“I’ve seen a lot of violent incidents.”

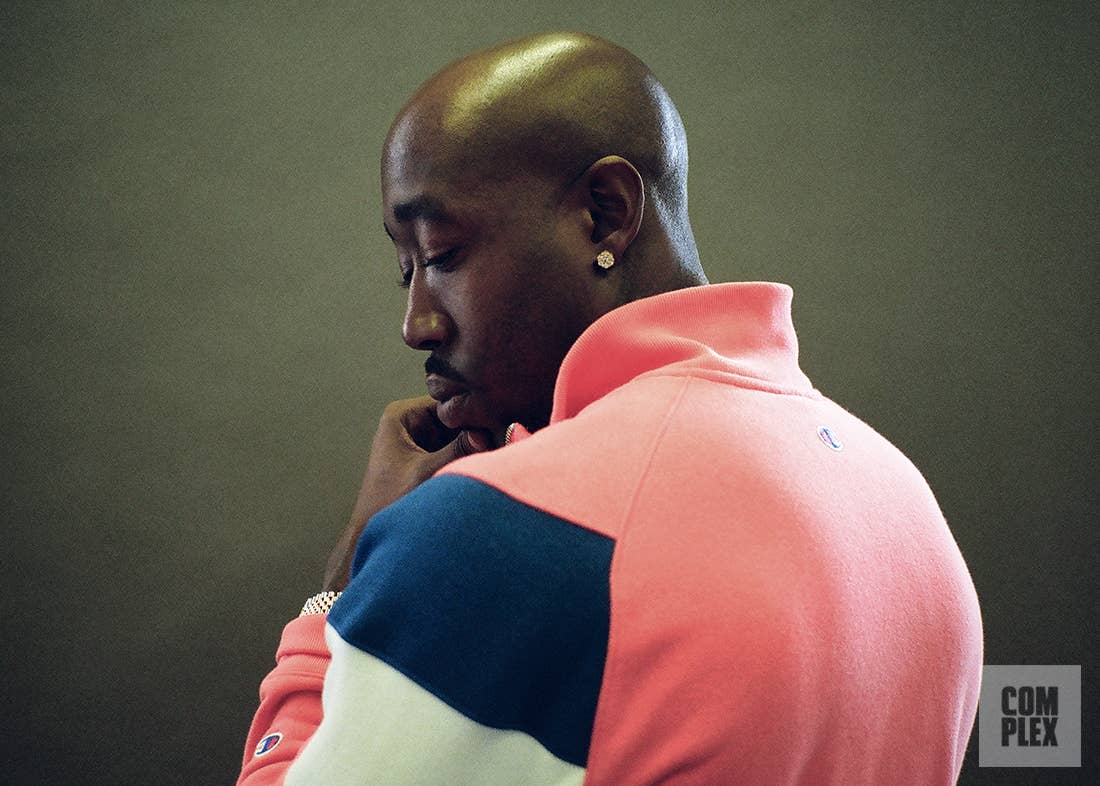

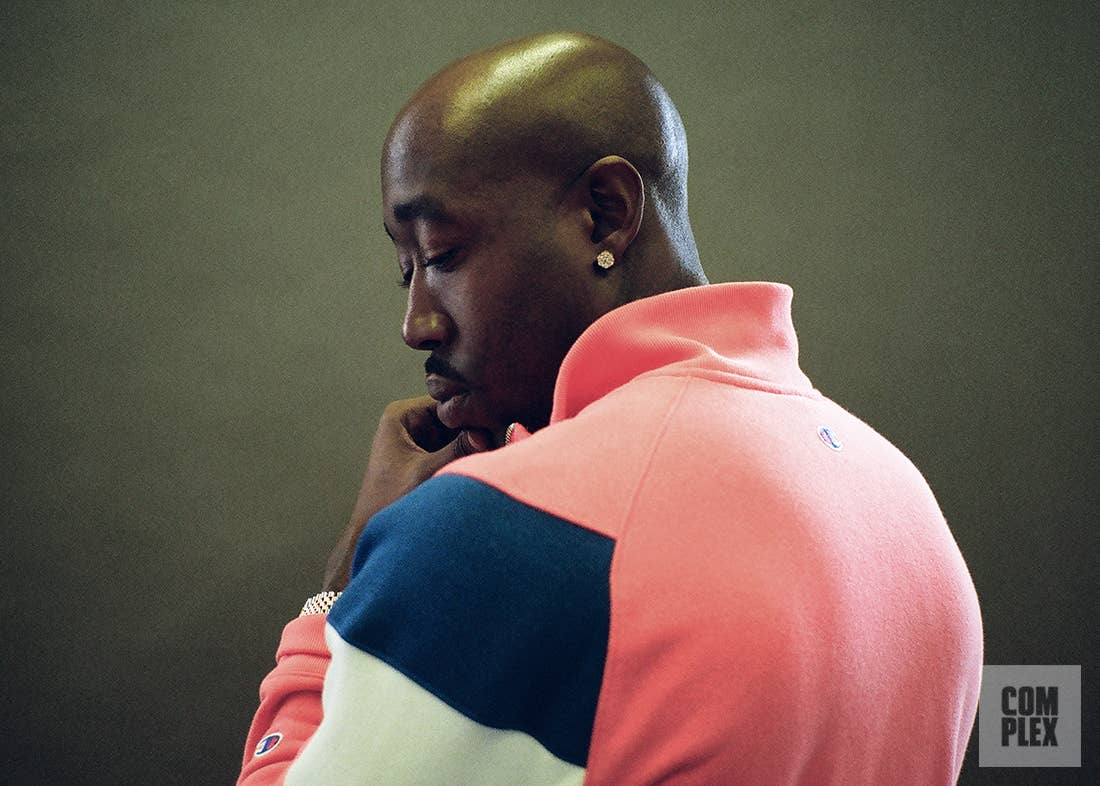

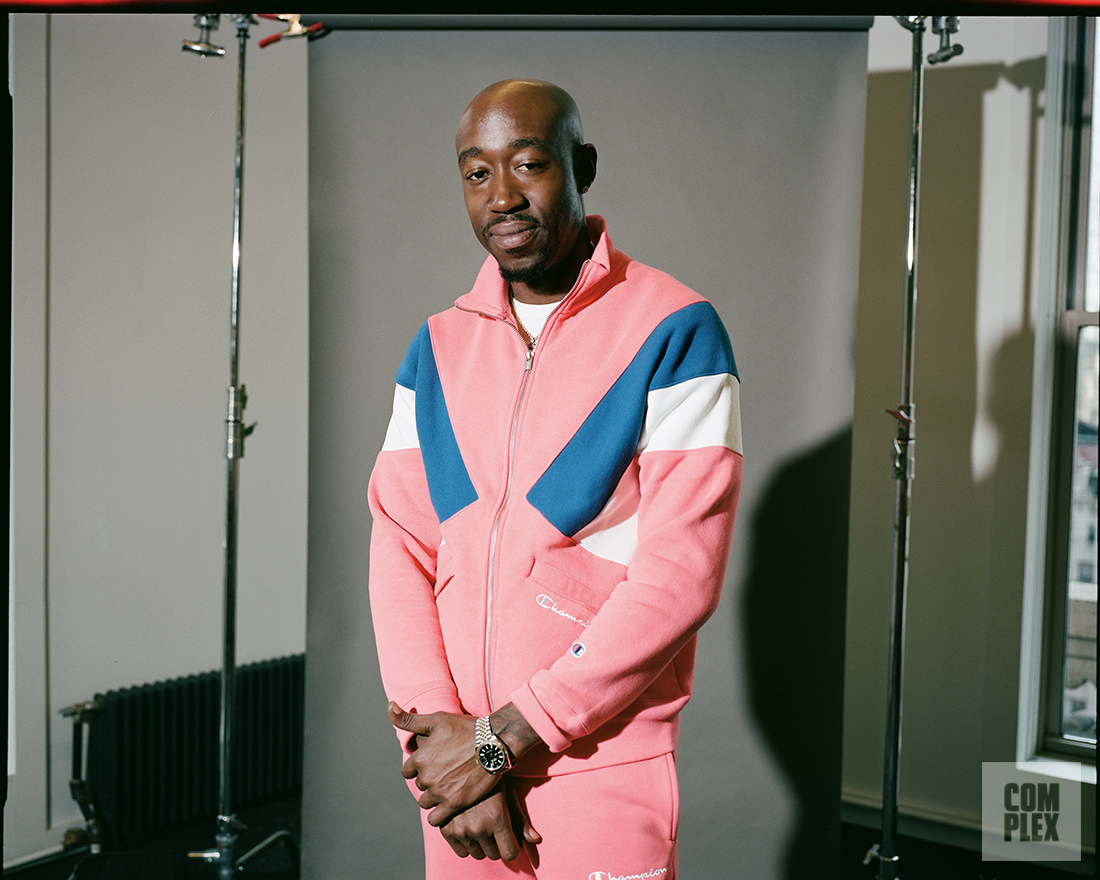

Freddie Gibbs is reflecting on the imagery in his song “Bandana,” which doubles as the title of his new album with Madlib: a filthy, blood-stained bandana.

My brand new hammer

Once I used it, it was dirty like the blood stains on my bandana

“You don’t never get away from that,” Gibbs adds. The 36-year-old rapper, whose catalog of songs about his eventful California-via-Indiana life has brought him critical love and a cult fanbase, is seated in a cavernous New York City studio on an early spring afternoon. “You don’t ever forget that. You don’t ever lay that down. You think about a lot of that when you sleep, when you wake up. It’s damn near like having PTSD. A lot of those images are ingrained and burned in my mind forever. So getting it out on raps is therapeutic.”

