Last September, at the Forum in Inglewood, Calif., the slumbering Wu-Tang Clan rose once again. Fans sporting black T-shirts adorned with faded gold lamé Wu logos packed the house to watch men in their mid to late 40s perform classics from the ’90s. Method Man bounced around on stage and RZA took swigs from a bottle of Grey Goose, but Ghostface Killah showed his age, at one point waddling over to the corner to greet an old friend and tell him that he was exhausted. That old friend was Steve Rifkind, the man who signed Wu-Tang to his company Loud Records in 1992 and someone who can offhandedly recall the time Ghost traveled to Africa in search of a cure for diabetes only to end up catching malaria.

Backstage, Raekwon helped usher Rifkind through security. Masta Killa greeted him with a pound and a hug and jokingly called him “Mr. Rifkind”—a formality he knows his former boss hates. Someone in Wu’s entourage exclaimed, “You looking like ’97! This guy is looking great!” referring to Rifkind’s recent loss of 50 pounds following a health scare. Wu’s manager, Mitchell “Divine” Diggs, and the RZA chopped it up with Rifkind’s collegian son, whom they remember from back when he was a shy little boy.

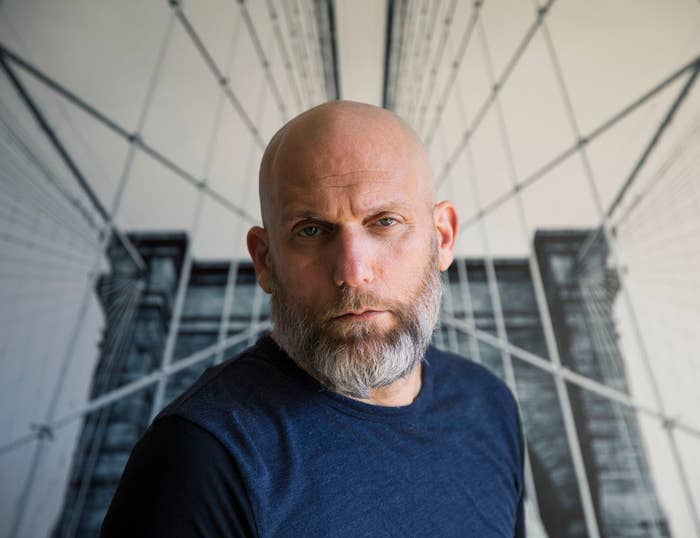

Rifkind, 52, is arguably best known for signing Wu, but at Loud he also shepherded careers for Mobb Deep, Big Pun, Tha Alkaholiks, Three 6 Mafia, Xzibit, Twista, dead prez, and others. After selling Loud to Sony in June 1999 and leaving the company in 2002, he started SRC Records, which broke artists like David Banner, Melanie Fiona, Asher Roth, and, most notably, Akon. A master of rap promotion, Rifkind’s name is also synonymous with “street teams,” the crews that spread the word about the majority of rap releases in the ’90s. Rifkind left SRC in 2012 because of label politics, but in July 2013 he found a new venture, teaming up with Russell Simmons and film director/producer Brian Robbins for All Def Digital and its offshoot, All Def Music. He’s not as iconic as Simmons, or as infamous as Suge Knight, and he doesn’t maintain the celebrity of executives-turned-rappers like Puffy, Birdman, or Master P, but Rifkind is one of hip-hop’s greatest executives, one who’s consistently found ways to win in the always-evolving music industry.

The music business is in Rifkind’s blood. His father, Jules Rifkind, and uncle Roy Rifkind ran R&B label Spring Records in the ’70s when it was home to artists like Millie Jackson and the FatBack Band. His dad helped arrange James Brown’s first major label deal and scored Elvis Presley and Barbra Streisand their first shows in Las Vegas. Millie Jackson, the Fatback Band, and James Brown even attended Rifkind’s bar mitzvah in his hometown of Merrick, Long Island, in March 1975.

