Artistic geniuses are often not fully appreciated in their time. We are only now beginning to reckon with the sublime beauty of the music of hip hop producer J Dilla, who died of a rare blood disease in 2006 at the age of 32.

Though Dilla enjoyed a significant cult following while he was still alive, he has since ascended to the status of patron saint of the MPC. His influence on hip-hop, jazz, and other genres has expanded thanks to the devoted work of his mother, Maureen “Ma Dukes” Yancey, musicians like Robert Glasper, and academics like Dan Charnas.

Charnas produces the VH1 show The Breaks, authored The Big Payback (the definitive text on the history of the hip-hop business), and teaches at NYU. This past spring, he designed and led a seven-week course called “Topics in Recorded Music: J Dilla” that sought to unpack Dilla’s conception of rhythm—which Charnas calls “Dilla Time.” He describes it as "essentially what happens when ‘straight’ song elements are put deliberately into conflict with ‘swung’ song elements.”

The class began with a three-day trip to Dilla’s native Detroit to learn about his familial and cultural underpinnings. Then they returned to New York City, where Charnas put his 18 students to task exploring the nuances of Dilla Time through the creative medium of their choice—whether it be beatmaking, film, event planning, or web design.

Charnas spoke with us about the inspiration and construction of the course, and how his appreciation for J Dilla grew alongside that of his students. See portions of the projects that his students produced below and continue for our interview with the professor.

Student project: Dilla Time 'Ruff Cut' Short Film

Students Jesse Motitz and Gabriel Fraivillig translated Dilla Time to the medium of film editing. Their short film, Ruff Cut, can be seen above. They explain: "Jesse created a split frame. Using an anamorphic aspect ratio, he created a frame that was doublewide. The shot on the left represents straight time, cut in normal, regular intervals, matching the tempo of the song. Nothing new there. But the other shot on the right was cut to the snare, designed by Gabe to fall out of sync with straight time. It isn’t through one of these shots or the other that Dilla Time is illustrated, it’s through the dissonance between the editing of both shots that the translation is achieved."

