No matter what people in Cleveland or Memphis might tell you, there’s no easy answer to the question of where rock began. Same with the blues, which has its Chicago and Memphis adherents. But not so with hip-hop, where there is no discussion needed—New York is where it all began, with not so much as a runner-up. But just as NYC is the indisputable cradle of the music that defines pop culture in the 21st century, it’s equally undeniable that the mecca is no longer the center of influence and conversation, ceding its place as the zeitgeist moved south, notably to Atlanta.

Theories abounded for New York’s waning relevance, among them changing tastes, an internet-driven leveling of the field, too many New York beefs, and Gotham’s own stubborn musical conservatism. In a what-have-you-done-for-me-lately world, the capital was in danger of becoming a shrine. For the better part of a decade, blogs asked, “What happened?” and wondered aloud if and when New York would make a “comeback.”

for the better part of a decade, blogs asked, 'what happened?' and wondered aloud if and when new york would make a 'comeback.'

Wonder no more, because 2016—a shitty year in many ways—has proven to be a promising time for New York hip-hop. Faces that had been around for a minute made strides by channeling classic sounds (Dave East, Flatbush Zombies, Young M.A.) and newcomers (Desiigner, A Boogie Wit Da Hoodie, Curly Savv & Dah Dah) burst onto the scene with the sort of energy and abandon that sometimes-staid NYC can use.

“I think talk of a comeback is all really people just looking back and saying, ‘You know what? We miss the energy of the early 2000s when the hip-hop movement from the East Coast had a lot of momentum,’” says rap journalist Elliott Wilson. “Like a G-Unit or Dipset or Roc-A-Fella or Murder, Inc. Once 2005 saw the end of the 50/G-Unit era, we went very much into Atlanta, Lil Jon emerged, crunk, snap, high-energy, trap. It became more of a singles market, and hip-hop’s defining tempo has been that since then. In terms of the New York sentiment, it was getting frustrating that there weren’t New York artists at the forefront of the culture.”

Stars have emerged from the New York area in the 2000s and 2010s, of course, among them Joey Badass and Pro Era, Action Bronson, and New Jersey’s Fetty Wap. But as Wilson points out, some of New York’s biggest stars looked south for inspiration. “You have Nicki Minaj, you have French Montana, A$AP Rocky,” he says. “Both French and Nicki had to go down to Atlanta to make some noise, and they weren’t trying to deliver a traditional New York sound. A$AP Rocky made it even more blatant that, he’s a guy from Harlem, but he listened to UGK and listened to screwed-chopped sounds.” All of which makes sense to Ebro Darden, Hot 97 and Beats 1’s outspoken veteran, who points to the internet as the single biggest factor in the change.

“If I’m an 18-year-old kid today, in 2010, I was listening to Jeezy, Ross, Wayne. It was Drake and Nicki Minaj on the come-up. Now, you talk to French Montana, he’s a kid from The Bronx, and he likes B.I.G., yeah, but he also likes the melodies of Tupac. You talk to A$AP Rocky, he likes Bone Thugs-n-Harmony and Gucci Mane. That’s what the internet did to the New York kid growing up in hip-hop. They were exposed to music from everywhere. So kids that are 22, they’re not having that conversation.”

