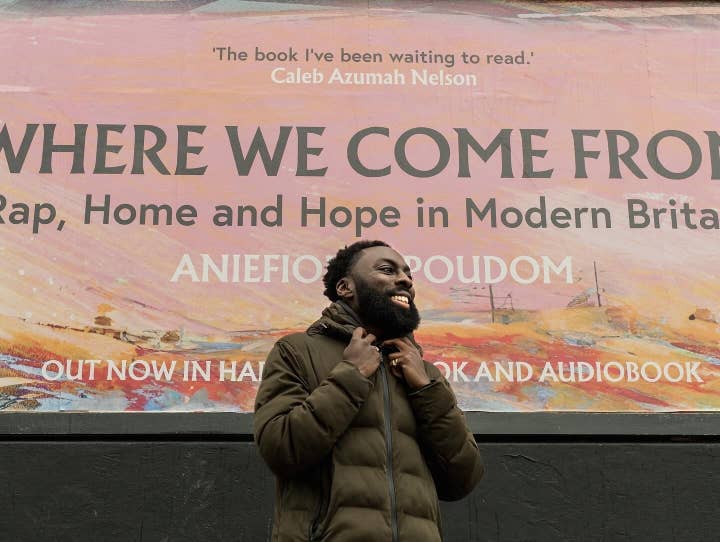

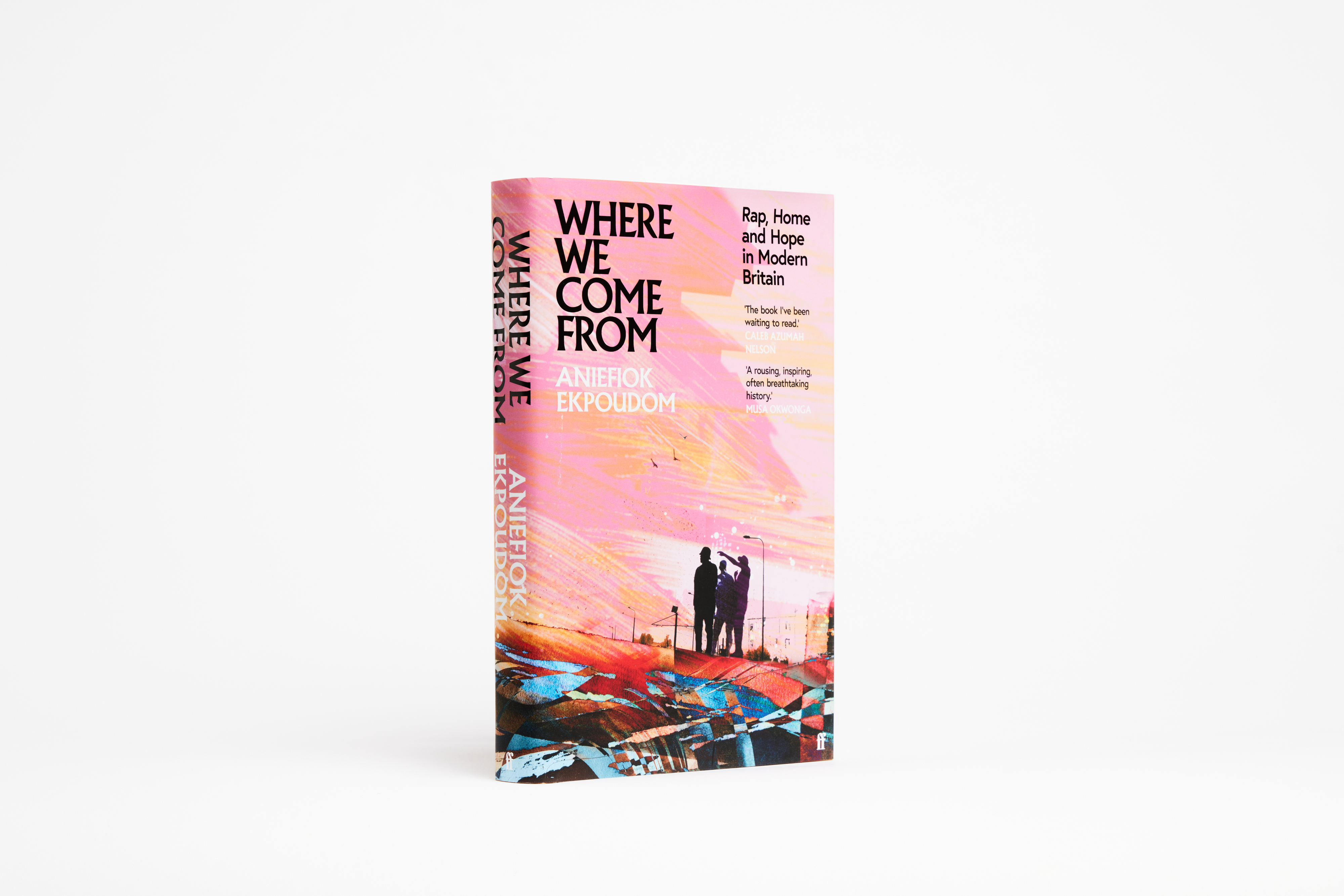

One thing that makes Aniefiok Ekpoudom’s debut book, Where We Come From: Rap, Home & Hope In Modern Britain, such a compelling read is the genuine, real-time peril that plays out across the page.