Despite suffering from dyslexia and nearly getting expelled for fighting with the principal, Rifkind graduated from high school, but after only three days at Hofstra University he dropped out to work for his dad at Spring. Still a teenager in 1979, he helped promote the FatBack Band’s “King Tim III (Personality Jock)”—one of the first hip-hop records ever, predating “Rapper’s Delight.” Rifkind eventually became the vice president of promotion at Spring. (DJ Scott La Rock, of Boogie Down Productions fame, was his intern.) When he was 24, Rifkind moved to L.A. to manage New Edition for a year before he started doing promotions for indie label Delicious Vinyl. In 1987, he went into business for himself and started the Steve Rifkind Company, promoting records for acts like Boogie Down Productions and Leaders of the New School.

By the early ’90s, the Steve Rifkind Company was billing hundreds of thousands of dollars doing retail, radio, and video promotions for indies like Delicious as well as major labels like RCA. Along the way, Rifkind discovered “street promotion,” which bypassed all three forms and focused on things like word of mouth, getting music in the hands of urban “tastemakers,” and plastering stickers and posters for upcoming albums anywhere rap fans might gather. Thanks to his upbringing, he understood both hip-hop and the music industry. Rifkind began growing a national network of street teams but eventually realized he was better off starting his own label rather than solely promoting acts for others. He founded Loud in 1992 with his childhood friend Rich Isaacson but kept SRC’s lucrative street promotions teams open for business. “Any rap record from 1989 to 1999, besides [ones on] Death Row, we did promotions for it,” says Rifkind. “We had our hand in everything.”

“We built Loud Records through SRC, Steve’s original idea of street marketing,” explains Isaacson. “Loud Records already had a built-in marketing and promotion apparatus through SRC. When we got a tiny bit of funding from BMG, we were able to sign something cheaply and promote it.”

Loud was a family affair. Jonathan Rifkind, one of Steve’s two brothers, served as the label’s executive vice president; his mother was their travel agent; his father even did some independent radio promotion for them. The first acts Rifkind signed to Loud were Twista and Tha Alkaholiks, but for him it always comes back to Wu-Tang. In 1992, the Wu came swarming out of Shaolin with “Protect Ya Neck,” a five-minute lyrical beatdown armed with karate chops on the dusty, lo-fi beat. Rifkind left messages on RZA’s answering machine for weeks trying to get in touch with them. On his 31st birthday, he got the best birthday present ever when RZA showed up to his office.

Rifkind’s experience managing New Edition had taught him that the group would always be bigger than the solo artist. So, he created what was then an innovative contract that signed the Wu to Loud but allowed each individual group member to sign separate solo deals so long as Loud had the first right of refusal. It didn’t matter either way to Rifkind: The other labels would still pay SRC to market solo Wu records.

“What made [the Wu] different from everyone else was that they had RZA, and he was so much smarter than everybody else,” says Rifkind. “RZA would come every night at 6 o’clock with a yellow legal pad with 27 lines, with 27 things to do. If it was 85 lines, I would say yes to 80 of them. Then one day he was like, ‘Why are you saying yes to all of them? Are you scared?’ I’m looking at him like, ‘Why would I be scared? Everything that you’re saying makes sense.’”

According to Isaacson, Loud went from a $3,000 initial investment in 1992 to over $100 million in sales internationally in 1999. Best of all, Loud was, as Rifkind says, “a keep-it-real label” that scored gold and platinum plaques for hardcore acts like Big Pun, Raekwon, and Mobb Deep without conforming to radio. Meanwhile, by the late ’90s, SRC was attracting non-music clients like Nike, Tommy Hilfiger, and even the U.S. Army. Corporate America was taking notice, but Loud’s NY offices—first located in Union Square and later moved to 205 Lexington Ave. in May 1996—were anything but corporate. Combativeness was commonplace at Loud’s offices.

