Police’s guitarist, Andy Summers, who called the song a "major rip-off." It’s Summers’ guitar playing that’s actually sampled, not Sting’s singing (which Faith Evans interpolates), but Sting owns the publishing. It’s reminiscent of what happened with James Brown’s “Funky Drummer.” One of the most sampled songs ever, “Funky Drummer” probably made a fortune for Brown and his estate. But it’s not Brown being sampled as much as his drummer, Clyde Stubbifeld, who was only paid once as a session musician. In the documentary Copyright Criminals, Stubblefield remarked, “They say I’m the world’s most sampled drummer. I haven’t gotten a penny for it though.”

Bad Boy’s reign eventually came to an end, though not before Puff’s pop formula brought hip-hop permanently into the mainstream. Hip-hop’s rise did lift every voice. The music of Rodgers, George Clinton, James Brown, and others got a second life through all the rappers that used their music. They all probably made a lot of money. Mercuriadis estimates that Rodgers made as much off being sampled as he did from his original hits.

“Sampling is getting to the point it’s out of hand too. I mean, pretty soon we’ll be sampling the sample that was already sampled.” —Prince in 1999 to MTV News

There’s a story A-Trak has probably told too many times but is worth repeating. He’s often credited for giving Kanye West the sample for “Stronger,” though that’s not exactly how it happened. While on tour with Kanye in Europe, A-Trak realized Kanye had never heard Daft Punk’s 2001 worldwide hit “Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger.” When he played him the song, he was surprised that Kanye—who first blew up as a producer speeding up soul records—said he wanted to use it. “I was still in a sort of ‘90s mentality of like, you have to dig for a sample that people haven't heard before, or you have to flip it,” recalls A-Trak. Kanye made his version anyway, which he called “Stronger,” and when A-Trak heard the final version he saw the vision. “Like, I get it. You turned it into some different shit—like, you didn't just jack it. It was definitely flipped enough where I was like, ‘OK, I'm with this.’”

The process of that song made A-Trak realize he needed to revisit those unwritten rules from the ’90s. But that was 15 years ago. Hip-hop has evolved since Puff ruled the world and Kanye graduated, but not at the dramatic artistic pace it did in the ’80s and ’90s. If you compare a rap record like Boogie Down Productions’ 1987 track “The Bridge Is Over” to Big Pun’s 1998 hit “Still Not a Player,” they don’t sound like they were made a decade apart—they sound like they were made a century apart. Meanwhile, my conversation with A-Trak took place the day after Travis Scott dropped Utopia, one of the best rap albums of the year—which was immediately noted for sounding like Kanye West’s Yeezus, a decade-old album.

“If someone's making a record in 1994 and sampling something from 1974, there’s recontextualization, [by turning] a record that was made before hip-hop existed into a hip-hop sound,” said A-Trak, who loves the gut feeling guiding today’s producers, who probably are sampling songs from a folder of tracks a friend sent them. “If you transpose the same time gap and it's 2023, you're sampling something from 20 years ago—that's 2003. That doesn't even feel that distant. Ever since the internet really took over our lives and the way that we consume culture, there's this constant, weird paradox where in some ways time feels sped up and trends move faster than before. A decade now seems to come and go in three or four years. But there's also this weird sense of time being stretched out.”

Time is a flat circle—that might be why the sampling debate has come back around. Today, artists like Metro Boomin, Ice Spice, and Ozuna have all sampled Bad Boy songs, effectively biting “the biggest biter of all time.” Young Miko recently interpolated the opening bars from “Rapper’s Delight.” Young artists today grew up to and were inspired by music that came out in the ’90s and increasingly the 2000s. “The older generation will probably say it's wack because they cannot understand today's music,” said Amen-Ra. “They're not really in touch with what's going on; just like when we did it, they couldn't get with it. They told us that it was wack too.”

No matter the criticism, people like Puffy remain unfazed.

“That’s the importance of being able to sample, because it allows you to time travel; it allows you to bring a feeling back that you may have felt as a kid,” said Puffy. “That's the magic of it. So, as a sampler, I'm a magician.”

"As a sampler, I'm a magician.”

As debates rage on, ideas about credit and inspiration have gotten more complicated after the “Blurred Lines” lawsuit. But sampling is more omnipresent than before, Mercuriadis estimates that 20 to 25 percent of the songs on the Hot 100 these days will have some level of sampling or interpolation. Its impact is beyond hip-hop. One of the biggest dance records of last year was David Guetta’s “I’m Good (Blue),” which samples Eiffel 65’s 1998 smash hit “Blue (Da Ba Dee).”

