1.

Image via Dana Paresa

By Drew Lindsay

“We used to call it being ‘open.’ Of course the weed had something to do with it. But once you’re open, you’re just clawing at the edges of… of everything, you know what I mean? Pushing the very envelope of what you can say and what you can’t say. You can say anything when you’re open.” –Self Jupiter (Freestyle Fellowship)

September 28, 1999: Method Man and Redman released their first collaborative album, Blackout. On the sixth track, “Cereal Killer,” Method Man starts the first verse in storytelling mode. He enters some house while a family is asleep. He disconnects the power, finds a butcher knife, and creeps up the stairs with his “prey unaware.” The verse stops before he finishes, but I’m pretty sure he decapitates the entire family and hangs their heads by the chimney.

I love that song.

One reason I love it is because it reminds me of Freestyle Fellowship, a group I fell in love with when I was about 15. The video version of their song “Hot Potato” starts as a classic posse cut—four emcees describing and demonstrating their vocal superiority (and also comparing hot women to different types of potatoes)—and ended as something else: MC Self Jupiter climbing the stairs of somebody’s house, finding a woman alone in a room, and dismembering her. The video faded out at that point, but their album Innercity Griots had more of the same on tracks like “Six Tray” and “Way Cool.”

I loved that album.

That album reminded me of “4 Better 4 Worse,” Pharcyde’s classic rap-as-relationship metaphor track. (Self Jupiter told me that the similarity was no coincidence—“they got that from us… from me particularly”). In the first verse of the Pharcyde song, Slimkid3 marries his high-school sweetheart, “Rhyme A Linda.” By the third verse, a cracked-out Fatlip is in a phone booth prank-calling some woman, telling her he’s going to take a hammer and drill her skull, lick the meat off the bone of her leg, and then stick his fist…

Well, anyways… I loved that song too.

As a way of understanding this music, try to imagine Method Man—a veteran of Wu-Tang’s grimy, flickering-lights-on-the-subway, coke-snot-out-your-nose hood rap—surveying the hip-hop landscape in the year 2000: everybody was hood, everybody was gangster, and everybody was one of the best if not the best murderers of all time. Method Man and Redman’s response was simple: “Oh—I see. Everybody’s a gangster? We’re fucking monsters. You shoot people? We kill whole families. We take nuts and screws out of fucking Ferris wheels.”

I got it—from the first time I heard it, I got it. And I loved it.

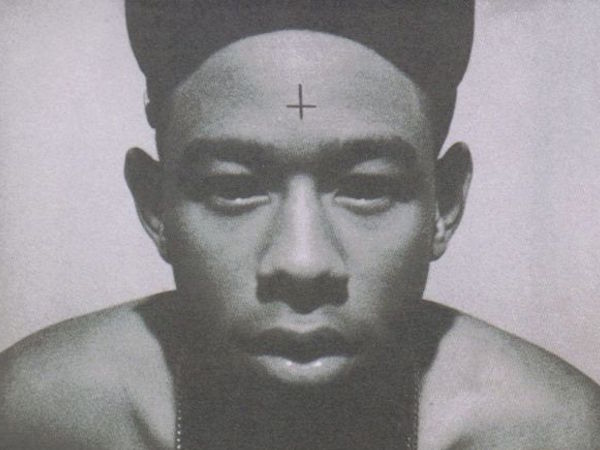

September, 2015. It’s been 22 years since the release of Bizarre Ride II the Pharcyde, and Tyler, the Creator was just banned from the United Kingdom for 3-5 years for offensive lyrics (and the resultant “incitement” of his music). The British Office In Charge Of Banning People, or whatever it’s called, specifically mentioned the song “Tron Cat,” which contains one of Tyler’s more notorious lyrics (involving rape, a pregnant woman, and the word “threesome”).

My intention in this article is not to debate free speech; if there is a better defense of free speech than Nadine Strossen’s in this article, I haven’t seen it. I intend, rather, to offer my own eulogy of Tyler’s (and Earl Sweatshirt’s) psychotic, murderous, misogynist personas as they pass—apparently extremely gently and willingly—into the night.

I’ve seen numerous quotations from Earl Sweatshirt and Tyler in the past few years referring to the “immaturity” of their earlier albums. Tyler’s responses to the U.K. ban have echoed that sentiment: “I never play those songs,” and “it’s based on things I made when I was super young.” In a Grantland article, Rembert Browne assumed a similar logic, comparing Earl’s first album to “jokes” made by “teenage boys,” and equated a turn toward more autobiographical material with “maturity.” Earl agreed, saying, “I can’t be talking about raping people and shit. That shit’s crazy.”