The latest batch of those raps make up Bandana, Gibbs’ second full-length collaboration with Madlib. Their last project, 2014’s Piñata, was critically beloved for its mix of Madlib’s ominous and detail-laden beats with Gibbs’ artfully delivered tales of street life. When the pairing was first announced in 2011, it struck some as strange. The Cali-born producer, best known for his arty music with the likes of MF DOOM and Dilla, wasn’t the most obvious match for a rapper who was “wearing a Bo Jackson jersey and a durag, two pistols in his pocket” when he met his manager Ben “Lambo” Lambert. But Gibbs now sees the producer as an older brother figure, and he says rapping on Madlib’s beats is a puzzle he’s eager to solve.

“I was up for the challenge,” Gibbs explains. “I want him to take me to different levels of making music that I never knew I could unlock. It’s a certain way you gotta attack these beats. If anybody could rap ’em, then everybody would be doing it.”

On Piñata, the duo worked separately, as Gibbs selected production from beat CDs. The follow-up was more of a collaborative project, and they each made an effort to get in the studio together. “This project took a while to complete, so there were times when it was good to get together and discuss things like which beats to use, which features we wanted to get, and go over mixes and edits,” Madlib notes. It was a pairing that occasionally led to some surprising moments. “Me and Madlib was bumpin’ Lil Baby, straight up,” Gibbs remembers.

Bandana’s lyrics, a mix of dark sentiments and memories, nod to hip-hop’s storied Nation of Islam and Gods and Earths influences, while the album’s sharp observations on current events mostly come from Gibbs’ time behind bars in 2016. In June of that year, he was arrested in France, accused of spiking a 17-year-old girl’s drink and raping her the prior August in Austria. Immediately before the arrest, Gibbs received a batch of Madlib beats.

