Where do great ideas come from?

How do musicians turn strokes of inspiration into beautiful songs?

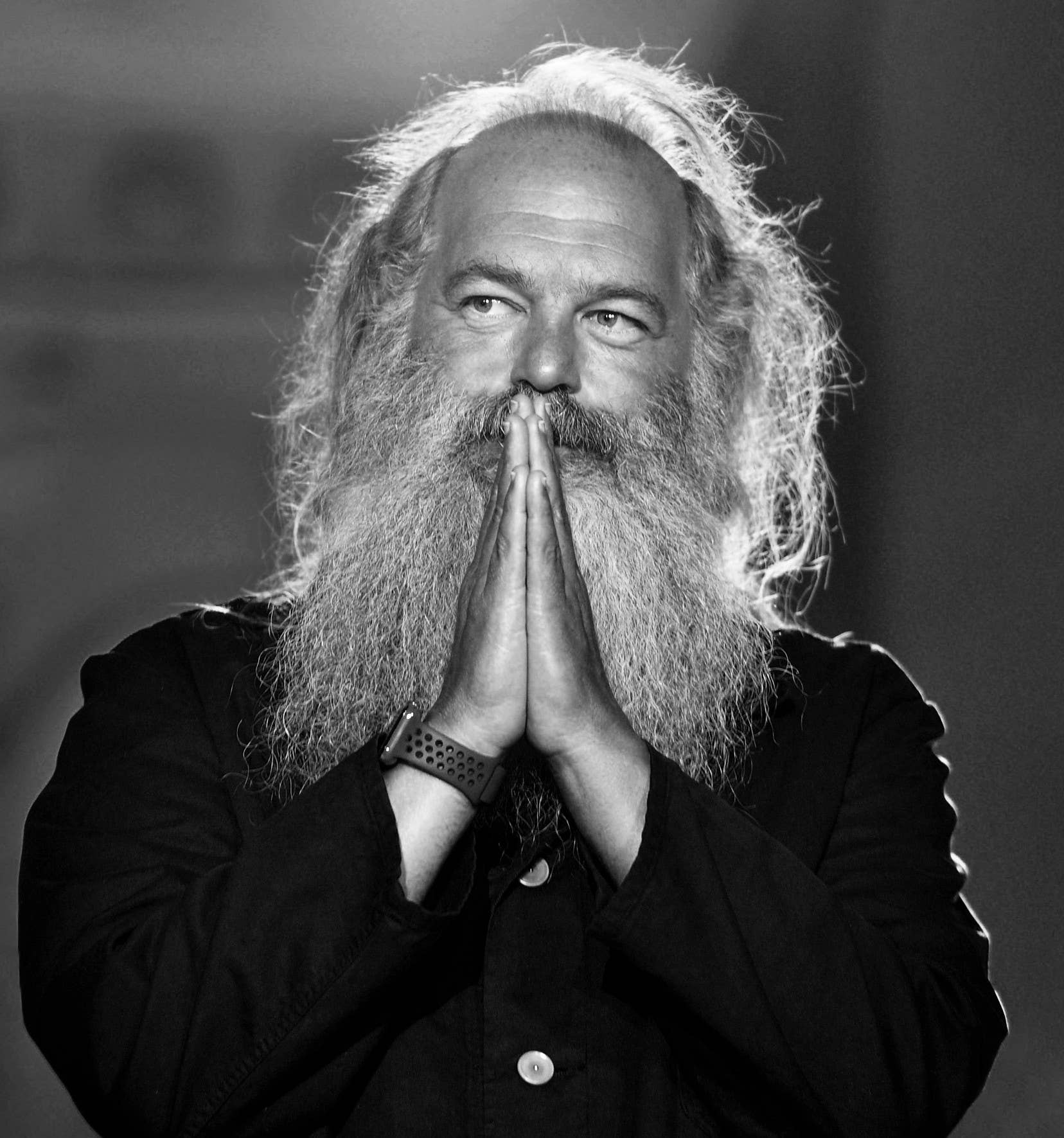

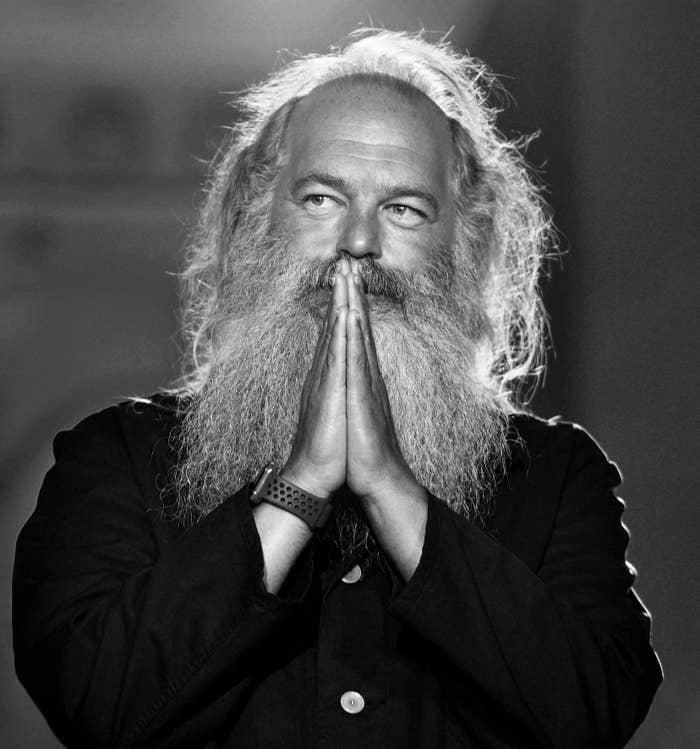

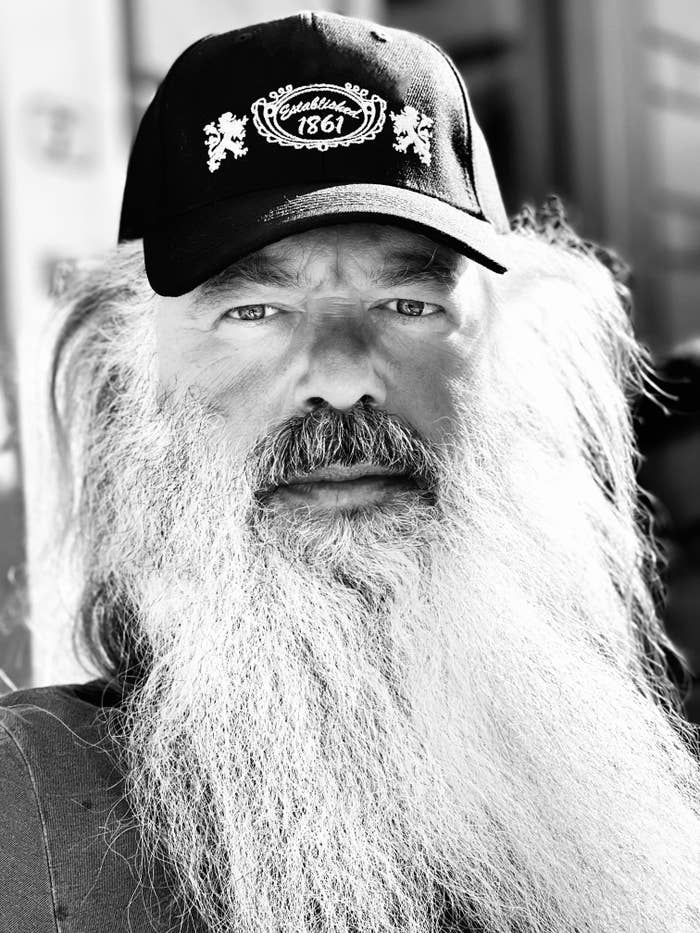

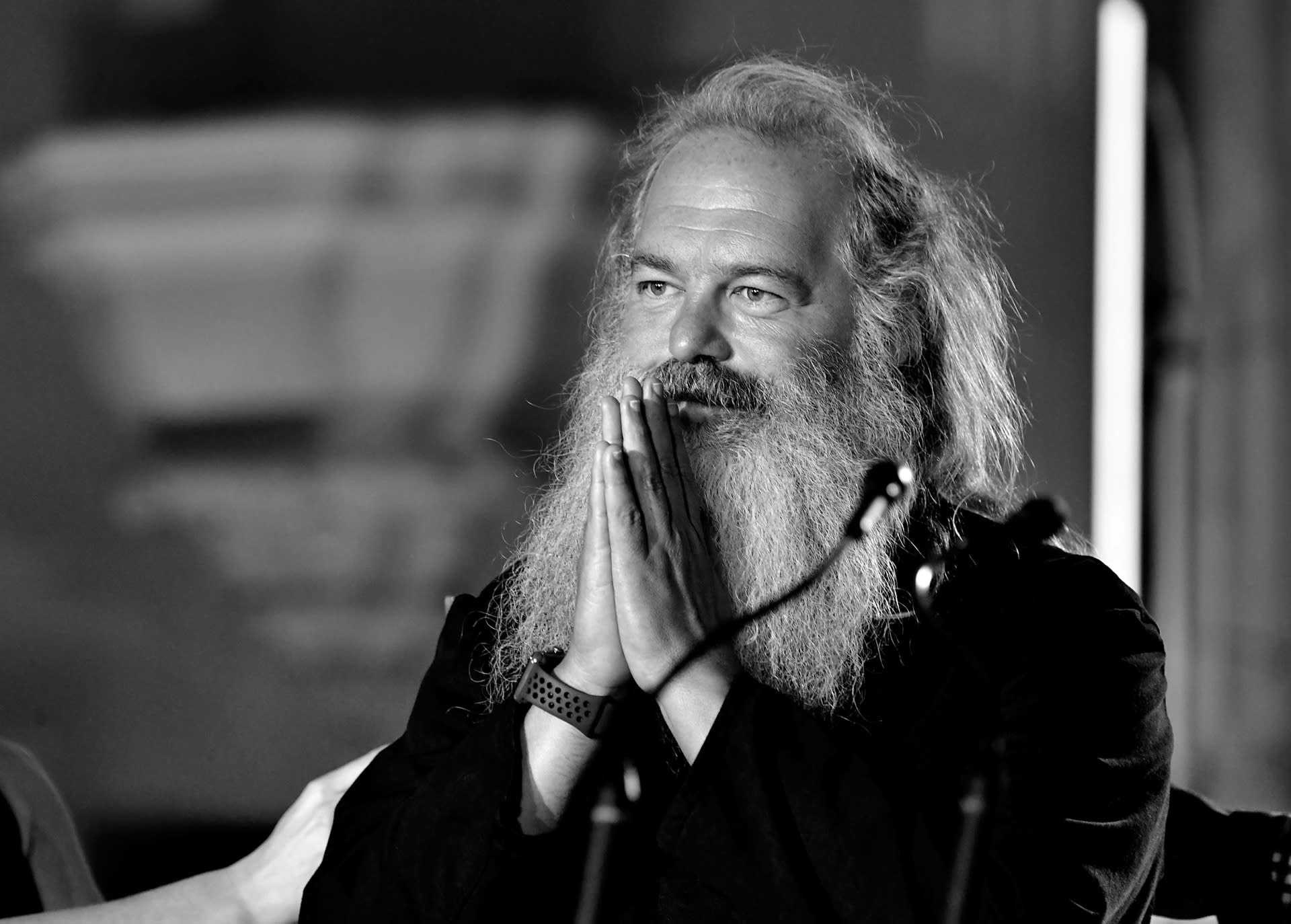

These are the kinds of existential questions about creativity that Rick Rubin is intimately familiar with. For the past four decades, the record producer has been making classic songs and albums with the best musicians in the world, from Run-DMC to Jay-Z to Adele. Some call him a spirit guide. Others refer to him as a guru. But if you ask him, he’s just here to do “whatever’s necessary for the music to be the best it can be.”

Rubin’s mystical approach to music has become the stuff of legend. He likes to walk around barefoot (it helps him stay in tune with the natural vibrations of the earth) and he often lays on his back with his eyes closed while he works. His impossibly large beard has turned completely white, which only adds to his mystique, accentuating the subtle gems of wisdom that invariably roll off his tongue in the studio. Rubin is the first to admit that he isn’t the most technically proficient producer—he says he “barely” plays instruments and rarely touches a soundboard—but he’s an extremely attentive listener who asks simple but thought-provoking questions that have a way of unlocking new creative possibilities for his collaborators.

Whether he’s working with a singer like Johnny Cash, a rapper like Kanye West, or a heavy metal band like Slayer, the 59-year-old producer has a knack for gently guiding his collaborators into groundbreaking territory. Sometimes all it takes is a single conversation with Rubin for an artist to break through years of writer’s block and make the best music of their lives. On many occasions, world-class musicians have left his infamous Shangri-La recording studio in Malibu with songs they didn’t even know they were capable of.