“In order to get attention span, more and more artists are finding it necessary to interpolate and sample so that there's a level of familiarity,” explains Mercuriadis, who notes that the majority of consumption on streaming is actually catalog, songs that are older than five years. “Coi Leray wrote a dope record with ‘Players,’ but that Grandmaster Flash sample immediately puts you in the frame where you feel comfortable. It gave someone something that they could sink their teeth into; then it gave them something fresh to go with it.”

Familiarity is vital in an era of overflowing content. The entire history of recorded music is at our fingertips, plus there are thousands of new songs being uploaded every day.

“People are hungry for the same but different,” said Jermaine. “Hollywood just keeps making reboots. How come they're not creating original movies as much as they're doing sequels to Fast & Furious? Think about that and apply that to music; why are people sampling so much? It just fucking works.”

Mercuriadis and Rodgers know just how well it works. They started their company, Hipgnosis Songs Fund, in 2018, which manages 150 of the most successful song catalogs. Mercuriadis highlights the success the company had last year with Nicki Minaj’s No. 1 hit “Super Freaky Girl,” which flipped Rick James’ “Super Freak”—a song in the Hipgnosis library. James' original had been previously flipped for another smash hit, MC Hammer’s “U Can’t Touch This.” To critics, this is a perfect example of the lack of originality in music today, but Mercuriadis notes that while “Super Freaky Girls” might net hundreds of millions of streams, it also likely introduced a new generation to Rick James and MC Hammer and likely yielded them millions of streams as well.

“That emotional connection that people have with music can help you have a hit in 2023 if you sample or interpolate it correctly, which is why you see it happening constantly,” said Mercuriadis, who thinks Arabic music will play a big role in the next wave of sounds and adds that 50 Cent’s catalog is one of their most requested samples right now. “It goes back to the roots of what Nile always says: Anything that makes the Top 40 is art because it means something to people.”

Still, sampling may never be seen as art to skeptics who believe Nile Rodgers playing on his guitar is superior to Puff Daddy sampling Rodgers’ guitar riffs. But they miss the point of both. The medium is the message. Crafting something by hand is not inherently superior to using a machine. As the late Shock G once reasoned: “Perhaps it's easier to take a piece of music than it is to learn how to play a guitar, true. Just like it's probably easier to snap a picture with that camera than it is to actually paint a picture. But what the photographer is to the painter is what the modern producer, and DJ, and computer musician is to the instrumentalist.”

For hip-hop fans who do believe in sampling but think the younger generation is just doing it poorly, they might not be entirely wrong. When NLE Choppa sampled Nelly’s “Hot in Herre” for “It’s Getting Hot,” he didn’t just sample the beat—he rapped in the same cadence, used a similar hook, and dressed up like Nelly in the video. (Nelly seemed to approve.) Some songs work and some just don’t. Maybe Coi Leray’s “Luxury Life” just isn’t as good as “Players,” just like Puff’s “Come With Me” wasn’t as good as “Been Around the World”—but that doesn’t mean they shouldn’t try.

"There is a way to sample a rap record to make a new rap record in a way that has artistry."

Sampling is popular, but it’s not the only way to make music. The aforementioned Utopia has a dozen flips, but another one of 2023’s best rap albums, Gunna’s A Gift and a Curse, has no credited samples. In fact, trap producers typically don’t sample much. Last year, Future flipped a Tems record for his biggest hit ever, but his album I Never Liked You had only one other sample. Finally, the sound of hip-hop can (hopefully) continue to evolve. While some fear the advent of A.I. in music, Amen-Ra has embraced the technology, experimenting with using A.I. to isolate sounds in songs he couldn’t do before.

“There's a big element of this that's a little bit intangible; like, is there something about this choice that feels original? Does it feel inspired?” asks A-Trak. “There is a way to sample a rap record to make a new rap record in a way that has artistry, all the way down to MF Doom sampling J.J. Fad on 'Hoe Cakes.' This stuff is tricky because it can't be oversimplified to, ‘Well, when rap samples rap it's less clever.’ To me, it has to have some recontextualization and a feeling of an inspired, original choice. We shouldn't overly police producers with romanticized rules about what can or can't be sampled. In reality, everything is borrowed or 'jacked' from somewhere else.”

Maybe it’s not a question of “Is sampling real art?” because that’s a question that’s been debated and litigated for decades now. Nor is it a question of whether or not producers are being creative or lazy. When it comes to new music, maybe the better question might be, Who's hot? Who not?