“Arguments would erupt in the middle of the hallway because we had so much passion,” says Liz Hausle, All Def Digital’s executive vice president of marketing, who got a job at Loud in 1994 as the label’s first product manager. “It wasn’t, ‘That’s not professional. Don’t have an argument.’ Everybody would stand around. It was like we’re watching a verbal boxing match, fighting for what we believed in. You had to have the balls to physically stand up to each other. It ended in respect for one another. After we’d argue we’d all be out having a drink together, laughing our asses off.”

The wild times went far beyond arguments between staffers. On one occasion, Raekwon reportedly popped up and ordered strippers to the office. Rifkind claims he once caught a woman running an escort service out of the joint. One day a man showed up with an empty stroller and, when everyone was off in meetings, used it to steal the office computers. Rifkind wasn’t always at the office, either. He went on bus tours throughout the country, exploring different markets, getting a feel for the streets, and discovering Southern acts like Three 6 Mafia along the way.

“I wasn’t into drugs, I was into pussy,” said Rifkind, who claims the office had orgies every Friday. “Loud got me laid.”

Despite the extracurricular antics, it wasn’t all fooling around.

“Steve told us to use the departments to our advantage,” says Prodigy, one half of Mobb Deep, which released classics like The Infamous and Hell on Earth through Loud. “We’d go up to the office, smoke weed, and pick the brains of all the employees to see how we could make the albums sell better, make the videos better, make the promotions better. Steve told me, ‘Build your own studio and charge it to Loud, so the money will go in your pocket. That’s how you get money.’ It was my schooling about the business. Everything that I know and try to do now, I learned from being on Loud.”

After experiencing success and selling Loud to Sony in June 1999, things didn’t go well for Rifkind. Once the press started reporting about Loud’s success, his wealth attracted shakedowns and he received death threats. He also began suffering panic attacks. With all that stress, he squabbled frequently with his brother Jonathan and partner Isaacson. Adjustment to corporate culture—which included his staff ballooning from a familial 30 to 200, and one employee in particular suddenly addressing him as “Mr. Rifkind”—overwhelmed him.

Rifkind considers himself more of a promotions man than an A&R guy, but part of what made Loud so successful early on was his instinct with artists. He signed Mobb Deep because of their music, but also because their tough-as-nails, zero-fucks-given demeanor impressed him. (They set off the fire alarms smoking weed in the Loud bathroom.) Rifkind offered Big Pun a deal without ever hearing any of his music because he was impressed that Matteo “Matty C” Capoluongo—an A&R who didn’t bother to pick up a six-figure royalty check for weeks—unexpectedly showed up at the 10 a.m. meeting just to meet Pun. Once Sony bought Loud, Rifkind being a promotions man with an eye for talent wasn’t enough.

“Steve is not the kind of guy who is going to sit in an A&R administration meeting and talk about whether we’re over budget on samples on the Beatnuts record,” says Isaacson, whom Rifkind tasked with those kinds of duties. “When you start a business and it grows, then you have a responsibility to all those other people and the artists. He walked around the office like, ‘Who are all these people?’ Steve got really frustrated, and we used to fight because he hated that the company was like that. But if we’re going to have 30 artists then you have to manage this. Managing the staff, managing artists and their expectations, managing corporate expectations, and trying to make sure me and Steve are on the same page, it was not easy. We got too big too fast. That was probably our demise.”

The size of the roster and staff wasn’t the only issue. Despite doing $100 million in billings, Loud didn’t turn a profit in 2000 because of its massive overhead. Toward the end of the Clinton administration, both the music business and the economy at large were booming. The grit and grind of the early days had turned into overblown excess. Guys like Gabriel “Gaby” Acevedo, who was Loud’s New York radio rep, says he spent $20,000 to $30,000 a month on his corporate card schmoozing with the powers that be at Hot 97 and WBLS.

“I’d go to the club and be like, ‘Lemme get four bottles of Moet!’” says Acevedo, who currently manages French Montana. “What we were doing before, you could never do that again. That whole corporate card thing ain’t what it used to be. You can’t even buy someone a hot dog on the corner these days.”

