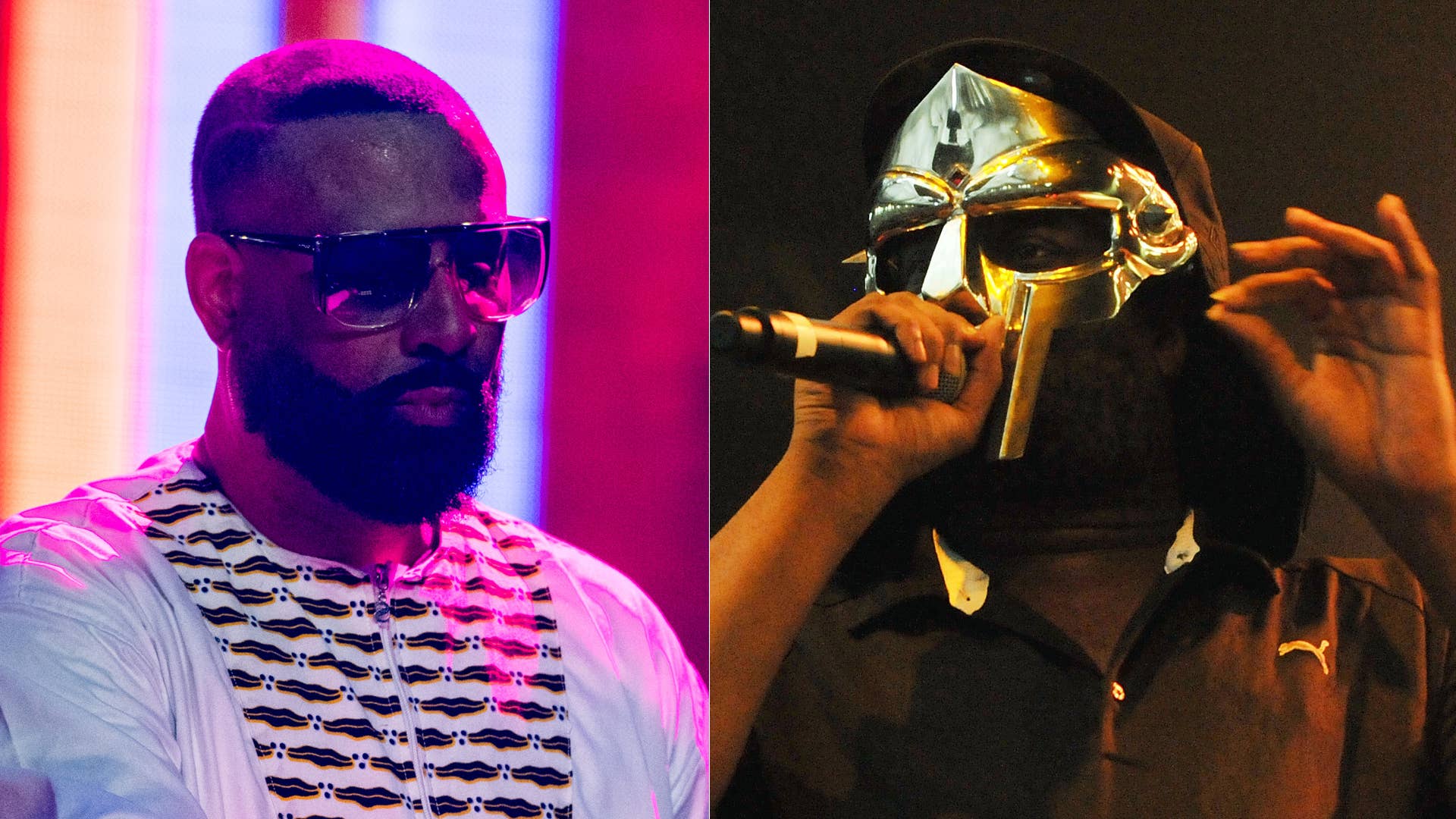

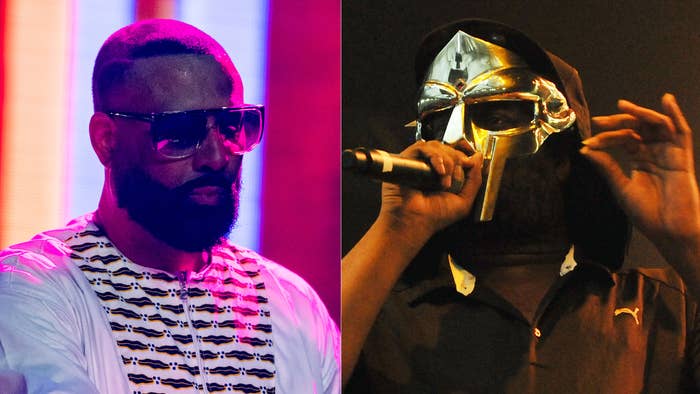

Madlib and MF DOOM are two artists shrouded in myth. The former is a master beatsmith with a global ear capable of finding a sample in the most obscure places. The latter has rhymed under so many different aliases it’s hard to keep track. The 2004 album they made together, Madvillainy, is the legend behind all that mythology.

Madvillain’s Madvillainy, from Bloomsbury’s “33 ⅓” series (other installments break down albums as monumental as J Dilla’s Donuts and Janet Jackson’s The Velvet Rope) parses some of the folklore behind that legendary project. In the spirit of DOOM, author Will Hagle employs pen names and “alternating perspectives of three music journalists who work for a fake publication called The Daily Daily” to do so.

Part of that story revolves around the involvement of Walasia Shabazz, a founding Complex editor and senior editor whose Stress Magazine interview helped set in motion the chain of events that led to DOOM and Madlib teaming up. Hagle credits her as the A&R of his book, but this excerpt from it shows why, besides a cryptic credit on “Fancy Clown,” Shabazz been fighting to have her contributions more fully acknowledged—by Stones Throw Records, lore-reciting rap nerds, and everyone who thinks they know what really went down when the project was just an inkling of an idea.

“That’s how Madvillainy should be viewed: One third DOOM, one third Madlib, and one third Walasia Shabazz,” she tells Complex. “Everything else is industry rule number four thousand and eighty. Half of the story will never be told, and what I told Will Hagle was just the tip of the iceberg.”—Melvin Backman

Can the story of Madvillain’s formation be as simple as: Two underground hip-hop artists signed a record deal with Stones Throw as their careers were hurtling toward respective crests and created an album together? Those are the facts. The indisputable truth. But Madvillain consists of MF DOOM and Madlib. Their origin story must be more grandiose.