Ekpoudom—‘Neef’ to his friends—is a music journalist who has written for the likes of The Guardian, British GQ, SBTV and Complex UK, and while the focus of his book is music, he also charts the decades-long erosion of communities, through post-industrial rot and the chipping away at public and youth services, therefore leading to a country full of disaffected youth with pent-up frustrations and only their own, self-made outlets through which to vent them.

A lot of the stories Neef documents from the rap and grime scenes of the past two decades are born from a society on flux. Whether it’s the late rapper Cadet struggling to escape an unfulfilling job while he watches his peers achieve global success, or the rap-rock outfit Astroid Boys battling to escape a town bereft of job prospects, there’s an urgency to their struggles because they need their gambles to pay off; there really is no backup plan, no safety net.

But there’s another layer to that urgency when you consider the landscape of music journalism (read: storytelling) in 2024. Vice, the once media behemoth that just five years ago was valued at $5.7 billion, continues its death spiral with round after round of layoffs. Meanwhile, Condé Nast—which owns multiple outlets, including The New Yorker, Vogue, Vanity Fair, GQ and Pitchfork—has been through its own round of layoffs. Once seemingly invincible powerhouse media brands are crumbling all around. It’s not just the jobs that are disappearing, making music journalism an increasingly difficult career to pursue, the stories published on these platforms are also under threat, liable to completely disappear should that site be shut down.

With that backdrop in mind, it makes Neef’s storytelling all the more crucial. He’s not just telling these stories because he happens to have a style of narrative that lends itself better to the longer form, it’s because—despite what we were told at the advent of the digital age—the online sphere is not actually that permanent. He’s putting these stories onto paper so that they don’t go the same way of so many grime and rap mp3s from the blog era: into oblivion.

In a packed West London cafe, we sat down with Neef to talk about these stories and if there can be any hope at all for the future.

“History not being archived in the right way, or by the right people, is a very dangerous thing.”

COMPLEX: When did you start working on this book? I ask that as the most recent event in it seemed to be around 2021.

Neef: I started the interviews around 2017 or so. I think the first interview I did was with Despa Robinson and then, I think the year before, I’d gone to Manchester to interview Bugzy Malone for Vice. That’s when the stems of the book started to come to life, around 2017, and then the last one was in 2022, so it took about five years in total.

How did you decide on the parameters of the story? Pretty much all of the areas and people you featured could have had books of their own.

So, as much as it is a social history of Britain, I wanted the book to be a documentation of modern Britain as well. I knew I would have to bring in different regions all across the country; it couldn’t just be South London. So, it was like: “Okay, I need to go to the Midlands, and then I need to leave England.” I started going to Wales, and I guess as I started to meet people, especially Phil [Traxx from Astroid Boys], it all started to come together. I had known Despa from before, and had known a bit of his story and we were already cool. I was just looking for stories that were emotionally resonant, but that also said a lot about the music itself. And also how transformative the music can be, how transformative rap can be in someone’s life away from the idea of record sales and commercial success. What does success in music actually look like in someone’s personal life? That was the idea and instruction. It took a long time because you have these different regions; that’s when I started to really try and separate the beats almost by decade of what’s going on, so it flows from the Windrush through to garage then So Solid through to rap.

So that planning process where you put the structure together, at what point did that play into it? Was that early on or was that afterwards when you’re assembling and editing?

It was after because I wrote it section by section. I wrote the full South Wales section first. I wrote that all out, then I wrote the full West Midlands section. The South London one was the last one I wrote. So when I wrote the full South Wales and West Midlands sections, I could then see what the similarities were and certain themes started to come out, but also a timeline.

When you’re telling stories that stretch back years, there are some you were present for and others that are secondhand, but they’re always so vivid. Did you have to sit down with someone and brainstorm to draw it out of you?

Yeah. Take Despa, for example: we’re talking about what life was like growing up in Walsall, in a post-industrial West Midlands coal town. He gave me a lot of the building blocks so I could go off and do my own research about these places. I already had the personal narrative and then I was able to add the social element of it by going to research the areas myself. That was a big part of it. For example, if I’d been somewhere with someone in Cardiff, or I’d been talking to Pa Salieu… I interviewed Pa Salieu in London every single time, but I went to where he’s from—Hillfield, in Coventry—four or five times on my own, just to see the place for myself and be able to capture that in words.