“As you grow you have to start making numbers to justify everybody’s salaries, the offices, and the overhead,” explains Isaacson. “All of a sudden you look down and go, ‘Holy shit! Look how big our overhead is! In order for us to keep this overhead this high you have to have this much revenue.’ Then they expect you to do it every year. Then something doesn’t happen and you get pressure. Sony goes, ‘You guys are spending too much money. You can’t go for a fourth single when the second single wasn’t successful.’ We didn’t want to hear that. Nobody does that now; it’s a different industry. No one would go four singles deep on Sadat X.”

Artists took notice. “When he sold the company to Sony, Steve didn’t make the decisions anymore,” says Prodigy, who released Mobb Deep’s last album on Loud, Infamy, in 2001. “It was some people at Sony who probably didn’t give a fuck about Mobb Deep because we didn’t sell enough records. Mobb Deep made hardcore hip-hop, and we was going to do our numbers, but it’s not so much about first-week sales and ‘Did you go platinum?’ We felt like goldfish in an ocean with sharks and whales. So we knew right away it was time to go because Steve had nothing to do with it anymore. The writing was on the wall.”

All of the changes and stress only exacerbated Rifkind’s famous temper. (He once threw a chair at RCA’s chief lawyer, Carol Fenelon, because the company wouldn’t put up the money for Loud to sign Raekwon as a solo artist and release Only Built 4 Cuban Linx.... Security escorted him out.)

“One time I came to the office and Steve had a bandage on his hand,” remembers Prodigy. “I was like, ‘What the fuck happened to your hand?’ Steve was like, ‘I went to this car lot to buy a car, I asked the dude, ‘How much is the car?’ and he tried to brush me off like I couldn't afford it. We got in each other’s face, I ended up swinging on him.’ He beat some dude up in the car lot and the dude bit his hand or some shit. I’m like, ‘What the fuck are you doing? You got a million-dollar company and you fighting in the car lot? You bugging, yo.’”

When Rifkind traveled to Hawaii in February 2000, all these troubles weighed heavy on his mind. While staying at the Four Seasons, he decided that all the money in the world wasn’t worth the aggravation and sat down and wrote a letter of resignation to Sony Music’s chairman, Tommy Mottola.

Later that day, two Samoans came running up to him while he was in the middle of a heated tennis match to tell him that he had an emergency on the mainland. Rifkind was used to late calls and emergency situations. They were typical in his 24/7 work world. He once got a call at 1:30 a.m. because someone in Big Pun’s entourage had accidentally broken his new head of promotions’ eye socket. Rifkind rushed to his phone, concerned something might have happened to one of his parents. Isaacson was on the line and told him that Pun was in a coma. Pun died shortly thereafter, of a heart attack and respiratory failure.

Before hopping on a plane to the mainland, Rifkind wrote a check to Pun’s family and tore up his letter to Mottola. But it didn’t matter by then: Loud was suffering from myriad problems. He ultimately left the company in 2002.

On Christmas Eve 2013, Steve Rifkind saved his own life. He was playing basketball with his sons when he felt a pain in his back. Fearing doctors provided nothing but bad news, he hadn’t seen a real one in 30 years, instead getting scripts for painkillers from shady sources. But he sensed something was wrong.

“Call 911,” he told his ex-wife Nicole. (They separated in 2007 but remain cordial.) “Something’s the matter.”

“Take a Xanax, take a shower, go to sleep,” she told him.

He popped a bar and took a shower, but also called 911. The ambulance was there when he stepped out of the shower and felt a strain in his left arm. By the time he got to the hospital, he’d had a heart attack. He flatlined three times and each time was shocked back to life. He woke up in the hospital with a tube down his throat and a stent through his groin.