Student project: Dilla Data Website

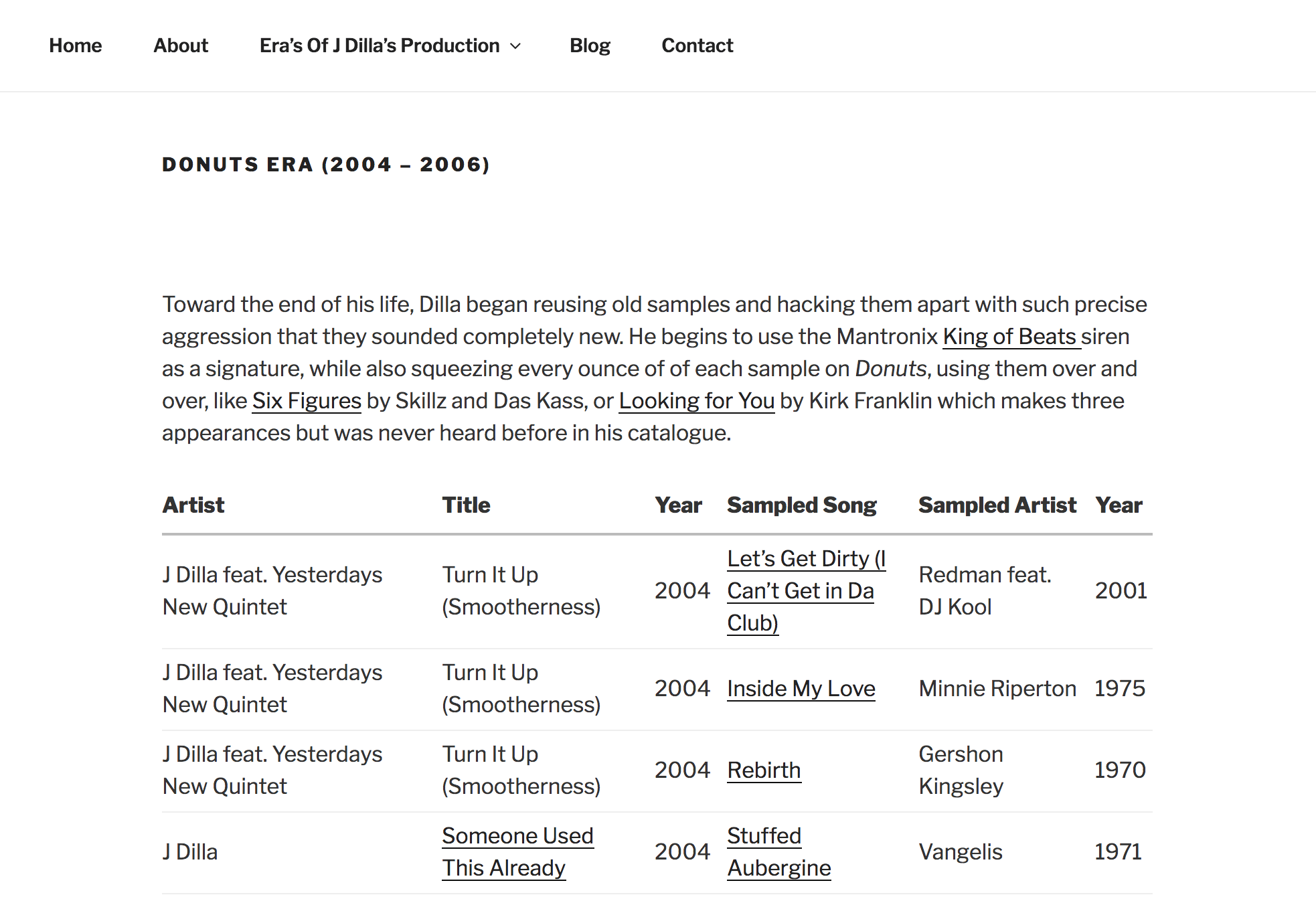

Four students created a website that lists everything Dilla sampled in his large catalogue of work, broken down into six of his production eras. Thinking back on the process, they explain, "Unpacking his career in this fashion is surprisingly emotional. It’s as if we are reading his own personal diary of his life and feeling his own nostalgia and curiosity. As a man of few words, Dilla’s life is communicated not through conversations or interviews, but by his musical expression." This project was created by Owen Smith-Clark, Jordan Taylor, Kay James, and Jack Harrison Kleinick. You can see the site for yourself here.

You’ve called J Dilla one of the "Three Kings of American Rhythm," along with Louis Armstrong and James Brown. In your mind, what makes Dilla so great that he warranted an entire class?

I began teaching at NYU’s Clive Davis Institute full-time in 2013. Even though I was brought there because of my expertise in hip-hop, my main duty is to teach the freshman core history course on American pop and the American music business. As part of doing this class, you begin to think very archetypically about what moved music forward. At the same time, you respond to students’ favorites and what they're interested in.

These are kids that were born in the late '90s, after Tupac and Biggie died. Yet, over the years, I've found that so many of them are acolytes of Dilla. So I decided in the very last class of this 14-week history course to do a lecture on Dilla. It was very popular and I found that the students responded to it. So we decided to turn it into a full-blown class this year.

these are kids that were born in the late '90s, after Tupac and Biggie died. Yet, OVER THE YEARS, I'VE FOuND THAT so many of them are acolytes of Dilla.

But for me, it was personal, too. I had actually worked with him for a short time back in 1999 when I was producing Chino XL for Warner Bros Records. It’s not like I had a huge personal relationship with him, but I was always glad before he passed that I was able to tell him that he was my favorite producer. I like to listen to music but I can’t listen to lyrics while I’m writing, so I ended up listening to a lot of Dilla beats. When you listen to things over and over again, you begin to hear deeper into them.

If you’ve ever made a beat and listened to loops over and over again, you begin to hear different things. Dilla had been my favorite producer, but I finally began to hear what it was he was doing. Not just with his various production techniques, not just the interesting things he did with harmony and melody, but for the most part, the uncanny things he was doing with rhythm. I really started to realize the genius of the man.

A lot of that experience went into creating this curriculum for the Dilla course. It was based around his central innovation, which I had to label as something. So I called it Dilla Time. In the simplest explanation, it's the deliberate juxtaposition of straight and swung song elements. Basically, turning a grid against a grid. That is that limping, drunken feeling that you hear when you listen to a Dilla beat. You’re hearing straight elements and swung elements put into conflict with each other in a deliberate way.