So, how does he do it? What advice does he offer to the artists he works with? What does he know about creativity that the rest of us might not?

Well, for the past eight years, Rick Rubin has been chipping away at a book called The Creative Act: A Way of Being, which contains his core philosophies on creativity. He tells Complex that he started writing the book with a mission “to distill the information of the kind of stuff that happens in the studio, and share it in a way that would be useful to someone else.” He’s never been interested in writing a memoir full of stories about his time with A-list artists, but he was excited by the prospect of writing something that might inspire readers to get up and go make something.

“I didn’t want it to tell any stories about any experiences I had,” he explains. “I wanted it to be more of a philosophical meditation on creativity. And I was hoping for a book that you could pick up anywhere, open to any page, and get information that would be helpful. I was hoping that it would be open-ended and poetic enough that if you were to read it several times, every time you read it, you would get something new.”

What he ended up with, after experimenting with multiple iterations of the book, is a beautiful rumination on the creative process. Guiding readers through “78 areas of thought,” Rubin shares his outlook on creativity, which in turn reflects the way in which he views the world. For example, he suggests that creative ideas don’t simply spring from within the minds of artists. Rather, an artist’s job is to tap into the larger creative energy of the universe and translate it into art that they can share with others.

“We are all translators for messages the universe is broadcasting,” Rubin writes. “The best artists tend to be the ones with the most sensitive antennae to draw in the energy resonating at a particular moment.”

Rubin has spent his entire career avoiding the temptation to overthink and intellectualize his process in the studio (he’s famously guided by feeling over everything) so the exercise of describing slippery, abstract concepts with words was a novel new challenge for him. “When I read the book, I’m surprised by what’s in it, because it’s not front-of-mind,” he reveals. “It’s not easy to grasp. So much of what happens in the studio is not anything that I know. It’s more about intuitive reactions in the moment. So it took years to try to understand what happens in the studio and why some of the decisions that were made were made.”

Still, the book does a remarkable job of explaining these deep, philosophical ideas in a way that’s easy to understand. Rubin says he was inspired by two books that changed his perspective on the world (The Tao Te Ching and Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way) and he hopes The Creative Act is similarly useful to readers who stumble upon it in the decades to come.

In conversation, Rubin can’t help but drop nuggets of wisdom every few minutes, even when he’s not trying to. Attempting to explain how he came up with the chapter titles in the book, he slips into a helpful tangent about collaborations. “Most people in collaborations want their idea to win, but that’s not a good collaboration,” he says. “It doesn’t matter at all. All that matters is that the final result is the best thing it can be. If you have an idea and it leads to the best thing that it can be, that’s great, and if someone else has an idea and it leads to be the best thing it could be, it’s just as good. Only the ego cares about whether it’s your idea or not.”

Rubin, whose accomplishments include everything from co-founding Def Jam Recordings to being named “the most important producer of the last 20 years” by MTV, sat down with Complex to discuss his outlook on creativity, his thoughts on the current state of hip-hop, and the making of The Creative Act: A Way of Being, which you can order now. The interview, lightly edited and condensed for clarity, is below.

What does creativity mean to you?

It’s a generative energy. It’s a thing that we all do, all the time. When we do a good version of what we’re doing, it’s usually a creative choice. It could be anything from making something beautiful, which is obvious, to finding a better route home or solving some little daily problem. Whatever it is, there’s a creative solution to that problem, and the most elegant solutions are the creative ones.

What do people get wrong about creativity? What’s a misconception?

That it’s just fun work. That it’s all fun and that it’s all a party. But it’s not that at all. It’s a real life of dedication. If you do it seriously, it’s a very dedicated life, and it’s unlike other jobs. There are some jobs where you’re done with your day’s work, and then you go back to your family or your hobby or what interests you. But when you decide to live your life as an artist, it’s 24/7 forever. There is no off. The subtitle of my book is A Way of Being because it’s just as much a way of being in the world as it is about the things we make.

The things we make are like a timestamp or a diary entry along this life. But that’s not really what it’s about. It’s really about connecting into how you see the world, and how you see the world that’s different than how someone else sees the world. We all see a different version of the world. We think of it as concrete, but all of it is made up. All of it is our perception of the world. Different people have completely different perceptions, and people from different cultures see it in a completely different way. There’s no right or wrong. Everyone perceives it in the way that they perceive it. And I think the reason we make art is to demonstrate how we see it, and to open up something in someone else that allows them to see something in a way that they hadn’t ever seen it before. It’s exciting.

