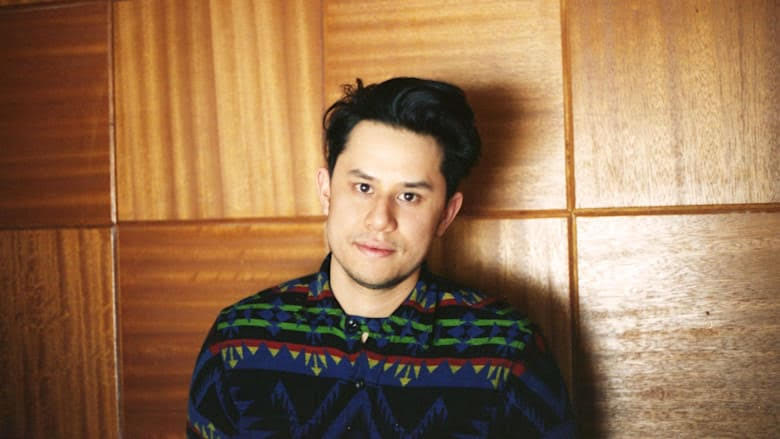

Frank Dukes has been “having a moment” for the past five years, and it’s showing no signs of stopping. He’s still your favourite artist’s favourite producer.

Dukes, whose real name is Adam Feeney, is from Toronto and is now based in Los Angeles, a fitting move for someone in such high demand. He works with names like Kanye West, Lorde, Drake, Camila Cabello, Kendrick Lamar, SZA, and Rihanna. But, it’s likely you already knew that. His touch is all over your recommended playlists on Spotify and Apple Music with tracks like “Congratulations” by Post Malone, “Call Out My Name” by The Weeknd, "0 to 100" by Drake, “Be Careful” by Cardi B—you get the idea. It's safe to say he's got a solid CV.

But beyond all the fanfare, he’s a purist who takes his craft very seriously. One who would rather wax poetic about Brian Eno’s production method than talk about being in the studio with an A-lister. Like any good producer, Dukes is an enthusiast, enamored by the idea of amassing more knowledge and exploring the infinite amount of music that exists. He’s also someone who wants to pay it forward.

In 2015, he launched the Kingsway Music Library, a resource artists and other producers can use to help mitigate some of the clearance issues that come along with sampling. It’s a depository of sounds and sonic explorations that he and other producers create for others to play with. He recalls it being a pretty radical idea at the time—to release music with the intention of it being sampled—but he points to producer Nick Brongers as someone who was doing it before him. “Nobody could figure out what he was doing [to create the sounds] and he was the first person that I knew of that was making samples for other producers to make beats out of,” said Dukes over the phone from L.A.

"To this day, that's the thing that I've chased in music: hearing something that gives me that sense of wonder." - Frank Dukes

Kingsway is modelled after '60s and '70s music libraries, which were used to access pre-made queues for television and film licensing. In this case, it’s a platform for producers to pull samples from to make beats. After encountering the music of Thomas Brenneck and the Menahan Street Band in the early 2010s, Dukes ended up sampling them at least ten times on different tracks. Their funky, jazzy, soul-rooted sound lent itself well to the hip-hop productions he was working on at the time. Following this period, he started creating pieces specifically for sampling, which grew into quite the extensive collection. Eventually, that collection became the Kingsway Music Library, which is purposely available to the public and affordable to access.

Dukes sees music libraries as the next step in dismantling barriers to access into the world of production. “Now that there are more resources that allow us to not rely so heavily on technical ability [compared to when he was coming up], a producer doesn’t necessarily need to know how to play keys at a proficient level if in their head they can make all the decisions to create something that's compelling at the end of the day, without necessarily having to have all the technical knowledge.” Not everyone learns music theory or gets classical training growing up, but programs like Fruity Loops and Ableton have made it possible for swaths more people to experiment with music production.

The next endeavour for Kingsway is a series of collaborations with other music makers, starting with a beat pack from multi-platinum Grammy-nominated producer David Bendeth and some emerging producers from Toronto, CVRE and Brandon Leger. Kingsway Collabs is all about bringing unorthodox groups together that might not necessarily link up otherwise.

In 2018, British singer Craig David released a single with American rapper Goldlink, called “Live In The Moment,” produced by the prince of Montreal, Kaytranada. One of Bendeth’s friends sent him the track and told him to listen closely—lo and behold, they’d sampled his 1981 track, “I Was There”. He loved what Kaytranada did with the track, but he wished they would have asked for a sample clearance. “I thought it was fantastic and very creative, so I was kind of disappointed that between him and his manager and the label, nobody said anything to me before releasing,” said Bendeth over the phone from New Jersey.

And there lies the problem: whose responsibility is it to clear samples? It’s the exact kind of messiness Dukes was trying to help producers avoid when he set up the Kingsway service. Bendeth reached out and settled things with the label, but then more artists started sampling his old music without clearance—including Westside Gunn on his track with "Curren$y" and Benny the Butcher on “Lucha Bros.” After he got tired of having to call around to sort things out every time he was sampled, Bendeth’s son, DJ Code Red from Toronto, suggested he make his own hip-hop pack and that he partner with Kingsway to get it done. When he reached out to the team he emphasized that he wanted to do something collaborative, “I said, ‘I kind of feel like I'm out of my league. I really want to work with young people doing it because I'm not stupid enough to think I can do this by myself. Give me your two best guys. Let me work with both of them.’”

That’s how he ended up paired with CVRE and Brandon Leger, who are part of the new school of producers out of Toronto. Coincidentally, all three of them happened to grow up in the same neighbourhood, locally nicknamed “The Peanut” (in Don Valley Village). Bendeth is known for his rock production with bands like Paramore and Bring Me The Horizon, but his early releases in the 1970s were R&B and soul records.

Dukes told them to make things that didn’t sound like anything else and the resulting pack, released last week, is a blend of Bendeth’s rock production and some chopping and screwing by the two younger producers.

In their first session, Bendeth laid down the keyboard and guitar tracks and CVRE and Leger started cutting, adding effects and plugins and metamorphosing the sound into something entirely new. After 10 days straight working together at Toronto’s ArtHaus Studios, the result was a 17-track beat pack.

The working relationship came full circle, since CVRE and Leger grew up listening to music that Bendeth produced. “One of the weirdest moments on that first day was when Brandon said, ‘I have to show you something’ and he took his shirt off and had a big tattoo on his back that was the emblem of one of the bands I produced for eight years ago, Underoath.”

Now, their pack is out in the world, waiting to be discovered and turned into something new.

Dukes posits that sampling culture in production wouldn't exist as it does now without hip-hop, paying homage to the greats that he listened to growing up—J Dilla, P Rock, RZA, and DJ Premier—whose use of sampling sounded like “magic” to a young Dukes.

“It was almost like having no concept of how they did that, how they made it sound like that. To this day, that's the thing that I've chased in music: hearing something that gives me that sense of wonder. My evolution is also really tied to the discovery of music and the entire crate-digging culture,” said Dukes.

Combing through infinite beat packs is like a new iteration of crate-digging. Instead of heading to the local record store and finding gems hidden between the stacks, producers now have the entire Internet, including music libraries, as their proverbial playground. One with a ginormous sandbox to dig through.