Tyler’s point that he hasn’t played these songs in years is valid. But something about Tyler’s response to this ban—and Earl’s attitude toward his younger Odd Future days—bothers me. It bothers me because… well, I liked that old stuff. What can I say? I feel like they’re telling me I shouldn’t have.

The first two years I followed Tyler on Twitter, all he did was make fart jokes, so it’s entirely possible he has matured personally. And Earl has unquestionably matured musically. “Hive” is light-years more sophisticated than “Earl.”

But here’s the problem: Tyler’s “Yonkers” is a great song. It’s an important song. The majority of successful hip-hop artists will go their whole careers without a song that good. “Tron Cat” was good, too. It’s hard to separate “Rella” from its visual treatment, but the world is a better place because that song/video exists. So in response to the U.K. ban, rather than saying, “I don’t do that anymore,” I think I’d prefer, “You don’t know what the hell you’re talking about.”

I teach a course on hip-hop at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and when I ask my students why they like Tyler’s music—his awful, misogynist, psychotic, murderous music—their first response is “because it isn’t real.” As first responses go, that’s an important one. Tyler’s music, in other words, is not meant to describe real life—it has a different purpose.

To understand that purpose, however, we need to push past that initial “fantasy” analysis. And here it can be productive to compare “Yonkers” to a song like “Bonnie and Clyde,” because my students have similar initial responses to Eminem—they “don’t take it literally.” Tyler and Earl have both made it clear that Eminem was an inspiration for them, but I tend to think that the comparison to Eminem (not as a lyricist, but conceptually) works more in Tyler’s favor.

7.

Image via Wikipedia

It’s one thing for an audience to recognize something as fantasy. But we still have to argue why it’s a worthwhile fantasy, don’t we? In a song like “Bonnie and Clyde,” I get it—Eminem isn’t really going to murder his baby mama then drive to throw her body in the lake with his baby daughter in the backseat. This is all in his head. OK… but now what? In terms of concept, I like Eminem in the way that I like purposefully exaggerated things—it’s funny. But I don’t think about it much more after that. Sometimes my students say, “It’s like the dark fantasies we all have.” [Author’s note: I don’t have these fantasies.]

The difference is that Tyler’s fantasies matter.

All rap is a response to the rap that came before it. “Yonkers,” like much of Tyler’s music, should be read as satire. Satire depends on shared cultural understanding and shared cultural expectations. It’s a type of art that violates or attacks those expectations.

The psychotic world Tyler creates, and our reaction to it, exposes our culture’s odd relationship with hip-hop misogyny: we’ve grown accustomed to sexual objectification and single-dimensionality—the stuff most clearly representative of real-world problems that we see every day—and yet Tyler’s ban from the U.K. proves we have a harder time tolerating the absurdist stuff that is so obviously unreal. Tyler’s music provokes that conversation.

Tyler doesn’t just mock standard hip-hop conventions. He attacks them, destabilizes them, and offers something new in the deconstructed space.

In the context of hip-hop (one of the last bastions of popular culture openly unsympathetic to homosexuality) Tyler angrily calls people “faggots” in one line, then raps about dancing around in panties in another: “I’m not gay, I just wanna boogie to some Marvin.”

In the world of hip-hop where you can’t show any weakness, where you can’t be a whiny little bitch, Tyler bases an entire album around a meeting with his therapist. In the “Yonkers” video, he eats a cockroach, vomits, and hangs himself.

In the world of mind-boggling hip-hop popularity, a world that blasts static images of black culture to millions of eyes around the world in order to sell them, do you know how much it matters for an artist to be different? And it’s not just different for difference’s sake. Tyler doesn’t just mock standard hip-hop conventions. He attacks them, destabilizes them, and offers something new in the deconstructed space. All of this matters.

I don’t think people have to like Tyler; oddly, I expect people not to. His art generates a very peculiar response—you feel like you might be the only person in the room who gets it because it’s so fucking out there. The irony, though, is that a lot of people feel that way. He built an astonishingly large fan base on the strength of songs you couldn’t play within 100 miles of a radio station. That sort of unpredictable fandom usually signals something that matters, something that deserves a closer look

I don’t mind Tyler (and Earl) moving on to new approaches. It makes sense that they would. But as we bid farewell to their utterly bat-shit personas, it’s important to understand where they were coming from, and recognize why it mattered to so many people.