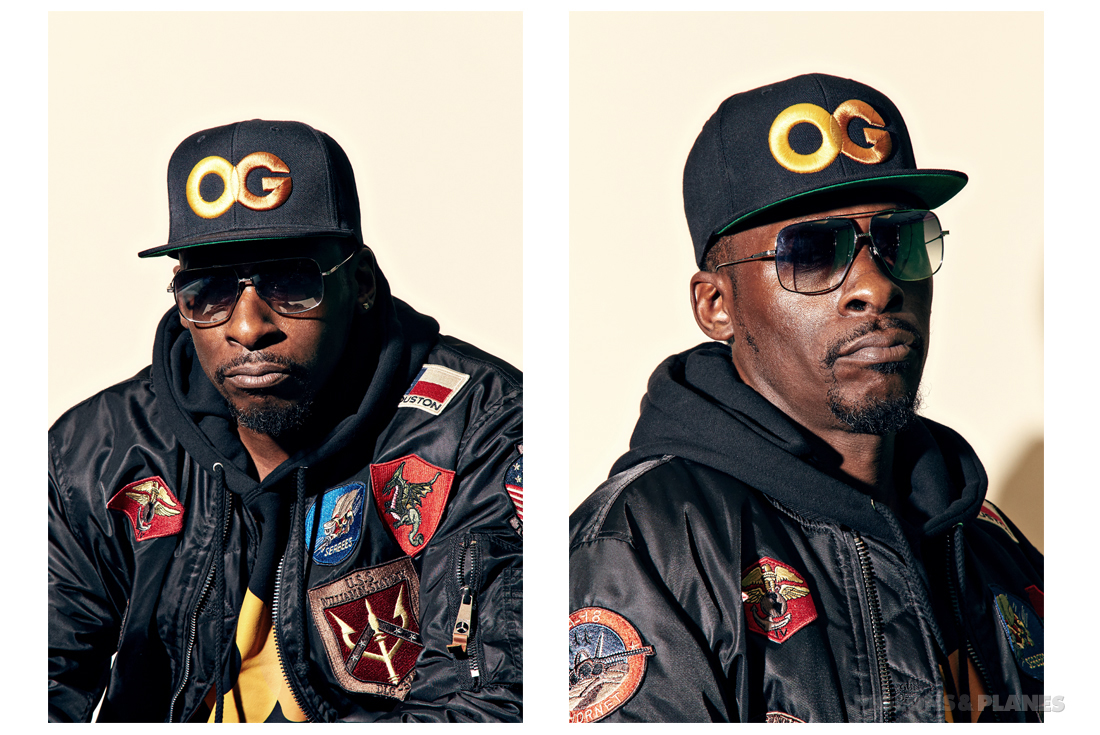

DJ Premier is happy to have that conversation. The man who is at or near the top of any list of hip-hop’s all-time great producers may be a Houston native, but he’s synonymous with New York’s “golden age” of the ‘80s and ‘90s. Premier is simultaneously a custodian of that era and actively in touch with new music.

For him, there is most definitely such a thing as a “New York sound.” “I will continue for the rest of my life to make my stuff sound like New York,” he declares. “It’s got to make my neck just pop every time that downbeat comes on. If it doesn’t do that, it’s not the New York sound.” And, he adds, “A lot of these sounds coming out of New York today don’t sound like New York.”

There are certain exceptions, though. Premier has high praise for Dave East—the pride of East Harlem by way of Queensbridge, who after five years of mixtapes (two of those years with Nas and his Mass Appeal label) recently made a move to Def Jam, with an album slated for next year.

"I JUST WANT TO BE KNOWN FOR WHOLE PROJECTS. RECORDS THAT WILL STICK WITH YOU FOR YEARS" - DAVE EAST

“Some of the younger crowd in New York, we’re starting to sound like New York again,” says East. “So that’s why I think we’re getting this attention.” East’s classic approach and the respect it has won him—his Kairi Chanel mixtape includes features by Beanie Siegel, Cam’ron and Fabolous—have led some to declare him the “savior” of New York rap, though he’s not interested in such hyperbole.

“I just want to be known for whole projects,” he says, “records that will stick with you for years.” And ones that are true to himself. “That’s what I grew up on, you know,” he explains. “Jay Z, Nas—everything they said, I believed. And to me that’s real, that’s my M.O. ‘Real’ is when your life and your music add up.”

At the other end of the “sounds-like-New-York” spectrum is the city’s most polarizing breakout star of the year. Few imagined nearly twelve months ago when “Panda” dropped, with its trap sound and Atlanta references, that the track was made by one of Brooklyn's own. Desiigner caught fire—“Panda” topped the Billboard Hot 100 in April—but there were detractors.

The irrepressible 19-year-old didn’t look back, though, getting the Kanye West and Pusha T co-sign with a G.O.O.D. Music deal, and by the summer, he returned with the mixtape New English, followed by the infectious "Tiimmy Turner,” a partly sung single which managed to tamp down those Future comparisons. The consensus on Desiigner, a year on? The jury is still out. “He’s charismatic, a great personality, he’s very entertaining to people,” says Ebro. “He does sound like Future—that’s the first thing I thought when I heard the record—but I also recognized that he’s a 19-year-old kid. Five years ago he was 14 years old and probably was a Future fan. I mean, we’re talking about children who are trying to find their creative path.” Wilson concurs: “When you see him live, there’s a star power, a young energy and a lot of talent there that still needs to be developed further. With someone like Pusha T in his corner, he’s going to continue to evolve. I think he’ll find his voice.”