I've also spent a lot of time in Detroit. And every time I've been in Detroit, I've thought about him. I've developed a relationship with people in the city—this exhilarating, frustrating, hopeful, desolate city. And I thought, you really can’t understand America without understanding Detroit and you really can’t understand American music without understanding Detroit music. So, how would you be able to understand Dilla without going to Detroit? Instead of trying to Skype everybody in or fly everybody in, I thought, "Let’s just all go to Detroit!" I was lucky enough to have the support of the administration at Tisch, the administration at Clive Davis Institute, and Jason King, who runs the history area of the Clive Davis Institute.

we had a chance to hang with some of Dilla's family and we got some professional history from people who had worked with him.

So, during spring break, we flew to Detroit for three days. Ma Dukes was supposed to come meet us there, but there was a huge blizzard, and everyone was late getting into Detroit. She lives in Puerto Rico now so she couldn’t get a plane in from Puerto Rico, they were all cancelled. So we had to go up to Channel 4 and use their conference room and pack everyone so she could talk to us via Skype.

But we had a chance to hang with some of Dilla's family and we got some professional history from people who had worked with him. We also did some amazing things with other Detroiters of note. We had a breakfast meeting with Steven Henderson, who is the Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist for the Detroit Free Press. We got a tour of the Motown Museum with the legendary Funk Brothers musician Dennis Coffey. We got a personal tour of the Techno Museum from Cornelius Harris. We got lectured on Detroit history and Detroit music by Roger Robinson, who was one of the people to save the Phelps Auditorium—where P-funk first formed. So all of these tendrils of history came together for us in Detroit.

After these three days, we went back to New York and actually had the class. The course was a seven week course that went through different phases of Dilla’s career. The centerpiece was a class on "Dilla Time" that I co-taught with Jeff Peretz and Nate Smith, the drummer for Jose James and other artists. Jeff talked about the theory of Dilla Time works, I showed how Dilla would do it on an SP-1200 and an MPC, and Nate Smith showed how he approaches it as a drummer. It was fucking amazing. That part still gives me chills.

So that was one of seven courses we had. Tre Hardson from the Pharcyde came in to to tell us about the early career of Dilla. Brian Cross, who took some of those great latter day pictures of Dilla, talked about taking him to Brazil, some of his last days in Los Angeles, producing the Suite for Ma Dukes after his passing—

Wasn’t that Miguel Atwood-Ferguson?

Miguel Atwood-Ferguson is the person who composed it. We did not have time to talk to Miguel, because our schedules weren’t aligned, but we talked to Brian Cross, who produced it. Brian is the person who got the money and made it possible for Miguel to actually compose that suite.

We also talked with Rhettmatic, who was a part of the Beat Junkies crew who sort of played host to Dilla for the last phase of his career. And we talked with Perrin Moss of Hiatus Kaiyote about how his influence has now gone out into traditional music making.

And now I’m getting back to your question: Why do I teach Dilla as one of these three kings of American rhythm? One of the reasons is a basic approach to how rhythm is handled in pop music. Louis Armstrong basically established that swing would be the rhythmic approach to American pop music. Not swing the genre but swing, the relationship to time.

Even some of the musicologists who are doing work on microrhythms have not properly credited Dilla as a source of a lot of this stuff.

Then, machines entered rhythm and introduced the rigid grid, which forced man to understand how he was going to deal with machines in terms of making music. There are different ways of doing it. You can give yourself over to the machine entirely and your music will sound like Devo. Or you can do it like Prince did it in “Lady Cab Driver,” where you have the LinnDrum playing the hi-hat and the clap. But Prince is hand-playing the snare against it. So you get an eerie kind of man-and-machine thing on that song.

And then you do what Dilla did, which was unprecedented. You take all the power and quirks of the machine to take one grid and another grid and play them against each other. That’s what you hear when you hear a song like “Pause” or “Come and Get It” with Elzhi. That rushed snare—but sometimes it’s not a rushed share. Sometimes the snare is straight and he’s swinging some other elements.

So, this is what we did in class. We analyzed this music, really for the first time. What I’m really excited about is, instead of me just creating this curriculum and teaching students like, "I’m the important professor of blah blah blah," I’m like, "Y’all gotta do the work."

There is very little written on J Dilla. Jordan Ferguson did an amazing book on Dilla and there have been magazine articles written, but very little theoretically about what Dilla is doing. Even some of the musicologists who are doing work on microrhythms have not properly credited Dilla as a source of a lot of this stuff. So, that’s what I asked the students to do.