There has to be a lot on the cutting room floor. Are there any stories that you wish you could have included?

There were so many stories from the wider scenes in Birmingham that I would have loved to have covered. Trilla and bassline could have had full chapters. That’s a subject that still fascinates me: that idea of this subculture of music which just existed in essentially the middle and Northern half of the country, and didn’t really touch London but was still so influential. That’s a whole chapter in itself, but I only got to capture it for about two paragraphs. There was another guy, Major, from Birmingham, who passed away recently, but he ran a big music studio that MCs, drill artists, reggae artists, all these different generations all came through. He had a fascinating story. I only got to put a little bit of his story in there. I think that’s the hard thing for the book: knowing when to stop, essentially. Knowing that as much as I love this, it would detract from the actual book.

“I think music and culture journalism will always exist. The places may shrink and it may not be in as many places as before, but I think there will always still be a hunger and a need for it.”

How did you decide on each location?

There was definitely a conscious decision to go to places people didn’t expect. A few people have asked me, “Why didn’t you go to East London?” But I feel like that story has been told so well in so many different formats. You’ve got DJ Target’s book, Dan Hancock’s book, Joy White’s book, so I was trying to go to places where the story hasn’t been as documented. Obviously, Birmingham has a long-established music scene, so that was a bit easier to access in terms of knowing who to speak to. Wales was a lot more difficult, though. I’d only heard of Astroid Boys and they were the first group that showed me a side of Wales I wasn’t familiar with. I guess the natural story of Wales is very rural: green land, farms, stuff like that. Then I speak to them and I start to see a deeper story that piqued my interest. I was definitely surprised a lot going to Wales; the most surprising thing was probably hearing about the history of the Black communities there. I think I’d always assumed contemporary history of Black people in the UK started with the Windrush Generation. It was only when I got to Wales and discovered the history of Cardiff and the docks, and that some of the oldest Black communities are there. Going to Cardiff and hearing about these families that have been there for literally 100 years... People were showing me wedding photos in 1902 with Somali people, Nigerian people, Caribbean people. I didn’t know that history existed.

Do you see there ever being, like, a sequel, where you explore other regions?

I never intended on writing a second one, but quite a few people have asked me. I can’t see it, but I definitely want to explore some of those stories in different formats—whether it’s long-read pieces or documentaries, or podcasts.

The post-industrial element seems to crop up in towns and cities with thriving rap scenes. Even though they’re completely different industries and completely different stories, did you discover any other surprising common themes?

Yeah, the post-industrial factor was probably the biggest. Immigration was another. My parents are immigrants, but they only came to this country in the ‘80s, so I don’t have that direct connection between music and those historical factors. It’s always been abstract, in that sense. But then you go to these places and you realise—actually, no: post-World War II, the post-industrial age of Britain, it’s all really shaped them. A lot of the areas were shaped by that, from factories closing down in the West Midlands and the docks in Cardiff. A lot of those places are the way they are now because of the high unemployment and things like that. So some of that was quite surprising, but it was quite interesting to see just how connected the music is to both contemporary British history and events we think of as being in the distant past.

With a story like the late Cadet’s, presumably it took quite a while to build up that level of trust. How did that go? Did you have to spend a lot more time with him before certain stories came out?

I think it ranged. There’s definitely a big element of trust there. I think my journalism background helped because I was able to show people this is how I like to tell stories. It’s about looking at the humanity within the music, within the people. The amount of time I spent with people helped build up that trust as well. Some interviews, I’d meet an artist for the first time and—bang!—we’d get straight into a really personal, really deep conversation, but some have taken longer to get to that point. Generally speaking, it was actually quite beautiful to hear people—especially a lot of men and young men—feeling comfortable enough to to be able speak about their life experiences and some of the traumas they’ve gone through and how they’ve either overcome them or tried to overcome them or still have been shaped by them. That was definitely, like, one of the most emotional aspects.

Reading the stuff about the Cadet concert and the memorial, that was really moving. I knew the story and it wasn’t a surprise to me, but still, it really is a real gut-punch.

Yeah, definitely. I feel like that was probably the hardest story to report on because it was dealing with grief and speaking to a lot of people about grief. The story is so sad, but it was nice to see how much his music had impacted people. I spoke to his mum. I spoke to his sister. I spoke to a lot of his close, childhood friends, people he worked with. A lot of detailed effort went into making sure I was chatting to the right people and how they’ve coped with things over the years.