Finding one’s voice in a world of blink-of-an-eye internet judgments isn’t easy, but it’s necessary. “That’s the hardest thing we all go through. How am I going to find myself?” says Erick “Arc” Elliot, beat maker of Brooklyn’s genre-pushing Flatbush Zombies. “How are people going to know who I really am? What do I rap about? What do I want to talk about? To go through that is what helps you define yourself as an artist. Those are the moments when you’re finding really why you’re doing it.”

The Zombies are one of New York’s most respected acts, and their debut album 3001: A Laced Odyssey, which dropped in March, took awareness of them to a new level. Their five-year trajectory has been steady, and they have their own fiercely independent take on what it means to “sound New York.”

“I think really what it boils down to is production and what people are influenced by,” says the group’s Meechy Darko. “Some people ride waves, but some people are just influenced by southern artists. I love UGK, we love Outkast, we love West Coast shit also. And we incorporate that in our shit. It’s like, what’s a ‘New York sound’ at this point, really? Are we all supposed to sound the same? I thought the New York style is just to be original.”

"WHAT'S A 'NEW YORK SOUND' AT THIS POINT, REALLY? ARE WE ALL SUPPOSED TO SOUND THE SAME? I THOUGHT THE NEW YORK STYLE IS JUST TO BE ORIGINAL." - MEECHY DARKO, FLATBUSH ZOMBIES

New York—a progressive city in many ways but where traditionalism often reigns in hip-hop—symbolized a generational divide that was brought into sharp focus in 2016, in two incidents spearheaded by Ebro, ever the provocateur. On February 24, rising Philadelphia artist Lil Uzi Vert refused Ebro's request to freestyle over Gang Starr’s “Mass Appeal.” The 22-year-old declared himself a “rock star” who was “not gonna rap over that type of stuff.”

“I didn’t take offense to it,” recalls Premier. “He DM’d me and said, ‘Man, anything I can learn from you, let me know. Here’s my number.’” In fact, Premier leaves the door open for the two to work together, though he adds, “It has to be the way that I do it. As a producer, you’re supposed to guide the artist to make everything glow.”

Four months after Uzi's HOT 97 appearance, the year’s most divisive hip-hop figure, Lil Yachty, again on-air with Ebro, half-assed a freestyle, asserted he’s “not a rapper,” and drew a scathing critique on Instagram from OG New York producer Pete Rock. Rock, who occupies a place in the pantheon along with Premier, called Yachty “wack” and slammed so-called “mumble rap” artists for disrespecting the culture and creating “stupid ass fans”—which in turn prompted an ageist onslaught from Yachty's Sailing Team supporters. “He comes back at us with a flurry of things on Twitter and IG,” Rock recalls. “Calling us ‘old heads’ and this and that, saying ‘those days are over,’ and all this bullshit. I don’t give a fuck. Nah, nah—a musician is a fucking musician, period. You guys can’t touch me with a candle. We opened the door for you, little man.”

Pete Rock pulls no punches about the state of current hip-hop. “A lot of these kids, they don’t give a fuck about the culture,” he says. “You know what they care about? Money.” Auto-Tune, poor lyrics, mumbled flow, a celebration of drugs and strip club culture—they’re all on Rock’s list of grievances. But topping it all is what he sees as a lack of respect for what came before. “Back in the ‘90’s the truth was real,” he asserts. “We had dignity, pride, all of that. Today? That’s totally out the window. I mean, it’s fucked up that this is the way we gotta go out, that we gotta go to our graves with this type of music on the radio.”

Premier backs up his contemporary, saying “Pete’s 100% right” about newcomers' lack of respect for their forebears, but he also seems to know that demanding respect from millennials is maybe the worst way to get it. “And I’m 50 years old,” he adds.

"IF YOU TRY TO FORCE HIP-HOP TO PLAY BY THE OLD RULE BOOK, IT DOESN'T WORK." - ELLIOTT WILSON

“How do I look beefing with a young kid? Even if you’re selling out right now and you got a crowd that’s packed—come back in five years. I’m doing twenty-plus years, almost thirty.” Wilson on the other hand, gets where Yachty is coming from. “Some of these kids are just rebelling, you know? I think if you try to force hip-hop to play by the old rule book, it doesn’t work.”

East, who’s 28, takes something of a defensive big brother stance on the issue, suggesting you can’t force music history on young people. “They all got they own lane,” he insists. “He’s 19! You can’t get mad at somebody for being themselves. Just because you were a fan of Biggie don’t mean the next person had to grow up to Biggie, or listen to Biggie, or even know who Biggie is.”