When you talk about the creative act as “a way of being,” I think of an artist like Tyler, The Creator. His entire life is an act of creativity, whether he’s channeling it through music, film, clothes, or anything else.

Absolutely. He lives life as an artist. He’s fully in. There are some artists who want to come and do the least amount of work, and that’s not the height of what artistry is possible. Tyler’s a great example of the heights of what’s possible if you really live your life as an artist. And he does.

In the book, you write a lot about “the source” of creativity that artists tap into when they make art. Can you explain what the source is?

I don’t really know what it is, but I know there’s something. It could be a universal energy or a universal intelligence. Some people would call it God. Some people would call it nature. It’s whatever organizing principle that allows the whole mechanism to work. And it’s working. Everything you see is part of this thing that all of us get to play in. But if we stop playing in it, this thing keeps going on. And we each get to have a role in this creation’s ability to express itself, if we choose to participate.

“It’s not about knowing. It’s all about feeling and noticing what’s happening in your body. If it’s exciting to you, it’s likely that it’ll be exciting to someone else.”

When artists tap into the source of creativity, they often get caught up in wanting to have control over their own work. But in the book, you write: “Demanding to control a work of art would be just as foolish as demanding that an oak tree grow according to your will.” Why is it important to surrender to the flow of inspiration, instead of trying to control our own art?

Because we’re smaller than the things that we can make. If we’re only making things as good as we are, they’ll be small. But if we can tap into a bigger source of information—a bigger wisdom—then we can hold ourselves and ride it, like we’re riding a wave.

There’s a big flow of creative energy that we can tap into and be a part of, and it’s the reason we make the choices we make. Even when we don’t know it, that’s what we’re doing. But when you know it and can recognize it, you can tune yourself to really be part of it. And it takes away a lot of the anxiety of, “Oh, this is on me.” It’s not really on us. There’s a part of it that’s on us, and that part of it is a full-time, huge, exhausting job. And then there’s something else. There’s something that’s coming from beyond us, and hopefully we can find a way to dance with it and have it pull us through.

I may have an idea of a thing I want to make. And then I start making it, and I realize there’s some other thing that it’s trying to be. This other thing that it’s trying to be is actually better than the thing that I wanted to make. Now, if I’m tightly set on the idea of, “I’m the creator, and I’m making this thing,” I’ll miss this bigger opportunity to make the better thing.

[It’s important to] get the ego out of the way. Obviously ego’s involved in a positive way in that it gets us to do anything. But then, [it’s important] to release it, and allow the universe to take over and let [the art] be all that it can be. Look at the signs around it: “I want it to be blue, but it really wants to be red. It’s turning red. But in my mind, it was blue. But look, I see the red version’s more beautiful than the blue version. But in my mind it was going to be blue.”

Allow our minds to be changed all the time, every step of the way. Like, “I thought it was going to be a hard beat, but it sounds better a capella. I had no idea.” Allow it to go where it wants to go, and try a lot of things. Don’t hold our own ideas too tightly, so that they can find their own voice in the world, which isn’t coming from us. We’re involved, and we’re supporting and nurturing it, but it’s bigger than us. Our version is the small version.

It’s all about getting out of your own way. Do you think artists generally get too caught up with overthinking creative decisions?

Absolutely. Especially in success. Once you’ve been successful, there’s a lot of pressure to continue that, whereas usually when you were doing the thing that made you successful in the first place, nobody was looking and nobody cared. Then when you get successful, there’s all this pressure. It’s like, “Oh, now I’m making something and everybody’s going to see it.” You start treating it differently. It’s important to do anything you can do to get back to that original state where the stakes were low.

Maybe I’m making something and putting it up on SoundCloud. Maybe 20 people hear it. I can do that all day without feeling really stressed out that this is going to screw anything up. It’s like, you have a lot of free throws. But once people are watching, you don’t feel that anymore. And it’s dangerous to feel this weight. I know so many artists who have trouble either repeating great work or putting out things on a regular basis. We see lots of artists who have three, four, five years between projects. And it’s not because it takes that long for it to be good. It’s almost like it takes that long for them to get into the mental state where they feel okay, and aren’t so vulnerable to be able to try it again.