Over time—through versions of the narrative shared in articles online, often featuring representatives from the label as the closest primary sources—a specific version of Madvillain’s origin story has been cemented as Truth. This rendition tends to omit a key individual. Her perspective remains untold. She is unseen.

Most accessible online retellings of Madvillain’s pairing describe Madlib mentioning his desire to work with DOOM during an interview with Marc Weingarten at the Long Beach aquarium, where he also mused on the psychedelic nature of sea dragons. In that Los Angeles Times profile, which ran in the Jan. 20, 2002 edition of the paper, DOOM’s name does not appear. It is written, however, in another article from a month or so prior.

The article, published in Mass Appeal, has a byline with the name “Miranda Jane.” Now, the author is called Walasia Shabazz. She’s credited for her vocal contribution on Madvillainy’s “Fancy Clown” as Allah’s Reflection. Unlike other music journalists, with whom Madlib does not enjoy speaking, Walasia connected with her subject on multiple levels. She grew up in LA, near the Lootpack and other Oxnard artists. Her parents, like Madlib’s, were musicians. Buell Neidlinger, a jazz and classical cellist and double bassist, was her father. Neidlinger met Walasia’s mother, a drummer named Deborah Fuss, through their mutual friend Peter Ivers, founder of LA’s experimental new wave movement.

After high school, Walasia moved to the Bay Area. She befriended A-Plus, the Oakland rapper from the collectives Souls of Mischief and Hieroglyphics who happened to have a bootlegged copy of KMD’s Black Bastards. In the mid-’90s, when label politics still obscured that LP’s greatness from public consumption, it became one of her favorites. She and A-Plus would listen to it on repeat. DOOM provided for her a consistent soundtrack before he entered her life.