“I was listening to Madlib’s beats when the fucking police arrested me,” Gibbs remembers. He was facing up to a decade in jail if convicted, but a Vienna regional court ruled that there was not enough evidence that Gibbs had sex with the alleged victim, and he was found not guilty. It was between the arrest in June and his acquittal in September that Gibbs penned a good chunk of Bandana, which is due out this summer. “It was so easy to write the raps when I was in jail because I had the beats in my head already,” he says. “I didn’t have nothing in there but God and my memories. All I could do was just remember beats.”

“I was listening to Madlib’s beats when the f*cking police arrested me.”

Being in an Austrian jail facing a precarious future is far from the only uncertain chapter in Freddie Gibbs’ past. Before he even started in music, the rapper faced tough odds. At Ball State, he tried his hand at a football career (recalling the play that ended his playing days: “This motherfucker hit me so hard he flipped me in the air, like, three full times, and when I was in the air flipping, I was like, ‘Yeah, football career shit is over’”). After that, when Gibbs was 19, a judge not-so-gently suggested he join the Army to avoid theft and gun charges. That didn’t last long, either. He would be kicked out after eight months for smoking weed, though he would later name his first mixtape series Full Metal Jackit in homage to his time in the service.

With college football and the Army out of the picture, Gibbs did the next-best thing: He found a new career at the mall. While hanging out at Gary’s Village Shopping Center, he met the producer Finger Roll, who was the city’s most successful producer at the time. “He was the only guy that had a studio,” Gibbs recalls. That meeting led to the aspiring rapper’s first attempts at recording, before he joined Finger Roll’s No Tamin Entertainment crew and released his first solo mixtape via their auspices in 2004.

In 2005, Ben Lambert would hear one of Gibbs’ early efforts while he was studying at U.C. Berkeley and interning at Interscope. He was told by his boss at the label that if he could find a rapper to sign, the internship could turn into a full-time job. Lambert decided to search outside of the coasts, and one day, while looking on the now-defunct hip-hop website Southwest Connection (which, despite its name, covered no shortage of Midwestern artists), he heard a guy rapping on an Allen Iverson beat.

Lambert heard something special in Gibbs’ rough demo, which included a Chingy diss. (“He was wack as fuck, and I was jealous,” Gibbs now laughingly admits.) That interest led to Gibbs signing a deal with Interscope, and leaving Indiana for Los Angeles. He was dropped from the label before getting a chance to release an album, but the deal gave Gibbs what he needed: a new home on the West Coast, a stash of songs with top-notch producers like Just Blaze, and a career-long partner in Lambert.

Lambert is now Gibbs’ manager. It was Lambo, a former Stones Throw employee, who was responsible for connecting Gibbs and Madlib, via his relationship with the producer’s business partner and former Stones Throw GM Eothen “Egon” Alapatt.

Lambo and Gibbs have matured over the course of their partnership. They’ve been there for each other as they each became dads, navigated serious relationships (Lambert married Priya Rideau in 2015, and Gibbs was at one point engaged to Insecure actress Erica Dickerson, daughter of football Hall of Famer Eric Dickerson, though the two have since split), and made their way through hard times and tragedies.

“I think a lot of guys are INFLUENCED BY ‘Piñata.’ I fathered a lot of styles off that album.”

The late Josh “The Goon” Fadem was Gibbs’ engineer and occasional producer over the years, but he also represented a lot more than that for the rapper. After the Interscope deal fell through and Gibbs abandoned L.A. for Atlanta, it was Lambo and Fadem who got him out of trouble and convinced him to come back. Fadem even let him sleep on his couch, and engineered almost all of his work. “Josh the Goon got a n***a back to flowin’,” Gibbs raps on his new song “Situations.”

Fadem also contributed to Freddie’s hysterical, meme-heavy Instagram account (Gibbs says his daily Instagram Story posts are followed closely by everyone from Kevin Durant to Snoop Dogg). “Every day, me and him would be looking at filth on the internet,” he remembers of Fadem. “And it would be so fuckin’ funny, man.”

