On an October afternoon, Steve Wilkos waited backstage as his hype man, aptly named JHype, attempted to tame the live studio audience. There was a series of reactions The Steve Wilkos Show crowd needed to practice, but it was too riled up for even cued applause.

After a warning about how the guests don’t get paid—and therefore don’t deserve any “nonsense”—JHype gave the audience its most important prompt: “When Steve comes out, I need you to yell, ‘Steve!’”

Fifteen minutes later, Wilkos’ 6’3” frame finally emerged on stage. “Steve!” the audience dutifully chanted. “I love you, Steve!” an older woman screamed. Wilkos nodded curtly, then took a sip of something hot. Between his too-big, icy blue eyes and imposing bald head, he looked like a gritty Mr. Clean.

The first segment of the day was a woman named Deseray, who wanted to do a paternity test on her youngest son. The hopeful father, O.J., was pale and thin, soft-spoken and clearly unsure what the results might be. After a video presentation of their backstory, Deseray joined O.J. nervously on stage. Wilkos’ wife and the show’s executive producer, Rachelle, darted out to hand Wilkos an envelope.

“You are,” he announced, pausing for painful, dramatic effect, “not the father.”

“You THOT!” one audience member erupted. “Deseray, you are a goddamn THOT!”

O.J. shrank two sizes in defeat, and Deseray grabbed his hand. Security moved to escort the extremely aggravated man out of the audience, as he attempted to repeat the acronym for “that hoe over there” as many times as possible before ejected from the studio entirely. “You a dirty-ass THOT, Deseray,” his distant voice continued screaming. “THOT!!!”

“People say, ‘That’s trash, and this, and that,’” Wilkos says, before pivoting and taking aim at those detractors. “Well, it’s what people want. It’s what they watch. [Daytime] keeps trying to reinvent the wheel and failing.”

In the 10 seasons since Wilkos emerged from Jerry Springer’s security staff to host his own program, The Steve Wilkos Show has earned an average of 2.1 million daily viewers, and is one of only three syndicated talk shows (Rachael Ray, The Real) that have delivered year-to-year growth. At 52, Wilkos has built a small empire out of being a straight-talking ex-cop, and his influence extends beyond entertainment value. There’s a loyal audience at home who flips him on most afternoons, and a portion of that viewership who trusts Wilkos enough to believe his tough love is the only solution to their problems.

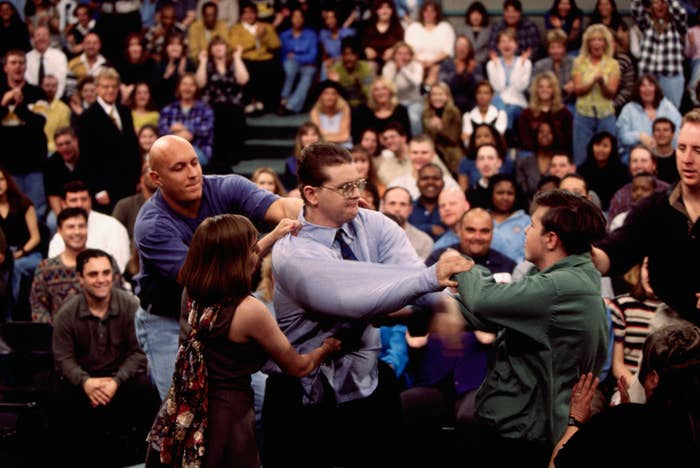

Wilkos’ show, and his notoriety on The Springer Show, has always been about helping people. The “thot” outburst distracted from the vulnerability of Deseray and O.J., though there is still a notable contrast at play. In Springer’s hands, the couple would have been coaxed into a fight. O.J. would have had to be restrained by a team of bodyguards as Deseray hopped on Singer’s signature stripper pole for a bit of aggressive disrobing. But Wilkos isn’t about theatrical scandal. Deseray and O.J. sought him out for closure, and despite the interruption, that’s exactly what they seemingly got. Wilkos has built something far more grounded than his predecessors—Springer himself would be the first to tell you The Wilkos Show isn’t The Springer Show.

“My show is mostly comedy, you know, we do a circus,” Springer says. “Steve became more serious. He was the tough guy who would be in your face… The viewers loved him.”