Walasia soon started writing for an Oakland hip-hop magazine called 4080. Later, she became the West Coast editor at Stress. Her bylines grew. In 2000, she received an assignment to interview MF DOOM and MF Grimm in the San Fernando Valley, where they were working on music together, purportedly for a new incarnation of KMD.

“The reason they were out there [in L.A.] working, trying to get all this done was because Grimm had already been sentenced and was going to have to go to the penitentiary for a long time,” says Walasia. “They both kept in touch with me [after the interview]. Both really became my friends, and we kept in close touch. When I found out that Grimm was going away, he asked me if I would come to New York.”

In the subsequent months, Walasia formed a personal relationship with both DOOM and Grimm that evolved into business beyond press coverage. After moving to New York to take a role as an editor at the newly established Complex, Walasia would make frequent trips to visit Grimm at Fishkill Correctional Facility in Beacon, New York, upstate. Although DOOM lived in Georgia, he would take the train to New York with an oversize bag of gear to make music and hang out with old friends. After DOOM asked Walasia to be a financial conduit between him and Grimm, she became DOOM’s manager.

Regardless of how many people DOOM enlisted to maintain operation of his business’ loose structure, for Madvillainy’s purposes, Walasia was the most important. In New York, she had entrenched herself in a social scene revolving around hip-hop and the music industry. DOOM would accompany her to events and parties. Sometimes in the mask. Sometimes barefaced. Always a mysterious bundle of sweet, bizarre energy.

By late 2001, when Walasia was in the bomb shelter to interview Madlib for the Mass Appeal profile, she had been working with and for DOOM, while continuing to cover artists like Madlib for her music writing assignments. Although Madvillainy would take years to develop into its final form, she was an initial catalyst.

“That was the article that started it all. The last question I asked, I even turned off the tape recorder. And then I was like, ‘Wait, I forgot one thing.’ And I turned it back on. I said, ‘If you were able to work with anybody, who would you want to work with?’ And I don’t remember who else he said, but I remember he said ‘DOOM.’”

In the article, DOOM’s name does appear as an artist Madlib mentions enjoying. The other artists he says he aspires to work with are Kool G Rap and Q-Tip. Because of Walasia’s intimate knowledge of DOOM’s personality and music-making process, his was the name that stuck with her.

“I said, ‘I know he would love to work with you, and you guys will be perfect to work together. You remind me of each other a lot. I’m gonna hook it up. I’m gonna get it together. We’re going to do it. We’re going to do some kind of album or something really cool. It’s going to be really different and avant-garde. We’ll do some really stylistic cool shit,’” says Walasia.

Whether it happened before, during, or after Walasia’s interview at the bomb shelter, Madlib’s desire to work with DOOM caught the attention of Stones Throw. As did his mention of Jay Dee, or J Dilla, a like-minded producer from Detroit who happened to reciprocate Madlib’s reverence. Dilla was another kindred soul. A beatmaker who melded sounds together in ways no others conceptualized.

“It took [Madlib] saying he wanted to work with DOOM and Dilla outright in order for us to kind of shake off the cobwebs, and for me specifically to say, ‘Well I can definitely make the DOOM thing possible, at least in theory,’” says Eothen “Egon” Alapatt, who worked at Stones Throw during the Madvillain era.

Egon saying “me specifically” refers to the common legend that he had a friend in Georgia—the Jon Doe thanked in Madvillainy’s liner notes—who made the introduction. Although Walasia deserves to be Seen more than she has, Doe’s catalytic role is concurrently true.

“Jon Doe” is the stage name of DJ and rapper Jon Foster. Foster grew up in 2007’s “Best Place to Live in Rural America,” according to Progressive Farmer Magazine: Glasgow, Kentucky. Not a flourishing hip-hop metropolis. But Foster loved the music and by the mid-’90s had become an avid record collector with a weekly spot at Western Kentucky University’s radio station. In 1999, Foster moved to Nashville, because he “just wanted to get the hell out of Kentucky.” He met Egon, introduced him to MF DOOM’s music via the Fondle ‘Em singles, and formed a friendship over their shared interests. After Egon finished college and left for L.A. to work for Peanut Butter Wolf, Foster moved to Georgia. Both continued carving out their respective lanes in the industry. Settled into his new neighborhood in Kennesaw, Foster heard that the hip-hop legend he and Egon had obsessed over lived a five-minute drive from him. He met Daniel Dumile when their mutual friend Count Bass D brought him over.