There does seem to be a lot of tragedy in the book—not just on a personal level, but on a community level, with youth clubs, gentrification and everything like that. But there is a little bit of hope with the new gen of artists, like Pa Salieu and Luke RV. How did you feel coming away from everything? Hopeful? Exhausted?

It’s so interesting because, with the three regions, I kept thinking: “What are the building blocks of the music?” I knew youth clubs were a big building block of grime and UK rap. Pirate radio, of course, was another massive building block. Then there were the DVDs, another massive element. So DVDs became the South London section, the youth clubs were the South Wales section, and pirate radio was in the West Midlands section. That’s how I structured it. When you get to the end of it, you really see the fragility and tragedy in the regions. I’ll never forget one of the youth workers telling me that with the stroke of a pen, youth budgets got cut by nearly 80%. Cardiff went from having a thriving youth service, with a youth club in every corner of the city, to two or three in the space of the day. That was heartbreaking to hear.

One thing I wanted to ask, especially with all the awards shows we’ve had recently, as rap dominates the charts, soundtracks adverts and so on, do you think it’s been accepted in the mainstream yet?

That’s interesting. I don’t think so. I think the music is accepted and I think it’s only accepted because it became undeniable. That grime wave in 2014, 2015, and the rap wave that followed, it was undeniable. You couldn’t not accept it. It was everywhere! Stormzy, of course, was everywhere. Skepta literally changed culture in the UK. And then, obviously, Dave, Giggs, all of these people made it truly undeniable to a point where it had to be accepted. But I don’t think the artistry of it is accepted as much because Potter Payper, for example, is probably one of the best writers in the UK—period. But I don’t think that element is accepted and the artistry isn’t accepted in the same way we’d accept a new novel. The community and culture aspect that the music comes from is definitely not accepted in the same way. People talk about how great the music is, but then when issues in the community arise—whether it be police brutality, racism—we’re still having the same conversations we were having 30, 40 years ago.

Obviously, you got your start in music journalism but, as we’re seeing it slowly crumble around us, what do you think the future holds for this kind of longform, narrative storytelling? Because you can’t go straight to publishing. How do you think they’re going to be recorded?

I think that’s the scariest thing, right? Because the worst case scenario is they don’t get recorded. History not being archived in the right way, or by the right people, is a very dangerous thing. I’ve been seeing the lean into the Substack and I’ve subscribed to a few people’s Substacks, and I think that’s a very interesting space because I guess it gives people the autonomy to tell stories on their own terms. Of course, you don’t get the infrastructure that you do with an actual magazine or a publication or a newspaper, but it’s been interesting to see people take ownership of how they tell stories. I’ve enjoyed that. I think music and culture journalism will always exist. The places may shrink and it may not be in as many places as before, but I think there will always still be a hunger and a need for it, but the formats will likely change.

We’ll probably start to see a lot more documentaries and a lot more TV shows. We’ve started to see a lot more podcasts and narrative podcasts already, so I think it is happening in different formats. When I was growing up, journalism and books were a very prominent thing of that time period so they mean a lot to me. Maybe if you’re an 18-year-old and you’re thinking about telling stories, maybe a book isn’t the first place your mind goes to. Maybe it goes to a podcast or even YouTube and those kinds of things. I think it will also evolve as creativity evolves for the next generation.

Do you think we’ll see a return of the blogging era?

The blogging era—what a time! I think so, maybe. When I see Substack and stuff like that, it feels a bit more in-line with what the blogging era was: people just talking about what they want to talk about, sometimes without even a remit. It does remind me of that grime blog era. I remember growing up reading JP’s blog, Hyperfrank’s blog, Tinie Tempah and Tinchy Stryder—they had blogs as well. I read these blogs incessantly! I feel like we’re starting to see people own the blogging style a little bit more, which has been interesting to see. You’re also seeing quite prominent writers embracing that format. I was reading about Bret Easton Ellis recently; he wrote a book on Substack before it was ever a thing... There’s weird things happening in that space right now.

You’ve been taking the book on the road with launch events, Q&As, and so on. Meeting all these people who have read the book, have there been any takeaways that have surprised you that people have told you about?

At the launch at the South Bank, Candice Carty-Williams was telling me that she was drawn to the writing because of hearing a lot of young men really express themselves and be quite open in ways that she hadn’t seen before. I hadn’t necessarily thought about it in that sense. I knew these were really personal stories, but I hadn’t thought about it in the sense of men breaking through personal barriers to express themselves and talk about some of the things that we’ve been through—whether it’s traumatic experiences or fears that we have, hopes that we have, aspirations that we have. That definitely surprised me because I just never considered it as I was putting the book together. I’m really glad it’s having that impact.

Where We Come From: Rap, Home & Hope In Modern Britain is out right now.