Do you have any tips for creative people who are stuck overthinking everything and want to create more freely?

Yeah. One thing I would suggest is finding a way to make a lot of things and put them out, just to get a cycle going, without even thinking that it’s for anybody or that it’s going to accomplish anything. But every time you put something out, it makes it that much easier to put something else out. So you’re creating a sense of freedom in making things and putting them out.

And if you make something that you’re excited enough to play for your friend who’s got good taste, it’s time to put it out. If you are ready to play it for your friend, that’s the ultimate goal of any of the things we’re making. And I play things for my friend early. As soon as I’m excited, I might play it for my friend, way before it’s really come into all that it could be.

In the book, you point out that an artist’s best work is the work that they’re excited about. When artists get excited by a specific part of the creative process, you suggest that they follow that feeling, almost like it’s a guide. You even give this feeling a name: “the ecstatic.” How would you describe the ecstatic?

The question is: How do you know when something is good? You make a lot of things, so how do you know this one’s good and this one’s not good? And the answer is in this energy of “the ecstatic.” It’s this feeling of… It could make you laugh. It could make you lean forward. It could make you want to listen again. It could make you want to read it again. It could make you want to watch it again. Something that gives you that feeling of: “I can’t really believe what’s happening here. I want to experience this again, or I’m taken out of myself.”

Sometimes I’m listening to music and I forget where I am. It’s a good feeling to get lost in the music. When that happens, it’s a good sign, because if I’m lost in it, and my entire attention is there. I don’t even exist anymore. If it has that power to do that, maybe it’ll have that power to do that to someone else. So you’re following these inner signs.

And it’s different from what you think. What you think is an intellectual process. It’s like, “This makes sense. This is the kind of thing someone else is going to like.” That’s intellectual. This thing that makes me stand up or that makes me lean forward or that makes me hit rewind and play it again, that’s the feeling [of the ecstatic]. And it’s not intellectual. You might not even know why you like it.

It’s not about knowing. It’s all about feeling and noticing what’s happening in your body. If you’re bored in your body, it’s going to be boring to someone else, chances are. And if it’s exciting to you, it’s likely that it’ll be exciting to someone else. You never know, but your best chance is to follow that energy in your body that lights you up. Whatever lights you up is the way to go, even if it seems crazy or wrong or bad, because sometimes things that are bad make you really excited. Sometimes the crummy version is the good one. Sometimes the bad demo is better than the well-produced version. It happens. Sometimes the sketch is better than the oil painting. We don’t know.

Let’s say we create a sketch. It’s really exciting, and then we think, “OK, this is going to make a great oil painting.” And now we spend months working on the painting. Many people find it hard, after putting months into a painting, to look back and say, “You know what? That first five-minute sketch is actually better than the painting. That’s the version we’re putting out.” Wherever the energy lies is the thing to use. There’s no right or wrong. There’s no professional quality version. None of that matters. All that matters is the one that makes you feel it.

Where do you think that feeling comes from? Does it happen when you’re fully aligned with the universe, or what?

I’m not sure. I don’t know if it’s that. I think it might have more to do with a feeling of experiencing something new. I think the unexpected is part of it. Or in some cases it’s the comfort of something that’s done really well. You can hear a new artist that doesn’t sound like anything you’ve ever heard before, and it’s really exciting, and that lights you up. And then you can hear an artist who reminds you of other things you’ve heard before, but you’ve never heard it done this well.

“It doesn’t really matter to me what way I’m participating. All that I care about is that I can do anything to shepherd this thing to be the best thing it can be.”

Some artists can’t help but laugh or shout when they’re struck by a really great idea. Can you think of a time when you were working with an artist and you couldn’t stop laughing because the idea was so good?

It happens all the time. Laughter happens all the time, and then there’s another one that happens a lot. Sometimes multiple musicians will be playing together, and it’s pretty good. Then they’ll keep playing it and playing it, and then all of a sudden, something happens and it changes and it gets really good. Nobody knows what’s different. Five minutes before, it sounded almost identical, but now all of a sudden, it’s the coolest thing you’ve ever heard. When things come into focus in that moment, it’s exciting and a little scary, because there’s this feeling of: “I don’t want it to stop. I don’t know why five minutes ago it seemed the same and it was not good, and now it’s five minutes later, I can’t even tell what changed, and it’s amazing. How can we get through a whole song like this? What is it?” And it’s out of our control. That’s a thrill when it’s happening. It could either be great excitement or a sense of fear of not wanting it to go away because it’s so elusive.