Foster claims he and Dumile hit it off right away. As time went on, they would hang out with each other at their respective houses, drinking and smoking weed and listening to records. They did a song together in early 2003 called “The Mic Sounds Nice.”

Throughout their friendship, Foster never lost his fandom and respect. “I’m like, ‘This is fucking Zev Love X. This is fucking DOOM. What’s mine is yours, right?’” Foster says. “Every time I went over, I’d take a stack of 20 or 25 records and just give them to him just because, or I’d be like, ‘Yeah, if you find something, feel free [to use it].’” Foster would hear sounds from some of the records he gifted DOOM on MM…FOOD. This aligns with stories about how DOOM sampled from Bobbito’s collection for DOOMSday or how he and Subroc combed Dante Ross’ crates for Mr. Hood and Black Bastards. Like Madlib, DOOM ingested whatever records found him, regurgitating tracks in altered form.

“[In early 2002, Egon] called me and was like, ‘Hey, Otis is interested in potentially working with DOOM. I heard that you kind of know him. Could you maybe help?’” Foster says. “I was excited about the idea. This would be fucking incredible if these guys work together. Very selfishly, like a fan, I just wanted this shit to happen.”

Foster asked Egon to put together a package of Madlib’s records. With the package on the way, Foster asked DOOM if he’d heard of Madlib. Yes, he’d heard of him. No, he’d never heard him.

“DOOM didn’t know anybody’s shit,” says Foster. “He’s the quintessential artist. He’s focused on what he’s focused on.”

When the box arrived, they huddled over it in DOOM’s driveway, late at night. “I was like, ‘Okay, here’s the Lootpack album. This is what this is about. Here’s the Quasimoto album. This is some funky shit I think you’ll be into. Here’s the jazz stuff.’ Kinda tried to break it down,” says Foster. “That was really it. I didn’t hear anything about it until maybe six months to a year later. Like, things are working out. Then Madvillainy dropped.”

Through the liner notes thanking Doe and stories about Madvillainy’s creation playing out like an ever-evolving game of telephone among fans and writers online, Foster’s involvement has been legitimized while Walasia’s has been buried. Even if both are True. This represents a more dangerous aspect of folklore. If a top-down source that the folk group agrees to be authoritative tells one rendition of a legend often enough—like Stones Throw emphasizing Foster’s role—the story becomes dominant and, in some cases, weaponized against those who are excluded.

Walasia says the A&R credit she deserves would have opened innumerable doors for her career. Instead, the label listed her as “Project Consultant.”

“If you look at the credits on the album, I don’t think there is an actual A&R credit. That term, as meaningless as it is, was always one of my pet peeves and I tried to eschew it whenever possible,” says Egon. “I think Miranda got the appropriate credit, ‘consulting’ or something like that, which is what she did.”

“When I told them I needed to get an A&R credit, this is exactly what Egon said, and I quote: ‘Well, A&R credits are as rare as hen’s teeth here at Stones Throw,’” says Walasia. “I thought it was ironic and intentional that he said ‘hen’s teeth.’ Because at the end of the day...a woman made the introduction. A woman was adamant about making it happen.”

No one but MF DOOM and Madlib could have made Madvillainy, but their creation has spawned as much behind-the-scenes politics and drama as it has folkloric legend. No one predicted Madvillainy’s success. Because of the album’s impact, the individuals who contributed want to make sure that their versions of the story are represented. That their truths are told. Everyone wants to push against the dominant narrative, unless it favors them. The Truth is: Madlib wanted to work with DOOM, and DOOM liked Madlib’s music. Their similar sensibilities resulted in instant chemistry.

But Walasia is still waiting to be seen.

“It’s the biggest independent hip-hop record, still to this day. This is what I want everyone to realize, that nobody really understands. Is it because of the genius of Madlib? It is. Is it because of the genius of Dumile? It is. Is it because of the genius of Walasia? Formerly known as Miranda Jane Neidlinger? It is,” she says. “No one else has any right to claim any kind of credit for the project. For the music, the creation, none of it. That’s what I would like people to know. A woman did that.”