When Fadem died of an enlarged heart in 2017, the news came as a major blow to both Gibbs and Lambert. “We did this for you Josh,” Lambert wrote on Instagram just last month, posting a picture of the trio. “We love you and we miss you every day.”

Gibbs dealt with Fadem’s death by putting together a more public version of their private time laughing at ridiculous internet jokes together. “One of the ways for me to deal with Josh passing was posting memes,” Gibbs reveals, breaking down in tears at the memory. “I really miss that guy, man. And every time I post one of those, it just reminds me of me and him laughing. I miss that. Every day I miss that. Laugh to stop the crying.

“I wouldn’t be where I'm at without those guys,” Gibbs continues, referring to Fadem and Lambert. “I wouldn’t have my kids without those guys. It hurts me every day. I’m at such a great place in my life, and I can’t share it with all the people who helped me get there.”

Freddie Gibbs’ “great place” is not metaphorical; for the first time since being dropped from Interscope, he is in business with a major record company. Tunji Balogun, whose relationship with Gibbs and Lambert goes back a decade, is the executive vice president of A&R at RCA Records and a co-founder of the label Keep Cool (a joint venture with RCA). Bandana will be released on Keep Cool/RCA.

It’s a fitting home for Gibbs. He’s back in the major-label system, with the resources to get his music to the masses, but this time with a friend at the helm. He feels that the mainstream music industry has consistently stolen his moves since he went independent. There’s been the voluntary stuff (he lists one or two maybe-he’s-joking-maybe-he’s-not examples of ghostwriting during our afternoon together), but he also points out that time in 2010 when he released his Str8 Killa No Filla mixtape for free, followed by a shortened EP version up for sale: a model that became common in the years afterwards. Gibbs then released a shorter-than-normal album in 2017 with the eight-track You Only Live 2wice, only to see music’s biggest stars run with that idea.

Now he’s anxious to get on the bigger stage that his new deal provides, and he’s confident that Bandana can stand up to the increased scrutiny. Madlib agrees: “I knew the album was going to be good, and straight to the point. I trust my collaborators, and they trust me. When we’re creating, we’re not thinking of anything except making the best music possible.”

Bandana meets the producer’s lofty description. Appropriately enough, given that it was written largely behind bars, it’s often reflective, looking back at Gibbs’ difficult past and the scars it left behind. “Every time I sleep, dead faces, they occupy my brain,” he says on “Fake Names.” On other songs, Gangsta Gibbs turns political, comparing the Trump era to the crack-besotted 1980s (“We got a reality star in the goddamn office, quite like the Reagan days,” he spits disgustedly on “Palmolive.”)

Musically, the album hews a little closer to soul music than Piñata’s jazz-based sound. And a number of the songs feature beat switches. “That was on me,” Gibbs admits. “I was like, ‘Fuck it, let’s make two beats on a lot of the songs.’ When you can rap on one beat and keep rapping seamlessly when the beat change, I feel like that’s a great technical skill. Not many people can do that. I want [Madlib] to challenge me as an MC and take me to different levels of making music that I never knew I could unlock.”

“There’s definitely not an album like this,” he continues, summing up his thoughts on Bandana. “I think a lot of guys are influenced by Piñata. I fathered a lot of styles off that album. And I’m about to have some kids when this album comes out.”

The album, born in a crucible of time spent in jail and a friend dying, nearly didn’t come out at all. Making it, Gibbs explains, was a process of “trying to find myself again.”

“During the jail shit, it was a lot of praying and reading and soul searching going on during that time when I was making these records,” he recalls. “I didn’t even know if I wanted to rap again after I dealt with that situation. I thought that I was going to just fade and just chill, and probably do something else.” But, Gibbs concludes, “I love this, and it loves me. So I can’t never give it up.”