People call you a “record producer” and all these fancy titles, but there are still misconceptions about what you do. At its most core level, when you sit down with an artist and help them create something, what are you there to do? What is your role?

Honestly, whatever’s necessary for the music to be the best it could be. In the early days, it was making beats, and maybe editing vocals or writing vocals. It doesn’t really matter to me what way I’m participating. All that I care about is that I can do anything to shepherd this thing to be the best thing it can be. And that depends a tremendous amount on who the artist is, where they’re at in what they’re doing, what they’re hoping to accomplish, and what they want to make. If they’re hoping to accomplish something that’s not for the highest good, I’ll probably tell them that, too. Like, if they only care about a chart position or something, it’s not so important. You want to make music to change the world. You want to make something that’s going to be somebody’s favorite thing, not to play into games.

Sometimes I’ll just be a sounding board: “Which of these lyrics do you like better?” Or somebody will play me a song, and I’ll share how it makes me feel and any thoughts I have of ways that we can improve it. Sometimes I’ll say, “This is great. Let’s just have this. It already sounds done.” Sometimes I’ll say, “I don’t know if the content is strong enough yet. When you say these words, it makes me feel this. Is that what you’re going for? Is that what you’re hoping for?” And sometimes I’ll say, “Yeah, that’s exactly it.” Sometimes it’s about the feel. Sometimes it’s about the rhythm. It could literally be any aspect.

Sometimes an artist comes to me and they’re like, “I’ve made all these things and I’ve been really successful, but I’m lost. I don’t know what to do next.” And then it’s, like, “Let’s figure it out together. Tell me, what do you like? What do you feel? When was the last time you were really excited by it? What was the first time you were really excited by it?” I just try to understand and help them—just helping artists get out of their own way. Sometimes they’re just in their head too much. Like, if they’re worried, and I hear something and I know it’s good, sometimes just having the confidence that they don’t have for themselves is all they need.

That’s another thing. I’m not saying I like anything if I don’t like it. I’m completely honest. So to have an honest sounding board is helpful, especially for artists who get so successful that it’s hard to get people to be honest, because everybody wants to say everything’s great.

I know you focus on pre-production a lot. Do you ever have conversations with artists before they even start working on an album, and it ends up being more impactful than any hands-on work you could provide in the studio?

Absolutely. I don’t always know about it when it’s happening, but often years later, someone will say to me… “You said this thing, and it completely changed the way I did everything I did. That was the key to everything.” And it’s like, “Really?! That’s amazing.”

None of it is premeditated. I’m present. I really listen to what the artists say, and I share whatever really comes up in me. And it’s real. We’re talking about real stuff. Any criticism is very matter-of-fact. If I say, “I don’t know if this line’s as good as the rest,” that’s not me saying, “Your writing isn’t good enough.” It’s not combative. It’s, “I’m on your team to notice anything that I think could be better. And let’s talk about it.”

I said it once to Neil Young. I read his lyrics for a song, and I said, “I don’t know. I don’t think this line’s as good as the rest. Are you okay with it?” And he’s like, “You know, I always questioned that line. Now that you pointed it out, I have to fix it. Eventually, I just got lazy, and thought maybe nobody would notice.”

I had the same conversation once with Tom Petty, where there was a line in the chorus of a song, and I thought it was lazy. There’s only four lines in the chorus, and this one was a throwaway line. It’s like, “You have so little real estate to say what you want to say, and this feels like a throwaway line.” He’s like, “That’s the best line in the whole song. That’s what the song is.”

You were around for the early days of hip-hop’s evolution, and you watched it grow from a niche subculture into the most dominant genre in the world. From your own firsthand perspective, why do you think that happened? What makes hip-hop so special and why did it connect with so many people?

I don’t know if I can answer that. My first thought in reaction to your question would be: I think it’s that it keeps renewing itself. It keeps reinventing itself. It’s an open-ended enough genre of music to where there can always be a new take on it. It could be a new rhythmic take. It could be a new lyrical take. It could be a new style.