“When I got word, I called him,” says Scooter Braun, Justin Bieber’s manager. Rifkind had offered Braun a job running his new SRC label mere hours after meeting him in 2008, but Braun was more interested in getting a deal for his artist Asher Roth. “He had been in the hospital for five days, and said, ‘I worked so hard my whole life, I haven’t taken care of myself enough. I’m getting a second chance. All I’ve been thinking about is how hard you work. You need to change your sleep habits and take care of yourself because I don’t want this to happen to you.’ He was in a hospital bed while I’m on vacation and he was more worried about me than he was about himself.”

Rifkind needed similar words of inspiration in the days after he’d left Loud. He was miserable and refused to get out of bed, feeling he’d let his Loud family down by succumbing to corporate politics. His teary-eyed wife called reinforcements. Rifkind’s father showed up at his house with Heavy D, a close friend with whom Rifkind regularly consulted on ideas and artist signings (he was the first person Rifkind played Akon for). The heavyset rapper playfully punched him in the face.

“Hev goes, ‘Get your ass out of bed. This is the best day of your life. Let’s go for lunch,’” says Rifkind, tears in his eyes, remembering his friend who passed away in late 2011. “They took me to lunch and Hev gave me the most beautiful speech that anybody can give somebody. He was like, ‘This should be the happiest day of your life. You have three beautiful kids, you’re married, and you got your health. What the fuck are you depressed about? You built one of the biggest and best record companies in the world. The whole world loves you.’ That’s what motivated me to start SRC.”

Rifkind imagined the label being “Loud on steroids,” but it didn’t compare. Loud was defined by grittiness, whereas SRC’s roster was radio-oriented. Melanie Fiona spent nine weeks at No. 1 on the R&B charts with “It Kills Me” and won two 2012 Grammys for her guest vocals on Cee-Lo’s “Fool For You.” Asher Roth was one of the first rappers to turn Internet buzz into a Top 40 hit with “I Love College.” Terror Squad became Rifkind’s first act to score a No. 1 hit with “Lean Back.” But all of them pale in comparison to his most successful act ever, Akon, whom Rifkind discovered after a friend played him a song called “Trouble” while he was in L.A. Rifkind was supposed to fly to New York that night. Instead he flew to Atlanta and signed Akon the next day. After hitting the scene with street anthem “Locked Up,” Akon went on to become an international pop star with 27 Top 40 hits to his name. Between “Locked Up” and “Lean Back,” SRC essentially owned the summer of 2004.

By all means, SRC was another success for Rifkind, as he once again took a small initial investment (his reputation for spending too much money at Loud preceded him) and turned it into a profitable company. Once again, he did good by his people. Acevedo declined a series of job offers after Loud shut down and stood by Rifkind, who made him president of SRC and a millionaire. But once again, corporate politics got the best of Rifkind. This time, Rifkind fought SRC’s parent company, Universal, in the midst of a tumultuous 2000s that saw music industry profits fall off a cliff.

“There was this guy by the name of Ivan Gavin who single-handedly ruined Universal East Coast,” says Rifkind. “He was just a numbers guy and he had no feel. All he was about was cutback, cutback, cutback. At the end of the day, there was nobody that sold more records than me in that building—including Def Jam.”

In 2012, Rifkind left SRC. He spent the next year laying low, but now he’s stepping into his new venture, ADD, where he’ll try to promote and develop artists through YouTube. Following his heart attack, he started working out and stopped eating salt and drinking (hence his leaner frame). He’s also trying to change his work habits so he doesn’t get stressed out with busywork. Even his legendary temper seems to be in check. Despite all the positive life changes, the past year was still trying for Rifkind, whose father passed away on Feb. 9, 2014.

After finding success in both the ’90s and 2000s, treating his companies like family, Rifkind was ultimately undermined by corporate interests. Since ADD launched in July 2013, the company hasn’t broken any stars that seem poised to become the next Wu-Tang or Akon. At least, not yet. But only a fool bets against Rifkind, who’s turned small investments into multi-million dollar companies twice before. That’s the kind of record that promotes itself.