So the idea was, "Okay, you’re going to come into class and you’re going to produce two pieces of work. You’re going to do a term paper that expands the knowledge of Dilla in some way, and a creative project."

There was one student who wrote about the similarities behind Dilla and Nujabes, the Japanese producer. And there was somebody else who wrote a paper on the relationship between Dilla and Madlib, and how that influence was actually mutual, not one-way. This student did great work talking about “persistence of vision” in film and how it relates to what Dilla is doing in terms of “persistence of sound.” I mean, to me, that’s graduate school-level work. That’s music journalist-level work.

why do I teach Dilla? Why is he important to American pop music? Because he's the first electronic music producer to literally affect the way that traditional musicians play their instrument.

So those were the term papers. And then you had the creative projects, which was, okay, you guys are going to play to your creative strengths. Because most of them are art students. So if you’re a filmmaker, you’re going to make a film. If you’re a beatmaker, you’re going to make a beat. And if you like to work on the web, you’re going to make a website. And if you like to do live events and you’re interested in business, we’ll do that. And that’s what we did! We split everyone into groups, and they did these great group projects.

So that’s the class. It was a seven-week experiment, plus the time we did in Detroit. And as far as I know, there isn’t another course being taught on Dilla, although I do know that my man Raydar Ellis, at Berkeley, does the Dilla Ensemble, which is dope.

So why do I teach Dilla? Why is he important to American pop music? Because he's the first electronic music producer to literally affect the way that traditional musicians play their instrument. Think about it.

That’s absolutely true. Our appreciation for Dilla grows every year.

For a guy who never had a top 20 pop hit, it’s stunning. Stunning!

What did you yourself get out of planning and teaching the class? What did you learn?

Number one, to be forced to really put into words what Dilla’s contribution was. But the second is to learn what it’s like to be on the edge of research for something. Even though I wrote The Big Payback, I certainly had a lot of folks cut down trees and lay down roads before me. This is an area that is newer, so it is humbling and challenging, but also kind of an exhilarating experience to think about how to responsibly talk about this guy’s legacy.

I learned along with the students. I taught them and they taught me.

What I got out of it was the sense that we are just beginning to understand who Dilla is. Also, I met Maureen very, very briefly back in 1999 when I came to DIlla’s house. But to be able to talk with her, to be able to meet with members of Dilla’s family, to be able to talk to people who are lifelong friends and associates with Dilla—it’s a real honor. Also just the fanboy shit, of like, I talked to Perrin Moss! Oh, shit! Hiatius Kaiyote’s my favorite group right now, like yooo! And to have him say the music he listened to was The Roots and Common and Erykah and stuff like that, and I didn’t know that the common thread was Dilla. I learned along with the students. I taught them, and they taught me.

Dilla Time itself is a somewhat nebulous concept. There’s a lot to unpack, and they must have a lot of unique perspectives and insight from their different backgrounds that they have to offer.

Because I’m 49 years old and they’re 19, 20, 21. Of course! And they make connections that I can’t make. And vice versa. So I think it was really good.

Student Project: Beatmaking

Six students created beats to represent different Dilla production techniques, and recorded demonstration videos of the process. You can see Gabe Simon's in-progress "Mona Lisa" beat process in the video above. Cooper Pearson, Ethan Grey McIntyre, Luca Medici, Gabe Simon, Lucio Westmoreland, and Allah Joseph worked on this project.

Student Project: Dilla Foundation Charitable Event

A group of students created a plan for a charitable, Dilla-themed event featuring DJ sets from Karriem Riggins, Robert Glasper, Questlove, and Madlib—inspired by Jay Dee’s work and samples. All proceeds of the event would go directly to the Dilla Foundation.

Above, you can see mockups for merchandise created by Meredith Stein, who redesigned a logo for Uncle Herm's Donut shop: Dilla's Delight's. Stein says, "I remembered Uncle Herm talking about the significance of the Donut to J Dilla. He mentioned that people would call 45’s ‘donuts’, so I imagined a donut in place of a 45 on a record player." Charlie Bird, Gabe Feller-Cohen, Meredith Stein, Marcus Klein, Jackie Paladino, and Charles Eduard O'Neill worked on this project.