In the early days, when I was first involved in it, the idea that it would become what it became was not a possibility. There was no chance. Nobody who was making hip-hop music thought, “This is going to be the biggest thing in the world. It was completely underground, fringe music.” There was a tiny amount of people that really liked it. And most people didn’t even think it was music. It was that foreign. It was that outside of everything else that was going on.

But when hip-hop really broke big, then something shifted and more people were getting involved, because it was big instead of because it was the thing they loved. And I stopped making hip-hop records at that time because it felt like it changed away from this pure, creative endeavor into something else.

Then, over time, it reinvented itself again. I had stopped listening to hip-hop for a little while. A couple of years, maybe. And then I remember the first time I heard Eazy-E. And then NWA. It was like, “Oh, this is interesting. We haven’t heard this before.” It made it new again. Then I remember when I first heard Wu-Tang; that made it new again. When I first heard Kanye, that made it new again. So there’ve been these waves where it gets reinvented. And just when I think I’m not so interested anymore, something happens to get me interested again.

Ice-T made this movie called Something from Nothing: The Art of Rap, and I remember seeing it in a movie theater. It has all of the great MCs rapping a capella and talking about their writing process. It made me fall so back in love with hip-hop. It was so beautiful and so great.

With hip-hop, the music was as much of a driving force for me as the lyrics. I like lyrics and I like the phrasing and I like the musicality of the phrasing, but the music is what drives it for me. The beats are what drives it for me, and the energy of the rhythm is what drives it for me. So to see this movie where it wasn’t about that—it was only about the words, really—it was just like, “Oh yeah, this is why it’s so great. Of course.” That was a real eye-opening experience.

What do you think about what’s happening in hip-hop right now? What excites you about rap in its current moment?

Artists seem open to trying new things. It feels like a very open time, a very free time. And I love that about it. I love the potential of hearing something I haven’t heard before. It’s very exciting. I heard something recently. I can’t think of what it is, but I heard something recently that just kept surprising me. Even in the course of one track, it just kept surprising me. It’s like, “Oh, this is really good.” It was a great feeling.

It feels like a lot of new hip-hop artists are willing to experiment and be weird right now. And they’re being rewarded for getting weird, too, which is cool.

Absolutely. I like it.

Did you cut anything from the book that you think would be useful for our readers to hear?

I’ll tell you something that happened since writing the book that was interesting. If the book wasn’t already done, it might have been in the book. I was working with an artist who played me a song with lyrics that didn’t pull me in. It didn’t sound like what she was singing about was important to her based on the lyrics. It didn’t seem like there was a reason for the song.

I said, “Is the song about something real? Are you really connected to what you’re saying?” And she’s like, “Yeah, it’s a really heavy song. The story of what happened in the song is very heavy.” And I said, “OK, for whatever reason, I’m not getting that from the song.” I’d never tried this before, but it was an interesting experiment. I said, “Tonight, instead of trying to revise lyrics of the song, write an essay. Write five or ten pages, or however long it has to be, of the story. Write out the story with all of the emotion of it. Really put it all into the essay. Really squeeze out all that’s in that story.” She did that, and then I said, “OK, now let’s look through the essay and underline the most charged parts of the story from a content perspective, or any lines that were good.”

Usually, when we’re working on lyrics and the structure of the song’s already written, it’s a little bit like a crossword puzzle. We’re looking for words that have this many syllables and fit into this space and have the accent in this spot, because that’s where the melody accents, and the word has to make sense. It’s like filling in a puzzle. It’s very limited in the songwriting structure, because you have a very specific place to fit an idea. You have limited real estate to fit the idea in. If you have a song with four lines in the verse, and there’s three verses, you have 12 sentences to tell the whole story of the song, plus whatever the chorus is. And if you’re focused on just filling in these 12 sentences, you might miss where the energy is in the story, because you’re looking too small. You’re only looking, like, “Well, I only have five words that can fit here. What can I get in five words?” You’re not thinking about the big story. You’re just thinking about what the best solution to the puzzle is.

But by writing the essay, we see where the meat of the story is. We can see the ideas that we’ve got to add to the song, or the words that need to make it in the song. It refocused the lyrics to be about the content of the lyrics instead of the structure of the song, which is what most songwriters are focused on. It seemed like a big idea to break out of writing for the structure of the song. If that had happened before the book was finished, the idea would’ve been in the book.

What’s the meaning of life?

To have fun. We’re here to enjoy ourselves. We’re here to have fun and we’re here to self-express. We’re here to say, “This is me.”