After graduating from Lane Technical High School in Chicago in 1982, Wilkos joined the Marines, but not even that could prepare him for the next chapter his life as a Chicago police officer. On his very first call during his first day on the job, he and his partner were sent into an abandoned building, where a domestic abuse suspect had fled to from the scene of the crime. Wilkos yelled “freeze” with his gun drawn, and soon had the perp in custody. A few hours later, he and his partner were sent to interview the victim.

It’s been nearly two decades since Wilkos was even on the force, but this is a story he will never forget. The suspect asked his girlfriend to get off the phone. She refused, and he proceeded to boil a pot of oil and dump it over her head. The woman Wilkos saw in the hospital that day no longer looked human. Her hair, lips, eyelids, and most of the other defining elements of her face had been burned off.

“Back then I had a dog. I used to come home to that dog and hug it, man,” he explains, arms up, miming a bear hug with his eyes closed. “That dog probably thought I was trying to kill it because I’d squeeze him so hard, but I needed an escape.”

In 1994, Wilkos was patrolling the streets of Chicago when a friend from the force, Mike McDermott, asked if he was interested in a gig. The Jerry Springer Show was in the process of putting Springer’s brand of controversy on steroids, so they needed the extra manpower. Wilkos’s first shift was part of a series of episodes centered around the KKK, meaning producers were genuinely concerned about the potential for a riot. It was a big job, though subduing volatile racists was hardly the most challenging thing Wilkos has ever had to deal with. His blistering, no-nonsense attitude mixed with paternal compassion immediately drew viewers to him, even as he was in the background on Springer.

“Jerry had one role, which was to be Uncle Jerry, and make jokes as the craziness went on around him,” Rachelle explained. “Steve was there to step in when things really got out of control, and I think that’s what they liked. He was the law and order.”

Producers took notice of Wilkos’ traction with the crowd, and started featuring him more prominently, including individual segments titled “Steve To The Rescue,” where he would travel to help people in their homes. It was a bit unfocused—one time he showed up mostly to help a single mom cook—but it defined his role as daytime television’s problem solver.

When Springer was cast on Dancing with the Stars in 2006, it only made sense for Wilkos to fill in as host. NBC assumed Springer would be voted off right away, but he ended up sticking around for seven episodes. With an average of six shows filmed per week, Wilkos had over 30 episodes to cover, and he made enough of an impression that Springer recruited him to fill in every Monday.

“Oprah begat Dr. Phil, so it was time for me to beget someone,” Springer said with a smirk in his voice. “Steve was the obvious choice.”

On the show, Wilkos is a constant witness to unspeakable horrors. The segments range widely in content, but the sexual abuse of children is a consistent thread: examples include such classic titles as “My 4-Year-Old Sister Said You Molested Her,” “I’m Having Nightmares, Did My Dad Molest Me?,”“I Would Never Rape My Own Daughter,” or the more recent addition, “Did You Molest Our Son While I Was in Jail?” Often, Wilkos’ own family appears as a character in the show and he often evokes the Elliot Stabler Law & Order: SVU hypothetical—think I’m angry now? You don’t even want to know what I would do if someone ever touched my kids!—but it’s not an act.

The concept for the show was simply, “A cop who helps people,” but it would take him a full season to realize that he could fulfill that premise by just being himself. The show in its modern iteration is defined by Wilkos’s unflinching aggression, though in the 10 seasons since the premiere, it’s become much more nuanced. There’s a refined tough love where lots of screaming once was. “I had no levels, I had no empathy. It was just, ‘YELL, YELL, YELL, YELL, YELL, YELL!” Wilkos explained, literally yelling the word “yell” six times in a row. He blames, in part, the work of the first executive producer, and says everything changed the second his wife came on board.

Wilkos met Rachelle in 1995 when she was a producer on Springer. The two started dating a few years later, and were married by 2005. At first glance, Rachelle seems like a happy anecdote to Wilkos’ showbiz fairytale, but in many ways, she’s the reason it all began.

Her influence was especially clear in the fourth segment of the taping I was present for, which centered around a brother and sister who had repeatedly slept together. Wilkos emerged in the wings giggling—even he has fits with immaturity—and ran his hand in front of his face to gain composure. Before he could crack, Rachelle speed-walked over, and tugged at the bottom of his shirt. “OK, I’m trying,” Wilkos said, shaking his head back to seriousness.