If there’s one thing that it seems everyone, young and old, can agree on, it’s love for Young M.A. New York’s unlikeliest new star was also its most winning—a gritty bar-spitter, unabashedly gay, from various Brooklyn locales but who spent a good part of her youth in the South, she represented her native borough like no other. “She’s in that tradition of a vicious rapper, her bars are incredible,” says Wilson. “When you meet her, you know right away there’s something special about her.” “She keeps it hood,” adds Premier. “And I love that.” M.A had already been on the come up for a couple years, but “OOOUUU” blew the doors open, a late-spring and summer smash that launched a thousand remixes and loads of high profile fans, including Nicki Minaj, Remy Ma, Jadakiss, Uncle Murda, French Montana and Young M.A’s personal hero, 50 Cent.

"IT'S THAT TIME FOR NEW YORK TO GET BACK TO BEING ON TOP AGAIN." - YOUNG M.A.

“He was straight New York City,” M.A says. "The first song I heard was ‘Wanksta.’ I was like, ‘Who is this?’ And it wasn’t until I seen the video that I was like, ‘Yo this dude is dope.’ I just thought he was the flyest, the swaggiest dude ever. The way he flowed, the way he spit, the things he say, he was just like, cool.” All things that could be said right now about M.A herself, who proudly stands for her city. “It’s that time for New York to get back to being on top again,” she says. “And that doesn’t discredit the South or West or Midwest—they're going to do what they do. But I’m from New York City, and I gotta rep New York City.”

At the same time, as much as M.A’s street style may excite rap purists, she takes a live-and-let-live attitude to other sounds. “I have nothing against Lil Yachty or the other guys, I listen to that music from time to time,” she concedes. “It’s a club type record. But to me hip-hop is separate, and what they do is their own thing. And basically, if you don’t wanna hear it, don’t listen to it!”

Meanwhile, Joey Badass, hailed four years ago by traditionalists as a latter day boom bap disciple thanks to his work with Premier on Summer Knights track “Unorthodox” and B4.Da.$$ cut “Paper Trails,” has since moved beyond such, well, orthodoxy, into more melodic and danceable directions with tracks like “Teach Me” and this year’s “Devastated.” As for that evolution, Premier isn’t bothered. “If you want to have a couple records that veer off or whatever, that’s cool.”

If there is a sweet spot between bars and melodies, between the street and the club, twin tyros A Boogie Wit Da Hoodie and his cohort Don Q, with whom he released the collaborative mixtape Highbridge the Label: The Takeover, Vol. 1 in May, seem to have hit on it, each bringing his own skills to the table and proudly waving the flag for their Bronx stomping ground. “Their styles are very compatible,” says Wilson.

“Don is more straightforward bars and A Boogie is kind of more melodic in his approach, so it balances out. Then with these guys Bubba and QP that run the label, they’re like this family unit. They’re really just out there trying to be the new Roc-A-Fella, the new Ruff Ryders. And they’re from The Bronx, the home of hip-hop. So it’s cool to see.” The bright, bouncing “My Shit” put A Boogie on the map, his Artist mixtape featured remarkably sentimental standouts in “Friend Zone” and “Still Think About You,” and the kid got an unexpected high-profile cosign in August, when he was invited by Drake to open at Madison Square Garden. A September New York Times feature even posited that A Boogie may be the one to drag New York at long last into a modern sound. So to paraphrase the great James Todd Smith, do we call what New York City is enjoying a “comeback”?

“To me, that shit about a ‘comeback’ is like—‘Huh? We never left,” offers the irascible Pete Rock, who next year will reunite for another record with longtime partner CL Smooth. Similarly, Dave East says he doesn’t get too caught up in such talk. “Back when Jay Z was making his music, or Nas was dropping, they wasn’t trying to ‘bring New York back,’” he explains. “They was just making their music.” The ground swell of new talent from New York—other names on the horizon include Brooklyn’s Curly Sav & Dah Dah, Topaz Jones, Jimi Tents, Leaf, and Justin Rose—is inspiring for those of us who have long called NYC home.

And maybe most importantly, despite some grumbling from the old guard, the melting pot is finally coming around to the idea that hip-hop is a big tent with room for everyone. “The thing is, this is music,” say Flatbush Zombies’ Arc. “And there are no rules to anything. Because who the hell is anyone to say you have to do anything?”

Like the city’s skyline—the most iconic in the world, but also ever-evolving—having a vital music scene means being open to change. Even Premier, the keeper of the New York hip-hop flame, agrees that there are many lanes. “If you want an apple, buy an apple,” he concludes. “You want an orange, buy an orange. And some people want both.”