Rachelle cocked her head, and returned to her podium on the side of the stage. Wilkos began his intro with the proper dose of incest-adjacent intensity.

“I knew he had to get the giggles out for that,” she said over a playful eye roll in her office after filming. “I was like, ‘OK, this is serious. This is serious to these people, and it’s really impacting their life and their marriages.’”

Wilkos has a sense of humor, but the balance of the show depends on achieving a level of seriousness. Many of those 100s of calls a day are from people who truly need help. Various bureaucratic systems have failed them, and they’re paralyzed by their reality, whatever it may be. Sometimes that means getting to the truth of a child sex abuse scandal, other times it’s a matter of forgiveness. There’s a strict system of psychological aftercare offered, and occasionally failed lie detector tests push families to further pursue legal avenues. Still, all Wilkos promises is emotional justice, and most of the time, that’s more than enough to leave guests thankful that they came. What happens on stage is all about a fresh perspective working through the issue, laying out the facts, and offering the tough love solutions he’s known for.

McDermott, who is now The Steve Wilkos Show’s head of security in addition to working as a full-time Chicago cop, says the show is simply showing an enhanced version of who Wilkos was on the force.

“This is just completely Steve. What you’re seeing is actually a police officer at work,” he said. “It works, because there’s no second guessing what he feels about you, and it’s very easy to be around someone like that. It’s, ‘Here’s the truth, and here’s how we’ll deal with it.’”

Of course, there’s no such thing as simply being a police officer in 2016. The advent of increasingly visible instances of police brutality and the Black Lives Matter movement mean the job is fraught with the political. Somehow, being “pro- or anti-cop” is a thing.

Wilkos has feelings about this. During our time together, he shares a variety of dad-like opinions—dad-like in that they are well-intended but woefully outdated. When he starts up about bathroom rights (“A man can go pee in a woman’s bathroom if he identifies as a female person? C’mon, man”), NBC’s publicist visibly cringes, and I try to shift focus back to the show. He continues anyway, finishing out each controversial idea—the need for stop-and-frisk, for example—with only a half look in her direction, before launching into his thoughts on “everything going on with cops right now.”

After an extended bit about New York City mayor Bill deBlasio’s ineptitude, Wilkos explains that he believes a lack of proper training is to blame. It’s something he saw back when he was in the police academy. He recalled one test requiring prospective officers to climb over a six-foot wall. Coming from the marines, he was practically able to jump over it. A lot of people in his class could barely pull themselves up.

“How the fuck did they get their uniform?” Wilkos grumbles. “But that’s that. They just force them through so they pass.”

As he sees it, that low bar and the resulting lack of preparedness is the motivating factor in many high-profile police shootings. “Most policemen don’t want to come in to shoot people or beat people up,” he says matter-of-factly. “Most policemen want to go through their shift with no incidents. They don’t want to fight, they don’t want to shoot anyone. They want to do their jobs and go home. They’re like everybody else. They’ve got families. They’ve got kids. They just want to do their job, make a buck, and go home.”

Wilkos’ perspective is a strangely startling reminder of the “good” cops—people who are just hoping to do their jobs and emerge from the onslaught of awful with their psyche intact. His presence as an entertainer, inextricably linked to his identity as a cop, is a reminder of what it means to be a good police officer.

“Of course, there are rotten cops!” Wilkos bellows when asked. “There are rotten talk show hosts, rotten doctors, rotten dentists, lawyers. There’s rot in every profession. The police department though, it’s life and death, so it’s highlighted so much more. The problem is that we all focus on those few incidents of bad shootings.”

Wilkos attempts to exist outside of that controversial space. In part, he is removed from the fray as a virtue of his aforementioned benevolent, dad-like ignorance. More than that, he’s a separate entity as both a talk show host and a good guy doing his best. Wilkos might not be changing the world by answering questions like “Did You Allow Men to Molest Your Daughter for Drug Money?” or “Is He My Father and Did He Try to Sell Me for Drugs?” on daytime television, but he is reminding a small yet significant audience that helping people is what being a cop should be about. And whether they come for the salaciousness or a genuine desire for healing, that’s a form of closure everyone in this country could use right now.